Driving through leafy Potts Point some time after getting the push, I chanced to pass an earlier refugee from the Education Department walking along the street. Russel Ward was on one of his trips from Armidale.

‘Well I’ll be damned, it’s Allan. I thought the earth had swallowed you up. How are you?’ he asked.

‘All the better for seeing you, Russel. It’s a small world isn’t it.’

‘I see you are now Deputy Vice-Chancellor at U.N.E.’

‘Yes, the culmination of my long descent into respectability.’

‘What does that entail?’

‘DVCs are normally empowered to substitute for the vice-chancellor in both ceremonial and executive functions.’

‘When do you fill in in this role?’

‘When he or she is absent from the university.’

‘So you’re a substitute for another guy or girl.’

‘Why not. I look pretty tall though my heels aren’t high.’

‘You looked the part when we first met. However as I learned in my dissertation a uni’s not simple to run. You have to understand generational change.’

‘The simple things you see are all complicated.’

‘I have to think like the young so I’m not back-dated.’

‘I see your shoes are made of leather.’

‘I think we look pretty good together. You must come home with me for a spot of lunch. Come on-a my house’.

‘If you’re gonna give me figs and dates and grapes and cakes, you’ve got what I takes.’

‘I’ve got coffee to offer too, nothing ersatz, no fakes.’

‘No substitutes for this substitute, eh!’

As we passed Challis Avenue Russel said, ‘Peter Finch took a room in a boarding house down there while he started picking up acting work.’

We detoured down the avenue to have a look.

‘So things weren’t so easy for him at the start.’

‘That’s what attracted him to making his choice of cinematic debut, Dad and Dave Come to Town. The story of struggling farmers, the Rudds from Snake Gully. These country cousins inherit a struggling women’s clothing shop in the city.’

‘A film that still reels them when shown in cinemas. A story I feel would be right up your mallee, Russel.’

‘Peter was the classic struggling actor. Don’t forget this was the 1930s. He shared cheap digs around here with other of my friends from the New Theatre. Often down-and-out, he slept in doorways and in the Domain.’

We drove along the notorious Darlinghurst Road neon strewn strip, through the centre of what was then Sydney’s red light district.

This may well be my last time here, old son,’ said Russel. ‘I’m taking all this colour in. I may never pass this way again.’

I parked on the corner with Roslyn Street while Russel filled me in on the area’s past and I pointed out the current state of play.

‘Life has changed a lot here since the war,’ said Russel.

‘In what ways?’

‘Life here was fairly quiet, at least in my circle of friends who worked elsewhere. They relaxed here evenings in their own company, at a café, or in one of their flats, chatting around the gas fire. They had a shilling in the stove slot gas ring and a hot bath down the corridor.’

‘So that was living it up?’

‘It was all about freedom to live how one wanted. ‘It was an oasis that defied the tyranny of suburban mores and morals. For single women there was freedom in living in an inexpensive flat of one’s own away from the prying eyes of family and nosy neighbours. It became a place where people were different.’

‘So this Australian Montmartre was a small island of tolerance.’

‘A place where unmarried couples, homosexuals, artists, actors, bohemians, dancers, musicians could find like-minded people. When other parts of the country would not accept Jewish refugees from Hitler, or those escaping from the pandemonium of post war Europe, the Cross did. For drag artists and the transgender it was a place of acceptance. Tolerance and diversity reigned. You weren’t morally judged for your sexuality, foreign accents or preoccupations, as you were in the rest of Australia. Ladies of easy virtue, gangsters, booksellers, doctors sailors, drug dealers, crazies, judges, artists and eccentrics lived side by side. There was a complexity of human interactions, stunning juxtapositions of beauty and ugliness, underscored by an arrogant sense that it was markedly different from the rest of the country.

‘What was the character of the Cross that set it apart?’

