In 1971 I took a break from London to live in the divided city. Only this time, unlike Belfast, the division was official. This was the sundered, storied city of Berlin.

Because of the historical images I had of this strategic centre – goose-stepping legions parading down Unter den Linden, daring B-17 raids giving them a taste of their own medicine, and then the Russians bagging the city to bring the European war to a triumphant finish, it had always seemed mythic.

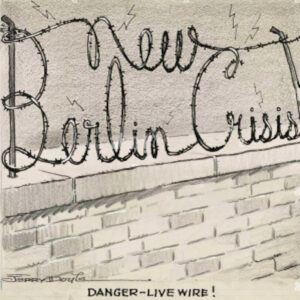

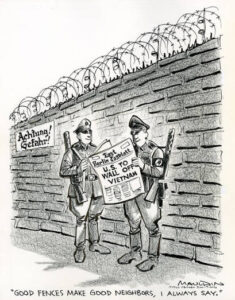

Then there was in my own lifetime the Berlin airlift crisis followed by the crisis following construction of the Wall.

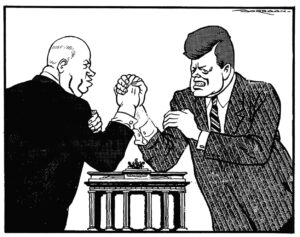

This engendered a a global atmosphere of danger as the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. wrestled for control of Berlin.

The tension would lead soon enough to building up that far off in the Caribbean- the Cuban Missile Crisis .

In the shadow of the squat concrete barrier up against which the tectonic plates of the nuclear superpowers now rubbed, I felt I would have my finger on the pulse.

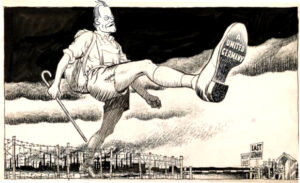

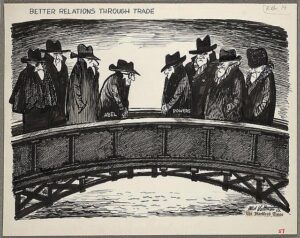

Relations between the two German states were always an indicator of the relationship between the two greater opponents – N.A.T.O. and the Soviets, determined that Germany could never launch a ‘revanchist’ third war of aggression on them. The Ostpolitik of F. R. G. Chancellor Brandt, including it’s dismantling of inter-German tariffs, accompanied the détente between the superpowers.

Previously such opening of relations was rejected by the F. R. G. leadership refusing to recognize its opponent. This was borne out in January 1964, when Walter Ulbricht, G. D. R. leader, dropped a line to the Federal Chancellor Ludwig Erhard, proposing that the Democratic Republic and the Federal Republic should conclude a treaty swearing off nuclear weapons. He said such a treaty was necessary because “prevention of a nuclear war has become a vital matter for the German nation. No German Government can say how many people will survive such a holocaust. Nuclear war would represent a direct threat to the physical existence of the German nation.”

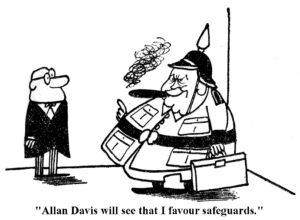

The Chancellor flatly rejected the proposal for safeguards , the same I had put to him. Ulbricht’s letter was returned unopened. Not so my own . I got no treaty but some recognition from this veteran of World War 1.

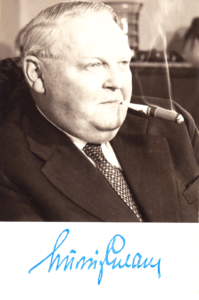

I received a portrait of the portly besuited Chancellor embodying that burgerlich quality associated with his consumer oriented policies.

Puffing on a cigar with the addition of a filtering safeguard. Maybe Ulbricht needed to sweeten his opposite number’s pot with some Havanas.

LBJ had tried to sweeten it by getting German support in Vietnam. Erhard had to reject his advances likewise.

West Berlin, a clear anomaly, this island of capitalism locked 100 miles inside Soviet-controlled East Germany, provided an ideal vantage point for making sorties into the East. I was intensely interested to see for myself the reality of spartan daily life on ‘the other side’, under the hardline Communist government which had abolished the power of capital and outlawed private ownership of the means of production – land, real estate, machines.

Like the oppressed minorities of Europe, including the ancestors of Heinz Jacobius, who filled the city some hundred years earlier and were instrumental in creating the city as it now exists, I was offered material incentives and freedom of movement in return for residency. There was work to be had. My first job was in the Hilton Hotel where I worked my way up from the bottom to the top. The classic uberkapitalistisch success story? Aw shucks. I started by cleaning the kitchen on the ground floor and graduated to cleaning the kitchen in the penthouse restaurant at the summit.

