I got around London admirably by red bus and the London Underground.

I found a bus to be a vehicle that runs faster when you run after it and runs slowly when you are inside it. So at least to avoid any unnecessary running, I just crossed in front of each one on the road and darted around the side as it halted so as to jump on the open platform.

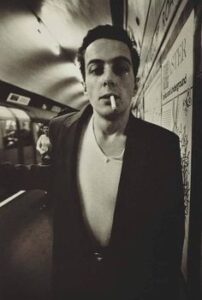

As I travelled the length and breadth of the Tube, I became familiar with the gruff, rasping voice. The Tube was my main means as a peripatetic pedagogue of getting to and from work, but for John ‘Woody’ Mellor the station at Green Park was his workplace.

Not that he worked for the railway unlike his grandparents who were officials in India’s vast and complex colonial railway system. The underground rail system of London was the stage for this natural born freewheeling jongleur. A stage where this protesting voice of London’s underground culture railed against the values and practices of manufactured society in a most pleasing way.

His was a welcome presence. He played much better than most.

While his ability on the guitar still lacked refinement, he had a knack for holding an audience by dint of his emotional intensity and engaging manner. Appealing to our longing for a moment of spontaneity in our city-structured lives, he could always count on drawing a decent size who listened with rapt attention. He chose from a diverse repertoire of pieces that would put an extra spring in my step or help me unwind and reflect at the end of a long day. Being of a gregarious disposition, he was always happy to discuss his performance and views after he was done with. Noticing that he had a liking for songs with Spanish words, I tried getting through to him in Spanglish. ‘Que buscas?’ I asked him, throwing some coins into his case, using the word from which busker is derived. ‘What are you looking for?’

‘That’s what many of my audience ask me. I tell them I just want decent digs.’

‘And beyond that?’

‘I want to occupy a more exalted “estacion en la vida” -station in life – I want to make my mark on rock music!’

‘ Your name in lights. That’s the ticket, ’I said. ‘Who’s your biggest musical hero.’

‘My name gives that away’, he replied. ‘Woody Guthrie, someone who was of great, great importance to me.

He wrote songs of hope, feel good songs celebrating life and self-pride. No wallowing in self- indulgence. Woody first made money with his musical ability–singing, dancing, and playing the harmonica and spoons on the street for change. He spawned hundreds of songs about migrant workers, demonstrating a deep love for them and the lands they travelled. He was particularly concerned about the hostility towards so called ‘illegals’, specifically Chicanos, by locals and the naked exploitation that they suffered. He wanted to do something about such travesties of justice .’

John chose regular spots to play at which he maintained his presence.

As well he performed aboard the trains to and from the stations.

‘Playing on board means you have a captive audience,’ he said. ‘The drawback is there are other operators working the lines too.’

Where has been your favourite spot to busk?’ I asked him.

‘That would have to be at the seaside on the esplanade. People are in a relaxed, happy mood. Therefore generous.

Plus there’s always ice cream available to help you cool down.’

Busking either solo or with a violinist rejoicing in the name of Tymon Dogg, John got to choose his pitch carefully so as to catch the greatest number of ears and escape the clutches of the authorities. He showed me some of the pitfalls when we were heading to the platforms after one of his performances.

‘See that sign up there. ‘No Busking allowed. By order.’ ‘For crying out loud !The only orders I listen to are last orders, know what I mean.’

“See those speakers up there”, he said pointing to the fixtures on the Tube’s walls, “They’re hooked up directly to the transport police. You might call it music to their ears …. but not the stuff they’re into. The clanging of coins into their coffers when they fine you. Colonel Bogey for young fogeys. Just ‘cos we jolly people up . Big Brother and the Holding Company I call them.”

‘You should be able to play wherever you want’. I said parenthetically with my tongue in my cheek, ‘It’s a free country. As long as you don’t block the passageways, no one should mind.’

’‘All the laws are against us. Whoever’s got the money’s got the power. They’re free to interpret the regulations. Like squatting busking is a grey legal area we inhabit. They can charge us with vagrancy or soliciting. If they want to bust us they’ll invent some reason.’

We were both heading to Notting Hill and decided to travel together. ‘I’ve just got to check my map. Wait a minute while I get a ticket, I said. ‘What about you?’

‘Don’t worry. We don’t need one. I know the best way there. Just stick close to me.’

‘Take me right back to the track, Jack!’

’As we approached the platforms he elaborated on this Orwellian theme: “The way I see things, Big Brother is watching everything we do – trying to snaffle everything”.

‘Have you ever thought how much the iron horse is a presence in music ?’he said as we waited ours. ‘It can be a symbol of freedom or lack of it. It can be a vehicle of reunion with or abandonment with a loved one. You can hear it’s whistle in music’, he said, producing one on his string. You can hear it’s rhythm.’

‘You can hear it in ‘The Rock Island Line’. The song picks up speed as does the freight train’.

‘You know how Johnny got to B Goode?’ he said, as a train clicked past. ‘Like Chuck Berry himself, Johnny sat out by the railway tracks learning to play his guitar along to the rhythm the train made. Boom chick a boom. Boom chick a boom.

And then there’s rakes and rakes of trains running through lyrics. Take those of Curtis.’

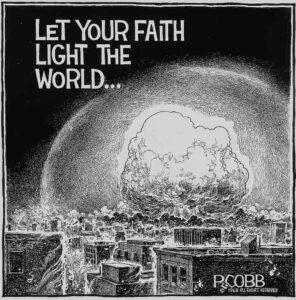

‘People get ready,’ he sang aloud as the platform filled up, ‘there’s a train comin’,you don’t need no baggage, just get on board, all you need is faith to hear the diesels hummin’, you don’t need no ticket, just thank the lord. Faith is the key, open the doors and board them, there’s hope for all among those loved the most.’

Once we were rolling along the rails, I added, ‘People need to have faith in each other. Like the Temptations urge , we’ve got to learn to live with each other. No matter what the race, creed or colour, we’ve got to board the Friendship Train.’

Roaring along through the sooty bowels of London I was intrigued by my well spoken fellow traveller’s accent. Without sounding put on, he seemed to be cultivating the dialect of those native to the more proletarian end of town. Like Woody who had employed a theatrical Okie drawl to disarming effect , he wanted people to think of him as an honest to goodness working class person, not an intellectual. Someone who listens to the William Tell Overture and talks of the Lone Ranger rather than opera. ‘No wonder I think like a Digger,’ he said, referring to the socialist element of the English Revolution. ‘I dug graves a while in Wales.’

‘Now there’s a job in which some can happily work for others.’’

”It’s the only job I’ve had where I started at the top. Then I got the kiss off. They found me asleep in a grave.’

When speaking, It was as if he had been studying elocution under both Eliza Doolittle and Professor Higgins. To test him, I put on my interpretation of Peter Sellers’ posh voiced journalist interviewing Tommy Iron, the jumped up rock and roll star from the East End.

“Do you find it’s a hindrance, this guitar for you?”

“I wouldn’t say that”, replied John without hesitation. taking off Peter’s Cockney character spot on. “I can’t sort of bite the hand that fed me, or the fret board that fred me, to coin a phrase. I’m jolly grateful for what it’s done for me. It’s brought up to where I am today….”. “Actually, Old Bean’, this mockney said, affecting now an exaggerated plum in the mouth, ‘last gasp of the Raj’ tone, ‘it was a darned hindrance when I was playing at the National Opera. By jove, it was”. And then reverting to Tommy Iron’s voice “The guvnor caught me red handed noodling in the orchestra pit. Was ‘e narked”.

“ ‘ I say, what’s all this little lot ?’ Lord Muck demanded”.

“O Sole Mio” I replied, “Caruso’s Neopolitan ballad” .

“By gad you’re supposed to be scrubbing the floor, not naffing about,” barked the boss. ‘Let me remind you ,you’re on the clock.’

Like myself John had used stints employed as a general dog’s body to clean up his own act. While respectful of those who had to do such work day in, day out, he saw it for him as just one more dead-end menial job that he had to grub away at.

“Not to worry boss, I’ll catch up tomorrow”.

To which Mr Smartypants replied “ Listen up, pack your gear up now. There’s no time to sleep on it. There’s No Tomorrow”, quoting the version of the ballad that Elvis cut in his German home. ‘You don’t like our rules, there’s the door!’

‘Can you hear that?’ I came back, happy for an out, ‘that’s me, whistling in the street. Seeing this as the opportunity to get right into my own music, even if only busking, I was glad to give up my day job and pack in this soap opera. I might be a nobody but I’m nobody else’s nobody.’

‘I’m a nobody too, but don’t forget. Nobody’s perfect. So we must be too. I take it you didn’t qualify for the Employee of the Month Award.’

