European Enticement.

Flying nonstop across the Eurasian landmass had great appeal at the time although airfares at that time were still awfully steep.

As was the excessive appearance of some airline hostesses. You had to make sure to fly Foxy Lady,

not her bushy tailed vulpine sister.

So going overland in my seven-league boots, supplemented by a few student concession flights, would allow me to take in many exotic lands and peoples at more or less the same cost. My earlier safari had taught me how to start on the logistics and hazards of travelling in Asia at a basic level. The bare necessities. My plan would be to sample some of India’s spice, courtesy of her railway system leading me to hop it to the ‘schoolhouse in the clouds’ in Nepal and the archaeological treasure of Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan.

After these I would pick up the Hippy Trail proper and head off into the wide blue yonder.

A Train of Impressions

Calcutta provided the inevitable culture shock and assault on the senses and sensibilities that no amount of reading could prepare one for. The sheer mass of humanity. My first morning there, I was awakened by it’s smell. Hardly a reassuring place, I could not but be wrenched at the sights and sounds of the unparalleled human poverty and degradation.

Destitute men, women and urchins living their private lives in the street, in unimaginable poverty and often abject squalor, some disfigured by accident, amputation or disease, imploring eyes and outstretched hands asking for “Baksheesh”. Crumbling tenements, hygiene horror, sleeping masses in every nook and cranny, wrapped in cloth like corpses, touts and panhandlers wherever I trod, overflowing garbage clumps, rats in a park better fed than many people.

At the same time people seemed happy in this colourful madness, smiling at you and acting kindly to each other. Above the din of the incessant traffic ,horns blaring, cows mooing, passengers clung to the outside of buses.

Poor people pedalled languidly on upright bicycles, marching with their briefcases through the dust. People washed clothes in open drains and showered from hoses. Everywhere you looked there was industry lined on either side of the street, everybody on the move.

Commerce hummed in tiny spaces with people buying or selling something. Sidewalk vendors hawked their wares. Chickens in wicker baskets were on display at the side of the thoroughfare.

Stall-holding chefs serving up their own tasty specialities, cobblers mending shoes, pavement barbers, , customers haggling vociferously. The smell of spices, dust and thronging humanity hanging over everything. Sensory overload. Plunging into the bum to bumper pandemonium of hand pulled rickshaws, stray animals, pedestrians buses and honking cars and pedestrians, I realised all you need to drive in India is a horn, a good set of brakes and nerves of steel. It was pure chaos but – it worked! People got around.

I toured the city threading through and breaking free of the snarls of traffic, looking to change some money in a place where the dollar remained more valuable than oxygen, of which there was precious little.

At every turn I came across the beauty hiding behind it’s poxy camouflage. India is absolute disorder but soon you begin to think of it as vibrancy, life and a riot of colour.

Later I ventured into the meat hall at Hogg Market. Butchers in blood-stained vests hacking away at bone and gristle, hunks of raw mutton hanging from the ceilings, entrails set out for inspection on marble slabs, bluebottle flies buzzing around them, I was put off meat for some time. Fortunately superb vegetarian food was widely available in this crazy city which more than made up for it. The virtue of vegetarianism was made apparent to me as much by this offal offering as any conscious ethical decision like Gandhi’s.

I teamed up with Carol Henderson, a Sydney public school teacher, heading the same way. It didn’t take long to find the hidden jewels. An aging Anglo-Indian lady came up to us in the street and invited us to have Christmas dinner with her and her family. Carol and I were treated as honourable guests and met the lady’s granddaughter whose beauty to me surpassed that of the Taj Mahal.

I asked our host, ‘Why are there so many beggars in Calcutta, some with amputated arms outstretched?’

She said, ‘Calcutta isn’t known as ‘The Dying City’ for nothing. That’s because much of it’s industry was killed off. For at least two centuries Bengal used to be the centre of a thriving textile industry. The forebears of these beggars would have been involved in it either in production or trade. Our handloom weavers produced some of the world’s most desirable traditionally woven fabrics. She showed me some of her heirloom dresses, laying them out on the dining table. ‘These fine long muslins have been in my family for generations.’

‘Covering a multitude of shins,’ I said.

Holding a simple white dress against her granddaughters figure she said, ‘This one was made locally. As you can see the fabric is perfect for clothing in hot countries. Feel how fine it is. It’s so delicate it can fit through a finger ring.’

‘The British must have snapped them up to send home.’

‘That’s not just what they snapped. These objects of desire and symbols of luxury were so cheap that Britain’s own cloth manufacturers conspired to cut off the fingers of Bengali weavers and break their looms. To stop their import, duties were imposed. They flooded our market with their own cheap fabric – cheaper even than poorly paid Bengali artisans could provide. Now this embroidered gown,’ she said indicating another, ‘came from cotton fabrics produced on the looms of the west of Scotland.’

‘India could still grow cotton.’

‘India still grew cotton, but Bengal no longer spun or wove much of it.’

‘That must have led to a lot of unemployment.’

‘Weavers became beggars and so it passed on to their descendants through the ensuing years. People lost the skill of their fingers, and only the roughest-made country cloth still found a market among the poorest.’

What do you look for now in your everyday clothing?’

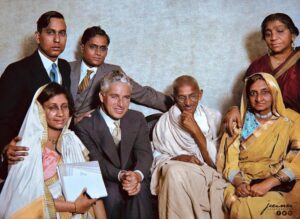

I try to wear clothes handcrafted from traditional Indian cloth made on the handloom. That’s my small part of boycotting imports. This is what loin-clothed, worldly as well as otherworldly Gandhi at his spinning wheel encouraged us to do. For him weaving every morning was his way of saying ‘I believe in practising what I preach’.

‘That’s just what he told Charlie Chaplin when they met in London,’ I said, ‘brought together by a shared understanding of the struggles of the poor and the working classes.’

When Chaplin asked about his views on machinery, Gandhi said: “Machinery prior to now has made us dependent on England, and the one method we are able to rid ourselves of that dependency is to boycott all items made by equipment.”

Gandhi was of course referring especially those machines he saw as robbing Indians of their livelihoods.

Chaplin’s question had delighted Gandhi who explained to him in detail why the six months’ unemployment of the whole peasant population of India made it important for him to restore them to their former subsidiary industry.

“Is it then only as regards cloth?” asked Chaplin.

“Precisely,” said Gandhi, “In cloth and food every nation should be self-contained. We were self-contained and want to be that again. England with her large-scale production has to look for a market elsewhere. We call it exploitation. And an exploiting England is a danger to the world, but if that is so, how much more so would be an exploiting India, if she took to machinery and produced cloth many times in excess of its requirements.”

Chaplin then asked what Gandhi’s view on machinery would be if India were to become self-sufficient: “Supposing you had in India the independence of Russia, and you could find other work for your unemployed and ensure equitable distribution of wealth, you would not then despise machinery? You would subscribe to shorter hours of work and more leisure for the worker?”

‘Certainly,’ was Gandhi’s answer.

Chaplin had understood Gandhi’s position immediately.’

‘Why do you think he grasped it so quickly?’ asked our host.

‘The reason Charlie found that they were on the same page was perhaps his freedom from prejudice or prepossession and certainly his sympathy. Both genial, unassuming men came from the people and lived for the people,’

‘Do you think it was impactful for him in any way?’

I recall clearly reading how impressed he was watching the paradox of ‘this extraordinarily reasonable man, this most entertaining person, together with his astute legal mind and his profound sense of political actuality, all of which appeared to fade in a sing-song chant. Their meeting was the direct inspiration for Modern Times, his film about the dehumanising effect of automation.

Meantime it was time for me to get my own chakras spinning. My official exercise was to have my student card accepted so that I would be able to travel the Indian railway system 3rd class at the concession rate. This involved a whole day going to offices where clerks knee deep in memoranda shuffled papers, clattered away tip- tapping typewriters, plugged along under tardy turning ceiling fans. These merely redistributed the hot, moist air around every corner of the room. Bundles of paperwork, trussed in red tape at desks were piled high. Every detail of every piece of paper was being hand-written with fountain pens and the ink carefully blotted. An element of distinction and authority was added with a wax seal.

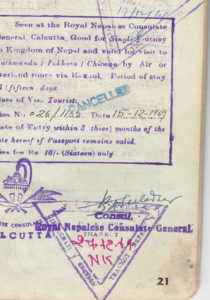

To describe the travel in steerage this entitled me to as ‘no frills’ is an understatement. Padding and legroom on the ‘hardseaters’ went by the board. They were as comfortable as a bed of nails. There was no room to swing a rat. However it was definitely economical and it sure beat having to thumb rides with oxen carts and overcrowded cars on unruly Indian roads. So it was I headed to the Nepal. After the cascade of other bone-weary eyed passengers tumbled out of the train at the border, I looked for a bus to nearby Birganj from where I could fly to Lukla via Kathmandu.