The hotel workers came from all corners of the globe. On the ground floor we were supervised with Prussian overseeing, glasses inspected to be gleaming clean, toilet cubicles rattled to rouse any sleepy hands who’d sloped off: ‘There’s no time to lean’, called the straw boss, Herr Mann. ‘You’re paid here to clean, not to twiddle your thumbs.’

‘Where would you be without me?’ asked one leaner.

‘With another new kitchen hand.’

One of the hands was extremely punctual. For years he had showed up on time. Seven A.M. on the dot and there he was. Then one morning he walked in at eight, big lump on his head, bloody nose and dazed appearance.

‘What happened to you?’ asked Herr Mann.

‘I fell down a whole flight of stairs at the U-Bahn station and almost got killed.’

‘This took an hour?!’

Herr Mann had an unforgettably sneering visage. It was always contorted in a manner that showed scorn or contempt. What is called in German a Backpfeifengesicht , a ‘face in need of a slap’. This ball breaker never called anyone by their first name. He scowled as he spelled this out to a new hand: ‘It breeds familiarity and that leads to a breakdown in authority. I refer to my employees by their last name only: Schmidt, Jones, Loren. That’s all. I am to be referred to only as Herr Mann. Now that we got that straight, what is your last name?’

The new guy, another Aussie, sighed, ‘Darling. My name is Steve Darling.’

‘Okay Steve, the next thing I want to tell you is… ’

We were rushed off our feet and it was with some relief that I got sent to the top. On the graveyard shift this offered a spectacular view with a galaxy of neon rainbows burning below us, rivers of headlights, a million blazing autos raising a roar, and pork fillet and delikat essen as unofficial gustatory rewards for our travails. Living high on the hog?

‘You might like to try out for a job here as a chef,’ one of my fellow workers said impressed by my culinary finesse.

’I’d rather be a cook,’ I replied.

‘So what’s the difference?’

‘The difference between a chef and a cook is the difference between a wife and a prostitute. Cooks prepare meals for people they know and love. Chefs do it anonymously for anyone who’s got the price.’

Our midnight banqueting came to an end when one of my colleagues took the lift to the ground floor. Our supervisor joined the lift, caught him gorging himself with cake and told him off: ‘You’re consuming hotel property, not the meal allocated you. You must control your appetites and show discipline. This is wrong on so many levels.’

After my shift I would return to the gastarbeiter hostel I was billeted in, in Kreuzberg, in Trizonia, the territory occupied by the capitalist big powers. Travelling on the U-Bahn to and from work I studied commuters from my father’s generation and wondered what their role had been in the war.

Kreuzberg was effectively an enclave within an enclave, being almost entirely surrounded by the highly guarded Wall. Moreover, politically and culturally it was known for its numerous Turkish immigrants. It was the largest Turkish city outside of Turkey. Kreuzberg was also known as a seat of dissidence. Thousands of pacifists had come from West Germany to avoid compulsory military service and were drawn to this cosmopolitan zone of tolerance and nightlife.

Others came to study attracted by generous incentives from authorities desirous of offsetting the aging demographic. I struck up a friendship with Ruediger Abel, a final year medical student from Kiel. Ruediger was learning a great deal about complications of the heart. He had fallen in love with another student from the medical faculty. The problem was she was in the East. ‘You can understand their cruel logic, circumstances not of their choosing’ he said, referring to the DDR’s unwillingness to allow her to join him. ‘They’ve had to plug the brain drain. They’ve had to stem the haemorrhaging of the professional manpower they’ve invested so much in to the West. Let me tell you a little joke. Have you heard about the Dresden String Quartet? ‘It’s the Dresden Orchestra back from it’s tour in the West.’

‘It’s a joke but one with a serious side.’

‘That’s for sure. Those leaving earn substantially higher wages in the West, not only because it is richer but because it’s a more unequal society, with much higher pay differentials between employees according to their skill levels. I have to use every argument in the book to get an exemption.’

In The Zone.

I was taken on as an employee of the British garrison forces based there. My role came under the heading of ‘labourer’. Their role was to enforce the military division, not merely of Germany, but of the European continent, complementing the political and economic cleavage. For example until the early 1960s the ‘Hallstein Doctrine’ decreed any state that recognised the DDR did so on pain of a full trade, diplomatic and cultural embargo from the West Germans . It was a key part of the Western Cold War project, the eventually successful aim of which was to isolate, weaken and destroy the Soviet Union and the Communist movement.

My main work involved keeping things spick and span.

The Berlin Brigade headquarters occupied the former Reich Academy for Physical Exercise (Reichsakadamie fur Leibesubungen) next to the Olympic Stadium. Today, I am led to believe, it’s the Sport Museum. The head of the Australian Military Mission had his office in this building and was of assistance to me in getting this work and with my documentation. Ralph Harry was Australia’s ambassador to the Federal Republic and doubled as the head of the Mission in Berlin.