‘I’m afraid I missed the unique chance. To be both a winner and a loser at the same time.’

‘Were you punctual?

‘If I wasn’t I’d always offset any loss. I always arrived late , but I made up for it by leaving early.’

‘I take it your heart wasn’t in such low paid, fitful work.’

‘I pretended to work as long as they pretended to pay me. I turned it into an art form.’

‘Oh well, at least it sounds classier to be an unemployed musician than an unemployed cleaner.’

As does it sound classier to be a ‘pick up artist’ than a ‘garbageman’. Or a sign painter than a carpet cutter.’

‘You did those jobs?’

‘I got a job in an Allied Carpets warehouse as a sign painter until Walter, the foreman, brushed me aside. H wanted to know if I’d be permanent. I said, You must be joking, there’s no art involved here in which I’ll stand out. As soon as I said that I was back on the carpet cutting floor.’

‘Did you stand out there?’

‘Only when I tried to go undercover. After that it was goodbye to cutting, goodbye to Walter Wall.’

‘Are there any casual jobs you wouldn’t mind doing?’

‘Inspecting mirrors I could really see myself doing that.’

Doing temporary jobs enables you to get jobs without employers demanding an extensive resume, wouldn’t you agree?’

Sure,l ike the job I picked up in the information booth at Cruft’s Dog Show. No questions asked.’

‘What other memorable jobs have you done?’

‘I was willing to try anything to keep body and soul together humping crappy jobs on the night shift. Skivvying around double bubble. I had a stint at digging graves. We could make as much loud sound as we liked without being bothered.

’Enough to raise the dead?’

‘We couldn’t raise them but we helped lower them.’

‘It sounds like a dead end job.’

‘I thought of opening my own business with the pitch, ‘Why go on living when we can bury you for twenty five pounds.’

‘After that?’

After leaving the cemetery I wanted to keep outdoors so I worked in the forest as a lumberjack.’

You got tired of that?’

‘ I just couldn’t hack it, so I got the axe rather than the axminster. I had a job drilling holes for water – it was well– boring. Then i went for easier stuff. I tried out as a doorman but kept getting arrested for loitering. Then I tried my hand as a trapeze artist for all of five days, but I was let go. I used to work in a sports store selling trampolines- on and off. I used to sell loose potatoes. That’s til I got the sack. Then I got two jobs that bored me witless. I had a job at an orange juice factory. I got fired because I couldn’t concentrate.

I worked at the bank as a teller for a while…until I starting losing interest.

‘You didn’t need much encouragement to leave.’

‘The moment the bank manager told me, ‘Morning, it’s a nice day for it!’ , I went home.

‘Many people deliver junk mail. Did you ever try that?’

‘I used to be a flyer distributor. Yeah, I remember that day. I was supposed to go to 2, 000 houses. Or three skips.’

‘All in a day’s shirk. Any memorable jobs you found too daunting?’

‘Selling doors, door to door.’

‘That sounds like some heavy lifting.’

‘As well as some effort crafting my pitch and sweet talking. I felt highly obligated but was glad to be taken on.

The firm’s management put enormous pressure on us salesmen to produce or to lose their jobs. To motivate our team they offered us prizes for the most successful salesman.’

‘Did you win the contest?’

‘I was awarded third prize.’

‘That sounds all right. Did you get a promotion?’

‘To answer that, let me just tell you how the sales manager outlined to us the way they ranked the competition: ‘As you all know, first prize is a full expenses paid holiday on the Costa Brava. Does anyone want to see the second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is a letter of certification as to your company status. You’ll get the picture.’

‘And you did?’

‘I got the picture and it wasn’t very pretty.

After that I had a stint as a motorcycle courier. Wow, those things are also heavy! For a while I sold furniture for a living… the trouble was, it was my own. I had a brief dose of maintaining swimming pools but at the end of the day always felt drained. I had a job in a stationery factory producing calendars. I was relieved of my duties. All I did was take a day off.

London University medical research recruited me in the pollen count, now that’s a difficult job. Especially when you’ve got hay fever. I worked there on research in the entomology department. They were pleased with my effort. I boxed all the right ticks. I worked in the physics department on a research project to develop a cold air balloon’

‘How did that go?’

‘ It never really took off. That led me to working in helium gas storage but couldn’t take the tone in which I was spoken to.’

‘Couldn’t you have argued within your rights to be treated more respectfully?’

‘The foreman said he’d consider raising the company’s tone. However when a person tells you, ‘I’ll think it over and let you know” — you know.’

‘Do you have any regrets about these casual jobs?’

‘As I get older and remember all the people I lost along the way. I think to myself maybe my stint as a tour guide wasn’t for me.’

‘Were there any jobs you refused point blank?’

I turned down a job trying out toys. The manufacturer of those foolproof items keeps a fool or two on their payroll to test things.’

‘You had a real ragbag of odd jobs. Was there any where you you feel you had a modicum of success?’

‘That was in Sales. Carrying around protective eyewear is much lighter than doors. I succeeded in persuading even blind people they needed sunglasses.’ I succeeded in persuading blind people they needed sunglasses.’

‘Shades of Ray Charles! You must be anxious to get involved in a band where you can come into your own.’

‘I’m open to all kinds of offers.’

‘Now tell me how about your own sound, there’s a good chap.’

With this John played for me some bars from Elvis’ rewritten version, that which he had been practising “Its Now or Never”.

‘It’s very stuffy in here, ’I said, ‘can we open the window now?’ I said, ‘or is it never allowed?’

‘These trains stir up a lot of dust in the tunnels. If you were to open windows, you’d cop a faceful of soot and god knows what else in your face. Being air-conditioned, the windows can now only be opened by members of staff. Only in case of equipment failure. I was told at my grandfather’s knee the perils lurking outside train windows.’

‘There are signs elsewhere on the rail grid warning you ‘Do not lean out of the window!’

‘‘For good reason. During the General Strike of 1926 the fascists served as scabs on the railways as elsewhere. Through this they acquired a martyr. One of these unthinking young crims leant too far out of a window and was struck by by a bridge.’

‘A bridge too far. The way I heard it that once off rail worker had just his elbow sticking out. When his commanding officer warned him ‘Look out!’ he obeyed without hesitation. That would have given him a splitting headache.’

‘It had no time to ache. He was decapitated.’

On our journey the train broke down in the middle of a tunnel. It was at a standstill for three hours. An official came through the carriages apologizing for the delay. ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, on behalf of London Underground, I’d like to apologise for this standstill. A fractured air pipe has caused the brakes to lock. There is no danger and we’ll get you moving again as soon as humanly possible.’

A party spirit and togetherness caught us when I least expected it. With me, the antipodean Temptation out of retirement as back up,Joe got to work with his guitar singing, ‘ Everybody shake a hand make a friend now

Listen to us now, we’re doing our thing

On the friendship train

We’ve got to start today to make tomorrow

A brighter day for our children

Oh calm down people now we can do it

I can prove it but only if our hearts are willing

Everybody shake a hand make a friend now

Listen to us now, we’re doing our thing

On the friendship train.’

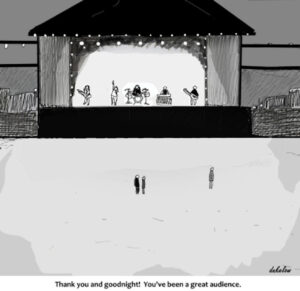

The show had begun. People talked to each other’s children, taking their minds away from the circumstances. One young man improvised a clowning act, doing some particularly nonsensical, preposterous things, then looking into the eyes of a boy, and saying with his eyes, ‘I know you know how silly that was … what a thing!’

That did it. the first laugh popped the tension right out of that carriage. The boy laughed then another child laughed. Each laugh veering from uncontrolled gurgles to raucous barking helped to build the next. We were all in the moment.

‘You’re not a serial killer, are you?one young woman said to the man she sat next to.

‘I’m a biographer, butI have something in common with one.

‘What’s that?’

‘Multiple life sentences.’

One businessman said to another sitting beside him, “We’ve ridden this train every day for some time, but we’ve never talked. You’ve never asked me ‘How’s business?’

‘All right, How is business?’

‘Oh, Don’t ask!”