Wish Fulfillment.

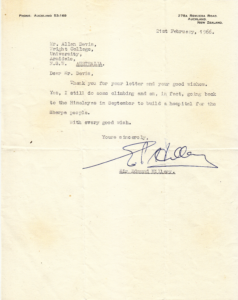

Noting the footprints of other trekkers as I climbed through the Sulo-Khumbu region, famous for its sheer beauty and the friendliness of its Sherpa people, brought to my mind the man these people see as their godfather. Edmund Hillary, whose grandeur matched those of the surrounding masses, left his footprint in a major way. He had told me he was still climbing, a practice he had picked up in his native New Zealand after he had left the Air Force. As is well known he was the first to reach the summit of Mt Everest with Sherpa Tenzing Norgay. He told me about the hospital he was building up here for the Sherpa people.

The brilliantly eloquent answer given to people who ask why climbers scale mountains is “because it is there”. It’s the same answer I normally give for going round them. But on this occasion I had a special reason to go up . My objective was to visit both the hospital and the school Hillary had set up.

Reaching the lovely villages of Khumjung and neighbouring Khunde, home to the Sherpas who had accompanied him on his ascent, involved first hopping from Kathmandu to the-gulp!- razor scrape Lukla runway which faces a cliff.

I had chosen to sit in the tail end of the plane. I’d never heard of one backing into a mountain.

‘Do planes flying here crash often?’ I asked as we approached the runway.

‘No, only once.’

The flaps of our plane were set to full down and it slowed to a little over stall speed..

‘Wow, this is some short runway,’ I said wiping my brow, ready to put my head between my knees as the plane screeched to a stop, tyres smoking.

‘Yes,’ agreed a fellow passenger, but look how wide it is.’

After touchdown I put on my seven league boots for the journey ahead. A trek of several days moving up and down these lower reaches of the ranges. This necessitated some strenuous and vigorous hiking and climbing on my part. Valderi, Valdera!

In this invigorating air, my tank topped up with boiled eggs and chocolate, I replenished the at least 6,000 calories I burned each day.

The trail took me through wooded pine scented hillsides populated by brilliant red rhododendron, magnolia, birches, and giant firs, decorated with lichens and mosses, boulders standing in between, dappled in the filtered sunlight. The narrow sometimes crumbling paths took me past terraced fields hugging the hillsides, laden with potatoes, barley and roses, orchards of apple trees and lush meadows with grazing yaks, bells aringing, ting-a-ling-a-ling, ting-a-ling-a-ling.

It took me through a rich tapestry of numerous small villages, all sturdy stonework with colourful roofs, monasteries, religious icons. The tap tap of masons chipping rocks into neat cubes for walls and foundations was a constant sound. As was the water. Wherever my group were, we could hear it in the distance, roaring and churning . Crossing a variety of remarkable suspension bridges floating at dizzying heights over rushing milky green torrents was another high point of the trek. I hung onto my hat crossing as the wind whistled along the valleys.

The nearest roads being about fifty miles south of Lukla, muscle power had to be the dominant form of haulage. Trains of beasts of burden – donkeys and various breeds of yaks plodding along, heavily laden, ferrying goods around, greeted us at every turn.. You could hear them coming by the bells around their necks. Large holes in the vegetation were reminders of where even sure-footed beasts of burden slipped off the muddy trails and crashed down the side of the mountain.

Then there were the fast breathing porters, men and women, both very young and very old, carrying more oxygen than people from the plains, carrying straw cone baskets with back-crushing weights of wood, food, fodder, fuel, pelts, building materials and so on. Everything but the kitchen sink. With backs bent at the hip they set a steady pace, whatever load they had attached around their shoulders, supported with a headband around their forehead.

At day’s end the group I was with sheltered in windowless lodges with holes in the roofs, from which billowed fluffy columns of smoke. Typically we all sat thigh to thigh on goat skins on the dirt floors full of sacks and baskets holding potatoes, turnips, cornmeal, and stacks of drying yak dung, to be used as cooking fuel. Our black haired, red-cheeked, smiling hosts offered bread, rice and lentil soup filled with whatever random vegetables happen to be lying around at the time, and endless cups of pungent tea laced with yak butter milk, salt and who knows what else.

The old ways persisted in most aspects of my hosts’ daily life. Their washing machine was the rushing river. Their dryer was the sun. The kids used round pebbles as marbles and played catch with potatoes. With rocks and branches, the farmers constructed diversion channels beside the mountain streams to drive the waterwheels that ground their grain into flour.

Putting aside the donkey droppings I had to duck and the bloodsucking, burrowing leeches I had to brush off, the yak track led me through a geography of superlatives. It brought me to a vertiginous panorama of ice and snow clad peaks, including the “Mother of the Universe”, wispy flutes of snow flaking from them. Poking up above the steep sides of the gorges, they soared miles into the heavens, like jagged gleaming teeth threatening to tear a hole in the pure blue sky. Their purity, their silence, their huge imperviousness returned me, craning my neck, to a childlike sense of hand-to-mouth awe. To complete this mystical scene, the air sparkling with ice crystals, high above a griffon glided majestically on the thermals, its vulturous wings resembling giant black fangs.

On the last leg of the journey up and up I went, step after step, each one asking tough questions of my thigh and calf muscles. Pausing every now and then, hands on knees, I bent over and strained for breath. My sugar level threatened to fall, my groin was aching, my knees were begging for mercy and as we moved higher and higher I had to heave my quivering, leaden left leg up with my hands just to keep it moving. At last the ground suddenly levelled off and the tops of buildings rose into view. We’d reached Khumjung and I could still just about stand upright. Just about.

On the way to the Everest base camp, Khumjung, sitting in a high valley, is a point of departure for scaling the heights of Everest and the roof of the world. Reaching the village was just a warm up for some of the serious mountaineers who would acclimatize before setting out for the camp. Reaching there was to be higher than on a lot of mountains but like they say, the Himalayas begin where other mountains end.

Having arrived at my destination, that evening I was rewarded with a sunset on the giants to the north. The earth’s shadow crept up the mountainsides, night pressing on rapidly, the distant summits glisten warmly in the final glow of sunlight. Everest, Lhotse and Ama Dablam all turned to gold, then red then pink while streaming snow from their summits. At last the lights went out and left a momentary radiance in the atmosphere, a purple hue. In that short time between light and darkness the world was still and silent and peaceful. In the south the valley we’d come up filled in with evening cloud, swirling around and up and down the mountain slopes like a slow motion tidal wave. Come morning I was treated to yet another splendidly spectacular display with blazes of orange as the sun rose, casting the white Himalayan peaks in a fiery glow.

The school at Khumjung, the jewel in Sir Ed’s crown, was a simple affair, but it was life changing for the Sherpa people. ‘The school satisfies a deepfelt need,’ the schoolmaster of the Khumjung primary school told me. One elder put it to Hillary this way: ‘Our children have eyes, but they are blind. Therefore, we would want you to open their eyes by building a school in our village of Khumjung, Sahib,” he said. “Of all the things you have, learning is the one we most desire for our children.” They want to read and write so much. So much, so they spend ages each day walking up and down hillsides from surrounding villages on rock strewn mountain trails. In the monsoon, they hoof it in the rain. In winter, they hoof it in the snow.’

‘They certainly keep their eye on the ball,’ I said, observing their field and batsmanship. .. A game of cricket was in progress when I turned up.

“Those boys out there all want to be the next Don Bradman,” he said as we watched them tallying runs on the school’s hard-mud playing field. ‘Sir Ed introduced them to his legend and his sport. Although this landlocked strip of land was never a British colony like India, cricket still managed to make its way up the mountains.’

I looked in on one of the two the aluminium clad classrooms built mostly with Hillary’s own hands himself. Nothing more than a few benches with a black board at the front, the kids inside were reading quietly and intently before rattling off questions of their teacher. As parents gave priority to their sons, there weren’t many girls. Their eyes lit up when I was introduced and they surrounded me asking questions about Australia. Apart from their common love for cricket the enthusiasm brimming in the children for the reading and writing contrasted so greatly with that ennui you can often encounter in many of our schools. You don’t need fancy buildings to educate people.

