Fine and Dandy

‘Simplicity is the Death of the Soul’ – Norman Hartnell

And so it was I duly arrived at this monumental metropole, home to monarchs, the financial crucible of the City and the fulcrum of Parliament in the wilting days of flower power. This wasn’t really where I wanted to swing but would prove a convenient base from which to make my next move. So much so, that I too would declare ‘England Made Me’.

As the darling buds of May began to shoot, pointing toward the warm summer season ahead, I tested the waters. I entered first into the shallow end breathing an atmosphere that simply reeks with class. I wouldn’t reject outright the lifestyles and pursuits of the ruling genteel establishment. They would just become less and less relevant. But not before a taste of glitz where fashion sits.

In need of a wardrobe for working in schools, this man of meagre means scrubbed up, primping and preening himself swish, mussing up his white tie. All so as to check out, attired in his one and only suit, the high-end house of Norman Hartnell located in Burton Street in the heart of London’s swank Mayfair. Stoking its ventricles, keeping the world safe for cuff links and cravats was an old chum of Cecil Beaton’s, Mr Hartnell, designer and couturier by royal appointment. He had told me he would very much like to visit my beautiful country of Australia.

The pursuit of beauty was something we both shared. Sir Norman, supreme arbiter of taste, designed the most elaborate regalia which he hung – along with any expense. Dressmaker to Queen Elizabeth, the garment he made for her wedding contained 10,000 seed pearls and many thousands of white crystal beads.

What a waste, you might think. It was only worn once. But surely Sir Norman tried it on himself a few times.

His decorated gowns became a byword for lavishness and intricacy, owing much to theatrical costumery.

His strapless gowns were regarded as a compromise between the law of modesty and the law of gravity.

However with respect to female vestments, my interest has been more one of divestment rather investment. In general my tastes are less frilly and my soul has remained intact.

His palatial house exuded an aura of splendour and finery. I watched on intently the ingress of the visitors. Young girls of marriageable age coming out into society as part of the social season were chaperoned inside. Debonair dickybowed beau brummels and gushing toffs – ‘debs delights’ – with billowing scarves ponced up the stairs. Two bright old fey things dressed to the nines bumped into each other, starting up the stairs at the same time, swaying from side to side. ‘After you Claude,’ said one, doffing his hat.

‘No after you, Cecil. Age before beauty.’

‘No, pearls before swine.’

The age of chivalry was not dead.

They would not live enough to come out officially.

Cecil was none other than the famous set designer himself. Having shaved at 12.45pm as was his rule to look fresher than other gentlemen, he was wearing a a broad-brimmed hat and widely knotted tie.

His white suit was a size-too-small. He had his clothes made that way to flatter his slim figure.

‘Narrow shoulder, flared gently at the bottom. Saint Laurent definitely,’ he said to his companion, referring to the dress of some woman ahead of them.

With his natural affinity for fashion, he could spot by a glance at the cut of a shoulder which Paris fashion house a garment had come from.

After flashing my calling card, cutting a fine figure, I followed them, sauntering up the graceful staircase, paralleled with mirrors, to the jinga-linga jangle of baubles, beads and bangles and the clicking of high heels. Ushered inside, I assumed my position with aplomb in the sumptuous salon, my eyes straying around me. An array of gilt mirrors and two giant crystal chandeliers created an air of tranquillity.

In this chosen circle of high estate, everybody who should have been was there, including yours truly. Pretentious? Moi?!

They came to show off, to see and be seen. The sons and daughters of those drawn by Cecil Beaton a generation earlier.

Seated on their plush gilt encrusted chairs, la di da uppercrusted simpering society hostesses, fawning puffed up men about town, preening popinjays, louche lisping lounge lizards, gleaming oh so dainty debutantes, their hair immaculately coiffured, and hoity toity thoroughbred royalty, dripping in pearls and diamonds, formed an ornate rococo tableau vivant as if in one of the paintings of the ‘fetes galantes’ by Watteau, from which Sir Norman, theatrical production designer at Cambridge, had drawn inspiration.

Assuming an air of much consequence, luxuriating in the very proper ways and manners of a more regal era this niminy-piminy ‘who’s who’ of London’s social pages, straight out of ‘Tatler’, inspected endless raiments of haute couture confections floating elegantly by.

