The Most ‘Dangerous’ Man in the House.

The biggest men and women with the biggest ideas can be shot down by the smallest men and women with the smallest minds. Think big anyway.

Hedy Lamarr, screen actress and inventor.

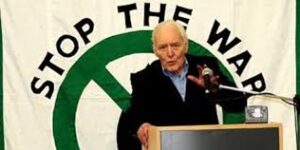

My history students from Isaac Newton School and I made a class trip to attend an “Educational conference” at the Methodist Hall in Westminster. I didn’t have difficulty getting approval as the speaker was the Secretary of State for Industry.

He had shortened his first name from the less plebeian Anthony and dropped Wedgewood. Tony Benn was talking on his portfolio in the Labour Government returned that year, 1974, and on democracy.

I primed my group of mostly Caribbean British students, including Delbert and Delilah, telling them of his role as Minister of Technology in the Labour Government’s program of industrial reorganisation:

’There is a parable from the Sermon on the Mount about the foolish man who built his house on sand and the wise man who built his house on rock. Mr. Benn wants to lay a new foundation for growth and prosperity in this country. ‘We cannot rebuild this economy on the same pile of sand,’ he says. “We must build our house upon a rock. We must– a foundation that will move Britain from an era of borrow and spend to one where it produces, saves and invests more; where it competes better on the world market.”

He believes these goals are best served by having a strong single service provider in each sector of the economy. From railways to airlines, telephone to fuel, the British state can provide all through one-time household names such as British Rail, British Airways, British Telecom and British Gas. He has given support to companies which employ new technology and fund computer development.

He recognised Britain’s need to develop high-quality cutting-edge engineering as the way forward. To increase economic growth, Mr. Benn arranged mergers of strategic companies to compete with the American giants. He merged struggling computer companies, thinking that only one big British tech company could act as a national champion and stand up to IBM. He pulled the same trick to form a ‘national champion’ against US car makers. ‘To save the motor industry’, he arranged the merger of several car companies to create British Leyland .

Benn’s other great act was in stewarding Concorde to tackle Boeing’s dominance of the aircraft market.

It pioneered advanced technologies such as the double delta shaped wings and a droop nose for better landing visibility.

He says he would never have started it, “but there were a quarter of a million jobs at stake.’’

Others can take credit for designing and building it.

However Benn successfully resisted Treasury efforts to cancel it because of spiralling costs. He also restored the letter “e” to the project’s name, which had been removed by former Prime Minister Harold Macmillan after a falling out with Charles de Gaulle. ‘E stands for excellence, for England, for Europe and for the entente cordiale,’ Benn said.

But now his is a particularly sensitive and trying post. The fall of the Wilson government in 1970 and the election of the Heath Conservative administration produced a widespread radicalism. It has permeated the labour movement, including the Labour Party. Mr. Heath’s attempt to introduce anti-trade union legislation led to a massive campaign of opposition, starting with the unions.

The present time is characterised by deepening class struggle, what with the national miners’ strike in 1972 and the one we’ve just been having. This is a time of great upheaval and many are coming to question the economic system. Mr Benn is at the centre of this storm.’

Unassuming and gracious, Mr Benn arrived carrying his briefcase and sat down while a teapot was before him. Five minutes behind his scheduled start, he whispered an apology, ‘My bus got caught up in the traffic.’ A prodigious drinker of strong, unsweetened Darjeeling tea, he rarely went long without any. He had difficulty getting a good solid grip of this pot in order to tilt his wrist when pouring.

I said, ‘Look at the handle. It’s positioned too low and it’s too small. It should align perfectly with the spout forming the main axis of the pot, so the horizontal balance and pouring position are both easy and comfortable. It’s size is determined not only with visual balance but rather leverage balance of weight of the pot body. A lot of teapots come with smaller than needed handles, I think for economy of packing space during transportation. As Industry minister you might assign someone to sort this out this design fault’. He smiled broadly and said, ‘You’ve obviously spent some time thinking about teapots.’

Having drunk his cha, he then stepped up to the wooden lectern and went through the procedure of adjusting it for height and slope. He spent a lot of time thinking about the humble lectern as a tool in politics. It helps one’s posture and hides the waistline. It brings one’s speaking notes that much closer to the eye to allow for the ravages of age on eyesight. And it allows better audience eye contact.

A keen amateur inventor, this modernist who long saw the worship of the amateur as a British vice would later design and build a lectern for himself. One of Gadget Man’s ideas would be to design a homegrown briefcase that could be converted into a makeshift lectern. But for this day, he was happy to make do with that provided by the Methodist Hall.

He had a rare gift of oratory that he had mastered as a young man.

In his softly sibilant sonorous voice, ‘Politics is about issues not personalities’ sounded as ‘ishoos not pershunalities’ from his lips.

Unlike other politicians, who used the opportunity as a platform to ‘thump the tub’ and promote their narrow party policies, Tony Benn spoke about topics from the current situation to the history of the labour movement, speaking with passion and illumination about democratic issues and practices he believed in:

‘Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, experience being the only real teacher, my aim here today is to talk about mine and use it to give understanding. To give my best explanation about which direction our country and our shifting world is going in. I love exchanging ideas with you young people in particular as our future is in your hands. I describe myself as an untrained classroom assistant to the nation, so I’m here willing to learn from you all and to talk about my ideas.

The most radical and revolutionary one and closest to my heart is democracy. The powers that rule us talk about it. But they resist it with all the wiles and techniques at their command. Why is this, you might ask? The answer is simple. Democracy transfers power from the market place to the polling station, from the wallet to the ballot. Stalin wouldn’t allow it. And the way I see things, some of our own leaders are not all that keen on it. Nobody in power likes sharing power with anyone else.

However the baseline of democracy is the belief that we were all born equal and that equality must be accepted by those in power. If there’s one main lesson I’ve learned in life it’s this: If people don’t keep up rattling politicians’ cages for democratic control, they lose it. It’s ‘use it or lose it’, and that is something people find hard to get across.’

If there was a party political element in his address, it was never apparent. In this way I judged him to have far more integrity and intelligence than other politicians.

He fielded a wide range of questions about these matters from teachers, students and interested members of the public, both critical and supportive.

‘You were rather a headache for the Heath government, weren’t you, Mr. Benn? In 1971 you leaked a paper written by the Conservative politician Nicholas Ridley. Did you have any reservations about doing this?’