‘The school and others in the group set up by Bada Sahib, the Sherpa term of respect for Hillary, has enabled the people to develop their skills and preserve their culture’, he said.

‘I sent Sir Ed my good wishes with regard to this success for which he thanked me .’

His whole contribution has a lot to do with wishes. He once asked a Sherpa elder if he could do anything to help the man’s village. The man replied affirmatively and from that moment Sir Ed became the man who granted wishes.’

Before entering the small stone hospital at Khunde, Khumjung’s ‘sister city’, I stopped to observe the industry and craftsmanship of a trio of men carrying out stonework along its wall. I then admired the educational drawings about health, child care and sanitation posted outside the clinic. Most of the patients are illiterate so simple drawings showing such things as how to clean their teeth got the message across. An increase in dental decay had followed contact with the outside world and discovery of the sweet tooth.

‘The hospital carries out both curative and preventative measures’, the volunteer doctor told me. These have had a lasting impact on the hard lives of the Sherpa people. The hospital spearheaded the drive to eliminate the threat of smallpox here. It introduced iodine to help eradicate goitre, which was widespread until recently.’

‘Are these modern medical treatments accepted by the populace?’

‘Yes, by and large. but that has not stopped people from a continued reliance on herbal medicine, on faith healing, and on shamans . When it comes to medicine, they are openminded. They come in here and get vaccinated against measles or polio, and then they go to the monastery and get an amulet from the lama to ward off the same disease.”

‘Hedging their bets.’

‘They are deeply invested in both traditional and western ways’, he said, pointing to one of the nurses. ‘This young lady is training to become a nursing sister. She takes her turn with others to work here without financial payment. It’s the same with those men you see outside repairing the wall. Sir Ed stresses the importance of self help.’

As with the school, the involvement of the locals in the running and upkeep of the hilltop hospital was clear.

The doctor drew attention to what Sir Ed once said: “ ‘I’ve never done anything that they’ve never asked for. It always comes from them’

I asked him ‘What is the most important thing remaining to be done here?’

‘You might think I would say that health care is the most important thing to be done. But no, education is number one. It opens up a world of possibility and it’s essential for us to communicate information and ideas.’

Having doubled back downhill, I was reminded of his work when taking off from the Lukla runway built on a daunting slope, at an angle of 12 degrees uphill because of the lack of flat ground. The airstrip was paid for by the Hillary Trust to give the Sherpas better access to the outside world.

Like Pearl Buck, Sir Ed helped to foster better understanding between people from East and West. He summed up his work thus: “The most worthwhile things I have done are the serious projects for the mountain people of the Himalaya.’

Like Pearl Buck he benefited people other than his own and became one of them.

Down from the Mountains.

In Australia the era of steam engines had ground to an end as I was growing up, but not so in India. The sounds of the gigantic locomotives, objects of high romance, chuffing, chugging, whistling, sending up billowing plumes of steam, churning steel, wood, and dust relentlessly, generating wind, soot and smoke, wheels clickety-clacking over the points, the jog and sway of the clanking carriage, and the heavy noise from the puffing billies crossing iron bridges have kept playing in my head ever since.

The smell and prickle of coal dust on my skin have tarried in my pores long after. As have remained in my mind’s eye fleeting scenes from outside the doors and open windows of my carriage: passengers on the adjacent trains,

cows lingering on neighbouring tracks, friends chatting in huddles by them, pyramid-like salt mounds drying in the sunshine, ladies banging washing, men squatting in circles playing cards, the backs of people’s houses so close up you could see what they’re eating for breakfast.

The railway is an institution in India and a world of its own.

It began and ended at the Indian railway station. A locomotive pick and mix of sizes, speeds, shapes and colours – that was just the passengers. Swarming with life, an army of bawling, crowing tea and food wallahs was always on hand offering them their products. The tea makers boiled and stirred, teeming and ladling, adding their particular blend of ginger, garam masala or saffron to give their tea its own aromatic identity. They served it in disposable clay vessels which patrons threw down on the ground after they finished. Walking along the platform involved wading through their smashed fragments which littered it.

I felt the hardship of the porters in their iconic crimson uniforms carrying heavy suitcases – often balanced on their heads.

The station was an ideal place to meet people. Well goodness gracious me, someone with a veddy Peter Sellers accent would invariably waltz up, eager to engage in conversation to improve their English and, shaking their head from side to side, satisfy their boundless curiosity about the wider world.

The travellers advised me how to best make my journey. They knew so much about trains, not because they were trainspotters or enthusiasts, but because trains were the mainstay of Indian travel. Roads were a dangerous adventure, planes the reserve of the privileged. People knew the best trains and the worst, the quickest and the slowest, the routes, the numbers. ‘ Namaste, You need to ask for the Gorakhpur slip coach on the 9 Up, that way you don’t have to change at Jhansi.’ ‘Never take the Upper India Express. Oof! It takes for ever.’ ‘Try the tea stall at Gwalior. Kapoor’s. The tea is really bang up.’

They knew about outer signals, loop lines, up trains and down trains. They knew the difference between different categories of train: mail, express, fast passenger and passenger. They pored through their copies of the railway travellers guide, ploughing through the tiny grey print of its timetables to determine how the family and its several trunks would reach their destination. The guide listed every train in India from everywhere to everywhere else, noting their arrival and departure timings at every station, including minor wayside halts. They were, in this aspect of their knowledge and behaviour, like Victorians.

The station was heaving. Everyone seemed to be on the rattletraps. Four hours after mine was due I was riding again, introduced to an endless hustle and bustle of people from a vast array of ethnic religious and economic backgrounds.

The crowding and the chaos left me with the impression that most everyone in the country was trying to cram into the same train as me. Dodging and shouldering one another to board, lugging boxes and bed rolls, they piled into the compartments, full to the gunnels and scooched down in the corridors. Tightly packed bodies twisted and bent to be shoehorned into every crack and crevice of the train car. There seemed to be a distinct shortage of guards, baggage handlers and conductors. A case of not enough chiefs and too many Indians.

I learned the main rule that Indians learn about life: ‘There’s always room’.

I impressed my fellow travellers on one occasion by picking up a guy trying to nest in the luggage rack and depositing him there. Riding the rails, the relaxed anonymity proved to be a perfect setting for travellers to reveal to me perspectives on their world.

After arriving back in northern India from Nepal I got on a train heading for Delhi. I struck up some lively conversation with others in my compartment. One I remember was an American hippy with a smiley face button. ‘I’m studying ancient Hindu texts’, he said. ‘This is it’s classical guide to a virtuous and gracious living,’ he declared, pulling out his copy of the ‘Kama Sutra’ from his rucksack. With all the other passengers in the compartment sharing the insight of this illustrated version, I’m sure it ended up putting them in an awkward position.

I ended up putting another fellow passenger, a misty-eyed Raj romantic in an equally awkward position. I engaged in conversation with this brolly bearing anglophile, dressed most impractically for this hot, humid environment in a worsted woollen three piece suit and pointy beige shoes. He never loosened the buttons of his coat even when mercury crossed the thermometer’s 110F mark.

As well, there was the passenger with a strong sense of Gandhian attachment. Unsurprisingly he was wearing a white Nehru jacket with it’s short stand-up collar.

Tea and travel being synonymous in India, when the train halted outside one of the stations on the way, us passengers took refreshment from the railway tea stall while the anglophile kept his gladstone bag well clear of the open window. On the platform the chai maker was busily brewing and serving. After we placed our orders through the open window to his son, the boy manoeuvred his way to the stall and back to us through the crowd with his little tray of clay cups.

As we sipped our tea we were treated to the most basic percussive offering. Two beats on the station bell, in this case a length of old rail struck with a hammer, told us a down train on the down line was going the other way.

‘This drink is a staple of Indian life,’ said the anglophile, ‘Just as it is for you British. It’s our national drink, to all intents and purposes.’

‘Well I’m not British, I’m Australian,’ I said aware that I was legally a British subject whatever that meant in practice.

‘Same difference’

‘Actually no, but I agree with you on the importance we all place on tea.’

‘ ‘Great minds think alike,’ he said raising his cup towards me, ‘especially over a cup of tea. And to think tea didn’t come from India. It was the British who brought it here. It was the Honourable East India Company who established the tea trade in India. British tea merchants eventually spread it’s consumption here. One of the ways they would do this was that they would go to railway stations like this one and serve free tea and milk.’

