No Passing Fancy.

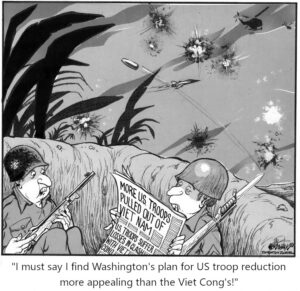

How do you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam? How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?

John Kerry, Testimony before subcommittees of the U. S. Senate, April, 1971

For my university dissertation, in absentia, I had an open brief, able to choose whatever topic I saw fit, with the approval of the faculty. This was something new and exciting for me, my results having previously depended on just sitting for exams, mostly at the end of the year. I didn’t want to waste my time on some dry, ho-hum, abstruse, esoteric, pedantic, prolix jibber-jabber unrelated to the real world, some hieroglyphic screed that would quickly gather dust on some forgotten shelf.

I wanted not to simply regurgitate ephemeral pap but to expatiate on something lucid, animated, cogent, hard-hitting, something that mattered, something widely quoted of relevance to what was being spoken and written about. I wanted to be fully clued into the society I was living in. To explain and evaluate political and social affairs, to diagnose and prescribe change in governance, to combine moral contestation with rigorous analysis -‘protest with perception’- were, for me, the foremost tasks of academic enquiry.

I had hopes of being valued in university communities as bringing understanding to and resolution of campus conflict. I saw myself as being sought after and welcomed as a distinguished visiting scholar.

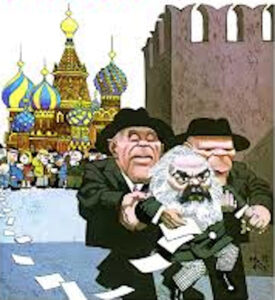

Able to show I was a serious researcher, I registered in the British Museum. I gained Reader’s credentials there in the British Library. I spent so many hours there, I felt like a museum piece myself. Sitting in the reading room, I had a recurrent fantasy about sitting next to the ghost of the old bearded man, the last of the Old Testament Prophets, studying capitalism, it’s injustices and a revolutionary strategy to replace it.

The university would confer the title magna sine laude on me.

They presumably believed I had stepped outside the bounds of academia’s obsession with detached, objective scholarship in favour of political engagement.

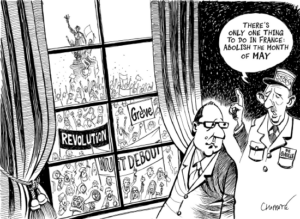

I chose to put under the microscope the activities of the student movement in France and England and encapsulate its ideas. Basing it on exhaustive documentation, personal observations, interviews with those with first-hand accounts, and scrupulous negotiation of disputed facts, I tasked myself with burrowing in depth the upsurge of rebelliousness that had had roared throughout campuses from Berkeley to Prague in the ‘60’s and was still howling amongst young people, to help understanding of this green shoots social dynamic. The spirit of revolution over Vietnam, over injustice, over human rights seemed to have spread everywhere. Youth from across national boundaries called everything vis-à-vis society into question were wild about re-examining all aspects of public and private life and hurled brickbats at their abuses.

Spilling over into the working class, it was the prelude to the biggest anti-capitalist offensive since the end of the Second World War. Lasting seven years, it forced the resignation of governments, brought down dictatorships and rocked the system of bourgeois rule to its foundations.

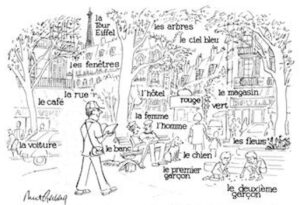

Once I was more clear on the background I proceeded to the foreground. Paris was pivotal to these events. Its uniquely dense weave of narrow streets and broad boulevards — concentric rings reflecting state-of-the-art mid-19th-century urban planning superimposed on a medieval core, with barely a right angle or parallel line in sight — discloses, to all appearances, a limitless reservoir of perspectives and moods. The sun setting over the Seine; the swirl of traffic around the Place de la Concorde; the workaday neighbourhoods on the fringe of the Right Bank; the mansard roofs, high windows and wrought-iron balconies, the storied cafes and restaurants clustered around the Boulevard St. Germain. Love, sophistication, eroticism, danger, class struggle, violence, tenderness, political intrigue — any effect, theme or motif you can contemplate is likely to have a Paris address.