’‘None whatsoever. This paper advocated a complete government withdrawal from the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, the consortium of five shipbuilders my department assembled in 1968. The restructuring I implemented was a much more acceptable solution to rundown. Ridley had drawn up highly confidential plans to “butcher” the semi-nationalised Upper Clyde Shipbuilders –the UCS– as a ‘cancer’ that was forcing up wage rates in the private yards. The Tories were going to hive off the shipbuilding units. There were to be mass redundancies and sell offs to private sector. The shop stewards’ co-ordinating committee seized the initiative, occupied the yards and announced that it was establishing a work-in and production would be maintained. Those declared redundant would continue to work and be paid. I encouraged the UCS workforce in this approach rather than striking. The men were engaged in this, part of industrial action that lasted a year and inspired workers around the world. The shrewdly organised opposition to closures by the workers and their mobilisation of Scottish opinion wrong-footed the Tory administration. Heath eventually conceded defeat, and invested £35m in the shipyards.

‘What was the lesson to draw from this?’

‘The lesson of the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders’ work was that this was an effective way of defending industry from the predators who only saw assets to be stripped. It raised the prospect, if only temporarily, of a new style of ‘worker power’.

‘What do you see as your government’s involvement in industry, Mr. Benn? Some see it as just spender of last resort, shoring up critical lame duck concerns. Can you satisfy the tax payer that the best use is being made of public funds when it invests in industry?’

‘We want to move to a situation where the public sector is not kept as a loss maker by government intervention. We don’t want the unviable private sector kept profitable by government support. The big firms at the top must be made accountable for their decisions.’

‘What do you see as the main obstacles to further industrial development in Britain?’

‘We have identified some deep-seated problems of inadequacy. We’re battling to cope with a variety of British industrial “diseases” – under-investment, poor productivity and management. To deal with them requires some big democratic reforms. We want government to play a leading role in protecting and promoting industry. This includes securing partial state ownership of profitable companies.’

‘Should the government do more to ensure that private capital can make increased profits?’

‘I am for more profits if it means developing our resources more, re-invested profits. But the plea for higher distributed profits- those distributed to shareholders via dividend payments- is a different matter. It would be very easy to make firms in difficulty like British Leyland more profitable by carving them into pieces. But this would be against the national interest. The point is we have not found ways of recycling savings to investment in the new tools we need. The old system required a high degree of inequality to work. People won’t accept that now.’

‘Did you consider alternative ways of using public funds other than supporting British Leyland ?’

‘The government does not dictate the pace of industrial change. It is forced by events to interact with reality. Shop stewards in firms all over the country are worried about jobs going abroad. They’re concerned about the extreme age of many of the machine tools with which they work. But labour is not interchangeable in the pattern of it’s skills or geographically. And redundancy does not play a big part in ensuring redeployment to alternative work. Government must work hand in hand with both business and unions to promote our industries.’

‘You seem to be boosting the tea industry singlehanded’, one of my students, Delbert, said. ‘You’ve always got a big mug in your hand when I see your picture in the papers.’

‘I estimate that I’ve drunk enough over the course of my life to float the QE2.’

‘As for that other source of liquid energy, oil, should exploitation of North Sea fields be handled like in Norway?’

‘Absolutely, ’said Tony who had opened a discharge valve to release the first consignment of oil from the North Sea into a refinery.

‘The benefits of oil should not simply flow to multinational oil firms but should be shared by the people now and in the future. Oil revenues should be put into a special fund for future investment. The oil bubbling ashore should benefit British society at large. Oil revenues should be ring-fenced for industrial regeneration and not used to finance short-term tax cuts. An oil-rich Britain would be in a stronger economic position outside the EEC.’

‘Doesn’t Britain’s future lie with the greater family of six European nations and the U. S.?’

‘ The future is not what it used to be. We have been told for years that this nation is not good enough to govern itself, that it has to be governed from Brussels or the Pentagon.

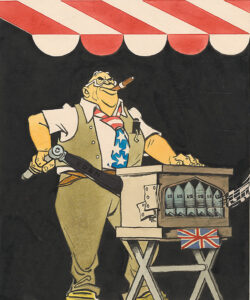

Let me remind you the U.S. has been known to fly it’s B52s laden with nuclear weapons over our skies in breach of our agreement that it not do so.’

We have been told because world capital is so powerful, the country must integrate itself deeper and deeper into the structures of Europe and the U. S. where power is bigger.

We have been told that we cannot defend ourselves but must have NATO. We’ve been led to believe that we must have the latest missiles that the the US defence contractors are drumming up sales for.

We have been told that we cannot organise our economy and must follow the IMF and the ‘Gnomes of Zurich’. We are told that this is a nation of lazy workers—militant shop stewards, inefficient managers and football hooligans—a nation waiting for discipline. Of course, the discipline will come from these more powerful states.’

‘Don’t we rely on these other countries to help solve many of our problems?’

‘This country’s problems will be solved in Britain by us, and only when we have solved them will it be in our power to have satisfactory relations with other countries. Let me put it simply: communism run by Commissars from Moscow does not work, nor will capitalism run by Commissioners in Brussels. Both deny people their right to develop in their own way. Market forces deny us a stable industrial base. One cannot close down Rolls-Royce today and open it tomorrow, any more than one can close down a farm today and reopen it tomorrow. Skill is what built this country’s strength, and it must be treated with respect. If we want an industry, we must see to it that there is an industry. We do not leave the police, army and hospitals to market forces; we decide to have them. Agriculture has been sustained that way. No economic magic—devaluation, floating pound, exchange rate mechanism or independent central bank—will guarantee that Britain retains and expands its industrial base. The people have the right to decide the future of this country.

The treaty that was meant to unite Europe has divided every nation, every party in Europe and every party in the House. I have never known anything more divisive.’

‘Some would call your attitude anti-European and Anti-American. What do say to that?’

‘To talk of being pro-Europe or anti-Europe is a plain lie. We were born Europeans and will die Europeans. It is a matter of geography. The question is what sort of Europe it will be. Am I anti-British because I do not like a Prime Minister being pro EEC in his policies?

Of course not. Is one anti-American because one does not believe that they should have done this or that in Cuba?’

‘What do you see as the most important cause of the Labour Party?’ I asked.

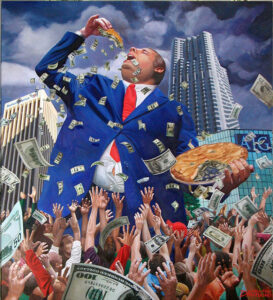

‘The main cause is to bring about a “fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of wealth and power in favour of working people and their families. The Victorian Conservative reformer Disraeli once said that the country contained two nations—the rich and the poor. Today, this disparity is in danger of becoming just as apparent.