‘You make them sound all so generous,’ said the republican, ‘They just pushed it to expand their market. To end their dependence on Chinese tea, the Company set up plantations here. This voracious monster felled vast forests, stripped the tribals who lived there of their rights, and then paid Indian labourers poorly to cultivate the cleared areas. Once the tea was ready, it was shipped off to Britain or sold internationally. The little bit left in India was too expensive, until the Great Depression. Weak global demand and the potential of the big Indian domestic market finally let Indians enjoy the delights of the drink they produced.’

That’s when you got addicted,’ I commented.

‘Throw in our sugar and they had us hooked. We don’t have them to thank for that. We Indians discovered how to crystallize sugar way back around the time Jesus was preaching in Judea. Way before the British brought slaves to the West Indies to produce it.’

‘Whether West Indian sugarcane producers, Indian tea pickers or Australian sheep farmers, we’re all freemen these days, said the Empire loyalist. ‘As members of the British Commonwealth we share a common bond. We share the legacy of this great civilizing culture. As Edmund Burke put it, these were, and I maintain still are, ties ‘which, though light as air, are as strong as links of iron.’

‘As light and strong as the chains that shackled those sugarcane cultivators you mention.’

‘Had it not been for the British there would never have been the entity called India.’

‘Fiddlesticks! As far back as emperor Ashoka, about 300 BC, large parts of the subcontinent enjoyed cultural and administrative unity.’

‘I don’t know what happened back then but the sub-continent became divided later. The British provided Indians the tools and institutions needed to hold the union together and run it.’

‘There were limits to how long they could hold it together. In their entire two centuries rule, they made up no more than a tiny percentage of the population. And, yet, for most of that period, no Indian was allowed to join the Indian Civil Service, in part because the British could not bear to take orders from a brown man. Britain’s policy was not to unite but to divide and rule.’

British rule may not have been better than the despots of earlier empires but it wasn’t worse.’

‘Few kings or dictators ever rule to benefit their people. We’re constantly reminded of the millions who’ve perished during the purges and famines of Stalin and Mao. Please consider also India’s famines during the Raj: Between 1770 and 1947, the oppressed suffered at least eleven major ones and many minor ones, resulting in thirty five million deaths.’

‘You can’t blame the British for that. Famine has long been a part of life in India.’

‘As the effective governments the Company and later the Raj were responsible for saving people from them. Their response of inaction amplified the effects. These corporate raiders turned the famine in the late 1760s into a massive humanitarian disaster. While the Company nabobs were back in Britain buying stately homes, filling them with silver, wine and art, throwing parties, balls and entertainments, the people of Bengal who were paying for all that, were experiencing some of the most appalling conditions imaginable. Their rich region was bled dry. Meanwhile the Company watched and recorded everything. They raised the taxes on agricultural produce, they banned the hoarding of rice and grain, traditionally used to tide over the population through periods of scarcity. They ripped up some of the food crops to plant much more profitable crops such as indigo, and opium for the Chinese market.

‘Misery loved the Company there as well.’

‘Some of their minor officials even speculated and profiteered from the sale of rice and grain, selling it at grossly inflated prices.’

The empire’s record of forced migration is no better. To be an indentured Indian labourer was to enter a life-and-death lottery in which your chances of survival were significantly worse than those of a shackled African slave. None of this is anything to be proud of. Can you justify any of that?’

‘I can’t. No one can. But no one can deny the positive heritage. Not everyone threw their caps in the air in 1947. My family have been associated with the British for generations and I want this to continue. I attended a British public school in Delhi which gave me an entrée to world culture. I spent my best days in that wonderful country Britain. I became such good friends with so many that this independence thing hardly comes to my mind. The British helped shape the attitudes and tastes of the tens of millions of English-speaking Indians. We learned from the best. How’s that for openers?

‘Sure they brought cricket to both our shores. But didn’t they take our polo back to their little island reserving it for their own brahmins? Granted man does not live by chapati alone … but he doesn’t live long without it.’

“I can only speak for myself. I’m passionate about playing and following the gentlemanly sport. So much of what we take for granted in our daily life – the books we read, the way we eat, sometimes the way we dress, our habits and cultural allusions – have come from their time here, from British institutions and the English language,” he said.

‘One thing is undeniable They brought trains to India and left an expansive railway system far in advance of any other Asian nation. Apart from gifting Indians a fantastic railway system, an advanced legal system, parliamentary democracy, free trade, advanced medicine, technical education, what more can Indians accuse the British of denying them?’ he asked rhetorically.

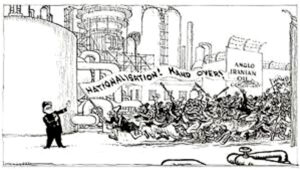

‘A progressive taxation system-one without a gun raised to their head. Now let’s be serious. They denied us entry to the British market for their manufactured goods. They denied us the ability to share in the great prosperity being made from our efforts. Lets look at the railways since Lets look at the railways since it’s in their tracks that we’re travelling along right now. Sure they were first conceived of by the East India Company, but like everything else in that firm’s calculations, the network was for its own benefit. The Company only did what was best for the Company.’

‘The Company did what the company needed,’ said the loyalist. ‘Their priority was to construct such a network for their operations. There was no effective central government to provide such infrastructure.’

‘The network was set up for the commerce, government and military control of the country. It was established to more effectively move goods and extracted raw minerals to ports for the the maritime superpower to ship home to use in their factories. And of course to move troops more effectively to wherever they were needed to quell rebellions against their colonial rip off.’

‘You don’t see it as a gift to the people of India. Think of the industry this commercial titan created. Don’t you see it as a blessing?’

‘Hardly. Any social benefits were unintended. In their very conception and construction, the Indian railways were a colonial scam. Any benefits that accrued came only by accident. British shareholders made absurd amounts of money by investing in the railways, where the government guaranteed returns double those of government stocks, paid entirely from Indian, and not British, taxes.

‘So, if the railway company couldn’t achieve that return on its own, then the government made up the shortfall from its revenues,’ I suggested.’

‘It was a perfect sellers market. And a splendid racket for Britons, at the expense of the Indian taxpayer. The railways were financed by an elaborate and shonky scam that enriched British investors by inflating the cost of Indian rail track to twice that of Australia and Canada.’

‘Do I understand you correctly? A mile of Indian railway cost double the same distance in the equally difficult terrain of Canada and Australia.

Correct. It was a licence to print money. Private enterprise at public risk. Socialism for the investors.’

‘Who presumably weren’t Indian.’

‘No surprises there. Only one percent of railway shares originated in India. Most of the rest came from small shareholders with addresses in southern England: from bankers, barristers, spinsters, retired army officers and people known simply as ‘gentlemen’. Their individual holdings were not large but the total invested meant that India’s railways represented one of the 19th century’s largest flows of money between continents.’

‘The railways enabled Indians to travel around their country,’ said the loyalist, ‘to bring families together and to inadvertently unite the country, ripe for independence.

‘The movement of people was incidental, except when it served colonial interests. You might think this train has smelly, grotty toilets but spare a thought for the poor Indians herded onto hard wooden benches. The trains they were on had a total absence of amenities.’

‘You must admit the fares today are very low.’

‘They might be now now but back in the Raj, Indians still paid the highest third-class train fares in the world. Indian freight rates, in comparison, were some of the lowest.” he said.

‘They were democratising vehicles, providing a meeting place where Indians could mix with the British and Europeans in an atmosphere of mutual understanding.’

‘‘They are now but during the Raj there were compartments reserved for whites only. Indians found the available affordable space grossly inadequate for their numbers.’

‘The network created jobs for Indians.’

‘Indians weren’t employed initially in the system. The prevailing view was that the railways would have to be staffed almost exclusively by Europeans to “protect investments”. This was especially true of signallers, and those who operated and repaired the steam trains, but the policy was extended to the absurd level that even early this century all the key employees, from directors of the Railway Board to ticket-collectors, were white men – whose salaries and benefits were also paid at European, not Indian levels and largely repatriated back to England.’

‘The British must have encouraged the low paid Indians to build the trains.’

‘You’d think so but it didn’t work like that. Railway workshops were established in the eighteen sixties to maintain the rolling stock, but their Indian mechanics became so adept that in the latter part of the nineteenth century they started designing and building their own locomotives. Their roaring success increasingly alarmed the British, since the Indian locomotives were just as good, and a great deal cheaper, than the British made ones. Come the new century, therefore, the British passed an act of parliament explicitly making it impossible for Indian workshops to design and manufacture locomotives. Most locomotives came from England and other industrially advanced countries, but none were made in India after the Act.’