They all coalesced in varying degrees at the office of U. N. E. F., The national student union. Setting out from there, I was taken to others by Pierre, an official, who walked me through the steps of the revolt. First, we bused it to Nanterre, a university in the western suburb, near La Défense a major business district. ‘It sounds like some kind of military zone or establishment’, I commented.

‘The name officially commemorates the soldiers who defended Paris during the disastrous Franco-Prussian War,’ said Pierre, ‘but for socialists it has a deeper significance. We look back nostalgically to the defence put up by the militias of National Guards and the citizenry: workers, artisans, dressmakers, cleaners, who had just spent an impossible winter besieged and macerated by the Prussians. They had a gnawing in the pit of their bellies; they wanted work. They had a bitter memory of the 1848 barricades. Now they were fighting against the bloody final assault on their fast spreading democratic socialist republic, the Paris Commune – the first time the working class ever assumed power, if only for two feverish months. It was here on the western edges of the capital that the Versaillais – the bourgeois government defeated by the Prussians that had taken refuge in Versailles- managed to break through.’

‘How would you characterise this short-lived authority, Pierre?’

‘ It may not have lasted long but it was no nine day wonder. It was a prefiguration of a liberated society. There was a wide variety of political undercurrents, a high degree of workers’ control, and remarkable cooperation among different revolutionists. Doing their utmost to run the administration of Paris, they implemented a program of social reform. This led to the growth of trade unionism which would press for shorter hours allowing workers more time to spend with their families.

It was agreed equality of educational opportunity was the priority for the coming generation. The blueprint was to make further education and technical training freely available to all. School materials were provided free. School children were provided with free clothing and food.’

‘The Germans would have seen this as a dangerous precedent’, I said.

‘The Communards and Guard were decimated in an orgy of merciless reprisals, not directly by the Germans but by the Versaillais, in cahoots with monarchists. They couldn’t beat the Germans but they could crush their own people.’

‘Bourgeois birds of a feather’, I said. ‘Vichyous vultures.’

‘As with the collaborationist Vichy regime, The Paris Commune has always been swept under the carpet by the French education system.’

‘In its case because of the fact that it is a key event in the history of the European working class. Another bloody event. We’ve got yards of skeletons in our cupboards. Graveyards of them.’

So much for Liberté, égalité, fraternité!

‘There’s no brotherhood of man for the bourgeoisie. Their ethos is very much liberté, egalité, canapé.’

‘How do you relate the Spring of 1871 to the events of 1968, Pierre? ’ I asked.

‘We can follow a common thread through the revolutionary moments of 1789, 1848, 1871, 1918, 1968. History constantly repeating itself.’

‘What place does Nanterre hold in continuing this spirit?’ I asked.

‘This university had been established as an annex to the Sorbonne, to unload the dreadful overcrowding there. The number of enrolled arts students only had exceeded thirty thousand. There were few possibilities for putting up new buildings in the densely populated Latin Quarter. Based on the American model, Nanterre was created as a campus (as opposed to the old French universities which were smaller and integrated to the city they were in).’

‘The sobriquets of this huge campus are “Nanterre, la folle” (Mad Nanterre) or “Nanterre la rouge” (Red Nanterre). To this day, the university remains traditionally the centre of gravity of the left wing, as opposed to universities such as Paris II-Assas, traditionally inclined to the right.’

‘This is the cradle and springboard of the revolt, where it actually began in March’68. It grew out of the call for wider university reforms of the archaic system and for greater personal freedoms. It began harmlessly enough with students protesting here.’

‘Against what in particular?’ I asked.

‘Against what they felt were deteriorating university conditions. Overcrowded classrooms, flat indifferent teachers, insufficient space, stifling atmosphere. The list goes on.’

And so did we, going back to the centre, arranging to meet up the following days.

In the meantime, taking in the sights, I discovered much to my great delight that I remembered more high school French than I thought.

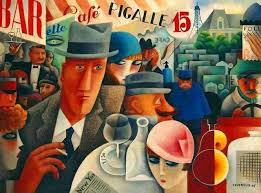

Pierre and rendezvoused in four sidewalk cafés on the Left Bank of Paris’ Seine River, on the boulevard Montparnasse — la Coupole, le Select, la Rotonde, and le Dôme. Pierre ordered coffees at La Coupole, but the waiter protested that at midday one does not reserve the best table in the house merely in order to drink coffee; the patron had to pay the rent, monsieur! Pierre ordered two ham omelettes with frites, and two Alsatian beers.