We have to create one nation by working towards the speedy common ownership of the means of production. It is a social-ism. It’s about trying to construct a society round production. Around meeting people’s needs and not just for profit, that’s what it’s about. This is what working people either aspire to, or would do when political consciousness has been forged in struggle.’

‘The NEC, the governing body of the Labour Party, has proposed that a Labour government should nationalise the top twenty five companies. What do you say to this?’

‘This indicates the growing pressures from below to implement Clause Four of our party’s constitution. The only reason we ever got democracy was because those in power thought that if they didn’t concede it there would be a revolution. Fear is what makes those at the top concede power. All progress has always come from underneath, by demands made that can’t be resisted. Even Heath u-turned to nationalise Rolls Royce. A Labour government should embark on a process of nationalising the ‘commanding heights’ of the economy.’

‘We don’t want simply the crumbs, we want the bakery!’, called out one man.

‘How are the unions involved in all these changes?’

‘They are working in co-operation with us and business to maintain jobs. Regrettably we have failed to identify the role and rights of the trade unions. We must tap the wealth of ideas coming from the bottom in industry. I have seen shop stewards like those at Fords make some very shrewd assessments of market trends for the future. A Labour government has to dismantle controls on unions left by the Tories.’

‘How far do you see shop floor power going? Would you be prepared to see workers exercising a veto over management decisions, say on investment or production?’

‘That kind of power already exists. But it is only being used negatively at the moment. Workers are accused of throwing spanners in the works, but that is the only time they’re allowed near the works. The power to go on strike and dislocate the system should be converted into a positive power. Actually our policies have made many demands on working people and given them more responsibility. They should be able to scrutinize company accounts. They should understand the basis of decisions being made. There have been some really big changes in trade union attitudes – as over British Leyland. Industrial democracy is something of a hurricane of change. I cannot give a blueprint of how it will work in detail. But in the end it will ensure much more stability in the political and industrial system than if it is resisted. That is the lesson from the past struggle for the right to vote.’

‘Mr Benn, there are those who say Labour is just a prop of a dying capitalism. They say it is betraying its activists, its voters and its history. They say it’s delinquent in it’s mission to change society. Instead it changes people to make them accept society as it is. They accuse it of’ controlling wages, effectively lowering workers’ living standards through cuts and blunting the edge of trade-union militancy.’

‘I’m against any cuts. They trigger trouble. I’m very doubtful about the theory that public spending cuts are the answer to our problems because we’ve made a lot of cuts and on the whole the economy is no better than it was to begin with. I’m trying to implement agreed Labour Party policy put at two general elections. We have to honour our “social contract” with the trade unions: restraint on wage claims in return for legislation that is just and fair to the unions.’

‘How should the Party be governing in your view?’

‘We are not just here to manage capitalism but to change society and to define it’s finer values. Society should be judged not by how it treats the richest, but what it provides for the poorest.’

‘Don’t market forces provide for this? I wish I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard capitalists talk about this idea of choice, telling us ‘The market gives us choice. You’ve got to have a choice. What do you say to this?’

‘Choice depends on the freedom to choose. If you’re shackled with debt you don’t have a freedom to choose. People in debt have less choice at the ballot. They become hopeless and hopeless people don’t vote.’

‘There are still many people who live in comfort and are quite happy with what capitalism provides them with?’

“You’ve got to judge a country by whether its needs are met and not just by whether some people make a profit,” Benn said. ‘I’ve never met Mr. Dow Jones, and I’m sure he works very, very hard with his averages — we get them every hour — but I don’t think the happiness of a nation is decided by the share values in Wall Street.”

‘Where are your ideas going at the moment?’

‘I’ve been developing ideas of industrial intervention, democracy and decentralisation. While I was Minister of Technology, I came to the conclusion that if we were to control modern technology, we needed new democratic machinery. The Labour Party should support industrial democracy, workers’ control and a planned economy. We have to speak up for those whose voices are ignored. We hear now more from the ecologists about economic progress. They are concerned about the quality of change. The Labour Party must align itself with the women’s movement, the black movement, the environmental movement, the peace movement, the rural movement, the religious movements that object to monetarism and militarism.’

‘You mentioned the black movement’, asked Delbert. ‘Yet someone told me you agree with Enoch Powell. He says that because we’re here, Britain is ‘heaping up its own funeral pyre’.

‘I agree with him only on the matter of Britain being in the EEC, the need for import controls and restrictions on the export of capital. His ideas on race are very damaging and make our country less safe. That’s why he’s had to resort to accepting a parliamentary seat in Northern Ireland.

He was in India in the war and was fond of India and I said ‘If you’re so fond of India why don’t you want Indians in Britain?’ and he just smiled. The fact that I respect him does not mean I agree with him. You have to grant him one thing, though. Enoch says what he means, and that carries authenticity with many. He has the finest mind in Parliament- until he makes it up.’

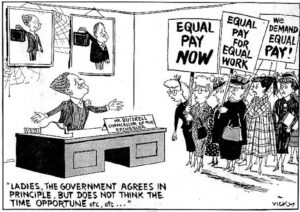

‘And the women’s movement? How can they get better rights?’ asked Delilah.

“They have to do it mostly by themselves.

Our administration brought in the the Equal Pay Act in 1970. It prohibits any less favourable treatment between men and women in terms of pay and conditions of employment.’

‘You must be proud at having given them that.’

‘No one gives us our rights. Female workers lobbied hard for equal pay.’

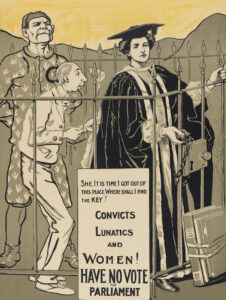

You know, You know, before 1918 women, along with convicts and the mentally ill, were denied suffrage.

When I was born in 1925, women were not allowed to vote ’til they were 30. Men were so arrogant they patted the women on the head and said, ‘You’re not quite mature enough ’til you’re 30′. Now women didn’t get the vote because men woke up one morning and said, ‘We’ve been a bit unfair to the wife’. The Suffragettes chained themselves to the railings, one of them in the House of Commons. They were arrested, they were convicted.

They went to prison, they went on hunger strike, they were forcibly fed, and created such a row that women got the vote.’

‘Can’t the parliamentary system solve society’s injustices for us?’ asked another of my students.