‘So by stifling production of engines at home, Britain retained its grip on the technology as the supplier of all its equipment, which meant once again that the profits were repatriated.’

‘They controlled everything. After independence, 35 years later, the old technical knowledge was so completely lost to India that the Indian Railways had to go cap-in-hand to the British to guide them on setting up a locomotive factory in India again.’

‘So you see the British policy as one of economic sabotage.’

‘It was from the word go designed to deny India the opportunity to develop it’s own industrial base.. The East India Company smashed India’s advanced textiles industries, literally by demolishing factories and imposing huge tariffs on exports to Britain. In doing so, they turned a manufacturing, shipbuilding nation into a source of raw materials with little scope for value adding industries. India was reduced by the depredations of imperial rule to one of the poorest, most backward, illiterate and diseased societies on earth by the time of independence in 1947.

‘The British gave India democracy, a free press, and the rule of law. Don’t these fruits of European Enlightenment, these expressions of a higher moral and social order count for anything?’

‘However strongly they denied to Indians – as they had to Americans before 1776, ‘the rights of Englishmen’—the British did instil a sufficient dose of the ethos of democracy into their former colonies. So much so it outlived their tutelage. But the actual history of British rule does not suggest this was either policy or practice. A democracy cannot function without a free press and just law. Neither truly existed under the Raj.’

‘Can you deny the British were the first to establish newspapers, the lifeline of every literate individual in India’

‘These catered to a small English-educated elite first, and large audiences in the vernacular languages later. It was this proliferation that led to their being censored by the Company.’

‘How was this carried out?’ I asked.

‘All newspapers were subjected to scrutiny before publication. Under subsequent controls, publishers were required to provide a hefty security deposit, which they would forfeit if the publication carried what were considered inflammatory or abusive articles.’

‘Was the British-owned press treated the same?’

‘Their racism was not subject to the same restrictions, the most infamous being the draconian law passed after the First World War. This suspended basic civil liberties for those suspected of plotting against the Empire. It meant you could be imprisoned without trial for up to two years simply for having what was considered a seditious newspaper. This measure and the protests against it led to the massacre at Amritsar.

It provided the first nail in the coffin of the Empire.’

‘How do you judge the justice system under the Raj?’

‘The justice system in India was even more discriminatory. For instance, If you, a British subject, were to have gotten angry with me, your Man Friday, and pushed me off the train to my death, you’d have got six months in jail and a modest fine. But an Indian convicted of the attempted rape of an Englishwoman was sentenced to twenty years. ‘The death of an Indian at British hands was always an accident, and that of a Briton because of an Indian’s actions always a capital crime. The imperial system of law was, pure and simple, an instrument of colonial control.’

‘ The dark twin of the British success. Thank goodness that all came to an end.’

‘Regrettably the legacy remains. The British legal system has left India with an unenviable judicial backlog. There are still cases pending that were filed during the days of the Raj.’

“The court system, the penal code, the respect for jurisprudence, and the value system of justice—even if they were not applied fairly to Indians in the colonial era—are all worthy legacies,”

‘That’s as may be. But in the process Britain has saddled us with an adversarial legal system, excessively bogged down in procedural formalities, which is far removed from India’s traditional systems of justice.’

‘They acted graciously in defeat. They were benevolent by giving us independence.’

‘Freedom is never given’, replied the republican. It has always been wrested from the oppressor.’

Allow me to compliment you on your facility for the English language,’ said the anglophile. ‘Doesn’t that confirm that at least in one respect you’ve benefited from their presence? The Company made English the world’s predominant language.’

‘The British made it absolutely clear that it was only taught to serve their own purpose. Lord Macaulay wrote and I quote: ‘We must do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons Indians in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals, and in intellect.’ This is the same politician who also said, ‘A single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.’

‘Macaulay envisaged an education system in India where the children of the local elite would be introduced to modern scientific knowledge via a mastery of English. He believed it couldn’t be done via classical Indian languages. It was not intended for all the masses but would filter downwards from the cream of society.’

‘The notion of the local subjects fostered under the Raj and reflected by Macaulay was more racist than that under the Company. It was that ‘They wouldn’t be ruled by us if they weren’t inferior’. As ruling them became more important than trading with them, the imperial administrative class saw themselves as superior and more civilised. They saw themselves as increasingly detached from barbaric India whose people were incapable of elevated thought. With the shift in operations and purpose from trading house to imperial administration, with the stripping away of Company monopoly of trade, they could no longer personally ‘go native’.’ European customs and manners were increasingly emphasised amongst the white elite. They strove to recreate their old British lives, eating British food three times a day, planting British seeds in their gardens and wearing ridiculous British clothes as they went out in the hot Indian sun.

‘Living in this anglicized bubble appears an obstinate, desperate attempt to keep a little piece of Britishness alive in this huge sub-continent.

Yet looking at you with your tie and impeccable English,’ I said turning my head towards the loyalist, it appears that Macaulay’s Westernising vision has been realised.’

‘It is evident that Macaulay’s understanding of India was awful.’ I said. ‘He was undoubtedly a colonial apologist and racist. It’s commendable you have the ability to understand this mindset and reveal it so convincingly.’

‘Indians seized the English language and turned it into an instrument for our own liberation. My whole point is that this was to their credit, not by British design.’

‘You articulate a savage condemnation of that colonising nation. Yet you don’t appear to bear grudges against the British, Swami,’ I said, addressing him with the title of respect conferred on the learned, ‘How do explain this lack of rancour?’

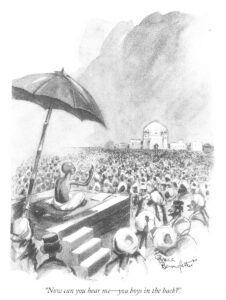

‘The opposition to the British was non-violent. That was the strategy Mahatma conveyed in his mass gatherings.

This is the key to understanding why there is not more resentment and anger between the two nations. Let me repeat the answer of our first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, when Winston Churchill asked him why he didn’t feel more bitterness about all the years of imprisonment he’d suffered at the hands of the British.

‘I was taught by a great man, Mahatma Gandhi, never to fear and never to hate,’ Nehru is said to have replied. We should forgive because hatred is a terrible emotion, but we should never forget. People can forget too soon.’

The Tracks of Their Tears.

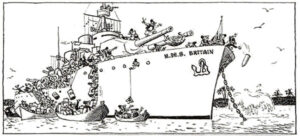

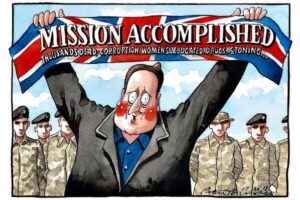

Having rolled across the flat fertile plains of Northern India to Delhi, I would next find myself hurtling down the dusty plains to Karachi via the necessary stop for customs and the walk through no mans land to link up with the Pakistani rail system. This was a major transit route in 1947 for millions fleeing the communal violence following partition. On their way out, the British had facilitated this.

Partitioning the subcontinent into India and Pakistan overnight hastened the mad scramble of displaced people. Trains travelling along this route were jam-packed with people sitting on the roof and hanging from the sides. Millions fleeing the savagery assumed a train ticket would assure them of reaching safety but they were most vulnerable to attack by the rampaging hordes. Easy targets. Bodies littered the tracks.

What was the response of the British Government to this outpouring of hatred and recrimination.?

Their attitude was one of blithe indifference. Nothing was properly handed over. There was a sense of secret satisfaction that, ‘Well, you know, India’s falling apart. We brought unity and they messed it all up. We told them so.’

The massacres loom large in the Indian imagination. The image of the moving train loaded with corpses still haunts the nation. Daily life on the subcontinent has continued to be convulsed by such eruptions of bloodshed and savagery, in marked contrast to that of a golden age in its civilization about which I will now explore.

Charmed

Leaning on his horn, overtaking an obstinate procession of camels and small wooden wheeled carts my taxidriver from the local train station dropped me at Mohenjo-daro. This most extensively excavated site of the 4500 year old Indus Valley Civilization consisted of 400 cities and towns along the Indus River. Mohenjo-daro was its bustling centre. At one time the largest city in the world, it existed when the pyramids were being built and the inhabitants of Britain were still living in the Stone Age.

After checking into a small onsite guesthouse, I made my way over to the site which I would spend the following days poring over. Its onsite museum would be my reference. It preserves a repertory of artifacts and tells the stories of the ruins in large murals. These take the mind back in time showing the vital role of the river in this advanced civilization, enabling extensive trade.