Upper lips became unstiffened in this rarefied glittering bon ton of fashion, gossip, artifice and illicit romance lubricated by a constant flow of champagne and cocktails. Fizz, fizz, fizz. Pop! Pop! Pop! To the sound of crushed ice clinking against glass, bow-tied, liveried waiters served guests at a long table draped in linen. A treat for the effete. Eschewing the sugar bowl for lively intimate conversation, the ladies and gentlemen proved the truth of 18th-century author Henry Fielding‘s quip that ‘love and scandal are the best sweeteners of tea’.

Waited on hand and foot, seeing myself as wellborn and bred as any, I succumbed to unapologetic pampering, tucking into the dainty delectable hors d’oeuvres, stuffing myself to the gizzard with smoked salmon. I knew it wasn’t done in such titled circles, but what the heck – I done it.

Presiding over procedures was Sir Norman, representing the quintessential gentleman, exquisitely turned out, all polished sureness, hovering around seeing that everything was up to snuff and a pinch above it. Nothing, whether a permanent or passing feature, escaped his eagle eyed glance – be it the careless placing of a chair, or the slightly crooked angle at which a painting was hung. On this occasion one of the Renoirs with which he associated ‘a touch of chi-chi.’

Mr. Hartnell was politely pleased to be introduced to me: ‘Topping display! ’I told him, This is a nice little place you’ve got here, Sir Norman.’

‘It’s a humble house, a roof over our heads. It keeps the raindrops from falling on them’

I presented a small gift to him, a token of my gratitude for showing me a glimpse of this dying breed – London’s tribe of cosseted silk stockings and foppish hangers on. The book showed how the early artists in NSW gradually adapted to accepting the new landscapes and not seeing it as they would like to – full of English gardens and familiar animals.’

‘Oh my giddy aunt!’ Sir Norman exclaimed, ‘what a great way to connect with Australia’s beautiful environment and captivating animals. Thank you so much.’

I would have liked to have had the opportunity to show Sir Norman my collection of education materials showcasing the beauty of New South Wales and the beauty of artists he loved which people going through public schools get little exposure to.

As for me purchasing an outfit from Norman, with items such as the double breasted jacket which he had just brought back into fashion, I guessed correctly that working in public schools in London demanded less sartorial finesse – something more like a bespoke reversible flak jacket.

It would have been interesting to see how such a garment turned out, designed to forefend me against fallout from chalk, leaky pens, projectiles such as paper planes and pellets from rubber bands.

A voluptuary I would not be. The few could keep their frou-frou. Chi Chi was not for me.

Flash Harry

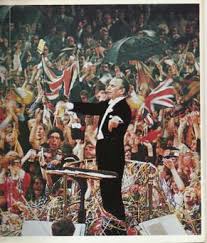

I enjoyed each season of the promenades, the biggest classical music festival in the world. The seats were good, and quite cheap at that. I attended the special yearly concert devoted to raising money to help children with cancer. This kept the memory alive of Sir Malcolm Sargent who set it up. I pictured him sitting near me in the audience getting into the swing of things.

The main venue, the Royal Albert Hall provided an area where part of the audience could move around freely. On certain nights the dress code allowed for fanciful costume – with one exception- unlike the Hyde Park concert I later attended – no birthday suits! The Last Nights of the Proms is a more light hearted, winding down presentation of British pieces such as Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance and Arne’s Britannia Rules the Waves.

I get lumps in my throat with the first piece but with an over the top patriotic audience belting these out amidst a sea of banners and waving Union Jacks at the last night I attended. it made me cringe somewhat. These excesses were eventually toned down.

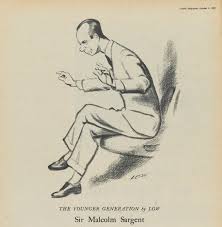

Gazing onto the podium I would always sense the presence of ‘Flash Harry’. This was the moniker of Sir Malcolm, the renowned conductor who had died a few years earlier, and who had been closely associated with the promenades. As a child I had been introduced to his conducting on a scratchy 78 record played on a neighbour’s old gramophone machine.

Sporting his trademark carnation in the lapel of his suit, hair slicked back with Brylcreem, his impeccable dress style suggested someone who had just been togged out in Burton Street.

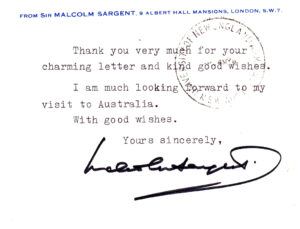

Sir Malcolm had thanked me very much for my charming letter and kind good wishes.