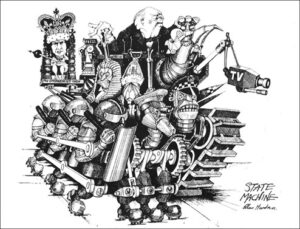

‘Not unless it’s reinforced by mass action. Parliament doesn’t respond quickly enough to the mounting pressure of events or the individual or collective aspirations of our community. You’ve got to understand Parliament has almost no role in checking the executive branch. Judges, heads of the diplomatic service, or Foreign Office and senior bureaucrats of all kinds are appointed by the prime minister without any confirmation. The names of many of them, such as the head of the Secret Services, cannot even be legally divulged. An Official Secrets Act covers all manner of disclosure and punishes any discussion of the workings of state institutions. As a result, the executive branch has become almost impervious to the legislature. Consequently very few large decisions are made in Parliament anymore. And what power it has is only on loan from the people. If you’re an ordinary MP and the factory workers are made redundant, there’s nothing you can do but protest.’

‘Surely if you’re a Minister you wield lots of clout?’

‘If you’re a minister, you have a modicum of power. You can say ‘Right, I’ll do this, I’ll do that, I’ll do the other. At times I have been able to resist demands on big companies trying to lay down the law. But of course there is lots of pressure from the departments and from your colleagues to say ‘These things are inevitable, it’s the hard facts of life, you don’t want to upset the apple cart, there’s nothing can be done, we’re ahead in the polls, let’s leave it at that.

A lot of new ministers are a bit overawed by civil servants. “Come and have dinner, we’ll discuss it,’ they are told. And then the sort of hint that if you’re a good boy you’ll get promoted and you’ll end up as Lord Fauntleroy. The establishment rewards you if you do what they want you do,” he said. “very, very richly. Patronage is a very powerful force.

For this very reason you and I, Uncle Tom Cobley and all have to mobilise people behind us to to gain more direct control over your elected representatives and champion the causes we care about. Democracy is not just marking a ballot paper with a single cross once every five years and watching soap operas on TV in between and wondering why nothing happens. Democracy is what we say and do where we live and work.’

‘How can you be sure that mass movements can be successful?

‘The introduction of the welfare state, along with the movements that won independence in the colonies, confirmed for me that mass movements, combined with parliament, can transform society in favour of the poorest people.’

‘To what do you attribute your move in a more socialist direction whilst in office?’

‘I’ve learned some big lessons in government. I’ve come to the conclusion that Britain is ruled by vested interests. MPs deputed by their constituents to act on their behalf wield little power. As I’ve just pointed out Britain is only superficially governed by MPs and the voters who elect them. Parliamentary democracy is, in truth, little more than a means of securing a periodical change in the management team, which is then allowed to preside over a system that remains in essence intact.

Industrialists and bankers use any means available to exert economic pressure to get their own way, including blackmail.

Just how would the political establishment would react to a victory by a Labour leader with ideas like yours? How would such news go down in the Athenaeum?’

Stretching the political elastic to its limit, one thing is for sure, his honeymoon would be short. The election of such a leader could be greeted by a huge run on sterling orchestrated by Treasury civil servants. A leading trade unionist might be persuaded to organise a power industry strike, leading to blackouts.’

‘So the opposition to any such new government would be sabotaged by those who feel they’re bound to lose their entrenched interests.’

“Civil servants often abuse their power and frustrate the endeavours of popularly elected government. Many of our own Labour leaders rather than acting as teachers have a habit of treating the party as their personal kingdom and running it in a centralised, authoritarian way.

The power of the media is like the power of the medieval Church. It ensures that events of the day are always presented from the point of the view of those who enjoy economic privilege. Owned by a handful of conservative families and businesses, this echo chamber systematically misrepresents the workers. The media barons would have done their groundwork well before any successful socialist electoral victory.’

‘ Suppose that any such leader was to make it unscathed to the general election. Suppose, too, that the country was wearying of the Tories and their endless austerity, and that the polls had begun to predict that the gap between the two parties was closing.

‘The Conservatives and all their friends in the media would, of course, attempt to organise mass hysteria. Any deficit inherited and the balance of payments could be talked up, and a crisis easily organised.’

‘It seems it wouldn’t be long before it all becomes unstuck.’

‘The tricky moment would come when things started to go wrong, as they do for all governments. A few bad polls, bad economic news, electricity blackouts, a blockade of oil refineries … at that point, our socialist leader would even face a challenge from someone within his own ranks, perhaps in league with the forces of reaction.

Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls. I’m afraid to say after all these centuries of history, one thing is true. The emperor still has no clothes. No one believes he has of course, but because of what we’re systematically being told and discouraged from examining, most everyone believes that everyone else believes it.’

If the British people were ever to ask themselves what power they truly enjoyed under our political system they would be amazed to discover how little it is, and some new Chartist agitation might be born and might quickly gather momentum.’

This M. P. who believed socialists can and should use the despatch box as a platform for addressing the masses outside the political snake pit had a simple message: ‘All significant progress always comes from outside Parliament.’

‘We had full employment in the war. It should be possible in peacetime. And it’s only working people who can bring this about.’

‘The war affected you deeply, didn’t it.’

‘I was here in London during the Blitz. And every night I went down into the shelter. Many people were killed, my dear brother was killed, my friends were killed. Millions didn’t come back from that massacre of potential. This was a war that ripped families apart, gave birth to the UN and a promise never to repeat the brutality of the past. And when the Charter of the UN was read to me, I was a pilot coming home in a troop ship. We the peoples of the United Nations determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind.’

‘Were there any positive lessons to come out of this tragedy?’

‘When our countrymen and I came back, we’d learnt a great truth that progressed mankind further than at any time in history. We learnt that when we all pulled together, just sisters and children and fathers and sons, that when everyone had enough to eat and everyone had work in a common shared purpose, we were happier and healthier than we’d ever been. We learnt that if we could spend money killing, we could spend money building hospitals and schools and houses.

The war gave birth to the healthiest, wealthiest, best educated generation of Britons of all time. The “baby-boomers” of today know that they saw the best years. It made most of us socialists, Lord and pauper alike. For a while at least. And our greatest triumphs, our proudest moments came from the debris of that failure.

History shows us that big progressive changes in society are driven not by political elites, but by the endeavours of ordinary working people. The politics in your own lives, in the community and in your workplace can be for you. Especially you young people.’

‘Don’t you think the age of voting should be lowered?’ asked one of my students.

‘I am in favour of votes at 16. It would radically alter things at school. If teachers had to respect that pupils had the same vote as they do, it would change a lot. We don’t apply criteria to voting, do we? We don’t have an education test, or a literacy test. You have an inherent right to have some say in the laws you are expected to obey. Why should someone aged 16 obey a law passed by someone he or she didn’t elect and can’t remove and who doesn’t need to listen.’

My students were certainly listening attentively to Tony, judged by the volume of their applause.