He told me about this geographic and cerebral hub populated mainly by students and academics from the Sorbonne. ‘Intellectual and artistic social life has long centred around these rallying sites’ he said, ‘meeting places where aspiring researchers like you can occupy a table all morning for a few centimes without being moved on, places whose habitues have long hatched and mulled over many important ideas. An intellectual breeding ground, it’s long been receptive to exiles and radicals staying in small, drafty, high-ceilinged rooms in cheap little hotels. Early in the century Russian political refugees such as Lenin and Trotsky became a part of the intellectual community here. During the “années folles” (“Crazy Years”) between the wars, writers and artists with all their oddities from all over the globe had a thing for it, haunting the bistros, the nightclubs and the low-life dives that are sometimes ‘amusing’ at the end of a long evening.’

‘For the current generation of students, it’s their natural habitat. A place to seek oneness.’

‘It was here on May 3, ’68, where things quickly gathered pace. When several hundred students protested the closing of Nanterre University, the disciplinary hearings against students who had been trying to be treated as adults and not as children, and the jailing of these leaders for this action. They were attacked, tear-gassed and arrested by police. The vans taking away the arrested students were surrounded. A crowd developed and started to angrily push forward. One of the vans never made it out. The prisoners were released. There was heavy handed police treatment of an unprecedented level. This inflamed the situation further. The clashes bled into all the university area and by nightfall 500 had been arrested and 100 worked over. In the following days thousands of high school and university students and teachers went on strike throughout the country, protests were held throughout the city and barricades set up. Students refused to take the violence against them, counterattacking.’

“Pour faire les quatre cents coups”, I said quoting the Truffaut film. “To raise hell”.

‘The residents of the Latin Quarter, the headquarters of the University of Paris, helped them raise it. The special riot police that had been created after the workers’ strikes of 1958 were then mobilized, leading to episodic but fierce street battles in the Latin Quarter.

‘Paris being set in stone’, said Pierre, looking out at the limestone facades of most of its buildings lining the street, it was only natural we retaliated with what came to hand. The cobblestones of our sidewalks.’

In a show of solidarity, instinctively siding with the students, ten million workers, or roughly two-thirds of the French workforce, went on the biggest wildcat general strike in French history, occupying factories, against the will of their union leaders. Beginning with the Sud Aviation plant in Nantes, where they welded the plant gates shut on May 14, and leaping to the complex of Renault auto plants around Paris, where the workers ran the scarlet banner high. In some cases, they kept their bosses imprisoned as they insisted on wage increases, better conditions etc. The country tied up, De Gaulle’s government was brought to its knees. The President met secretly with his generals and created a military operations headquarters to deal with the unrest.’

‘Une force majeure.’

‘Except for a weak link. The French Army was not necessarily “reliable”. De Gaulle dissolved the National Assembly and called for new parliamentary elections. What appeared in January to be a relatively innocuous dispute between students and the government turned, within the space of a few weeks, into a revolutionary situation. We were the fuse; the workers were the powder keg,” said Pierre. ‘As with the Commune, there is not a shred of evidence that the government had expected or planned for the crisis under way that broke over their head.’

It left a dramatic reminder to future leaders of the lasting potential for a revolutionary social challenge.

‘Then it evaporated almost as quickly as it arose,’ said Pierre.

‘Like the Commune, its sudden rise was equalled by its swift demise’, I commented. ‘What was the reason for this, Pierre?’ I asked.