In antiquity the climate was much cooler and much rainier than the present desert suggest. Today’s flow of the Indus 5 kilometres to the west of the site is the Rosetta Stone for the city’s depopulation.

Walking through these deserted streets, I thought of Mortimer Wheeler, one of a handful of noted archaeologists to have yielded its secrets. He was familiar with every inch. In studying pre-history, I regarded his patient achievement as very valuable. In both fieldwork and academic archaeology, the range and standard of his work made him a leading figure of international archaeology in the 20th Century. He was a great popularizer of his subject, particularly on television where I came to see him. Like his friend Sir Max Mallowan, he helped illuminate early societies.

Through his digs Sir Mortimer threw light on life in Roman and pre-Roman Britain and the early civilization of the Indus Valley, like others in early Asia traditionally papered over in extent and importance. Director-general of archaeology in India, he worked to particular effect at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa whose citizens were descendants of early groups of Homo sapiens migrating from Africa.

I told him I appreciated his spectacular ability to present scholarly subjects in easily intelligible terms.

I told this veteran of two world wars, whose first experience of trenches were of those he saw dug for military defence, ‘I wish you and yours the best for your remaining years. Growing old, things can only get better. No longer will your life be in ruins.’

Walking through the main streets and the by lanes of this city, soaking up it’s heritage, I visualized its colourful daily life as it would have been nearly five thousand years ago. The most striking feature was how well organized its builders were. The wide streets were laid out according to a symmetric plan on a rectangular grid. Bricks were baked to a standard size throughout the civilization, being used by master masons familiar with plumblines and water levels to build houses of two or more storeys high, their walls exposed by excavation. Fired bricks had been used for the foundations, unfired for the walls.

The houses of typical brick and timber construction are similar to those lived in today. Max Mallowan pointed out the continuity in the system of weights and measures that would have enabled this construction. The houses feature bathing pools, living spaces and central courtyards and staircases that would have lead to the roof and drainage shutes. The complex water management system of guttering, sewerage and drainage were far more efficient than most of those I encountered on this journey. Each house had had a well tiled bathroom and its own well. Brick containers were conveniently placed for rubbish disposal. At the top of the city was the spectacular communal bath for public ablutions round which there had been a gallery of fountains.

Sir Mortimer had been ‘touched’ by my “charming words” as I had been by his in conveying the wonder of Mohenjo daro and enticing me there. I could feel the same spell he fell under when unearthing its hidden delights. They were in abundance, he noted in an excavation report: “Stratified potshards and other objects were recovered literally by the ton; four weeks after the beginning, twelve loads of selected pottery were sent back to base and more followed. In recognition of his carrying all these heavy, bulky loads he gained the title ‘Sir Mortuary Wheelbarrow’. He mentioned “toys .. which provide an animated account of life in the ancient metropolis”. They had prompted others to conclude these had been cities of children. One of these toys was an artifact in the museum, a miniature terracotta model of a small wooden wheeled cart, just like the ones I had passed in my taxi on the way here.

The cart could well have been the plaything of the Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro, Mortimer Wheelers favourite statuette. I paid my money for a copy of the statuette to the assistant at the museum, a lady dressed in a tunic and trousers, modest by Western standards but pushing the limits set by the local religious hardliners. The bronze statuette of the hoochie coochie girl with her shameless posture and her legs slightly forward as she beat time to the music with her legs and feet exudes a sensuality that is as captivating today as it was thousands of years ago.

Sir Mortimer would say of her in a 1973 television program ‘there is her little Baluchi style face with pouting lips and insolent look in her eye. She’s about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on. A girl for the moment, perfectly confident of herself and the world. There’s nothing like her I think in the world.”

The world in which this free spirit lived appears to have been a pleasant, carefree one with no formal religion, no great differences of income, a fairly egalitarian one. Its arcadian citizens seem to have been a truly liberal people who, unlike us, spent little time and resources on war, on arms and weapons and killing others. Instead they crafted their valuable hoard of metals to make jewellery, tools and exquisite masterpieces of sculpture. Archaeologists believe they produced muslin of the finest weave.

To recreate this world and find my very own Dancing Girl became the object of my pursuit.

Up the Khyber.

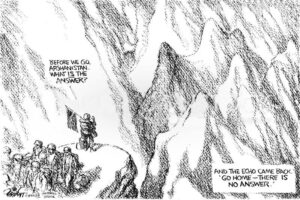

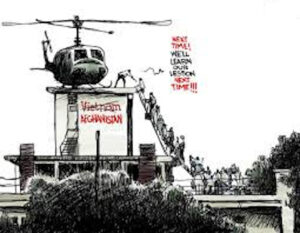

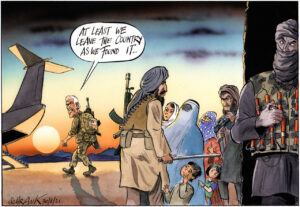

“We have nothing to fear from Afghanistan. And offensive though it may be to our pride, the less they see of us, the less they will dislike us.”

General Roberts speaking at the end of the second Anglo-Afghan war, in 1881 after pulling out of the country following heavy British casualties.

“My dear boy, as long as you do not invade Afghanistan you will be absolutely fine.”

Attributed to Harold Macmillan, handing over the prime ministership to Alec Douglas-Home in October 1963 .

After the flat and baking fertile plains of Pakistan, through tunnels , along hairpin bends I dropped in on the landlocked land of pomegranates.

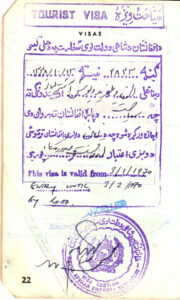

The monarchy’s border itself was practically deserted, apart from a few soldiers milling about in their fatigues. At customs the official there gave me a form to fill out and stamped my passports with barely a glance.

Others were there to drop out. Yet to be struck by the bulldozer of industrialisation, the country’s appeal for young travellers was it’s very absence. A culture arrested in time.

Sitting high in the Hindu Kush, the Afghan capital is overlooked by mighty snow-capped peaks. Once I’d offloaded my bags, I pushed off to take in its sights and sounds. While the cry of the muezzin summoned the faithful to the mosque, I myself headed to the bazaar. It announced itself with a powerful waft of tea, spices and kebab smoke.

I entered the dusty tangle of winding lanes that twisted in and out, intersecting and overlapping to form a jumble of mazes. It was like stepping back into the medieval past. I passed dazzling treasure troves of brassware, spilling out onto the streets with trays and teapots studded in silver grapevines and arabesque design. Stalls were laid out with bountiful supplies of pomegranates and flat breads that looked like snowshoes. Vendors without overheads draped their shoulders with numerous coats. Men sat on the ground against a wall got their hair cut while watching the crowd go by. Beneath a wall of shrieking birdcages, a man in a skullcap mumbled over prayer beads.

There were tribesmen armed to the teeth, pistols in their belts, even swords and daggers. Muskets and bayonets from the three Anglo-Afghan wars were for sale in one stall. The bayonets had serrated edges which meant the victims having to be trodden on for them to be pulled out. On the ‘plus’ side, it widened the wound on the way out!

As I was glancing over these – thinking of the chests the blades had run through, springing a leak like stuck pigs, good times all around – a well groomed man with a neatly trimmed beard came up to the stall and started chatting to me. He was well turned out from head to foot with silver embroidered vest, silk shirt, satin baggy-trousers, green striped chapan coat and astrakhan hat.

‘Salaam,’ he said, bowing and touching his forehead with his hand. ‘Peace be with you. Do any of these artefacts take your fancy? A penny for your thoughts.’

I answered, ‘They must have some stories to tell’, referring to the artefacts on sale.

‘You’re interested in such objects?’

‘I am,” I replied. ‘And in why you speak such good English.’

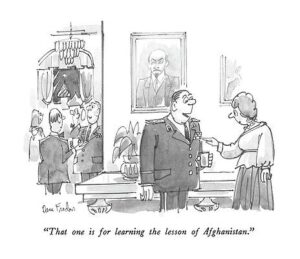

‘ I learned it at school and try to keep practising it. I don’t like to seem deaf and dumb when I speak to visitors. As for the weapons allow me to explain their place in our history. As children, learning to walk we all learn about our jihad against the British, he told me proudly, raising his extended index finger higher and higher into the air as he spoke. ‘In the last century the British were obsessed with the idea that their rival, Russia, was considering invading us. They fretted that our land would be a staging post for an attack on ‘their’ India. They saw it as an immediate threat to British national security.’

’We know this period of mutual suspicion and paranoia as “The Great Game”, I said.