‘You like to encourage people a lot, Mr, Benn.’

‘If you encourage people they do better than if you kick them about and tell them they’ve failed their 11 plus.’

‘You have strong views on a whole range of issues, Mr. Benn. In ‘O Lucky Man’, Sir James Burgess points out: “The dividing line between the House of Lords and Pentonville jail is very, very thin.” You believe the Lords should be abolished, am I right?’

‘The House of Lords, a House based solely on appointment, is the British Outer Mongolia for retired politicians. I also believe we should replace prisons with more enlightened forms of correction.’

‘You came here by bus. You travel second class on trains. Does this mean you think first class should be abolished?’

‘Not at all. I believe second class should be abolished. All people should be treated as first class .’

‘You want to take the U. K. unilaterally out of NATO. You’re opposed to British military action everywhere, especially in Ireland. Your support for Sinn Fein and a united Ireland is not very fashionable. How can peace come to Ireland?’

‘In the end, we only make peace when the real representatives of both communities have to face each other and hold out their hands. We have to negotiate and talk with Sinn Fein rather than isolate it and ostracise it. Peace is no easy task but it’s really worth working for.’

‘Some would say this is all talk, nothing more.’

‘Although it’s the last place to get the message, Parliament has a lot of influence.

Through talk, we tamed kings, restrained tyrants, averted violent revolution. Harold Macmillan put it very clearly: “Jaw-jaw is better than war-war.’’

‘For someone of such strong views , how does all this go down in your government?

‘As a Minister, it’s not easy to drive forward an individual agenda. My colleagues and I are bound by collective responsibility. I’m often at odds with my party but I keep working to convince members.’

‘How do you go about this with others so pragmatic and focussed on the short run?’

I I say to them “Looking ahead ten years this is what we will have to think about…” so I can open up a whole area. I also tell them ‘I’m getting an awful lot of letters at the moment saying this, that or the other. This encourages a lot of debate within Cabinet.’

‘Some would interpret this as a Cabinet divided, as unstable.’

‘On the whole a government where it is known there is a debate going on is more credible than the pretence of unanimity. The idea that a Cabinet is unanimous on every issue isn’t true and everybody knows it isn’t true. I never mind coming off second best as long as I have a chance to put my case. There’s a credibility about that position.’

‘You’re very independent minded, aren’t you.’

‘In the bible there’s a man called Daniel, and he went into a lion’s den. They said, ‘You’ll be eaten up.’ He wasn’t. Have you heard that story? My father sang to me as a child: ‘Dare to be a Daniel, dare to stand alone, dare to have a purpose firm, dare to make it known. If we are not here to do that, I ask, what are we here for?’

‘Something more than double daring. You like to quote from the Bible, don’t you. Are you religious?

‘I’m a humanist. Christians believe that God created man, and humanists believe that man invented God. But whichever way you look at it, we’re brothers and sisters. My mother was a Bible scholar. I think that the moral basis of the teachings of Jesus – ‘Love thy neighbour’ – is the basis of it all. Am I my brother’s keeper? An injury to others is an injury to all. You do not cross a picket line; and that comes from the book of Genesis and not the Kremlin. I was brought up on the Bible, that it’s story was the conflict between the kings who had power, and the prophets who preached righteousness. And I was taught to believe in the prophets.’

‘The prophets always get trounced by those with profits. The story of socialism is one of constant defeat—.’

‘The story of my life.’

So shouldn’t you change your fundamental views when you’re defeated on things?’

‘I dare say that the General Secretary of the Scribes and Pharisees announced in Jerusalem in AD 32, “What’s the point of following a leader who gets crucified?’ And you can say the same thing about the story of power based on greed.

It has always been challenged and comes unstuck in the end. The Establishment can be worn down if you don’t give up. The thing is, if you hold a belief, you don’t give it up because you’re defeated. You have a bounden duty to say what you mean, mean what you say, do what you say you’ll do, and if you don’t win, well then you go on. You don’t say, ‘Oh well! It shows the whole thing’s a disaster.’ It’s getting to the point where everything aspirants for office believe in has been abandoned in the hope of getting office. And when they’ve got office, they haven’t got real power. It’s power without glory.’

‘Some polls say policies such as yours have little public support.’

“I’m not interested in the ticker of fickle electoral opinion. I didn’t enter the Labour Party years ago to have our manifesto written by Dr Gallup’.

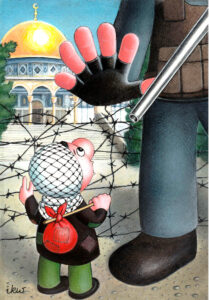

‘It is said you’ve had a number of conversions on the road to Damascus. Someone said you’ve had more than a Syrian long-distance lorry driver. You were were born into privilege yet you fought to cast off those your background provided you with. You fought enthusiastically in the war yet now you’re fighting against current wars. You didn’t question your party’s legislation, ‘In Place of Strife’, designed to curb union demands. And now look at you. You were all in favour of a Jewish homeland when you were in Palestine at the end of the war, but now are a strong critic of Zionism.

‘Would you stick to your guns on your present demands?’

‘My thinking has always been evolving. I must acknowledge I’ve made mistakes. Anyone who looks carefully at my life’s timeline will observe a steady reasoned shift towards socialism. This is my belief and it’s unshakeable. The older I get, the more idealistic I’ve become. Now I know what the world is like, I realise the importance of having a dream.

Now you can just as easily say it’s British politics rather than me that has changed, turning gradually rightwards. Those who maintain the same views throughout their lives without consideration of the need to adapt to changing circumstances, to help others, cannot bring progress. Our nation is in a deep crisis. We always pay a heavy political price when we play down our criticism of capitalism and soft-peddle our advocacy of socialism.’

‘But isn’t socialism just a polite version of communism?

‘‘Oh, that’s just the media. The two attempts at socialism in my lifetime are going to the devil because the communists aren’t democratic, and the social democrats adopt capitalism.’

‘The rich and powerful are not going to put up with what they see as your interference, surely? As shares plunge, many is the industrialist who fears a tax on wealth and expropriation. They say you are a menace. That you get your orders straight from Moscow.’

‘They would say that, wouldn’t they. I think you should always be suspicious of those with power and those who want it. I don’t mean cynical, but someone who has power is someone you have to watch carefully. Corporate influence should be kept in check. Power and the powerful should be held to account. If you meet a powerful person, the key questions you should ask ask them are ‘What power have you got? Where did you get it from? Who elected you? In whose interests do you exercise it? To whom are you accountable? And how can I vote to remove you from office.’ If you cannot get rid of the people who govern you, you do not live in a democratic system.”