I dropped into his office frequently as it was located in the main building of the military complex. I was able there to catch up on newspapers and magazines from back home. Mr. Harry expedited the renewal of my passport. An evangelical Christian, he expressed a belief in the banishment of all forms of war, poverty and oppression.

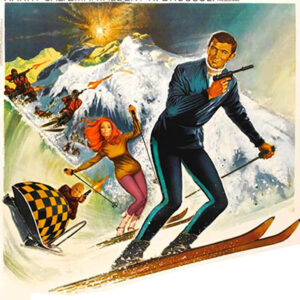

I followed the exploits of George Lazenby in the collection of Women Weekly magazines kept at the Mission and relayed them to the Mr. Harry.

‘Did you see “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”?’

‘I enjoyed it. It features emotional depth, solid fighting action and a smart script. It’s a faithful screen adaptations of Ian Fleming’s novel, dispensing with the gadgets and gizmos. However, it more than makes up for it with its in-jokes, glorious alpine locations and stunning ski chases.

With his attitude, swagger, and stature, Lazenby is believable as a deadly killer.’

‘Do you have a few moments to talk about it?’

‘We have all the time in the world.’

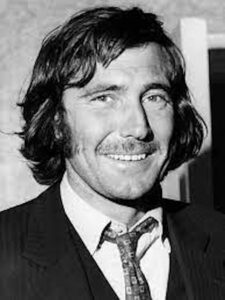

‘George wanted to put his stamp on the character, I said. ‘007 changed greatly since he was on it, he was different.’

‘Was he ever. He was the rebel Bond with a more human, darker and brutal edge. He went to one knee during the iconic opening title sequence, breaking the fourth wall – ‘this never happened to ‘the other feller’. And not just that, he drank beer not martinis.’

‘The boy from Queanbeyan, plucked out of obscurity, has now grown a beard and let his hair go long.

He says: “Peace – that’s the message now. Bond is a brute. I’ve already put him behind me. I will never play him again.”’

‘The other feller no sooner said that than he accepted the role again. Connery appears to be the distance runner whereas George was the sprinter. It’s wise never to say never sometimes.’

‘Gorgeous George has obviously been seduced by the counterculture movement with its emphasis on male sensitivity and gender equality.

‘On Her Majesty’s Secret Service’ is a Bond film with a female character that isn’t a cartoon. Bond falls in honest-to-goodness love.’

‘He showed his feelings.’

‘He wanted to make Bond more human and flawed When he did the scene where he cradled his dearly departed wife, he had tears running down his face, “The director said ‘cut! James Bond doesn’t cry, cut out the tears’. George sees things like love and marriage as things that people can relate to in life. He became convinced that the square-jawed, clean-cut Bond was an anachronism who wouldn’t survive in the age of Woodstock and ‘Easy Rider’. He became convinced Bond’s shoot-’em-up antics are seen as culturally irrelevant in this era’s peace, love and flower power uprising. His character doesn’t harmonise with this increasingly widespread hippy mentality. George thinks action heroes such as the stereotyped Bond will soon be seen as outdated relics, outdated, unloved and part of the establishment. With Bond’s short hair and tight pants, George thinks he looks like a cop.’

‘He’s obviously been influenced by Germaine Greer. He supports and cheers on the female emancipation movement.’

‘Let me read this quote of his: “I think women are superior beings to men because they have always been against war,”

‘He’s got a good point there. It goes back to Aristophanes. His character Lysistrata persuaded the women of the warring cities to deny all the men of the land any sex.’

‘It was the only thing they truly and deeply desired.’

‘George believes that war and violence are unjustifiable.’

‘He’s become a serious pacifist. Listen to what he says: “No country will ever convince me that I should go and kill someone in order to save it. If anyone told me today there was an advancing army just outside Botany Bay, I wouldn’t want to pick up a gun and fire away at it. I’d be keener to swim out and have a discussion about it.”

‘This ladies-man might just stop to chat up a Grey Nurse on the way.’

‘It might be the same one that raced Harold Holt off. Look I’m entirely in agreement with George. I’d like to be on the job like him. He feels like me, he’s in harmony with the Zeitgeist. Let me quote again: “I believe that there is a true revolution going on in the youth of today which is far more than just a fad or a passing fashion. The kids are beginning to learn that the world’s economy is dependent on the arms race, and they don’t like it. They feel the people going on and on making guns could be building new irrigation schemes to make the deserts productive, or making agricultural equipment to help feed all the hungry. People would be far happier employed this way than they are in wars and they would be saving lives instead of taking them.”’

‘I’m afraid that in the real world we have to always prepare for the possibility of going to war. War, while terrible is not always the worst option. MI6 on which the Bond character’s employer is based is well versed in the theory of just war as developed by St. Augustine. The purpose of the doctrine is to ensure war is morally justifiable through a series of criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. If Lazenby were working for the real British Secret Intelligence Service, that pacifist message wouldn’t get him much pull.’