Then a frail old man improvised a magical show. His clothing seemed to hang on his small frame. Even his voice was too small. And his hands were so gnarled from arthritis it felt a little scary to let him proceed. He appeared to have no idea what he was doing until his turn came Then he knew just what he was doing, and suddenly he turned into a star showman. He took a prop out of his pocket, a hard rubber ball. He straightened himself, extended his arms, and the ball began doing things a ball couldn’t do. Things no magician I’d ever seen could make it do. When he performed, his old gnarled hands became strong and nimble, pulling off tricks that required the dexterity normally associated with twenty-year-olds. As he adjusted his posture, his whole demeanour became youthful. Suddenly, the man fitted the suit. He became ageless. The life of the party. Entertaining so focused him that there was no room for age or ailment, only for performance art and the joy this brought to him and his audience. He engaged the children, asking them if they would like to help –to help hold something, help say the magic word, or help wave the umbrella wand, getting them to push the invisible button on the top of a briefcase, touch their own nose, or stick out their tongue The kids helped by smiling or making funny faces at the moment they saw fit.

Packed into a hot underground train where Brits are normally stony-faced, pissed off and uncommunicative, I found that after these preliminaries, practically everyone had launched into spontaneous entertainment, ludic laughter and conversations about their day. I had assumed that the group I was talking to had all arrived together. I was wrong. They had met just an hour before in the queue for the train. A young couple ate their sandwiches, and I said, after about half an hour, “How long have you been married?”

“Oh, we met on the train!” they said.

A bee hived, bobbed woman said, “Will you get off at Notting Hill Gate and ring my son in Shepherd’s Bush. He will be worried?”

By the time big steel rail carried us to Notting Hill, this train was bound for glory.

Would we all go back to ignoring each other when this was over?

On which note John signalled we’d now go our separate ways .

‘Pip pip, cheerio, dear boy, I’ve got to see a Dogg about a man.’

‘Toodle-oo, the same to you’.

As I left the station, I saw the graffiti on the wall warning ‘Squat Now While Stocks Last. I speculated how great the rush would be. Retailers of portable shelter, cashing in on the housing shortage busily advertised their goods: ‘Now is the season of our discount tents’.

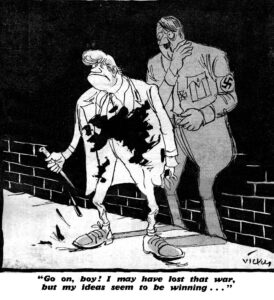

On a shopfront someone had spray painted NF and below this, they drew a swastika. Next to this were a couple of unsuccessful attempts at drawing a swastika. They’d obviously misjudged the complexity of the operation. Rather than spray paint over the failed attempts, they left them there. They must have thought you get some credit for showing your working.

The Angry Young Man

The table was set. Then I arrived. The Notting Hill Gate area which Elgin Avenue in Paddington skirts was home to incendiary street politics and ethnic tension. Under governments balanced on the fragile edge of tolerance nowhere was that edge so sharp as here. One lived one’s youth here, it seemed to me, going from march to march. Thirty years before Hugh Grant made it chic , this was England’s answer to Greenwich Village or Haight-Ashbury. The lively culture and concerns attendant with this milieu was a powerful brew from which I, working on the edge, would quaff deeply. Sharing my cup was John Mellor who I called in on regularly at his squat at 101 Walterton Road, Maida Vale which skirts Notting Hill Gate. This house was just around the corner from the bustle of Elgin Avenue, home of the largest long term occupation by squatters in England. All these residents were members of the Maida Hill Squatters and Tenants Association.

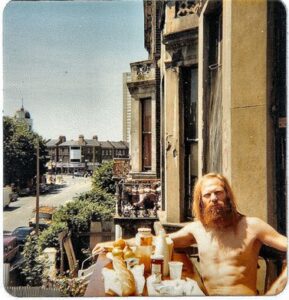

I only popped in briefly to to collect funds, to inform the guys about meetings and actions, but one thing leading to another I ended up getting involved in an on going discussion about the place of music in our lives. He’s seen here on the right having a laugh in another squat a little later.

Like some other squats in this bailiwick away from Elgin Avenue itself, you wouldn’t have guessed the nature of their residence. This anonymity afforded the band John sorted from his housemates the peace and privacy to practice. ‘We wanted a dream squat like Rod Stewart-his had been a houseboat-but this is the next best thing.’

‘Pity you couldn’t have waited a bit longer. We’d got the perfect one for you on our books. The interior guttering is a unique feature, caused by the raging damp. The last occupiers adapted with windscreen wipers for their television set and aqualungs in the bathroom. If the water levels rise the next occupants too will be in a houseboat in a couple of years.’

‘Your’s sounds like Almanac House all over again’, I said, referring to the co-operative household in Greenwich where Woody Guthrie lived.

‘In keeping with our common ideals, we share meals and chores. We have a washing-up rota and a kitty held in a money box. We’re happy to contribute to the squatter’s association.’

This was the action station he was occupying, from whence he hoped to reach the critical stage, bound for glory and prime time.

Like Eric Clapton and Mark Knopfler who would otherwise have been forced into a nine to five existence, he was able this way to make music his priority.

‘Where do you see yourself in five years, John?’

‘Soaring the stratosphere. Part of a great rock and roll act.’

‘Today Maida Vale, tomorrow the world,’ I said. ‘‘Happy Days!’

A tour of inspection of his house had led me to the basement where old mattresses were pinned to the walls for soundproofing.

“Aha!” I cried, “this must be the infamous torture room I’ve heard about”. I had read somewhere in the musical press that his band were named for ‘Room 101’, from George Orwell’s novel 1984, in which the cries of agony were muffled. The novel being something of a manifesto for John, he was tickled pink by this urban myth which he most likely fostered himself and just let ride. When I put this to him he owned up with the more mundane explanation. “Our name came with the house’s number. We can thrash our instruments, jamming hell for leather down here and no one suffers”.

He recorded his songs on a boom box.

‘These devices are so versatile,’ I said.

‘Not only can you receive radio stations and play recorded music, you can record onto cassette tapes yourself and from from radio.’

‘What I would have given to have such a thing back in Blantyre.’

‘And for me back in the bush .

’’Best of all you can move them around. They help me to maintain my regular listeners when I can’t make my usual underground spots.’

‘They help me to maintain my regular listeners when I can’t make my usual spots.’

Over strong cups of char long into the night in his threadbare living room this generous host plied me with whatever snacks he could scrabble up. What he lacked in brie he made up for in brio.

‘What kind of sandwich would you like?’ he asked me. ’We’re fresh out of pate foie de gras and supermarket soul food but we’ve got some lettuce, some humous and some lentils. What would you like?’

‘I’ll have a Zen Special, ’I said.’ Make me one with everything.’

He replied, ‘I’ll have a Karma Butty; I ‘ll get what I deserve.’

‘You don’t deserve to get botulism. Some of your food is way past its sell-by date.

‘Please don’t tell me you subscribe to the “Best Before” conspiracy?’

‘Just look at the label on this can ‘Best before 1969.’

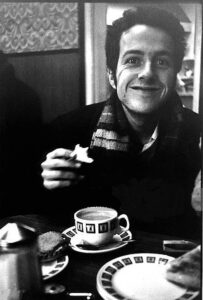

In a local cafe as well as in the squatted community eatery, ‘That Tea Room’ where he often hung out, John and I got on famously discussing the state of the world, our place in it, how best to set it to rights and his overriding passion – music. I enjoyed the humour and insight he brought to bear on all kinds of matters.

One of the appealing things about him was the idea we had in common that what you became and where you are going is more important that where you come from. Not that where he came from wasn’t interesting. “What’s your story, morning glory?”, I asked him in that rapid-fire rhyming jive-talk, so faddish in the fifties.’

‘I’ll give you a clue, Blue’, he shot back. ‘I got around. My father was a diplomat.’

‘That must have a boon for a son. A father who could deal with others in a sensitive and tactful way.’

‘He could tell you to go to blazes in such a way that you would look forward to the trip. He was super strict. I only got to see him twice a year. I could have fitted into the same mould if I had so wished. As a titch, my brother David and I accompanied our parents on their British Foreign Service postings around the world.’

This undoubtedly was what contributed to his sociable nature and to his impeccable manners, as did his acting as a waiter at diplomatic social functions.

‘You remind me of how Peter Ustinov defined a diplomat: A headwaiter who is allowed to sit down occasionally. So when did you finally return to settle in England?’

‘My brother and I returned to England after Malawi, where Dad was posted, obtained its independence from Great Britain.’ We had been consigned early to a boarding school on the outskirts of London.’

‘That must have been a hard decision for your parents to take.’’

‘ It’s easier, isn’t it? It gets kids out the way, doesn’t it? The school had everything to recommend it except pity, where I learned to loathe my own kind.’

‘How come?’ I asked.

‘It was a place to which thick rich people farmed out their thick rich kids. David and I were boarders’, he said, in full flow. I didn’t take well to the experience. You either became a power or you were crushed. Small for my age, I was dumped in a bath full of used toilet paper on my first day. Another time I was bogwashed, dangled by my ankles before being dunked headfirst into the flushing toilet. The harriers who never picked on anyone their size enjoyed dishing it out but it became the bane of our lives.