I thanked him for the wide range of music he had recorded and for raising public morale during the war when he had toured extensively with orchestras throughout the blitzed and blacked out country.

I thanked him for the wide range of music he had recorded and for raising public morale during the war when he had toured extensively with orchestras throughout the blitzed and blacked out country.

On one occasion he had to hold off the performance of Beethoven’s 5th and calm the audience during an air raid. Before going on he reminded them that they were safer inside the hall than outside.

Gazing onto the podium a generation later, I would recall that confident grasp of a complicated score and witness that extraordinarily stick technique he had, which television had brought to my attention.

‘Flash Harry’ was in all his glory at getting the best out of the members of the choir. His rival on the podium Thomas Beecham acknowledged that he could ‘get the buggers to sing like blazes’. One piece he would stay with was Handel’s Messiah. He could be depended on to play this every year at the Albert Hall to his faithful following. He encouraged his audience to join in together to hum, clap and sing.

Sir Malcolm played a great part in making British music and British orchestras known abroad. Sir Malcolm told me he was looking forward to his visit to Australia.

The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn.”

At the same time I was observing this established cultured world, I was acquainting myself with a younger less cribbed one which deviated from it musically and in its way of life. John Mellor a struggling young itinerant street musician I was chummy with and about whom I will write later acted as my guide. John knew who I was as soon as he saw me. I met him walking in Hyde Park when this guy waved at me. Then, thinking he was mistaken said, ‘I’m sorry I thought you were someone else.’

I said, ‘I am!’

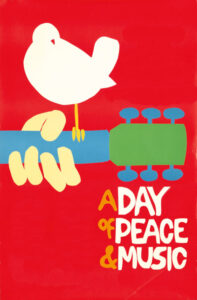

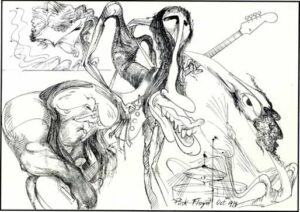

John told me of the upcoming rock concert in the park. He recommended I take note of the Edgar Broughton band. Out there, openly defiant of authority they achieved financial success due to their implacably oppositionist politics and their refusal to follow mainstream musical tastes. Edgar Broughton declared their aim to be to ‘subvert what’s above from below’. Their intelligent, innovative and pleasant music was a welcome feature at the series of legendary free concerts, often for causes, held over this period. I was interested in hearing what they had done to ‘Apache’. I caught them first at the concert held in Hyde Park in July 1970 with Pink Floyd, unofficial “house band” of London’s underground headlining.

Daybreak’s hazy chill saw me in the park assembling with a hard core rock following to ensure a close up, early bird’s eye view of the stage. Pasty white faces were blotched pink from the first hint of summer sun. Warming things up were artistic odds and sods amongst their ranks, providing this boy from the bush with some way-out freaky deaky sights that he had never witnessed. Exposed for the first time to a ritual fire show with performers gamely spewing plumes of fire ruffled by a strong breeze, twirling it on sticks, throwing shapes while shooting plumes of coloured smoke into the air. Acrobats threw circus yoga moves on the grass to the sound of a patchoulied paisley patterned piper heralding the new day. Six of its hours filled with music from some of the best bands in Britain.

With a crowd of 120,000 having flocked there like moths to a flame, it may have lacked the ambience and the intimacy of the earlier concerts but made up for this with enthusiasm. While the Hells Angels were carrying out their self appointed role as the official police at the front of the stage, the sun beaming down convinced a sandalwood scented, crystal pendanted section of the audience near me to get their gear off and frolic with abandon on the grass like fairies in a midsummer’s dream. When the paparazzi homed in for shots of this splendour on the grass, others in the audience quite rightly pelted them with scunge.

After lots of onstage ranting and a rendition of their anthem Out Demons Out! Members of the Edgar Broughton Band led a section of the crowd off on a spontaneous antic demonstration against the state of the nation through the crowded streets of London.

The final act was a performance by the ‘Floyd’ who treated the bohemians of rhapsody to an hour of beautiful soothing and inspiring music.

They kept the number short and carefully restrained. So many people kept their hands in the air. There simply wasn’t enough room to get them down.

The captivated audience was then treated to a brass section and choir, followed by a dash of marvellous trippy Floyd rock-jazz and swirling special sound effects. The concert enabled many to see acts they would never have been able to. It created a special bond between musicians and audience and an atmosphere of bonhomie with the audience. Woodstock with earth, wind and fire – without the mud, sweat and tears.