‘It used to be famous for it’s colour, diversity and wit. From the 1920s onwards it was at the vanguard of apartment living, urban architecture, interior design, nightlife, fashion, food, music and theatre. While the rest of Australia retired to bed, Kings Cross came alive. The streets pulsated with people, goggle-eyed sightseers, fashionably dressed men and women, musicians with instruments rushing from gig to gig, ladies of the night with their gravity-defying hairdos, strippers hurrying from club to club, late night shops with signs announcing their wares still open, gays at their favourite watering holes and naval ratings on shore leave putting it away.’

‘Lots of Yanks around.’

‘While the rest of the country still looked to Britain for inspiration, the Cross duplicated American energy, popular culture, even its fast food. Sailors and servicemen disembarking at the wharves would immediately hurry up the hill to visit it.’

‘What did they see when they came?’

‘They flocked to see its dazzling visual cacophony of bright lights and visit its sophisticated nightclubs, continental restaurants, swish hotels. And for those who were daring: gay bars, strip joints and the colourful “female impersonators”. The Cross became the subject of paintings, films and pulp fiction, and tabloid editors loved it. The name was a shorthand for sin and sex, even if the definition of the place extended as far as Darlinghurst and Surry Hills.’

Well you’ve still got all those kinds of people coming here as well as the hordes of yobbos from the outer suburbs. Bohemians and artists, creatives and writers, all those hopefuls, with their dreams and aspirations come here. You’ll witness passing by us the widest cross-section of this area today. It’s filled with all manner of characters and chancers with various intents.’

‘Most look like ordinary people going about and minding their business.’

‘Most of them are as far removed from crime and corruption as anyone else.’

‘Look at all the tourists. What do they come to see?’

‘In this theme park of human misery they can watch the drunks, the bag ladies, illegal gamblers, the drug-addicted, pimps, the prostituted street kids. This spot gives you a ringside seat into these dodgy aspects, street brawling and encounters of the turd kind. Shady types often, well outside of anything respectable, up to no good. Street fights and mysterious screaming can break out at any time, though mainly in the early hours.’

As we sat there our eyes were caught by the sight of this person wearing a floppy straw hat, sky-high platforms and hot-pants, hovering around on the opposite corner.

‘What do you reckon, Allan, is that a man or a woman?’

‘Around here it’s hard to tell the difference. This person looks too feminine. She must be a bloke.’

‘Allan, that very spot where he or she stands was where Jessie Street pleaded for peoples’ pennies. But it wasn’t to support her habit, waste on grog or supplement her dole that she worked that corner. It was to support her causes.’

‘Who was Jessie?’

‘ Jessie was a high profile feminist and a voice for international peace back in the 1930s. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union she mobilized to raise money for that front.

All those small global contributions added up to a whole lot, helping bring final victory.’

She went on to advise the Australian delegation to the United Nations led by Bert Evatt.’

’Also advised, as you pointed out to me once, by none other than our future foreign minister Hasluck.’

‘She must have known Beatrice Taylor. Beatrice, the proud ninth child of a miner, joined a tour of the Soviet Union organised by Friends of the Soviet Union in 1932.’

‘Jessie knew Beatrice well. They shared a vision of a world changed over, planned and built afresh. They were both sympathetic with a country that had been smashed utterly by years of constant war and suffering but whose people were again moving forward.’

‘She obviously admired the resilience of the Soviet people.’

‘Being very observant during her trip, Beatrice marvelled at how people continued to live, despite the tremendous strain and difficulties of Soviet life between the wars.’

‘What were the major attractions for her?”

‘She witnessed operations of the increasingly mechanized Soviet collective farms or kolkhozes.

She saw the ambitious industrialization program in action.’

‘Her observations of the past and present in the USSR claimed an insight into a country in transition, leading her to speculate on all the ways a country might deal with adversity. She liked the improved status of women and the quality of care in the hospitals. She admired the successes in eradicating illiteracy and raising people to a higher level .’

‘She must have come under the watchful eye of some of the apparatchiks.’