They called us all kinds of different names. They called my mother names I’d never heard of. But one day I turned to our tormentors and said ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me’, and it worked! From there on it was sticks and stones all the way.

‘It won’t hurt—–much,’ I remember one of them prefacing his assault.

We pleaded with them, ‘Our parents told us not to get into fighting.’

One of the bullies answered, ‘Well, you won’t have to then. We’ll do the inflicting, you’ll just do the hurting.’

‘Why don’t you pick on your own size?’

‘It just happens you’re the only size available. You drew the lucky numbers.’

I threatened to punch one in the head. Instead of him recoiling, he proffered me his head, taunting me, ‘Come on, take a shot. Give me your best. ‘Cos when I get up, I’ll tear you apart.”

‘You’ll pay for this!’ I warned them.’

‘Just send us the bill.’

‘Couldn’t you keep a safe distance from them?’

‘I avoided letting them catch me in the halls alone, on the stairs or especially in the bathrooms if I could help it.’

‘What did you do?’

‘I held it in. I stayed away from liquids but I couldn’t from them. One time I was hunted down and bailed up. These members of the Hitler Youth grabbed hold of my arms and legs and carried me bodily back into a changing room.’

‘Is this going to hurt?’ I asked.

‘No, I won’t feel a thing, ’said their fuhrer. They held me down while one of them filled a bath brimful of icy-cold water, and into this they dropped me, clothes and all, and held me in there for several agonising minutes. ‘Push his head under water!’ they cried. ‘That’ll teach him to keep his yap shut!’

Clenching my throat, turning bright red and making hacking noises, I spluttered and half-drowned,

The fuhrer asked, ‘Are you choking?’

‘I said, ‘No, I’m serious.’

When at last they released me and I crawled out of the bath, I didn’t have any dry clothes to change into. Another time they caught me, put me in a rubbish bin and rolled me across the playground.”

‘And to think your parents paid for the privilege, I hear you cry’.

‘Their imagination was both cruel and comprehensive. They made a sport of us. They blackened my eye, set fire to my tie. I got pushed around, knocked to the ground. I got belted around the ear, swatted on the back of my head with flat hand and knuckles. My ears were twisted, boxed and thickened on many occasions. I was slugged with board rubbers, slippers, rounders bats, flicked with wet twisted towels,given Chinese burns. I was slapped, shaken, half-suffocated, had my hair pulled and thumped in the middle of my back, kicked in my nuts.

‘Kick him in the goolies!’ I’ll always remember the head bully ordering his hesitant underling.’

‘Won’t that hurt too much,’ objected the underling.

‘Not if you’ve got a strong pair of shoes.’

‘Mine weren’t so strong soon after. I came upon them with ciggies in the toilet block. The head bully asked, ‘Do you smoke?’

‘Definitely not,’ I said.

‘Do you wanna bet, ’he said as he set fire to my sneakers.

‘They knew no bounds ,’I commented.

‘Any part of our bodies upon which a black and purple bruise wouldn’t show. Anything at hand could be used as a weapon. They took to us with sticks. I had chalk, blackboard rubbers, plimsolls, ping pong bats-you name it- thrown at me.’

They hit me with a telephone.’

‘You were always on the receiving end. You must have been really cut up about this.’

‘Once I was hit with a camera. I still have flashbacks.’

Were you ever hazed by the older boys?’

‘At the beginning of the school year the senior boys paddled us hard and and sprayed us with tomato sauce, mustard and flour. These plonkers made us swallow oysters tied to dental floss and then pulled them back up. Bizarre!

‘Bullying seemed to be the major sport’, I said, ‘at which you were at the centre, eh what.’

‘Breaking us in became part of every activity. Once at choir practice, a boy clipped me across the ears from behind. I turned around and asked, ‘Why did you do that?’

‘I don’t know,’ he replied, ‘but I’ll think of a reason.’

‘Did you try and get away from him?’

I tried to move away but felt something was holding me back.’

‘What do you think it was?’

‘It was the same boy. He was giving me a wedgie.’

‘What about the day boys?’

‘It was the day pupils who drove into us the finer points of hockey. I was chosen to be one of the heads of the team. As well as bullying off with the ball,” he said, referring to the procedure for starting the game where two players first hit their sticks together, “they bullied off with our heads, good and proper”.

‘The human head is so fragile. It should always be treated with respect.’ ‘Do you think they knew that? The pull-and-choke was also a favourite. It was executed by pulling the compulsory necktie up like a noose, until the face of the boy being picked on turned the school colours.’

‘Did this extend to away games or did they tone it down then?’

‘We once had to play at another school. I was on my way to the oval where we played hockey one afternoon. While walking along the fence of an abandoned vacant lot , I heard the sound of boys inside shouting, ‘5…. 5…. 5’. The tumbledown fence was too high to see over, but I looked through the gaps in the planks to see what was going on.

Some bastard poked me in the eye with a stick.

Then he and others pushed aside the palings to reveal themselves and all started shouting:

‘Then they demanded, pushing and prodding me, ‘Where are you going, Nerd ?’

‘I’m off to the oval. I’m in the team. I’m not looking for any trouble.’

‘Well trouble found you, Nerd, said one. ‘Why don’t you turn around, walk away. Your friends will never know you came this way. See ya, ’he said waving me away.’

‘The team will know. I gave them my word I wouldn’t get into any fights.’

‘Well, they’ll be happy. It won’t be a fight. It’ll be a massacre.’

‘I realised I had to make them laugh or they’d kill me.’

‘Hey Nerd,’ said another, ‘I bet all your friends are nerds too!’

‘That’s where you’re wrong. I have no friends.’

They burst out giggling. By letting them think how clever they were, they laughed it off and let me go.’

‘What do you think motivates their kingpins to act so aggressively?

‘They lead led others to do it because they suffer from delusions of grandeur and are cowards.’

‘Did they ever try and gouge money out of you?’

‘They came to my bed one night and I pretended I was sleeping. ‘Five shillings! Five Shillings’’, one demanded, upping the previous rate. ‘Five shillings! Five Shillings’’

‘Wha-wha-what? What?’

‘Five shillings! The terms of trade have changed. Five shillings.’

‘I heard you the first time.’

“Never mind hearing me. Hand over five shillings.’

‘Listen, five shillings, that’s a very steep price. Could you bring it down a bit?’

‘I’ll bring down hard luck on your head. That’s what I’ll bring down.’

‘Ease off, man,’I said to him. ‘We have no quarrel with each other.’

‘That can be remedied in a walk.’

‘Did they ever do the decent thing?’

‘Once they threw a party for me.’

‘To make up for their mistreating you?’

‘It was a blanket party. They threw a blanket over me in the night, gripped the corners tightly so I couldn’t sit up and to muffle my screams. They beat me with towels slung with soap.’

‘They must have ended up with their lardy arses in a sling .’

‘Not at all. I couldn’t say who they were. Nor would I have been able to identify the boy who put the frighteners on me. ‘I can fix it’, he boasted, ‘ so you’ll never have pleasure pissing again. Nobody’ll ever find the mark. I wonder what he ended up doing.’

‘He’s probably now working On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Was there any limit beyond which they daren’t go?’

‘ They had one rule. Never hit a boy with glasses—.’

‘I’m glad to hear that,’ I thought.

‘—- hit him with a cricket bat,’ finished John. ‘But not so hard there’d be any evidence. So they applied the Tempura Technique to their bespectacled victims.’

‘How’s that?’

‘They left them lightly battered.’

‘Then there was the bully who could never finished the fights he picked. He had attention-deficit disorder. And then there was the Billy Bunter boy who I easily distracted.’

‘How did you manage that?’

‘It was a piece of cake.’

‘When the bullies found out one of the new boys had a potentially fatal peanut allergy, they held him up against a wall and made him play Russian Roulette with a Marathon bar.”

‘ Bullies, by themselves are usually no problem. It’s when they’re in a pack they behave so viciously.’

‘Yes, we can never underestimate the power of stupid people in groups. I once saw four dirty big boys kicking and punching a smaller one. I said to a bigger boy watching ‘Aren’t you going to help?’

He said, ‘No, four should be enough.’

‘When I started to go for help, he warned me, ‘If you grass on us, we’ll rearrange your facial features in the Cubist style.’

‘That was their aesthetic?’

‘Without anaesthetic.’

‘’Your own mother won’t recognise you,’ this thug went on, ‘are you listening?’

‘Yes, I am. I still have one good ear.”’ He’d already landed me one on the other with the back of his hand.’