‘True, but having long hair and bell bottoms enables him to pull more women. He feels getting laid in a suit is more difficult. George has matured in his thinking and is promoting our interests through a positive image of us. The film producers made him feel like he was mindless. They wouldn’t let him be himself to the extent he wanted. He felt hemmed in by the traditions and rules associated with the cliquey film industry. The word got out this out-of-nowhere was difficult with the other performers and technicians on set, that he just couldn’t deal with success. He feels the industry has boycotted him from getting further roles.’

‘He has brought on this cultural embargo himself. He made it hard for himself coming across as too arrogant for his own good.’

‘Now this ladies-man is free to cash in on all those pleasures of sex and drugs and rock’n’roll. The pill being on script has made the first possible.’

‘I’m rather uncomfortable with all that promiscuity, whether onscreen or off. I’m guided by St Augustine who said, ‘man’s wickedness is now of such proportions that no one is considered a man unless he is overcome by lechery, while one who overcomes lechery and stays chaste is considered unmanly.’ Are today’s young pleasure seekers so different to those of Augustine’s day?

‘Well, first off, let’s remember the times we’re living in. Augustine was referring to extra-marital relations whereas most of today’s hedonists ready to mingle are single. Second, the way Lazenby’s lace-ruffed Bond exists sexually is markedly distinct from Connery’s, and I think that’s worth underlining. Connery’s Bond is aggressive; he literally strongarms women into trysts. Meanwhile, Lazenby comes across as a guy who enjoys sex for the sex rather than as a means to dominate other people. It’s a kind of pleasure seeking that feels self-assured and secure, and that’s a hell of a lot more likable than being pressured into it.’

‘What’s Lazenby up to now?’

‘He’s hoping his ideas will be better received outside of the James Bond camp. He’s working on an anti-war film called ‘Universal Soldier’. Germaine Greer’s in it. He describes it as ‘anti-guns and anti-Bond’. He said the film was “the story of what’s happened to me. A lot of my friends are into yoga and I went to India to find out what it’s all about.” He says they taught him: ‘There’s another way if you don’t like this one’, and that the intuitive self should take over from the conditioned self.’

‘They sound like a bunch of trendy posers to me.’

‘ George is genuine about this. You don’t have to be anybody’, he says. ‘If the President of the US invites you to dinner tomorrow night it shouldn’t mean anything special because you are a god unto yourself.’ He adds that ‘If anyone had told me about yogis six years ago, I’d probably have chopped him in the mouth.’ Why do you think people are so interested in spies and the secrecy that surrounds them, Mr. Harry?’

‘Fantasy spies fascinate us especially when they are pleasing on the eye. Real spies are pretty boring and anonymous, but I guess are a necessary evil.’

‘Do you think the Bondian world as conveyed on cinema will continue to be developed?’

‘Yes, and the core of the Bondian world will remain the same: that obsession with sex and violence, hyper-masculinity, simplistic nationalism and addiction to conspicuous consumption. People find it an entertaining escape.’

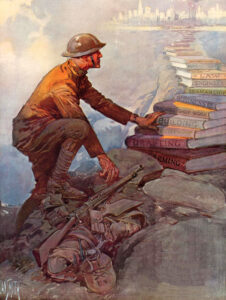

Another time I said to the Mission Head, ‘Mr. Harry, I see people everywhere in the DDR reading. At bus stops, in trains, in cafes and elsewhere. Reading seems to be considered a highly valued practice. Yet it’s said that there is a cultural embargo in the DDR. Is this your opinion?’

‘Reading is considered very important for the population generally, working class and all the way up – but only the right books.’

‘I recall having my rucksack searched for banned publications after I got back on Australian soil from South East Asia. The customs officials could have taken out anything they considered suspect.’

‘That was for different reasons. Our censorship targets obscenity. It’s to protect those whose minds are open to immoral influences.’

‘So what’s the difference between art and obscenity.’

‘Some would say it’s a government grant. Let me say this. Literature and art lift the mind to the heavens. Smut tethers it to the ground.’

‘And what’s the difference between what is erotic and what is obscene, I ask you?’

‘It’s the difference between using a feather and using a chicken.’

‘So who decides what is allowed? Surely beauty is in the behind of the beholder.’

‘It’s decided by those who are on guard against that which corrupts, depraves, emphasises violence and brings into contempt God and Jesus Christ.’

‘The standards they are imposing are out of line with what Australians hold to these days. East Germans don’t seem any better off. How much freedom of thought do you think citizens of the DDR have?’