‘That came later on her return. The Department of Education also knew Beatrice very well. She was a public school teacher who had campaigned vigorously for equal pay for women. She had stood up against the dismissal of married female teachers.. When after her return she gave a public lecture on social and educational conditions in the Soviet Union, it asked her to justify her address. She refused, arguing defiantly that her civil rights as a private citizen would be impugned.’

‘She was in good company. That’s just what Paul Robeson argued upon returning from his visit soon after. Subsequently his passport was taken away and he called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). What punishment was meted out to Beatrice?’

‘She was suspended for misconduct and wilful disobedience.’

‘I’m not surprised, being all too familiar with the thinking of the Department. They would have wanted their staff to see only what they wanted them to see. They would have wanted their staff to hear only what they wanted them to hear. She would have been expected to reflect it’s ideologically impeccable achievements.’

‘In other words staff were expected to behave just as their counterparts would have been in the Soviet Union only with a different ideology. They had to know what they could and could not talk about.’

‘Was that the end of her career?’

‘Fortunately no. Beatrice fought hard for the civil rights of public servants. After a long campaign defended by Clive Evatt, Bert’s brother, she was re-instated.’

‘A win for all women,’ I said.

Both Jessie and Beatrice were very plucky, principled people. Russel, would you believe I gave out leaflets on that very same spot informing people about the U.S. not so secret war against Nicaragua. I raised funds for their literacy campaign.’

‘Sadly the wannabee empires haven’t progressed one iota in their thrust for dominance.’

‘In the thirties Germany launched it’s abortive imperialist war against the biggest country in the world. In the eighties the U.S. colossus launched yet another of it’s against one of the smallest countries in the world.’

All of a sudden a shrimpy guy ran across in front of us and down Roslyn street hotly pursued by one of the local scoungy looking gorillas.

‘Too much booze, a deal gone wrong.’ I speculated.

Ten minutes later the pursuer was hauled past us by a cop in the direction of the police station close behind us.

‘Cops in Kings Cross have one of the toughest beats in Australia. Many retire early, suffering from stress and depression.’

‘So why do people still come here? ’asked Russel as I switched on the motor.

‘Thousands converge here of a Friday and Saturday night. Because of the cost of drinks, many of them are pre-fuelled with alcohol. They come from the suburbs and are looking to have a good time. A familiar sight is that of a milling mass of thousands of drunken men and women with nothing to do. Fights break out and the stench of vomit, urine and ordure the next morning can be overwhelming. The nearby St Vincent’s Hospital has to deal with deaths, injuries and overdoses.’

‘All that damages the character that was one of charm and pleasure.’

‘It still has character though with a hint of menace. It’s actually tamer than reported. It’s safe to wander at pretty much any time of the day or even early at night. It has edge in the same way that your reformed hippie aunt still has an edge. It can be a little scary when the excitement and highs have died off. But it’s always interesting. It wears it’s proclivities on it’s sleeve, where nothing is hidden or denied.’

We passed an establishment that advertised ‘Live Dancing Girls!’

‘What would you expect’ said Russel, ‘stiffs on a piece of bungee cord?’

We turned right and went down William street.

As we proceeded we saw a few reminders of the area’s debauched past. Several working girls lining the street.

‘You know they’re in the only career in which the maximum income is paid to the newest apprentice.’

‘You can see even more in the hours before the cock crows’, I said, ‘ desperate drivers crawling slowly past the kerb, early risers seeking out the early openers.’

‘Of course, ’I said, ‘this is still clubland, where men and women meet each other without pecuniary exchange.’

‘This aspect brings back pleasant memories’, he said. ‘Of a priapic victory back in the thirties. As a student I was here with Herbert Piper for the inter-university debate. In the wee hours of the early morning, every other venue being blocked and barred, we were taken to a dance club along here on the way to Kings Cross. I felt extremely sophisticated as our Sydney host was scrutinized through a peephole in the massive door. It swung open to admit us only after he had pronounced some cabalistic password.’

‘Joe sent me?’ I suggested.