‘How do you connect democracy to the the human race, Mr. Benn?’

‘The human race are like survivors in a life boat with one loaf of bread. There are only three ways of distributing it: – you sell it so the rich gobble it up, you fight for it so the strong get it all, or you share it. That is the choice we have to make and that can only really be done in a democratic world, and that’s why democracy is worth working for.’

‘You’ve become a target for some really bad press. It says you’re a wild revolutionary out to wreck the system.’

‘I’ve long been an Aunt Sally for the right. A handy hate figure. If I rescued a child from drowning, the press would no doubt headline the story: ‘Benn grabs child”. I’m actually a traditionalist. But of a different tradition to them. Not the tradition of bowing and scraping to somebody better than yourself but the tradition of fighting for human rights and democracy and freedom and internationalism.’

‘Is there a chance of a Chile type backlash in this country? Could we have a Brutish ruling class ?’

‘I am not impressed with comparisons with other countries. We want peaceful change. The reforms we are pursuing are broadly within the framework of British socialism. It goes right back to the Old Testament. I am under no illusions. I am aware that it is the big battalions in the City, In industry and in Fleet Street who have the power.’

‘And if they feel threatened by too much social protesting to deal with, this could spur elites within the state apparatus to coordinate a coup.’

‘We can never rule that out.’

‘In the past you have said that unless Britain’s political system was changed, public discontent could, and I quote ‘engulf us in bloodshed’. Is this prospect getting closer?

‘All movements for democratic reform challenge the existing power structures. The prospect of peaceful change might be cut off. I have said in the past that democracy hangs by a gossamer thread.’

‘And it broke in Germany after the big slump.’

‘The effect of a slump is not only economic but political. It produced Mosley in the thirties – I had tea in his house at the age of three in 1928. The next time I saw him he was in a black shirt in Parliament Square.’

‘Yet you’re very confident this won’t happened again . That we can create a better world. Are you really confident we can construct ‘a new Jerusalem in England’s green and pleasant land?’

‘I hope so. And we can. I have always tried to be optimistic, because optimism is, I believe, the fuel of progress. Cynicism is encouraged by those who don’t want anything to happen or to ever change. If you can persuade people that whoever they vote for doesn’t matter then that discourages them from making progress. You have to keep hope alive. And I have drawn comfort from looking at historical examples of how we have got rid of slavery, how women got the vote and how it was all achieved when people organised and campaigned.’

When it came to talking about his ideas and history, Tony spoke speak directly to us with an increasing religious fervour. A romanticism ran through his politics like a thick seam of coal through a Lancashire hillside. It now became more pronounced . Drawing deeply from British history, he showed an understanding of it’s broad sweep. His radicalism was of a peculiarly English kind, in that it was also conservative and looking to the past. His idea of nostalgia wasn’t what it used to be.. It doesn’t cling to red phone boxes, red double decker buses and bobbies in blue ;it doesn’t long for a return to railway-cuttings smothered in wild flowers, hay carts and hymn singing.

It appeals to an ‘Ancient Constitution’ established to conserve the rights of ‘free born Englishmen’, setting out the parameters with which to control a king. It appeals to the Common Law, precedent, Parliament, the individual. Tony outlined how today’s parliamentary democracy is a product of the Peasants’ Revolt, the English civil war, the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the Great Reform Act of 1832, the Chartists and radical movements of the 19th and 20th centuries such as the Suffragettes.

‘We have a tradition that can be traced back through the trade union pioneers, back through the Chartists, back through Wilkes and Paine to the radical movements that emerged from the upheavals of the seventeenth century. I’m studying keenly the 17th-century revolutionaries like the Levellers and Diggers, who demanded common ownership of the land. They lived the socialist ethos: ‘From each according to his ability, to each according to his need’. I admire them for their opposition to prelates and princes, for their egalitarianism and for their faith in the common man. I admire them for their commitment, remarkable in its time, to a universal franchise’

He was a fine speaker, able to draw and hold his audience. His was a master class in British politics and history for all of us present. I have never ever heard someone so able to explain complex concepts to young people. My students hung on his every word, and his use of language was so clear and concise that they remembered most of what he said later. This wasn’t as remarkable as it sounds. Like Tony himself, they’d carried their little tape recorders along with them.

When he’d finished there was a short silence as those in the audience caught each others’ eyes, then clapped their hands loudly in appreciation. Next minute, he was away from from the lectern and talking to people as if they’d known each other all their lives.

In a world of politics that is often too small, he thought big about their country and our world.

My students found themselves being being carried along on this wave of logical argument about the case for socialism. What I will always remember, and I’m sure they remember also, is that this educator spoke to us all with the same respect as he would have done to a fellow MP . He didn’t patronise us or talk down. He didn’t use soundbites. He listened to us and we to him.

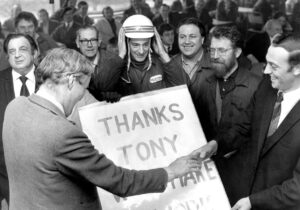

Pulling a black pouch filled with tobacco out of his pocket, he took some out to re-fill his bowl. He then posed for a photograph before pacing back to the Houses of Parliament, sempiternal pipe in mouth.

Subsequently he steered through the public ownership of shipbuilding and aircraft manufacture. In a bid to keep struggling firms afloat, he advocated government funds for co-operatives such as at that of Meriden motorcycles.

On one occasion Tony turned up unexpectedly and worked through the night with them on a new design. Meriden continued to produce Triumph motorcycles for another decade.

Tony endorsed the workers plans for industrial reconversion at Lucan Aerospace in Coventry devised by local shop stewards: The vision splendid of the plan was to replace weapons manufacture with the development of socially useful goods, like solar heating equipment, artificial kidneys, and systems for intermodal transportation. The goal was to not simply retain jobs, but to design the work so that the workers would be motivated by the social value of their activities.

Harold Wilson’s response was to demote him to the position of Secretary of State for Energy , a job where his left-wing, pro-union activities were less noticeable. Nevertheless, he launched the B. N. O. C., a state-owned enterprise, to ensure that the country would derive maximum benefit from the development of new oilfields.

Fast forward a decade, the Labour Government would be defeated, and Tony would hand in the seals of office. The Queen would make a comment to him, the kind she usually made when a resigning minister had just come in. She would say he must be relieved from the strains of office. Benn would tell her, ‘Whereas 25 years ago, we were an empire, now we are a colony, with the IMF running our financial affairs, and the Common Market Commission running our legislation, and NATO running our armed forces.” He would say, ‘The Queen quickly changed the subject!’