‘East Germans have little freedom of choice in what they read and watch. Basically, every book that is printed in East Germany has to have permission to be printed, otherwise it won’t get printed. All printing presses in the country are kept away from public access. Even basic necessities like printable paper are strictly limited and under state control. Interestingly there are some Australian writers who are published there.’

‘Who would they be?’

‘War correspondent Wilfred Burchett writes some political work that the East German regime want to have in print, partly because it supports the point it is making, partly because it comes from someone who lives in the West rather than in the Soviet bloc.’

‘His special status with the Hanoi government certainly excited controversy, didn’t it?’

‘Not just in Australia but among our allies in Saigon. This became apparent to me in my last posting.’

One ARVN officer said to me, ‘Mr. Ambassador, how can you allow this friend of our enemies to send such favourable reports of them. Why doesn’t your government take action against him?’

I told him, ‘General, it has. Our government refused to renew the passport of this agent of influence. Against the wishes of many Christians it denied him entry to attend his father’s funeral.’

‘That’s nothing. While you are doing that the Communists in Hanoi are taking their hero out on the town. Why don’t you take him outside the town? Why don’t you just take him out?’

‘Like Big Minh and the CIA did to President Diem,’ I said.

‘I can neither confirm that nor deny it. As for the General, I told him, “We don’t operate like that in a democratic society. We have to tolerate a degree of opinions some consider subversive to our national interest.”’

‘Mr Ambassador, if you ask me, democracy is strictly for the birds.’

‘What about fiction writing in the German Democratic Republic?’ I asked Mr. Harry.

‘One of the people’s writerly choices in the East is an Australian Walter Kaufman.

‘His stories deal with Australian trade unionists and the disenfranchisement of the Aborigines. His novel ‘Voices in the Storm’ is based on his own past. Of a Polish Jewish background, his adoptive parents were sent to Auschwitz. He ended up interned in Australia during the war.’

‘He’s one of the Dunera Boys, isn’t he?’

Yes, one of those shipped off down under to be incarcerated during the war.’

‘Innocent men encircled by barbed wire and watchtowers.’

‘That nobody can deny.’

‘What else is popular reading?’

‘Another Australian novel breaking all the publication records in the East deals with an earlier colonial era imprisonment. For the Term of His Natural Life by Marcus Clarke.’

‘The convicts’ lives were extremely harsh weren’t they.’

‘The book depicts the hard life of the first convicts that arrived in Tasmania almost two hundred years ago.’

‘What do you put its popularity down to?’

‘One theory for the book’s success is the similarities East Germans feel with their situation a hundred years on. The convicts were cut off from the outside world and had to stick together against the authorities, just like Germans behind the Wall do today.’

‘So it’s about being trapped somewhere, about being locked up.’

‘That’s of course a fate that many East Germans share.’

‘Mr. Harry, do you see this painful division into two German states being permanent?’

‘Allan, as we speak circumstances in Europe and the wider world are undergoing a seismic shift. The Brandt government in the FRG is ‘normalising’ relations at a pace never before imagined.. Following the principles of his Ostpolitik, it is abandoning the ‘Hallstein Doctrine. The new Four Power Agreement – which regulates relations between the two parts of Berlin – should be followed next year by the signing of the Basic Treaty. ‘

‘How will this affect relations?’

‘ According to this the two German states will pledge to recognize and respect each other’s sovereignty. This will open the possibility for countries the world over – including Australia – to recognize the GDR without consequences for their relations with the FRG or other allies.

‘Maybe someday I can write a best seller based on my past including my stay in this enclave surrounded by barbed wire, armed guards and watchtowers as well as this historic thaw.’

‘As they say, Allan the truth is stranger than fiction. Just make sure I get a mention, though I must confess there’s been nothing strange about my life.’

It would be revealed only later that Mr. Harry was a former director of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.

Of course this international man of mystery couldn’t tell me that then. Embassies have their secrets; all operate in the space between what is said and what remains silent.

The existence of ASIS would remain a secret even within the Australian Government until the following year.

So too would the role it was playing role in preparing the CIA’s destabilisation of the Chilean government.

It focused it’s intelligence gathering efforts on what was happening there.

This operation hinged on cultivating a “coup climate” involving undermining the Chilean economy and the national polity by means of psychological operations until the country became ungovernable.

It would take half a century to uncover it’s role in the leadup to Pinochet’s murderous military putsch.

One that, unlike Hitler’s beer hall putsch, would be successful because of the Empire’s backing. Drawing the necessary connection led me toan important understanding. I concluded the Jakarta Method applied to Latin America meant the atrocity I had learned about a decade earlier had come full circle. It was a most vicious one.

Like my own, Mr. Harry’s mission in Berlin was to protect and promote what we interpreted as Australia’s vital interests.

They were, though in different ways, all about penetration.

His was to penetrate the inner circle of the Communist state.

Mine was to penetrate the outer circle of its women.

I was very open about this.