‘It had to have fourteen characters. Then I remembered. ‘Seven Brides for Seven Brothers.’

‘Did that work?’

‘Someone laughed out loud behind the door.’

‘This is a club for discerning clients.’

‘That’s all right with us. We’re not particular.’

We went in. It was a dark secluded place, a place where no one knew your face. You could only see silhouettes in that spot. And no one cared how late it got. Next day, comparing notes we felt even more adult and thanked our lucky stars for the two married ladies who had offered to help us get home. They gave us a lift.’

‘Did you go all the way?’ I asked.

‘ What else could we do. These sure things took us to their homes.’

‘In Rooty Hill, via Kissing Point? ‘I suggested.

‘Just down the road to Double Bay. When we got inside her apartment she asked me, ‘Won’t you join me in a little drink? What’s your pleasure?

‘Oh, what you’ve got there looks good.’

‘I know… but I thought you’d like a little drink first.’

‘Before I could say ‘Mrs. Robinson!’ she had me rolling around in her sheets.’

We turned left and entered Darlinghurst.

‘Darling it hurts.’ Russel punned. ‘This was a real slum area when I was first here. It was known for it’s early openers, pubs that throw open their doors at 6am or 7am. It was the red light district of Sydney. Burton Street here was in particular known for its door to door terrace brothels and street prostitutes. Here peculiar ladies did nod and the lodgers were rather odd. This is where Dave Rudd ended up one night.’

‘Dave Rudd from Snake Gully?’

‘This bumpkin was chatted up at Central Station by a lady of the night. Totally unaware of the lady’s profession, knowing nobody in the big, bad city, he was only too happy to take her up on her invite to stay the night at her place. She lit a fire, fixed him up a meal and provided for his every wish and comfort.

‘Some horizontal refreshment undoubtedly.’

‘In the morning she hustled up some breakfast for him.

As he prepared to take his leave, he said, ‘I’d better be off now, luv. Thank you so much for everything.’

‘It’s been a business doing pleasure with you,’ she replied, ‘ Now what about some money?’

‘Oh, dearie me, no. I couldn’t possibly accept any. You’ve been too good to me as it is.’

Heading down through Surry Hills, I pointed out another famous house of assignation. ‘That’s ‘A Touch Of Class’, I said, ‘ or as many pun, ‘A Touch Of Ass’-short for assignation of course.’

When we hit Elizabeth Street, Russel pointed out number 219.

‘Up there on the second floor was ‘Pakie’s Club’. It’s café, a ‘little bit of Paris’, was fashionable for its colourful modernist décor. It was designed with the assistance of Walter Burley Griffin and Roy de Maistre. It held monthly ‘international’ nights featuring aspects of the culture and cuisine of a particular country. ‘Pakie’s’ most famous dishes were salads and macaroni cheese.’

‘A very simple but healthy fare.’

‘The standard fare was not what you’d call exotic. ‘Pakies’ came to cater for struggling artists, writers and actors like Peter Finch .’

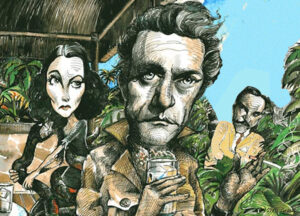

‘Well Peter would go on to more exotic tastes after Laurence Olivier and his wife, Vivien Leigh, discovered him.’

‘Yes, especially for Vivien Leigh.’

When we got to Rozelle, he asked what I was up to. I told him of my tangle with the Blind Giant: ‘My name’s been scratched from the list of available teachers. So much for my brilliant career in the Department. You know how it is, Russel.’

‘That takes the cake,’ he replied, ‘Alas, that’s public school teaching for you. Join the club. If you wanted a rough time, you came to the right place. As for ‘fair fighting, no favours’, forget it. The standard of public morality hasn’t improved over the years. Those moral carcasses, those faceless guardians of our freedom to think proper thoughts don’t seem to let up’, he sighed. ‘In the years since my run in with them, the personnel have changed for the who knows how many thousandth time, but the real location of power has not.’