‘It was not cricket. With their military superiority, the redcoats marched in with an imperial swagger, carrying with them every comfort of home.

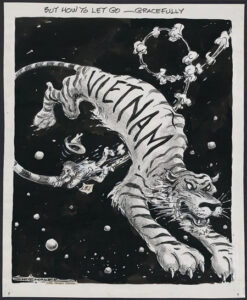

‘Just like the Americans on the march,’ I said. ‘What we see today in Vietnam.’

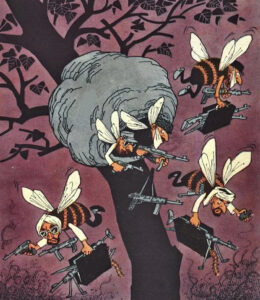

‘The British 16th Lancers even brought a pack of foxhounds with them into Afghanistan in 1839. Not that these could save them. Our warriors are like our keen sighted Afghan hounds.

‘They’re more closely related to wolves than most dogs, I believe.”

‘Absolutely. These sighthounds pursue their prey, keeping it in sight, and overpowering it by their great speed and agility. They will always see out any invading force.

You see, It’s easy to launch an invasion of our country. It’s much harder to get out in one piece. We have fought off invaders all the way back to Genghis Khan. Time has always been on our side.’

‘Fighting an insurgency requires patience and restraint, whereas the better armed invader has to hurry.’

‘The British may have had the clocks but we had the time. It’s not for nothing our country is known as ‘the graveyard of empire’. We don’t take to being occupied easily. And when we are, it’s hard to get our land of stones and men to pay the bill. After all you can’t get blood out of a stone.’

‘The defeat of the British would have been the greatest military humiliation ever suffered by the West in the East to date.’

‘The entire army of what was then the most powerful nation in the world was utterly destroyed by poorly-equipped tribesmen. It seems like the U.S. will suffer the same fate in Vietnam. It looks increasingly like they’ve reached their due date.’

‘What legacy did the British leave on the country?’ I asked.

‘To suit themselves they left it undeveloped. They brought about a series of regime changes and left a small Afghan elite attempting to impose western-inspired ideas and modernity on the country. Yes, you can see young men of the elite here spending cash, talking trash, dressing fine, making time. They copy your travellers and grow their hair while girls shorten their hemlines, but these changes are cosmetic, superficial and futile.’

‘All show and no go.’

‘They may well be forced to go. Resistance to the occupiers has often been expressed through great savagery and fanaticism. This is not the natural way of our people.’

‘That raises the big question, doesn’t it. Why do invaders still insist on trying it on?’

From One Kingdom to Another.

Bordered to the north by the the Soviet Union, sandwiched between the U. S. allies Pakistan and Iran, foreign governments were taking a threatening interest in the country, seeing it as a centre point in the Cold War. The U.S. feared a push south by the U.S.S.R. in search of a warm water port and oil supplies. The U.S.S.R. feared the U.S. was fomenting instability on their southern frontier. Both were jockeying for influence, pumping millions of roubles and dollars into its infrastructure through aid and loans.

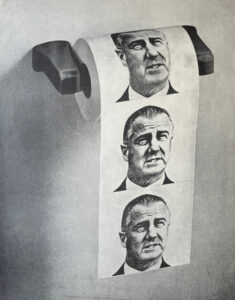

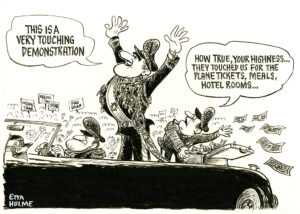

I witnessed the motorcade of Spiro Agnew, the American Vice President, speed by in a flash. I couldn’t see him clearly but knew what he looked like.

He was enjoying R&R from being targeted on corruption charges stateside whilst drumming up support for America’s fighting boys.

He wasn’t going to present himself as a highly visible target in Kabul any more than his successors would after the U.S. led occupation. They too would pass by with all possible dispatch, as did the Russians who would also get caught by the short hairs.

Rather than procuring the inside-out fleece known in the west as the Afghan coat, much prized by hippies at the time, I got fitted out with and toyed with the idea of buying a leopard skin coat. However I baulked at the final decision when I thought better of its future restrictiveness. I’d never be able to pull off the ‘cool’ of Jimmy Hendrix-only bell bottoms.

Thank goodness I didn’t buy it. One coat with it’s soft and beautifully marked fur is made from up to seven members of this magnificent endangered cat. I didn’t know that at the time.

In what is officially named Chicken Street in Kabul, the freak area, I dropped into a chye shop. It was places like this where travellers swapped road stories and snippets of information, got the latest news about border situations, visas, rip-offs, and good and bad hotels. A message board allowed travellers to leave notes for anyone and everyone they know.

Through it I met up with Max and Wolf, a Swiss and German, who were driving a Holden, still a wholly made Australian made car, to Europe. When they told me they had space available, I decided to throw my lot in with these overlanders and share expenses for the trip.

Keen on making a beeline to Europe, here I was retracing the Silk Road in style crossing swordlike mountains, high plateaus and deserts, whirlwinds gusting from the car back to the horizon. Looking at these isolated and barren landscapes, its hard to believe why any invading army would want to come charging in. These were the same hills and passes from which local foot soldiers attacked foreign troops. But this is where the British, to the sound of bagpipes, planted their nation’s flags in their unwinnable wars.

The highways were up to date, built half by the Russians, half by the Americans, having been played off each other by the local government. We encountered pastoral nomads on camels, materialising out of nothing, in the middle of nowhere, moving around the country with their herds as the seasons changed. Sometimes we saw their low black tents from the road.

Turbaned traders came out of nowhere tending iceboxes full of Coca-Cola which they sold to thirsty travellers. Overtaking peasants on donkeys we drove past mud houses in small self ruled villages, no women to be seen on the streets. Cut off from the capital, these communities posed no threat to the outside world.

We drove past bustling bazaars, minarets, trucks with their cabins heavily decorated, body panels painted with colourful scenes. and decrepit, fried out kombi vans often with peace symbols and psychedelia-polka dots, purple paisley and daisies- daubed on the side. Yeah, Baby! Feeling groovy?

The code of the road insisted that motorists assist any fellow drivers whose vehicles have broken down. In one village we stopped to help some women whose car had overheated and whose radiator was spewing out steam. While Max was cooling it down, a local stood on a balcony shaking a carpet. Max shouted up to him, ‘You’re having trouble with yours too, my friend? Won’t it start?’

Afghanistan was, if not united, at peace and that’s what all the visitors wanted. From the wild but welcoming state of anarchy there we moved on to a more restrictive, orderly society.

The Peacock Monarchy.

Onto the Iran border, where they were very heavy on drugs. A special exhibition inside the border compound showed the many ways people have tried and failed to smuggle drugs in. Max imagined the life of the drug enforcement officer we saw leading a sniffer dog: ‘I feel sorry for him. Imagine what he has to go through every day, taking drugs. And all those strip and cavity searches. All those pants around ankles, scrotum lifting, butt spreading and his torchlight illuminating anal sphincters. He must come home bushed after his day at the orifice’.

‘These invasive inspections, rough enforcement and language difficulties can lead to intense stress and anger. Officers affected can develop problems managing their emotions and impulses. These procedures can lead to a specific occupational illness.’

‘What is that?’

‘Borderline personality disorder.’

Wolf advised us not to be frivolous with our answers. When one headbanded New Age traveller wearing a jellaba and playing a flute was crossing the border, the customs officers asked if he had any drugs in his tie-died shoulder bag. He said, ‘Well, what do you need?’

It didn’t help him when he asked the probing orificer, ‘Does your wife know you enjoy this?’

It didn’t help him when he asked him, ‘What’s the first thing you do when you go home— throw up?’

What people like him got was another hippy, hippy shakedown.

What he got was being tripped over rather than tripping out. What he got was not so much turning on or tuning in but dropping out.[

As feared, a row of backpackers anxiously awaited inspection. They were on the edge of their seats.

A selection of miserable mugshots underlined the message.

Elsewhere shots of the Shah and his wife, the Jackie O of the East, were everywhere, ‘Big Brother’ style. Although I had my visa in order, the border guards slugged me with an extra transit .’It’s an old custom’s custom’, Max explained. ‘You’ve just got to grin and bear it.’