‘You didn’t hit back. Was this because you would have been seen as reducing yourself to their level.’

‘No. By bearing up against their assaults, by showing I could take them, I was actually hoping to bringing them up to mine.’

‘You shouldn’t have let them get away with this.’

‘I know but I was addicted to breathing. Bullying was endemic to this school. You never knew who was in the pack. It was a case of bully or be bullied.

‘It seems you took the biblical approach to all this. When someone hits you in the face, turn the other cheek.’

‘I did at the start.. That way the swelling is even. When it became unbearable and I realised there was no protection from anybody, I ended up starting my own gang. I gave as good as I got and learned to look after myself. If you can’t avoid bullies you have to get in quick and attack them without getting burnt yourself, or the dirty rotters will never leave you alone.’

‘Did this work for you?’

‘Ultimately, but not to start with. After I sneaked up on and attacked one lone habitual bully , he was all covered with blood. My blood.’

‘At least you weren’t anaemic. You made good of it after that?’

I did. One day this big bully came up to me and said, ‘There’s a little party after school, Johnny. You’re the guest of honour.’

I replied, ‘You can’t keep on doing this.’

He said, “What business is it to you?”

I said, ‘I don’t think it’s right.’

He said, ‘What will you do?’

I said, ‘Just wait and see.’

He said, ‘You and who else?’

I said, ‘The three of us: Me, myself and I. You’d better grow eyes in the back of your head.’

‘Who do you think you are?’

‘I am the last person in the world you want me to be.’

‘Did he fall for it?’

‘He fell soon afterwards. I sidled up alongside him in assembly and gave him a sharp kick in the shins. ‘That’s just to get your attention, ’I said.

‘I’ll teach you to kick me, ‘he cried.

‘You don’t need to teach me–I already know how!’

‘And how is that ? When your assailant’s on the ground?’

I never kick anyone when they’re down unless I’m absolutely sure they won’t get up.

‘So you learned how to return fire with fire.’

‘ They started it and I finished it. I vowed to toughen up and not be pushed around. I began by telling the rowdies where to go. They didn’t like that at all. One of them said to me, ‘Do you know who my father is ?’

I came back, ‘Do you?’

Once I gave the school bully a good going- over with a cricket bat. His arm was broken. Which is what gave me the courage to do it. The next time he approached me I thrust my cranium forcefully onto the bridge of his nose.’

‘Hey I’m bleeding,’ he cried as he held his hand to his face.

‘Good, that’s the sign of a successful head butt. When his gang threw rocks at me the following day, I returned their fire.’

‘You had a good pair considering they hadn’t dropped yet. What did the teachers do?’

They weren’t much help. I thought at least they’d give the bully a good talking-to. When I reported this to the short sighted teacher in charge of us, he said, ‘Why didn’t you come and tell me straight away instead of throwing rocks back.’

I said, ‘What good would that have done . You couldn’t hit the broad side of a barn if it was right in front of you.’

‘A bit of rough and tough never did me any harm,’ he declared, ‘apart from psychological maladjustment and blurred vision.’

So what do you propose?’

‘Just ignore them. They’ll hate that. They’ll just get bored. They’ve probably got issues going on. Just walk away from them .’

‘That’s easy for you to say. You don’t have them in your face 24 hours a day. Why should I suffer for their hang-ups.’

When I reported that one of them bit me on the arm and banged my head, all he could say was, ‘Boys will be boys. At least that one has good taste.’

‘Is that the best you can do? Are you going to treat the wounds?’

‘What do you want me to do? Kiss them better?’

‘What about this tear?’ I said, taking my hanky off the mark and holding my arm up to him.’

‘It’s only superficial. Don’t play the martyr. The pain is mostly all in your mind. And please stop bleating and bleeding all over my desk . I recommend you put this incident behind you. So what will it be?’

‘How about some iodine? And what about my head?’

‘It’s just a flesh wound.’

‘Wasn’t that what the Romans said about the Crown of Thorns?’

‘You’ll just have to put up with it.’

‘It damn well hurts!

‘What am I, your mother? You want a hug? Of course it hurts.’

‘What’s the trick, then?’

‘The trick, John Mellor, is not minding that it hurts.’

’‘The administration seemed to be making the rules as they went along. ‘What happened?’ the House Master asked me after their continuous attacks.

‘Three rabbit punches , two chokeholds, lots of heavy pushing, shouting and slapping and an incisor buried in my forehead.’

‘Toughen up. You’re like porcelain. Drop you and you break. They can’t have hurt you all that much.’

‘Nothing I won’t get over.’

‘There are no special cases here. These things will make a man out of you. Now grow up and stop being a cry baby. Don’t cry wolf every time somebody looks at you cross-eyed,’ was all he could come up with.

Everybody pretended the practice never happened. The morning after one blanket party, one of the teachers said to one victim, ‘Looks like you had quite a bash last night.’

‘Yes, I walked into a door.’

That’s not so clever.’

‘You should have seen the door, ’said the victim’s mate.

I reported the gang to that teacher when they threw paint in my face.’

‘That stuff can damage your vision.’

‘Not if one of the persons throwing it has a father on the school Board of Trustees. They throw things and then hide their hands. All the house master could say to them was, ‘Throwing paint is wrong in some people’s eyes.’

‘So they were let off easily.’

‘As long as they didn’t do it in front of others. The lesson we learned was this: it’s not what you do,it’s when and where you do it and who you do it to or with.’

‘So the school went along with this bullying,’ I concluded.

‘It worked it into the curriculum. If you knocked another kid out, you got extra credit. There was this one kid, he so wanted his friends not to fail, he used to say to them, ‘Hit me, hit me. What’s the matter with you? Don’t you want to get good grades? He was the youngest kid in the history of the school to graduate in traction.’

‘So the bullies exempted no kid from this treatment ?’

‘They were vicious but fair.’

‘Tell me, what did that kid come away with from this?’

‘Save for a little blood in the urine, he was no worse for wear.’

‘Do you think bullying is built into the ethos of the private school system?’

‘I believe so. It’s practice of allowing kids to be pinned down is believed to prepare them for the real world. The attitude is things aren’t real unless they hurt.’

‘And it affects everyone in the school community.’

‘Yes. I remember one victim who went to the head teacher and complained, ‘Mervyn Cooper’s been punching me every day since the start of term. I’m not going to teach him any more.’

‘Schools must take steps to prevent and stop bullying. This involves a commitment to creating a safe environment where children can thrive, socially and academically without being afraid.’

John’s vacation excursions took him where the oppressed were groaning. Locations such as Cairo and Tehran where he witnessed the local enforcers working over the wretched of the earth, knocking their blocks off, grinding their faces into the dirt, slamming their heads into the wall. Just because their I. D.’s were not forthcoming or their ideas unacceptable. Just because they didn’t like the look of them. Just to watch them suffer.

A case that couldn’t be solved with their size 12 steel caps didn’t warrant consideration.

Consequently he had strong sympathies for the underdog in society. Strong respect for them withal when they stand their ground.

“That’s why Sillitoe’s characters appeal to me’, he said, ‘While the other ‘angry’ writers depicted those short changed in life trying to emulate the upper classes, his revelled in defying the high and mighty. The upper crust-a load of crumbs held together by dough.’

John had done a stint at art college which explained his drive to re-define the character of rock. We both felt driven by a fierce desire to help a classless civil society, with productive property owned collectively like in the G. D. R. but without its repressive state apparatus, with a tight knit community spirit like those in Northern Ireland but without its divisive religious ideologies.

“No small order”, he said, ‘but the only direction to take. As individuals we can all have a positive effect on the future of the world.’

‘We’ve got to accentuate the affirmative and eliminate the negative. Not mess with Mister–In-Between.’’

‘Together we’re unstoppable. What happens is what we make it. It all depends on the decisions we consciously make. What the future holds is unwritten.’

‘Yesterday’s history. Tomorrow’s a mystery.’

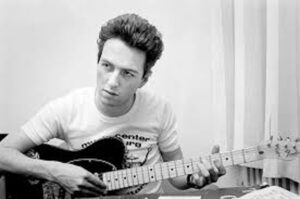

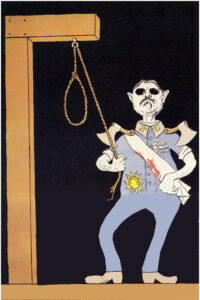

Class and caste were big issues with John, who became painfully aware how young people searching for meaning could be led up the garden path by dark political forces. He talked about this when I asked about the words adorned one one of his old battered guitars, propping up a cardboard covered window, it’s sash cord gone: ‘This machine kills fascists.’

‘What’s the deal?’ I asked. ‘Would you attack them with the neck? Is that a fret?’ ‘That’s what Woody inscribed on his guitars,’ he explained.