Mrs. Thatcher would set to breaking up the old centre-left consensus, based on an all-party commitment to welfare and full employment.

Behind a façade of military and national fervour, she would declare total war on the trade unions and local and regional self government. She would then say to people in effect, ‘You don’t need a wage claim- borrow. If you can’t buy or rent a home, there’s always a cardboard box.

Preferring the country to rely on a service-based, bonus culture, debt-fuelled economy, the complete extortion which is the private electricity and gas markets, and rail racketeering. She would further privatise public assets relentlessly and delivered Britain’s energy resources into a foreign energy cartel. The single European market for goods and services. ensured that a solitary competition regulator based in the EU corridors of power would be the ultimate judge over British business. The French proved the most adept at lobbying this organization. One example of the result is that the nationalised Electricité de France is protected from competition at home but meanwhile can borrow money at low government interest rates and expand with impunity in the open door of the British energy market. British taxpayers would have to to bail out the banks in concert with taxpayers of other nations throughout the globe.

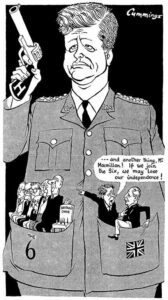

Mrs. Thatcher would tear into the policies which Benn argued for. While this was happening the press behind her would have their knives out for him personally, calling him ‘loony, dangerous, a couch case crackpot-Bogey Benn’. And that was just in the sporting pages. ‘The Sun’ would suggest he was perhaps “the most dangerous man in Britain”. Delegates to Conservative conferences would display ‘Ban the Benn’ badges in the style of CND’s ‘Ban the Bomb’ logo. Some cartoonist’s would even draw his eyes as little spirals to ensure that demonic look.

The big miners’ strike of 1984-85 would see Tony at his finest, tirelessly travelling the country supporting picket lines, urging consideration of a general strike in support of the miners.

He would manage to unite inner-city struggles with the mining communities and always bringing a strength of internationalism into all of his speeches, regardless of the fact that it might be at 5am on a freezing picket line with an enormous menacing police presence threatening the miners and their families.

After the National Union of Miners was defeated he would introduce the Miners’ Amnesty (General Pardon) Bill 1985 to the House of Commons which would secure an amnesty for all miners imprisoned during the strike.

There is no moral difference between a stealth bomber and a suicide bomber. Both kill innocent people for political reasons.

Tony Benn.

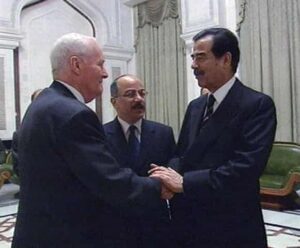

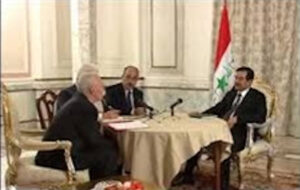

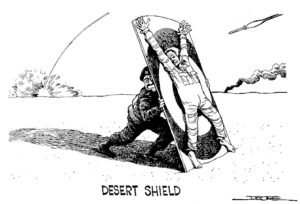

Before the outbreak of the Gulf war in 1991 he would go to Baghdad.

The aim would be to try to obtain some kind of agreement.

He would gain the release of hundreds of hostages held as human shields.

He would memorably say when the war started that George Bush Snr had declared himself at war with humanity.

He gave an impassioned speech to the crowd at the anti-war protest in Trafalgar Square in September 2003.

In returning to Baghdad to argue against further war he would sum up his mission thus: “Do we want to tear up the charter of the United Nations so painfully and lovingly constructed after the last world war that says, ‘we, the people of the United Nations, determined to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war which, twice in our lifetime, has caused untold suffering to mankind’?”

In an age of spin, he was like Mrs. Thatcher: solid, a signpost and not a weather-vane. But pointing in a totally different direction. While she led straight ahead from the front, he guided, carried, and shepherded.

Having won 16 of 17 elections fought, Labour’s longest-serving MP would retire from the House of Commons in 2001, to “devote more time to politics.” He would never make it to No. 10.

However he had “made the weather”, in the sense that he set the agenda for the politics of his day. He rose almost to the top in politics, but he was not like some who reach the top and then pull the ladder up behind them. Wrong by wrong. He looked down and beckoned others up.

Tony Blair’s ‘New Labour’, a complete repudiation of Tony’s ideas despatching Clause Four down the memory hole, would leadl him out of Parliament and on to the streets to campaign for socialism. Eloquent as ever through pipe, megaphone or microphone .

He understood there’s never a final victory for democracy. It’s always a struggle in every generation and people have to take up the cause time and time and time again. It’s easy for socialists to propose. Another thing for them to dispose. As Tony was seen less on the nation’s TV screens he was seen more at protests, rallies and campaign meetings.

To many he was a voice of inspiration, ranging widely, from the global politics of the Arab street to that of your local estate. With his warnings against globalisation, corporate power and American adventurism, he was a Cassandra for our times.

His death was followed by praise coming his way, much from former enemies. A truckload of it. They looked back on him as a curio, an ornament of British life.

Hailing him as heir to a long tradition of English dissenting radicalism, admitting him to that small pantheon of national treasures whose past sins are forgiven. Following the Queen’s approval his body rested in a chapel in the Palace of Westminster, the same one where Margaret Thatcher’s lay before her funeral.

“It’s the same each time with progress. First they ignore you, then they say you’re mad, then dangerous, then there’s a pause and then you can’t find anyone who disagrees with you.”

Tony Benn’

‘During the lifetime of great revolutionaries, the oppressing classes constantly hounded them, received their theories with the most savage malice, the most furious hatred and the most unscrupulous campaigns of lies and slander. After their death, attempts are made to convert them into harmless icons, to canonize them, so to say, and to hallow their names to a certain extent for the “consolation” of the oppressed classes and with the object of duping the latter, while at the same time robbing the revolutionary theory of its substance, blunting its revolutionary edge and vulgarizing it.’

Lenin, ‘State and Revolution’

As for bringing this history to life, the textbooks were rather lacklustre. Chalk and talk could only take me so far. Sir Mortimer rode to my rescue to rally enthusiasm for the subject. Recordings of his television programs offered a spirited account of life in earlier times.

Throughout our journey in time, I reminded my students to keep uppermost in their mind one main question “How did such a small country as England became so powerful a force in world history, out of proportion to its size and population?”.