‘Go over your disagreement with them and the lead up, Russel’.

‘In 1950 I applied for a lectureship in history at Wagga Teachers College. The interview was conducted in the Department of Education.

‘Not at the College itself?’ I asked.

‘No, the Department handled such matters. The grey, featureless, formal room I appeared at was reflected in the faces, demeanour and clothing of eight anonymous po faced males up in years facing each other across a long table, staring at nothing like a row of Easter Island statues. Not a smile, no flash of the whiteness of teeth. A ninth identikit geriatric occupied the chair at one end and an empty seat yawned for me at the other.

‘Were they alive?’ I asked.

‘When I sat down, none of them made any sign of recognizing me. They asked the usual inane questions customary on such occasions and my replies were equally fatuous.’

‘Did you get the job?’

‘Well I do declare, a few months later I received a departmental memo appointing me to Wagga subject to confirmation by the Public Service Board and ordering me to report at the beginning of the 1951 college year. I had no sooner arrived than I was ordered to return. Had someone mislaid the rubber stamp? Of course not. Everyone knew I was being blackballed for having been a member of the Communist Party. In Menzie’s Australia, troublesome persons, irrespective of party labels or none were the quarry of the thought police.

Eventually I got to speak to an education representative of the Board, a former teacher of book-keeping, who explained I was too highly qualified for the job, that it was best left to another whose masters degree, unlike mine, was unhandicapped with any kind of honours, and who had served many long years in primary schools.

‘How long has this been going on,’ I asked.

‘In 1816 William Broughton, an honest public servant, wrote from Van Diemen’s land to a colleague, Lachlan Macquarie in Sydney: –the roguery, which has been carried on at this ill-fated settlement is beyond all calculation—but how can it be expected otherwise when the very heads, with few exceptions, set the very worst examples.’

But unlike you, at least I was still allowed to work as a schoolteacher, as was one of the best known Communists Bill Gollan. Whenever I get plaints about Bill Gollan being a Communist,’ Harold Wyndham, the Director-General told me, ‘my answer is that he could bite a few other headmasters.’

I mentioned to Russel I had had a Communist headmaster at a primary school in London, a Mr. Luzio, and another, a nun, who was a Maoist.

‘Presumably they were too entrenched to ditch. Anyway, after this business’, Russel continued, ‘I was posted to Belmore Junior Technical High School. On entering, I heard familiar sound of a boy being caned : a swish followed by a crack six times. The head and all the male teachers wielded the rod freely every day. Canes and chalk were equally basic pedagogical instruments. the noise of thrashings echoed daily in the corridors.

At school I had taken for granted a modest amount of beating. Teaching at Geelong Grammar and Sydney Grammar I had caned, or caused to be caned, myself-maybe three or four times a year.

At Belmore, after all the severity of the War, cold-blooded, calculated violence had become repugnant. It didn’t mean I would turn the other cheek and allow any deliberately provocative hoodlums to walk over me. Occasionally when goaded beyond endurance, I would grasp one of the offenders by the scruff of the neck and seat of the trousers and give him the bum’s rush out of the door.

‘For an act like this today, you’d most likely be dismissed from the service, ’I said.

‘The trouble was these whelps treated you with open contempt if you were the only weakling who didn’t administer thrashings on demand.’

‘A shiver looking for a spine to run up?’

‘Blessedly I was appointed to North Sydney High School, a selective one, a haven of sweetness and light.’

‘So how do you think I should move my case forward? How and when can I find my haven?’

‘I hope you soon win the right for the right to appeal for which you have weaponised yourself . So hold your breath, be one hundred percent confident and go kick some goals. Can it be done?Unfortunately my crystal ball is broken. My forte is understanding the past more than the future- history, not clairvoyancy. Hopefully the winds of change will blow more cleanly. The N.S.W. Public Service is a bit like a rusty weathercock. It moves with opinion then it stays where it is until another wind moves it in a different direction’