‘Could you expect the judge to respect that authority? Could he take into consideration the motives for your going about the attack. That you’re a first offender?’

‘No, first a Gibson! Then a Fender!’

‘I see you’ve got several guitars. Do you need so many?’

“I sold one recently to a double amputee. A man with no arms . I asked him how it was going to work.

He replied: ‘I’m going to play it by ear’.”

What about this one on the window?’

‘I’m going to sell it.’

‘Would the purchaser have to use it for killing fascists? ‘Would you apply special conditions for it?’

‘They could use it for whatever purpose they choose. They could restore it . They could use it as a prop. They could use it as a drum. There’s no strings attached.’

‘I recall now what Pablo Casals said in reference to the Spanish fascists. ‘My cello,’ he said, ‘is my weapon. I decide where I play, what I play, and before whom I play.’

‘We make a statement by our presence and by our absence.’

‘So you’d agree culture can have a vital role in shaping people’s consciousness and actions?’ I said .

‘Not half’, he replied. ” Artists can tell the world something it needs to hear.’ ‘But can art change a man or woman?’

‘No. That is what life does. Art is no substitute for life. However art can give meaning, can render meaningful areas of experience, and most certainly also enhances. Art can make people angry, can inform or inspire them. It can help steel the backbone of those in the midst of a struggle and help put wind in the sails of social justice movements. From the juke box to the ballot box. It can make them feel they’re not on their tod. It can make them feel better when they’re low.’

‘Can you think of any examples from the part of musicians?’

‘Woody’s is a case in point. He did his bit for the war effort against the Axis , serving as a mess man and dishwasher with the U. S. Merchant Marine . He frequently sang for the crew and troops to buoy their spirits on those perilous transatlantic voyages. When loading the ships, officers would be shouting at each other, ‘My niggers can load faster than yours!’ Woody bearded officials when he refused to sing to whites only.’

‘He saw fascism as the biggest danger to humanity, right?’

‘Woody saw it as the mortal enemy of everything he believed in – people, unions, democracy, human rights, justice, peace, world brotherhood, you name it.’

‘ So since the function of fascism is the exact antithesis, Woody was what you might call a natural-born anti-fascist. All right, now after the war he and his comrades sought to bring more zap and a heightened consciousness to the labour movement’, I said.

‘As part of the Almanac Singers he performed at union meetings and picket lines with the hope of galvanizing union action through their songs. Their rallying songs, focused on organization and mobilization, consistently employing the word “We” to stress the unity of all workers.’

‘Like ‘Solidarity Forever’. The repetitive nature of the lines and the constant refrain make songs like this conducive to group singing.’

‘A good example. These organizing songs were designed for the picket line and mass demonstrations. They boost morale and evoke the potential beauty of a world remade. I share his belief that given the right songs, downtrodden people everywhere can rise up singing.’

‘ Woody’s political pieces have undoubtedly become part of the American lexicon. Most of what people view as the populist American dream has its roots in the folksy socialism he practised . Many of the songs that leapt and tumbled off the strings of his music box are concerned with the conditions faced by working class people.’

‘His life work consisted of making up and singing songs to strengthen the arm of the poor, and especially their unions, in their struggle to shake off the shackles of the rich.

And of course there’s one that conveys this more than any other.’

‘No song wraps up his vision quite like “This Land Is Your Land.” At the same time exposing the problems of capitalist society, reclaiming the world for the common worker, it imagines all citizens having equal access to, as well as sharing, nature’s beautiful bounty.. The Dust Bowl balladeer cocked a contemptuous snook at class inequality’, said John, strumming the fourth and sixth verses:

As I went walking, I saw a sign there,

And on the sign there, It said “no trespassing.” But on the other side, it didn’t say nothing!

That side was made for you and me.

In the squares of the city, In the shadow of a steeple;

By the relief office, I’d seen my people.

As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking,

Is this land made for you and me?

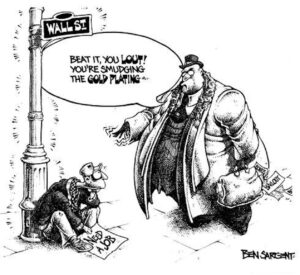

‘Our home-grown fascists answer no’, said John, looking up. ‘That it’s reserved for people like them- white anglo- saxon protestants- and they’ll clobber anyone who doesn’t fit in with them.’

The Teddy Boy’s Picnic.

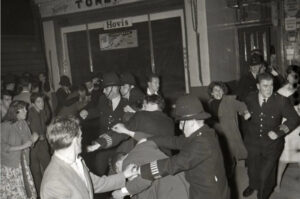

‘This is the spot where they sparked some of the worst racial violence Britain has ever witnessed,’ John pointed out to me one day as we were entering Latimer Road tube station.

A white mob rampaged through these streets armed with weapons, including sticks and butcher’s knives, shouting “Down with the n*****s” and “Go home you black bastards”. They greeted Caribbeans and police with a shower of flying bricks and bottles, broken glass and other debris.

‘What was it that lit the touchpaper? I asked John.

‘One evening in’58 a gang of warped white youths witnessed bickering outside between Swedish Maj Britt Morrison and her West Indian husband Raymond .

Hurling insults, the youths were taken unawares when Maj Britt turned on them. The following night, seeing her alone the Teds-mainly young white working-class ‘Teddy Boys’

–don’t let the name fool you-laid into her. They pelted her with stones and bottles, and hit her with an iron bar until she was carried away by police.’

‘It sounds like a very one sided affair. How did the black community respond?’

‘They gave as good as they got. After three days of constant rioting the tide finally turned. A group of mostly Jamaicans retaliated by throwing home-made Molotov cocktails on to the baying mob. As the white crowd backed away, a few of the West Indians gave chase waving machetes and meat cleavers. In homes which the mobs could break into women kept pots, kettles of hot water boiling, added caustic soda and if anyone tried to break down the door they could lash out at them.’’

‘Surely there was something in the wind this might come about.’

‘This was a disaster just waiting to happen.

Since the early 1950s hard up white families, fearing white replacement, competing with poor Caribbeans for housing, simmered with hostility towards the growing numbers of black families in the area.

Right-wing groups exploited these fears and prejudices.

Fascist groups such as the Union for British Freedom set up branches in the district. Sir Oswald Mosely, founder of the pre-war British Union of Fascists, held street-corner meetings in west London and further afield. Leaflets and wall slogans urged ‘Keep Britain white! The National Front are just the latest front for these miserable malcontents.’

To rally support, it’s pitch to disaffected youth was that white Britain had to be defended forcefully against less civilized peoples chiselling in.

The self appointed defenders were a hotchpotch of classical fascists, white supremacists and neo-Nazis .

They deemed it the patriotic duty of their select group to take actions against blacks and the Irish no matter the consequences.

In the film “This is England” the National Front leader would quote seductively from the oration of Henry V before the Battle of Agincourt, “We happy few, we band of brothers”. John’s brother had run with the thugs of the National Front before he killed himself.

‘David became withdrawn, solitary, and far from happy before he overdosed. This made me feel very ill at ease. I warned him off those Nazi pieces of work”, he told me.

‘He who rides a tiger is afraid to dismount.’

“What with their orphic claptrap and the occult that went with it, it’s not wonder he was screwed up. I had to identify his body. I’ll make a point of identifying theirs, in spades” he vowed, ‘and I’ll stand on their graves and tramp the dirt down.’

Desert Island Discs.

John rifled through his record cabinet and boxes. He had a serious case of spins and needles. After pulling out various possibilities, John spun me some of his favourite selections running the whole gamut of popular music- some of the most exciting music ever committed to vinyl. To guide his choice I suggested that we play desert island discs, based on the popular BBC program. ‘It was first broadcast here in Maida Vale, in a bomb damaged studio, back in the Bakelite era’, I informed him. I reminded him of the rules: ‘You have to choose the eight records you’d take with you to a mythical desert island. You have to imagine spending the rest of your life there as a castaway, marooned indefinitely.’

‘If that’s the case, I’d take my eight records for long distance swimming. I was awarded these at school for escaping my tormentors.’

Discussing his hit parade was a device for him to run over his life. ‘You also have to choose your favourite book apart from the Bible or other religious work and Shakespeare – these already await you- and a luxury which must be inanimate and have no practical use. ‘These choices will reveal your emotion and character, tell me about your life and the music flowing through it — music that touches a chord, recaptures a moment, offers solace, comfort, meaning and happiness.’

‘I’ve already mentioned ‘This Land’, said John, ‘which has to occupy my top slot. I’d have to have something by The Stones in my grab-bag” he said.

‘Where did you first come across their sound, squire?’