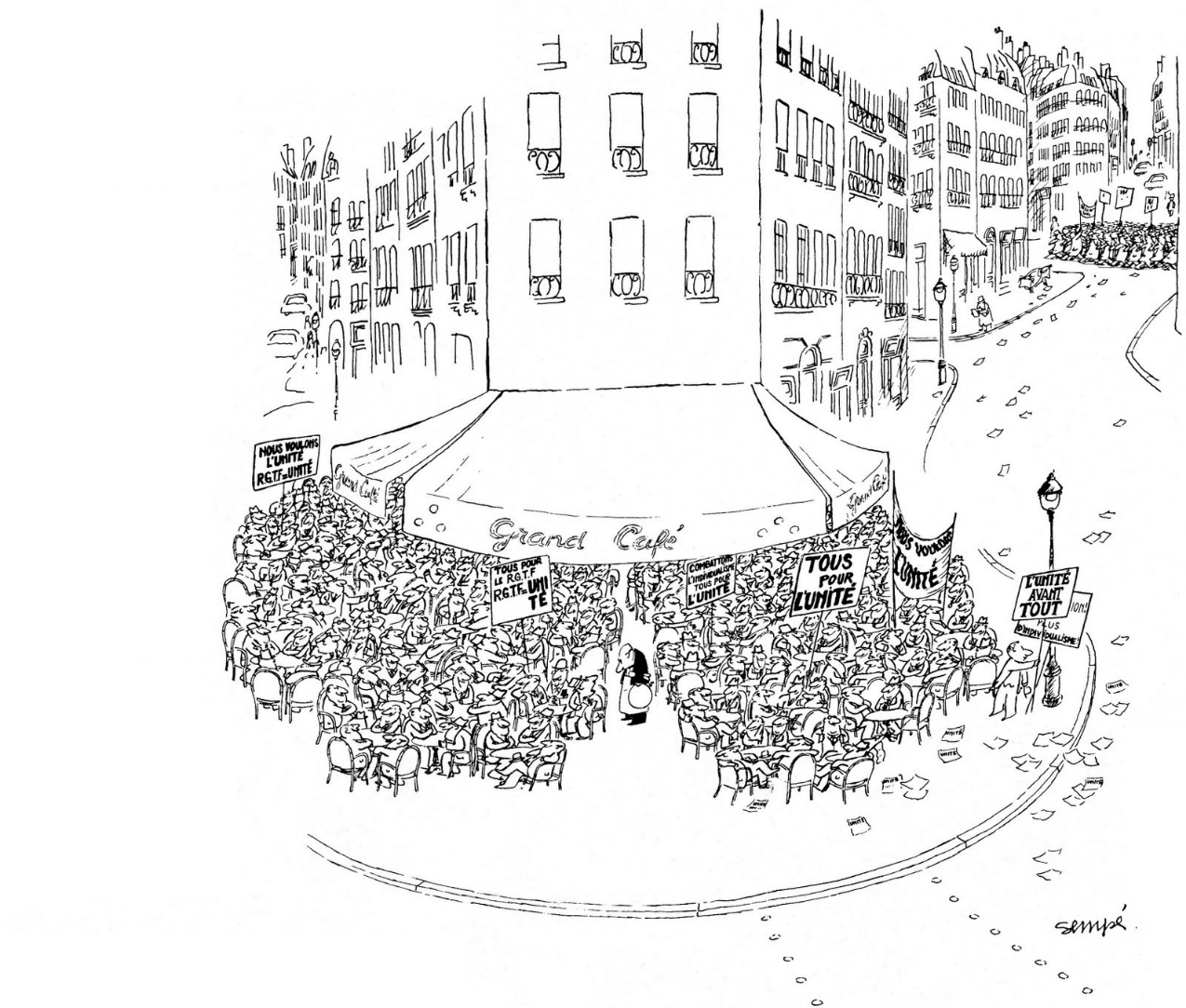

‘There were many factors, most prominent being the divisions within the French left. De Gaulle’s 5th Republic government was able to diplomatically end the strikes by negotiating with the PCF (the French Communist Party), and the CGT (Confédération général du travail). Workers went back to their jobs, students to their classes, and the government emerged even stronger than before.

‘Many would have expected the Communists to support you’, I said.

‘Quite apart from the hostility of the Gaullists, we had to suffer their frequent hostility,’ he said. ‘At the heart of the debates during and after May 1968 was the question of our future direction: reform versus revolution. In the political context of France this pitted us gauchistes (Maoists, Marxists, Trotskyists, students) versus the PCF (the official French Communist Party) and the CGT (Confédération général du travail). It was a case of the radicals versus the moderates, with the former wanting wholesale changes to society and the latter wanting to mend it from within.’

Pierre said, ‘There’s going to be a Manifestation against the war on Vietnam in a few days’ time. I take it you’ll be coming?’