I said to Mr. Harry jokingly, ‘Could you declare inside my password, “Please ensure the safe passage of the bearer of this document. He is a citizen above suspicion.”’

‘I don’t need to, Allan. That goes without saying.’

As a condition of employment at the headquarters I had to declare that I had never been a member of any Communist Party. Big Brother kept a particularly watchful eye in this realm. I was working in a high security area. At the time the dragnet for the Baader Meinhof group was in full force so presumably everybody was being scrutinized with rubbber glove thoroughness. All-clear, I was deployed with the unit involved with liaison activities with the Russians at Potsdam.

‘Our role,’ explained the military liaison officer overseeing my work, ‘is to coordinate activities to protect units from collateral damage. We work to achieve mutual understanding and unity of effort among disparate groups. For incidence or disaster management, our liaison officers serve as the primary contact for agencies responding to the situation.’

The moderating of the confrontational policy of the opposing blocs was welcomed in the armed forces. ‘Better a wall than a war’, one of the commissioned straight-arrows confided to me.

‘It has actually helped us to breathe more easily, being much more fortified than what the Americans wanted to build in Vietnam.

.

It has brought greater economic stability to the G. D. R. While I wouldn’t want to live there, their per capita GDP has risen above that of the United Kingdom.’

‘What about the human cost? It has divided families, fathers from sons, mothers from daughters.

It has truncated the city’s existence, divorced people from one another. It has prevented the warmth of human contact between two halves of the city, between different kinds of people, the only thing that can save us. It has led to deaths.’

‘What about all the death and misery the Germans inflicted on the world? They bear most of the responsibility for the Wall. It has brought about a clearer, more stable demarcation line. It has helped prevent any further standoffs like we’ve had in the past with tanks confronting each other across no-man’s land .

It has helped to defuse this dispute that’s hung over us from the Second World War. A strong signal from Moscow that the Eastern Bloc is not planning a strategic intervention.’

‘Weren’t the signals clear enough before this?’

‘Nothing as clear cut as this one. The Wall has pulled up short troops with itchy trigger fingers getting stranded in the wrong places. If it hasn’t pulled up Germans who can’t read the signs properly, that’s their lookout. Now neither side in this standoff can wipe the floor with the other. It’s on all our heads to stop things going too far. It’s a tricky balancing act.’

‘That’s the way the mop flops.’

‘For sure. No one wants an all-out white hot nuclear conflict in the heart of Europe.’

‘Check’, I thought, ‘me especially’. A strike on this garrison meant I’d be selected as a volunteer, one of the cleaning commandos pulling extra duty. One of the hotshots lumbered with mopping up operations, clearing up the god almighty mess. A bit like jumping into someone’s grave.’

Providing there was no such strike, carrying water for the military was a good job as jobs went. I went happily about giving the place a good going-over. Sweeping, waxing and buffing the floors. You could see your face in them. Dusting surfaces, scrubbing, spraying and scouring, rubbing Brasso into metal, wiping lockers, leaving bathrooms antiseptic. Overlooking no cavity, no detail too small. Removing the human debris shed by the soldiers and mechanics. The flakes of skin, filaments and fibres, the nail clippings, the wisps of dead hair, the invisible armies of parasites, those minute specks of life that make their living by nibbling at us. With a whisk whisk here and a whisk whisk there and a dustpan for the cinders. With a rub rub here and a rub rub there I would polish up the windows.

‘Rub a dub dub, where is my tub?’ I once asked the German mechanics in the store room, while looking for my pail. I received the reply: ‘Hey Diddle Diddle! Right here in the middle!’

‘You’re like one of us when it comes to cleanliness’, one told me. ‘ A quick once-over with your broom and we’ve got an immaculate room.’

‘Let everyone sweep in front of his own door, and the whole world will be clean,’ I said, quoting from Johann Wolfgang Goethe. ‘I clean up our own mess here and keep my nose out of other people’s business.’

The officers complimented me on my thoroughness and white glove spotlessness. ‘The state in which our unit is left is the best possible test of the efficiency of regimental officers. It is on such matters that the reputation of a battalion and its commander rests,’ said one. ‘Our’s suffered following the performance of Major Mophead, your predecessor.’

One pernickety sergeant stressed the importance of having everything in the right place: ‘Maintenance of facilities and materiel is a vital part of logistics and the movement of troops. No detail is too small to be passed over. It’s the small apparently trivial ones that mustn’t be overlooked.’

I showed him the box I kept for collecting any loose metal spikes I collected from the grounds. ‘They’re better here than in tyres,’ I said, fastening another to the proverb, ‘For want of a nail, and for one unwanted, the kingdom was lost.’

Another officer told me: ‘Good going. You’ve outdone yourself again, Allan. Better than bog-standard. You never fail to satisfy. Your going-over hasn’t passed unnoticed. Our bathroom’s as clean as a whistle. With the magic of your broom, you can mesmerize a room. It makes us blink, to stop and touch. You and your broom accomplish so much.’