‘I first heard them in the heat of the African night. I was fiddling with the dial on my father’s short-wave radio in a desperate bid to find the sound of home. Through the crackle of reception I picked up the UK chart run down and was amazed that even in Blantyre, Malawi, in the middle of Africa I was receiving radio from Britain. I became interested in them and The Beatles and, importantly, their affection for American rhythm and blues, as well as the local Malawian music. It’s the Stones who got me started in my unsettled work habits. I was a lousy student who got lousy reports. The Stones may well have sung “Not Fade Away” but my interest in school did.

‘In academic learning, ’I said.

‘You bet your sweet life! I tuned out of those tiresome discourses and totally into music- rhythm and blues. The only way people should get their kicks. It was the only thing that settled me down . I set about exploring it’s development through my strings”.

It sprung to my mind where he and his brand of sound were coming from. From swing was born jump blues, which in turn helped create rhythm and blues.

John loaded his turntable with some hits making it onto the local West Indian sound systems. Boy did he let it blast. Like myself, he was gingered up by the musical accomplishments coming out of Jamaica and gaining a foothold in West London. We shared the wonder and the outrage in the voices of Jimmy Cliff and declamatory visionary Bob Marley whose gospel had been shaped in the sprawling squatter hovels and shacks of Kingston he was jungled up in after being left homeless. “What I would love to do” he said “is to bring rock and reggae together and bring it to a higher level. To get everyone moving together. There’s nothing more I’d love to do than play with these guys”. He believed strongly in the redemptive power of music and that it would be through his mastery of this art that he would reach out to those who he knew from experience felt badly done by, isolated or driven to distraction.

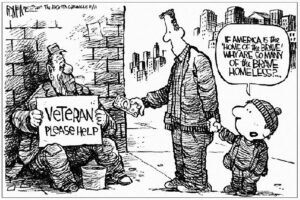

All the lonely people. He knew where they all came from. Sitting on their hands, looking for something in the cause of nothing. His brother’s self destruction weighed heavily on him and was a lesson in what could happen when loneliness and a sense of hopelessness were allowed to fester. This could happen when those feeling like this read the headlines and felt like saying, ‘Stop the world, I want to get off!’

As a consequence he wanted to write songs that would get those down in the dumps, who woke up on the wrong side of the bed, who thought the whole world was against them, that life was passing them by, to turn theirs around, come out of their shells and enjoy it with everything to live for. He wanted them to take full advantage of life’s opportunities whenever and wherever they present themselves and to live it to their full potential. He knew they should all belong, proud members of a society. Part of it, not apart from it.

33 Revolutions Per Minute.

A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once,

but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over. — Joe Hill.

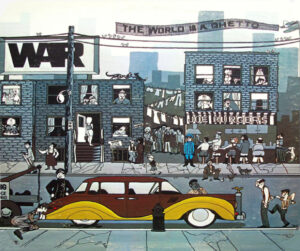

On a visit to my home, it was my turn to treat John him to some of my black discs .

‘Settle back for a guided journey across 110th street through the derelict urban soundscape. I’m going to spin you some of the most genuinely brilliant, challenging records of our time’, I announced. ‘Longish orchestrated soul-epics, liner notes about dysfunctional life in the American ghetto. Of a piece, they They drill down into the wild social and political distresses that go on around us here in Britain to a lesser extent, crippling the progress of the whole world.’

‘Not what you might call lullabies’, John said.

‘They don’t soothe the savage breast but like the town crier wake us up with a message’, I said, ‘ taking it to the streets, without compromising their art. They make the bitter pill go down smoothly. Thanks to a determined group of composers to whom something happened in the 60’s , incisive subject matter, audacious topical comment and pertinent political statements are back on the musical agenda’, I said.

It’s about time,’ said John. They’re long overdue.’

‘They’re not mellers, Mr Mellor,’ I said, using the entertainment industry word for melodrama. ‘’The themes expressed in this music are channelling the anxieties, aspirations and frustrations of the world in an unprecedented way. I’ll provide the liner notes, cataloguing the multitude of deep-rooted social ills they deal with. Inspired by the civil rights and Vietnam war protests, they take us into an inner city racked by disturbing poverty, unemployment, civil unrest, criminal violence,

police brutality, drug abuse, amid the urban dry rot and environmental woes that surround people .

‘People grow up fast there.’

‘If they manage to do so. There where the first lesson children coming up hard have to learn is not their ABCs, but how to duck under the nearest parked car at the first sound of a loud noise—gunfire. They help us understand how the violence is a result of “self-hate”. A hate created by the suffocating images of inadequacy and inferiority America imposed on its own black people. Can you take such heartrending songs ?’

‘One good thing about music, when it hits you fell no pain

So hit me with music, hit me with music.’

So I hit him hard. He was used to it from his childhood. To kick things off I played the Whitfield and Strong’s deservedly titled ‘Masterpiece’, sung by The Temptations.

‘This gives us a birds-eye view of the situation’, I said. ’It paints a sombre but inescapable picture of the desperate dog-eat-dog existence endured by many. About the frustration of mothers, queasy about the hot water their children get into . Such as that of the naïve poky drawling country boy, ‘Living For The City’, I said, slipping on Stevie’s damning indictment of exploitation and injustice. ‘ Working their cotton picking fingers to the bone for bugger all, his parents live for the possibility that he will make a new beginning in the city . No sooner there, nowhere to live, poisoned by the toxic air of the cold cruel city’, this ‘nigger’ is hustled into running drugs, arrested and sentenced to 10 years in jail.

Not really a living at all, even for Marvin, who knows this territory -‘The Inner City Blues’- only too well. Watching the wealth he’s created taken by bosses , bills piling up, taxes going unpayable, his savings whittled away by galloping inflation,

demands for his military service abroad.’ Throwing up both my hands a la Marvin, I cried, ‘Oh, make me wanna holler.’ He sings about the extravagance of investing in space exploration. Over the years, it seems that governments has been more intent on discovering life on other planets, than on discovering ways to save lives here on Earth.

Leaders have much experience in telling us how far in debt we are. Yet there seem to be endless billions funneled into the space program. We’ve gone right up the spout when we sends dozens of people to outer space, but neglect to feed the millions who are famished and poor. You may leave here for four days in space But when you return it’s the same old place.’‘ Who could have believed that Mr. Smooth, the Black Sinatra, the second coming of Nat King Cole, an apolitical, musical Don Juan would have come out with such an anti-war, quasi-religious, save-the-babies, save-the-earth melodious screed’, said John. ‘Look at the cover: the man is dripping wet, standing in the sleet. He must have put a damper on some hedonistic hopes! ‘Note, John, there’s no question mark in the title. It’s not a question but a promise that listeners would be clued-up by what they hear, Marvin’s feelings on what has happened to the American dream.’

This drive for urban affluence can be such a misdirected goal’, said John. ‘We can lose vital values and humanity on the way. As Stevie Wonder warns in ‘Living for the City’, ‘If we don’t change, the world will soon be over’.

‘He does end on a positive note,’ I added, ‘reminding us of the possibilities of life. Comparing our social life with something better. ‘I hope that it motivates you to make a better tomorrow,’ he sings.

‘Likewise with Marvin. His observations of the times are often bleak. He sees people having to form picket lines over achieving every social need.

Still and all his overall message still and all offers the promise of redemption. The overriding message of ‘What’s Going On’ is ultimately one of hope: we can save ourselves only if we can learn to co-exist with our neighbours. We have to re-create caring, supportive, sacrificing communities like the one the young man came from, so that people don’t become unmoored or fall by the wayside.

‘We have to build a social tower of strength. This is the ‘What’ what the Left Rev. Mc D., the former clean-cut Gene McDaniels hints at in the tradition of the black Baptist preacher . Initially cast, like Marvin, as a suave good looking performer of upbeat pop songs aimed at white teenagers, he came up with the protest song ‘Compared To What’. This howl of indignation with its uncompromising lyrics challenged the very sanity of the world. Gene contrasts “the social myth of equality and the economic reality of poverty in the stratified American society. He writes about a president sending the young to die for reasons as murky as the jungles they confront. ’

‘ Back to ‘What’s Going On’, compared to most releases, it’s a killer thriller’, said John. ‘The sounds tell this all too familiar story. Every city has people going to the outer limits to make ends meet, determined on by hook or crook beating the odds, even if they are ultimately stacked against them. And unfortunately, countless families suffer from the feeling of hopelessness from having to visit a relative behind bars, treated too often like beasts, not men.