‘Naturellement,’ I replied. ‘Wild horses couldn’t keep me away.’

‘What about police horses dragging you away?’ came back Pierre. ‘Just joking. We don’t expect any trouble today. Not like the ones I’ve been telling you about,’ said Pierre. ‘Demos against the war are a different – how do you say – kettle of fish. Today we’re not rallying against the government, because it opposes the American presence in Vietnam. However, the guilt of our colonial past with Algeria and Indochina, the prelude to the Vietnam War, weighs heavily on our collective memory.’

‘On ours too,’ I added, ‘to say nothing about that of the Vietnamese .’

As it turned out this was the most massive demo I would ever attend. l got cut off from Pierre in the mighty melee at the end.

‘When and where will I see you if I lose contact with you, Pierre?’ I had asked him beforehand.

Whether he had replied ‘apres de la guerre,’ or ‘pres de la gare’- ‘after the war’ or ‘by the train station’ – I had to decide when we did get separated. I went to the train station as it was quite clear Nixon would do nothing in a hurry to bring about a culmination of the conflict that had driven Lyndon Johnson from office.

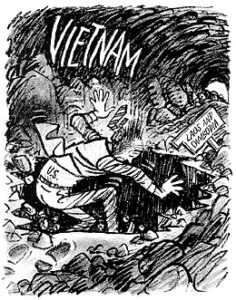

Instead reassuring everyone the US never wanted a wider war, he had sent troops into Cambodia and Laos. This strengthened the Khmer Rouge and Pathet Lao. The light at the end of the tunnel had led to another tunnel.

His strategy of Vietnamization was a desperate gamble.

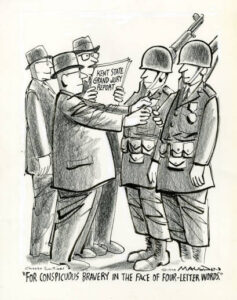

Those gathering at peace rallies were now considered reasonable targets for the military.

The Ohio National Guard opened fire on protesters.

The state grand jury recommended charging 25 people with crimes over the killing of four students at Kent State University—none of them guardsmen.

The state grand jury recommended charging 25 people with crimes over the killing of four students at Kent State University—none of them guardsmen.

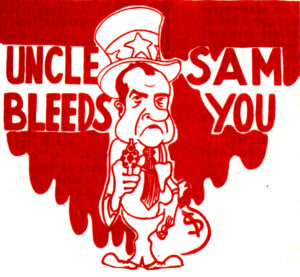

The Paris peace talks were going nowhere. Officially, they were said to be ‘useful’ which meant nothing was being accomplished. In spite of all that the current military campaign by Nixon to ‘bomb those bastards right off the earth’ kept hitting new lows. Defying him, the media he called those ‘dirty rotten jews from New York’ exposed military massacres. Every day soldiers were still being sent to Vietnam.

Thousands of them had already paid the supreme sacrifice or had been injured.

Tens of thousands of Vietnamese had died in the war. When I got up on Thursday, things were no different in Vietnam despite what millions of us had done the day before.

Yet what at first seemed like a hopeless global anti-war campaign with no horizon whatsoever ended up winning, within two short years, with Nixon withdrawing troops from Vietnam.

The last helicopter would leave Saigon in defeat.

That massive demo and the student movement made a huge impression on me: the sheer ambition of mere students after all, their tactical and strategic smarts, how they were willing to confront the full power of the state.

For the first time in my life, I had seen political ju jitsu at work. I had seen that small forces such as these, if applied correctly at a particular pressure point, could be used to leverage political change, that it was possible to look at building such political change around a strategy where the weak could use tactics to defeat the strong.

I felt very much in tune with this wave of youth radicalization, in sync with the vanguard moving for change and progress in politics, religion, class struggle, racial issues, and the Vietnam war. The Zeitgeist I was writing about and fully embraced was one in which there was a torrent of questioning of old moral truths and certitudes, in which all the old institutions and morality were placed under close scrutiny, shaken up, where many youth aimed to change all of the contradictions that remained unchanged from their parent’s culture.

Not least of these was the nature of the Soviet Union. Churchill had famously quipped about Russia that it was a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. It was no longer seen as such a mystery. Unlike in the 30’s when it had been seen as the vanguard of political progress, it was a commonplace that it had transmogrified and had a lot to answer for.