‘All part of the service. As I say back home, ‘My duties I never shirk. I’m your tax dollars at work.’

The unit brought fringe benefits – foodstuffs from East Germany which I helped deliver to the British troops. Unfortunately, being assigned only to the delivery end of the grocery detail meant I couldn’t qualify as a ‘Hero of Labour.’

I was able to procure cheap pork and sundry items from this same source. These perquisites were part of the modus vivendi arrived at by the various occupation forces. I got to chow down with the soldiers and non-commissioned officers and ate jolly well. They called their mess The ‘Cafard Café’. This was not the snack-bar facility provided in some messes, but rather with properly served meals.

‘We like to take food and drink in a congenial atmosphere,’ one sergeant explained to me. ‘One where stimulating, intelligent conversation, good cheer and sparkling repartee are the custom and routine. Here civility, good manners and good taste, a basic and lively consideration and respect for others encourage the healthy relationships so essential in a first-class fighting unit. However there are rules developed by the mess, ones which contribute so much to the sense of satisfaction of good fellowship and good dining which can never be broken.’

‘Could you give me an example of one?’ I asked.

‘The cardinal rule is that the cook always come up with good tasty food. Pity help the cook who fails to heed this.’

In the mess they discussed the military history of the surrounding region.One place in particular was that around the town of Halbe where a vital breakthrough by the Russians took place in April 1945.

‘This area of pine forests and lakes is one vast graveyard. You wouldn’t want be a gravedigger there. There’s still too much unexploded ordnance.’

‘Have you been there?’

We’ve just visited the cemetery next to the Baruth–Zossen road with our Russian counterparts. We paid honour to their fallen compatriots, part of the high losses exacted by both sides. We placed wreathes on graves.’

‘What was the significance of their ferocious offensive?’

‘This was the prelude to the Fall of Berlin.

‘The Kremlin’s standing orders were to surround the city and drive a stake through the black heart of the Reich.’

‘Correct. To isolate the ill-equipped and tired remnants of the German Ninth Army in the Spreewald ‘pocket’, southeast of here. Stalin’s directive was for it to be surrounded and delivered a death blow.

‘The terrain outside would have been unforgiving and slow to move through.’

‘The Soviet offensive launched on April 16, 1945 isolated the German Ninth Army and tens of thousands of refugees in the Spreewald “pocket”, southeast of Berlin. As I said Stalin ordered its encirclement and destruction and his subordinates, eager to win the race to the Reichstag, pushed the 9th Army into a tiny area east of the village of Halbe. To escape the pocket, the remnants of the 9th Army had to pass through Halbe, where barricades constructed by both sides formed formidable obstacles and the converging Soviet forces subjected the area to heavy artillery fire. In the slaughter the 9th Army suffered catastrophic losses compatible with any suffered in the Soviet Union. ‘The massacre was appalling, wounded were left untreated and screaming by the roadside.’

‘Many of these were just kids, weren’t they?’ I said, ‘Kindersoldaten given as offerings to the enemy by their fanatical leader, his own days numbered.’

‘Teenaged draftees fought alongside Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS veterans attempting to maintain military discipline amid the chaos and carnage of headlong retreat. Their army commanders strove desperately to extricate their decimated units, hoping to escape the Red Army and surrender to the Allies, seeking better POW treatment.’

‘Quite understandable considering their monstrous, maniacal, merciless, military machine had laid waste to Russia and killed so many.’

‘This battle was total war upon soldier and civilian alike. a great and terrible event.’

‘History looms large there. It’s just one generation since these battles took place. The wounds of the Second World War are still not healed.

Let’s hope that you never get drawn into such a horror.’

‘We are reminded of that possibility whenever we cross over the Glienicker Bridge into Potsdam. This is where Rudolph Abel and Gary Powers were exchanged to avert such a confrontation.

On the Dotted Line

I was curious why young British men still signed up. The losing American war against the Vietnamese suggested it might finally be getting harder to keep the natives down wherever. This ally’s habit of spreading collateral damage suggested one give their forces a wide berth.

One corporal gave me the following personal reasons: ‘In this situation I have power totally out of proportion to my age, experience, training and rank. I’m a man among men. Why would I want to go home, take off my uniform and be a nobody in a job where I have no independence and no power. Why would I want to be surrounded by people who have absolutely no interest in where I have been for the past two years or in what I have been doing. That’s if I got a job. I’d probably be pushed to the back of the queue for jobs, overtaken by those in civvy life. And, anyway, what job is there in civilian life to fulfil the expectations of a front-line swatty?

His sense of belonging in the army had been the only constant in his life and he had no family or relationships outside it.

‘What’s the first thing you’ll do when you return?’