‘And when they revolt to seek better living conditions and political rights, they can be set upon savagely. John and Yoko remind us about the Attica penitentiary uprising. They issued a scathing condemnation of the American judicial and penal system with such lyrics as “Free the prisoners, jail the judges,” “They all live in suffocation,” and “Rockefeller pulled the trigger, that is what the people feel.” The final verse calls on its audience to ‘Come together, join the movement. Take a stand for human rights . Fear and hatred clouds our judgment. Free us all from endless night.” They performed the song at a benefit concert for the families of those killed in the rebellion.

‘These songs are a reflection of everyday life,’ I said, feeling Stevie’s song coming on.

‘Listen to how the anger and tension build and boil over in Little Stevie’s growling voice. It matches the growing frustrations of the subjects in the song beat for beat. The hand clapping and background female vocals remind us of the warmth and community of the Southern church, giving way in stark contrast to the’ tic toc’ marking industrial time and the street sounds of car and bus engines and the blaring sirens of police and ambulance.

‘ It echoes Elvis’ In the Ghetto, doesn’t it?

A young boy who is born there, grows up, steals, gets into scrapes , and eventually is shot and killed as another child is born. There’s the strong implication that his fate will be the same. The vicious circle. Just another one of those things’

‘Little wonder that they fly off the handle when the moment presents itself. It doesn’t take much to trigger things off.’

‘There were initial fears that ‘In The Ghetto’ would sully Presley’s reputation for being ‘politically unbiased’. While hesitant, he loved the song and recorded it anyway. He injected drama, pain, poignancy and hope in a way that nobody else ever could. He wanted the number to reflect a musical version of what Martin Luther King’s “Dream” speech had become’.

‘How can you be unbiased about something obscene as mass poverty’, I asked.

‘At least some of the reforms passed by Congress to combat straitened circumstances and create programs, designed to reach out and improve the lives of poor children caught in cramped American rookeries, can be traced to the heart to heart, prayer-like manner Elvis sang this song.

Elvis’ voice and determination brought a problem into a context that anyone could understand. It woke people up and forced many to look beyond long held prejudices’.

‘But not all’, I said, seguing into The Tempt’s “Cloud Nine,” addressing drug use . ‘This stirred up a hornet’s nest. It’s one thing to garner sympathy for poor innocent children, another for poor, not so innocent adults. The busted flat, unemployed, and despondent main character, proclaims that he has to ease his troubled mind, by “riding high on ‘cloud nine'”, a million miles from reality, where ‘ you ain’t got no responsibility’. That’s why he gets out of the rat race.’

‘The trouble with being in the rat race is that even if you win, you’re still a rat.’

‘The song stunned some who are in it. They interpreted it as sympathetic to drug use, although Whitfield, Strong, and The Temptations deny that it’s about that’.

‘They would wouldn’t they, said John’. Otherwise they’d be crucified’. They have their clean –cut image and their careers to preserve.’

‘They don’t excuse such practices, merely draw attention to the social context that can give rise to them, ’I said.

‘They must have known that people were going to assume right off the bat the song was about drugs, especially singing about partying at the ‘psychedelic shack’, where people go to ‘do their thing’. Nudge nudge, wink wink,’ he said laying his finger alongside his nose; giving it a slight tap. ‘ But just hinting at it is too outrageous for our moral guardians. They don’t welcome anyone telling it like it is. They want us to hide our heads in the sand and make believe it’s not there, clap our hands for Tinkerbell, or blame users totally for their own problem’. Let’s face it, people turn to drugs to escape whatever pain they find difficult. It’s an occupational hazard in the music world.. It’s just that much harder if you’re without a penny to your name. We have to improve social conditions and educational awareness, and that’s what the same hardliners will always stand pat on. They will pin the blame on the victim and those parents who shirk their personal responsibilities. The character in the song had nothing going for him in every respect. His father was abusive, treating his family like dirt’, said John.

‘When it comes to paternal abandonment, my next is about the daddy of them all’, I said. ‘I’ll tell you the storyline so you’ll come up with the title. This funky , social realist bleak tale is about a family reunion in which brothers ask increasingly-pointed questions of their mother. They want to know the truth about their now-deceased cad of a father who was never around, who they only know through word on the street, have ‘never heard nothing but bad things about him.’ All they know is that he’s a liquored up lying womanizing forked tongue who never worked a day in his life—’

‘A familiar story’, John said, ‘To him, nine to five was odds on a horse.’

‘This father was hiding behind God, and, depressingly, choosing another wife and ‘outside children’ over them. Witness:

:Hey, talk about Papa doing some store front preaching.

Talked about saving souls and all the time leaching.

Dealing in debt and stealing in the name of the Lord.’

’Of course. “Papa Was a Rolling Stone”‘, exclaimed John. ‘What a bleak chilling tale. Such striking language. What gives the song its resonance is their mother’s repeated completely defeated response:

Mama just hung her head and said,

“Papa was a rolling stone, my son.

Wherever he laid his hat was his home.

(And when he died) All he left us was alone.”

‘By the sound of it his old man was a workaholic. Every time he thought about work, he got drunk.’

‘To the son his dad was like a black James Bond: it would have been great to see him, but he was unlikely to make an appearance.’

‘And now for extra credits, what’s the title of this song?’ I tested before putting on my next platter that mattered . ‘It deals with the plight of runaway children. Just like those who end up on our association’s doorstep. . This is the terrifying tale of a young shaver who runs away from home. He’s been hung out to dry for wagging it. The boy wanders the dark streets alone, eventually realizing he cannot survive on his own. He can’t find his way home. He ends up lost, frightened by strangers, unfamiliar landmarks, and his own thoughts. The Temptations tell the boy during the chorus, “you better go back home/where you belong”.

‘’Runaway Child, Running Wild’, said John. ‘This would give any kid listening to this second thoughts about doing so.’

Another obvious choice of mine was The Tempts single “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today),” the ambitious complex sonic whirlwind that piled on topical lyrics and rhymes, describing a world hitherto rarely discussed in such blatantly political terms.

‘It tries to wrap up everything questionable tearing the world apart in in one neat package, I said. ‘The Vietnam War, segregation, white flight, drug abuse, crooked politicians, homelessness and more, too hard to leave aside.’

‘Great balls of fire! What an opening salvo it fires’, said John. ‘A clean electric guitar strumming a hard funk riff in time, centred on pretty much one chord’.

‘It grabs you by the collar with the very first two sentences, I added:

“People moving out, people moving in,

Why? Because of the colour of their skin,

Run, run, run, but you sure can’t hide…”

‘We’ve barely started, yet the picture already painted leaves us in no doubt that we’re dealing in harsh realities here. It reflects the jam most black Americans are in, disillusioned by the slowness of change when it comes to their personal freedoms, whilst inhabiting a world that’s been changing at breakneck pace. As they try to make sense of the situation they find themselves in, things only become ever more bewildering, This title perfectly captures the mood of the moment.’

“Round and around and around we go”, the Temptations sang rapid-fire, “where the world’s headed nobody knows.” My guest and I joined the group with an intense wham shouting: ‘ Hey oogabooga, can’t you hear me talking to you, just a ball of confusion. That’s what the world is today… hey, hey! and then just their bass singer. punctuating the end of each section of the lists of woes with the adage of complacency “And the band played on’

‘Evolution, revolution, gun control, sound of soul

Shooting rockets to the moon

Kids growing up too soon

Politicians say more taxes, will solve everything

And the band played on.’

‘Ball of Confusion is indeed at sixes and sevens,’ said John. ‘ Nearly every instrument – electric organ, wah guitar, drums and vocals – is threatening to strangle each other in the mix. It’s not in so many words a fun song, but it’s a lot of fun to get your ears around with its topical, clever references, loping, persistent groove and irresistible hook.’

‘ Talking about politicians with simple solutions Stevie Wonder’s “You Haven’t Done Nothing, springs to mind “, I said, putting on The Masterblaster. ‘Just listen to him take to task those politicians who will say anything to get elected and stay in office: “But we are sick and tired of hearing your song/telling us how you are going to change right from wrong.

’It’s aimed squarely at Nixon’, I said, switching discs. ‘Hark to how he handles this theme in “Big Brother.”

‘This really hits the right buttons, ’said John. He takes ideas from ‘ 1984’ and adapts them to today’s America. He tackles the hollowness inherent in politician’s claims here.

They come into the ‘hood promising the poor, the unaccommodated and disenfranchised the world and cut them dead once the elections are over. They don’t act fair and square.’

‘Honesty is the key to them being elected, If they can fake this, they’re in. This includes those who lose having promised the constituents extravagances they will deliver.’

‘My local Conservative Party member was one of those. He failed in his bid to re-enter Parliament. He recently knocked on my door. Guess who was delivering my pizza?’

‘Most politicians can be considered honest in one respect only. When they are bought, they stay bought.’