Our study was concerned with the lives of the men and women who contributed to this history, for good or for ill, the growth of England’s political institutions, the Kings, Queens, the common people, those men and women who fought against the establishment, whose revolutionary ideas helped change the face of government, brought down kings and parliaments and struggled for an end to foreign occupation and for greater democracy. Not the spectator politics of an anaemic democracy, where it’s all the sound bite, fortune cookie media grab of the spin doctor on the telly and people sit at home and watch it. Democracy being what people do, not what is done to them.

I related these people and events to those they were familiar with. I invited them to see the struggle of their Caribbean forebears against colonial rule and for independence as a process similar to those that were going over the millennia from John o’ Groats to Lands End under various occupations. Their response was that the overriding question I raised with respect to England could equally be raised, by analogy, with respect to Cuba.

I encouraged them to see that the West Indian immigrants were merely the latest of a succession of newcomers who brought their own identity to this sceptred isle.

‘They’ve all ended up adding to that melting pot, ’I said.

‘Yeah, and the people at the bottom get burned while all the scum floats to the top’, was one cynical response.’

I challenged these young black British to see their engagement in studying the ethnic origins of white British as just as vital as their parents interest in tracing their own roots – that it would help in their own empowerment. They would be tracing an offshoot of their own race –the human race that emerged as the Leakeys revealed-in days of yore, in Mother Africa.

I worked to inculcate in them a questioning approach – for them not to take the actors in the English annals at face value, not to accept uncritically what they said was their motivation, but to penetrate below the surface to find the reality.

Just as the English landscape has been a moving battleground over which armies have ranged throughout the centuries, so too is the historical interpretation of this fighting. In seeking explanations for historical events and developments, I explained to my students that historians, have strong disagreements about explaining events and that these differences can be related to their differences over contemporary matters, and that the interpretations can see-saw, finding more favour in some times than in others.

I gave my overall view of history as being an ongoing struggle between different social forces for control of resources and technology, and for political power.

One of the greatest polemical issues over which English historians have argued is one which I had to bring to my students attention – the period from 1640 to 1660. This was the only time when England was a republic and underwent profound political vicissitudes, including the execution of the king. I posed to my students a number of questions. Why did this happen? What was it all about? What significance did it have for the here and now? What did it say about the English character if there is such a thing? What did it have to do with them and their lives?

Conservative historians tend to pass lightly over the bloodshed and violence that accompanied this period as a rebellion, the ill consequence of courtly intrigue, seeing the events as a blip on the historical radar. They saw it as a fluke, something that never made sense, a regrettable aberration from the normal reasonableness of level headed Englishmen who descended to the same level as their hot headed continental neighbours – or indeed their “empty-headed” Afro-Caribbean protégés – in fighting one another about politics.

I presented the English Revolution as an event as momentous as its French and Russian equivalents, each having parallels in and differences with the others. It was in England that the epochal conflict between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, representing the feudal and capitalist systems came to a head. It was there that the middle class based on trading and industry grew in wealth and strength. This was a class war in which Parliament overthrew the despotism of the King, defended by the reactionary forces of the established Church and the conservative landlords. It was able to appeal to the enthusiastic support of merchants, small holding farmers, and enlightened gentry and to wider masses of the population.

Parliament emerged triumphant to change the structure of politics and society so as to serve its interests. Its victory cleared the way for the capitalist development that made it possible for England to become the country of the first industrial revolution. One that enabled Britain to become the world’s premier economic power, dominating world trade and finance. The markets, sources of food and raw materials and targets for overseas investments came with the world’s largest empire, central to it’s image and prestige. This revolution would play out on a global scale changing the lives of my students forebears in the West Indies and in Africa as profoundly as it did the lives of the English, the Irish and Australia’s aborigines.

I stressed that in this profound political upheaval the poorest mattered collectively for a season as much as the greatest. From the raucous streets of London and the clattering printers’ workshops that stoked the uprising, to the rank and file of the New Model Army, they were crucial to the success of the Parliamentary forces. The vacuum created by the loss of control by the Royalists led to the flourishing of self governing bodies of workers and farmers struggling to make themselves and their world. A world that Winstanley declared would be ‘a common store for all’ At key turning points in this period it was popular activity of the masses that shaped events. The Levellers and Diggers gave a try at leading the revolution in a more democratic socialist direction, to end the ages of necessity and open a new millennium of universal human freedom and sovereignty.

All kinds of free thinkers, utopian dreamers of all creeds, surged hither and yon shouting their heads off in the greatest outburst of popular idealism England had ever known. As with the rastafarian revolution promulgated by Jimmy and Bob, the ideas being thrown about like confetti were couched in puritanical religious terms . The question of the conditions of entry to the paradise hereafter and to any promised land that might arise on this earth was hotly debated.

As in all these revolutions such free minded activity was at fearful odds with the self appointed gatekeepers who would dictate the conditions. They would decide, especially with respect to the secular paradise, the one point of entry. The big end of town. The victory of Cromwell over the Royalists and then over the populist elements of the Revolution accelerated the enclosure movement denying the poorer peasantry and artisans access to common land for fuel and pasture for their few animals. This access had enabled them to supplement their precarious wages. ‘A bit on the side’ to put it simply. Enclosures approved by the Parliament meant the dividing of lands which had been at the disposal of the whole community into private properties. The victory led to the military campaign against the Irish, the expansion of England’s colonial possessions and the trade in slavery.

My students became very attentive when I informed them that roughly 12, 000 Irish were sold into slavery at this time. I asked them, “What do you think Africans feel like when they find this out”.

“Like toasted Irish” one boy shot back incisively. ‘On the same signs as my lot : ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs’. So if you were a black Irish wolfhound you had no chance’.

All the consequences of Parliament’s victory favoured the privatization and accumulation of capital and a climate in which technical breakthroughs would find wealthy backers. The subsequent return of the monarch would not change the profound transformation that had occurred in England, that ‘teeming womb of privilege’. This was a demystified monarchy aware of its limitations and unable to return to its absolutist ways. Its marriage to the bourgeoisie would create a new mystique that downplayed the import of those days which saw the world turned upside down. Glory days when many ordinary people threatened to take their lives into their own capable hands. The Old Mole of social revolution that keeps creeping out from hibernation after long cold winters. Re-emerging in the sixties and seventies spouting Karl Marx or predicting the end of the end of the world.

Rather the mystifiers’ emphasis would be on the stately continuity of English history where reason and moderation reign supreme, where events such as the student occupations, huge anti war demonstrations and miners strike that had been occurring around England were explained as mere hiccups- temporary lapses from an unbroken sequence- the work of spoilt ungrateful scholars and lazy artisans, greedy of gain. These appeared to be ghosts of the forward looking educated class and plebeian elements from the Revolution whose role likewise would have to be played down in the pages of history.