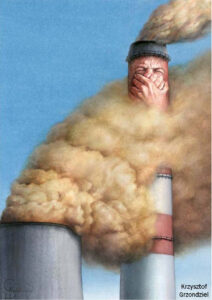

Once we were waved through, on the move, parched soil, shrivelling rivers and bare trees told us that Iran which had given the world peaches was in the throes of a major drought. Springs had dried up, seeds withered, crops burned in the fields. Although through doorways we glimpsed women whose faces and figures were hidden by the chador veil, this appeared a much more modern country than the ones I had left behind– if one judged it by the level of sealed roads, city lights, number of cars and other consumer goods and modern buildings.

No flying carpets nor snake charmers in sight, the capital at least seemed so modern as against those I had seen so far on this trip, with a smattering of department stores, reasonably orderly roads and cinemas showing Hollywood films. Women in the fast set went unveiled and dressed in high fashion with tight skirts, letting their hair flow and get tussled. At night we strolled along Lalezar Street, filled with cabarets, night clubs, bars, theatres, packed until morning. ‘Wow’, I said as this Cadillac convertible preceded and followed by a motorised police detachment drove along, the well tailored driver sporting a pair of RayBans.

’Maybe the King’s in town,’ I said. thinking of Elvis. As it drew closer I could see it was, but not the one from Graceland. Cruising along the boulevard was the equally capriciously extravagant, homegrown swarthy eyebrowed, full nosed monarch born into the role, also very partial to luxury American-made cars. I had seen him in a newsreel some years earlier riding in one through the streets of Brussels on his official visit.

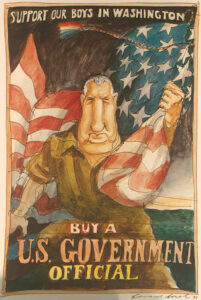

Back in the hotel we were staying in, its reception desk bearing brass busts of the Shah and his infamously fabulous wife, a group of American personnel were busily binging in the lounge. These technical and military officials were there to train the local oil industry technicians force‐feed the West’s most sophisticated military technology quickly to the Shah’s undertrained army. Their table littered with buckets of ice and bottles of Johnnie Walker, they caroused and guzzled grog as if it were going out of fashion. Their tongues loosened, they bellyached about the locals like any western expatriates in any developing country. One complained, ‘They’re unpunctual, inefficient, transparently childish, so fast and loose as to be useless to man and beast, as slippery as eels. We face an uphill battle with them. They have to be protected against themselves. If they would only understand what we’re trying to do for them. Nobody knows what it is to try to get these people to work!’

‘‘How can you talk about the citizens of your allies like that. After all they’re human beings.’

‘Only just. They’ve never learned the meaning of trust. They’re unnecessarily suspicious of foreigners. Yet they can’t run their infrastructure without us. Is this the thanks we get after all we’ve done for them?

‘What have you done for them?’ I asked, ‘installed a monarchy to subdue Iran’s Left and secure American access to the country’s oil.’

‘We saved them from becoming yet another domino to fall to the Soviet camp.

I would never trust forces that include the Communist Party as partners. I wouldn’t trust their fellow travellers further than I can throw them.’

‘Well we know where your allies threw them in Indonesia , don’t we.’

‘They have to be dealt with firmly. The natives were very restless before the Shah restored order, ruling more firmly.’

‘It was your Company’s planners who stirred up considerable unrest in Iran, giving Iranians the supposed clear choice between instability and enabling the Peacock Throne.

The move to oust the prime minister only gained substantial popular support this underhand way.’

‘They should thank us for boosting whatever support we have given, especially in the area of health. The peasants are full of disease, you know. Thanks to our aid the Shah’s health corps is eradicating malaria in the countryside. The peasants won’t be grateful of course but the least we can do for them is to help them combat it.’

‘Don’t you think these diseases have got anything to do with the shocking poverty in this oil rich country.’

‘That’s a reach. Most of them, even the poorest looking peasants have some silver or gold jewellery and currency stashed away somewhere. It’s their inertia and superstitions that keeps them sick. They want to stay in the age of the donkey.’

‘Maybe they want to move forward from a monarchy, especially a dictatorial one, to one like the one they voted for in 1952.’

‘Listen, the Pahlavi family come from good blood, from a good tribe. They get things done. Give the Shah credit for the reforms he has carried out. People have learned to read from his literacy corps and received government-subsidised meals and textbooks. He has modernised Iran’s rail infrastructure. He has taken its natural resources back from foreign interests. All in all, the Shah is resolved to transform his country into a second America in a generation. He’s dragging his country into the 20th Century.’

‘With some kicking and screaming so it appears. These improvements in people’s lives are to be welcomed. However once you embark on a program of reforms, you’ve got to provide them for everyone who needs to benefit. Foremost among these is freedom of political expression and association. It would be a big mistake for him to hold back from further reforms until it’s too late. Sometimes it is more dangerous to stop doing a dangerous thing than it is to continue doing it. He who rides a tiger is afraid to dismount.’

‘Life has improved substantially for the middle class during his rule. The White Revolution has led to the growth of an affluent, educated city society’

‘Perhaps life isn’t great for everyone. The economic changes he’s achieved have led to rapid migration from rural areas to cities. He has increased the income gap between rich and poor. On top of this there’s a lot of bitterness regarding the nation’s autonomy. The knowledge by many that Anglo American operations took away their “right to self-determination” can lead to long-term animosity toward them, particularly to your country. This anti-Western resentment could incubate in fundamentalist fringes over the coming years. Too close an identification with Western culture could stir in them a zealous Islamic awakening. Although the two countries are very different in most ways – Iran has a much greater level of industry and a sizeable working class – we know how this tension between the old and new plays out in Saudi Arabia.’

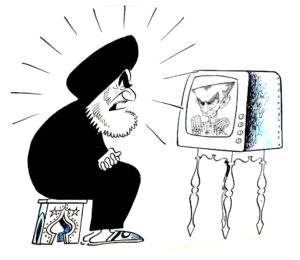

‘Nothing that a good stiff drink wouldn’t relieve’, said one of the Americans. ‘These mad mullahs need to lighten up. Not so long back theological students led by clerics agitated against a scheduled opening of liquor stores. The Shah had to send in his paratroopers when the locals started going bananas.’

In fact a good number of the Iranian population would have been displeased at the thought of these visitors to their country swilling away into the early hours of the morning. There were those put out by the presence of many Americans in their country, those many Iranians saw as having taken the place of the British. If this imbibing had led to any problems they would have wanted to penalise them. Yet any misdemeanours these expats might become involved in would have been overlooked. They were indemnified against prosecution.

Near the grand bazaar in Tehran is a colourful mural depicting symbols of Iranian nationalism including a dignified soldier, a machine-gun, and crossed Iranian flags.

Noticing my interest in the gun a young man introduced himself as Khalil, a post-graduate student of English at Tehran University.

‘American?’he asked me.

‘Not guilty. I come from a land down under.’

‘ Ah, you must be Australian. Some call it the 51st state but I won’t hold it against you.’

’Khalil pointed out to me, ‘That’s a Maxim. Quite fitting wouldn’t you say. This weapon most associated with the British imperial conquest, is thanks to Colt, it’s American makers, now a favourite weapon of our military.

Geopolitically it’s to empower Iran as a military power charged with preserving the balance in the Persian Gulf region. Domestically it’s to empower the security apparatus to ruthlessly dealt with all forms of political opposition. It’s favoured maxim when it comes to dealing with students and workers is ‘Shoot first, ask questions after.’

‘No warning shots?’

‘In some countries the police shoot in the air — in Iran they shoot straight ahead, that’s a warning for the next guy.”

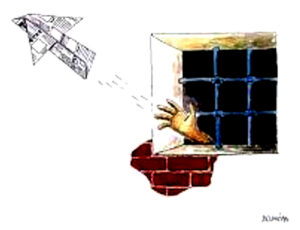

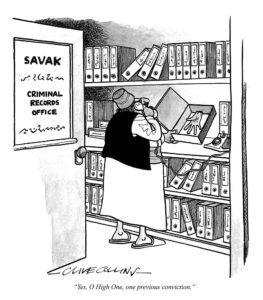

‘You don’t want to end up like all the political prisoners in the hands of the SAVAK secret police.

Once you’re in their custody it’s hard to get word out about it.

They’re infamous for their torture,’ said Khalil.

One of my friends had his facial hair violently and humiliatingly ripped off . I asked him, ‘What happened to your moustache?’

‘It was confiscated,’ he answered. ‘It will probably be sent to Langley for analysis.

‘They will look for any secret stache, ’I said, placing my index finger across my upper lip, ‘I’ve heard the screams of prisoners at SAVAK H.Q. can be heard throughout the night.’