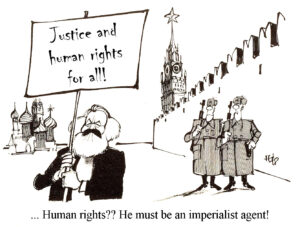

This was a perverse, deformed workers state that had betrayed its socialist principles through its abuses of human rights, covert actions against, and disrespect for the sovereign rights of its neighbours, even when they presented no threat to its security. “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss”.

Karl Marx had been a fervent advocate for human rights. I wondered how if he were to have come back to life in the U.S.S.R this would have been considered.

I wondered how he would have been handled.

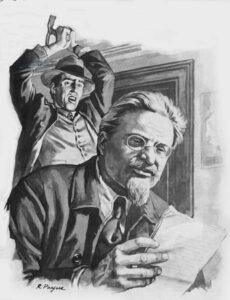

I found Soviet practice a mockery of its pre-Stalinist ideals, its most brilliant revolutionaries having been persecuted, murdered and expunged from its annals.

Stalin added himself and his own trumped-up exploits in their place.

The Soviet military had been weakened by the grave digger of the Revolution during the “Great Purge” when, fearful of a coup, he had vast numbers of soldiers and top officers murdered.

He carried out forced deportations of whole communities, such as removal of the Tartars from Crimea.

One sign of a revolution is that the first victims are the moderates. And then it becomes a struggle between the extreme forces on either side.

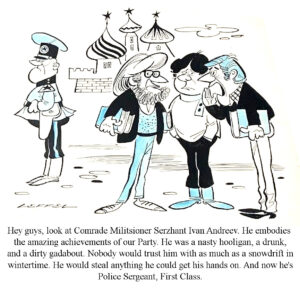

I found deeply reprehensible the policies of the pale, male and stale Soviet doctrinaire leadership .

Its confusing pre-war demoralizing turnabouts, one minute scoffing at social democrats and New Dealers as ‘social fascists’, the next building fronts with them. Lenin had envisioned a provisional state without standing army and police, a state constituted by “a people in arms,” not by a top-heavy bureaucracy, rather a state progressively dissolving in society and working towards its own extinction.

Instead of merging with a “people in arms,” the new state, like the old, was separated from the people and elevated above it. Reabsorbing much of the old tsarist administrative machine, It became bloated, mendacious and self-congratulatory. The Soviet knight was dying in its armour.

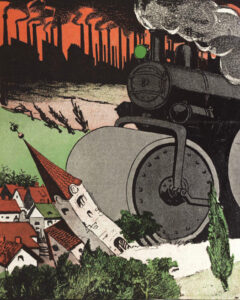

One has to understand the extenuating circumstances that led to this mutant form depending on achieving its ends fighting fire with fire: the hermetic sealing-off of the revolution; the poverty, the shambles, the backwardness of Russia, the environmental despoliation resulting from rapid industrialisation,

it’s uneven development due to the urgency of military defence ;

the anarchic individualism of the peasantry; the demoralization of the small working class, dispersed, exhausted, apathetic, demoralized, gone to seed. Revolutionary Russia could not have survived without a strong and centralized state. It was written in the tsars.

A “people in arms” could not defend her against the White Armies and foreign intervention – a severely disciplined and centralized army was needed for that. The Cheka, the new political police, were seen as indispensable for the suppression of counter-revolution. It was impossible to overcome the devastation, chaos, and social disintegration consequent upon civil war by the methods of a workers’ democracy. The nation could not regenerate itself by itself, “from below”.

Lenin saw that a strong hand was needed to guide it from above. Taking this to the extreme, Stalin tightened control giving no quarter, brooking no dissent, leading to the revolution degenerating irredeemably. It descended into chauvinism, re-establishing the “one and indivisible” Russia of old by giving next to unlimited powers to the central government in Moscow, total control over the media that someone like Nixon could only dream of.

It turned a one party dictatorship into a one man dictatorship, depriving the national minorities of many of the rights hitherto guaranteed to them, clearing the path for Stalin’s hurricane of perfidy and murder. The revolution’s gravedigger withheld a letter to the Party from Lenin, warning against his having gathered much too much power in his hands, and that the party would be well advised to remove him from the office of its General Secretary.