‘I’ll be heading right for Hyde Park.’

‘Why Hyde Park? I thought ducks were out of season.’

‘Not the kind of birds I’m after. I’ve got some savings put aside to give them a great treat.’

‘What about German girls. How do you get on with them?’

‘Not too well. I’m afraid. I don’t speak German. Besides, I’m very much a wallflower to start with. I went to a Christian boy’s school.’

‘You’re a presentable man. You can pick it up and them too. I wouldn’t have thought you’d have trouble there.’

‘I don’t have the gift of the gab in English let alone in German. Never had it.’

‘That’s what makes you feel inadequate?’

‘More bored than anything else. It’s why I joined the army, to scare up adventure. Moreover I was able to learn a trade.’

‘That was a drastic choice. You can learn a trade if you don’t. And you can devote your time off to your lass.’

‘You can experience more of life in the army’.

‘You think you can become a more authentic person by fighting in a war? Why, given every other possible option, does a man choose the life of a paid killer?

‘Well, it was that or the priesthood.’

‘Jesus Christ didn’t think it‘s right to kill others according to the Good Book.’

‘You’re against joining up is what I’m sensing.’

‘Let’s put it this way: most men kill for fear of being killed, but some kill for joy, racism, duty or career. Some feel there’s something inherently psychopathic about someone who joins the army in peacetime. As far as they’re concerned, they join the army because they want to find out what it’s like to kill someone. I hardly think that’s an inclination that should be encouraged, do you? The Commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ does not have an asterisk beside it, referring you to the bottom of the page, with instances where it’s OK to kill.’

‘What about self-defence?’

‘It’s a tricky one, all right. Britain’s hardly being invaded, though, is it?

Who knows what goes on in the Communist mind?’

‘We knew what was going on in it when we were all fighting the Nazis. The legitimate enemy. Is it a different mind now? Do you have inclinations to kill?’

‘I have had very violent feelings I have to admit. It doesn’t mean I could be a wife beater or get out of control. I just feel angry towards people. And warfare being such a natural part of the human identity, I thought, well, if I join the Army those inclinations, as you call them, would be seen as a plus. On the application, they don’t come out and say that’s what they’re looking for. In the ads, they tell about seeing the world and all that shite. But I would assume wanting to kill someone would be like having a degree. It would outweigh my lack of qualifications.’

What no one at the garrison knew then was that amongst their numbers was someone who would go on to become one of the sickest murderers in British history. One of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders stationed there, he would murder men to have some body to sit next to. To have somebody at home to eat.

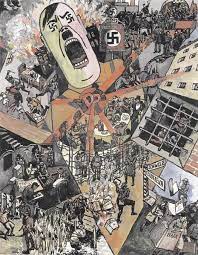

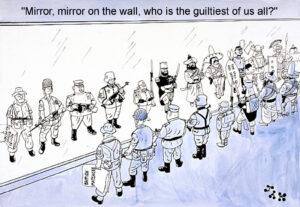

When my duties were over, I polished my German language and cleaned up my understanding of German history. Like most people I was fascinated by the big questions.

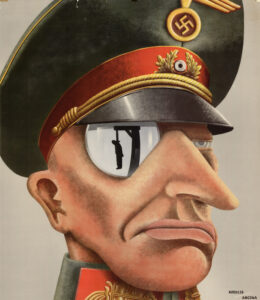

How a country of such rich culture could have descended to such depths of inhumanity as during the Third Reich.

How it could have brought such sorrow, starvation and death to Europe.

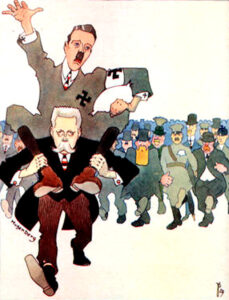

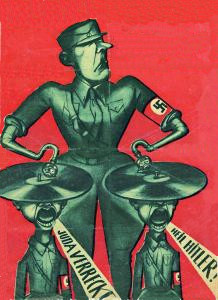

How a democratically elected government could have been pressured to accept an anti-democratic demagogue riding on its back.

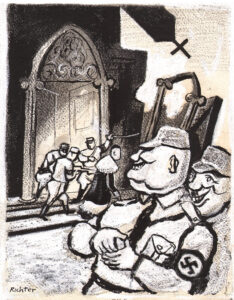

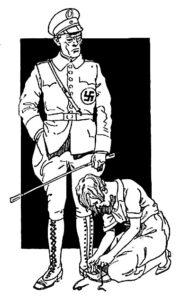

I was at a vantage point to explore imaginatively how the loathsome thugs and debased elements of society were able to get their stranglehold. Enabling them to perpetrate the most malignant, calculated, devastating crimes in history, liquidating with industrial efficiency the labour movement, slews of the liberal bourgeoisie and the core of European Jewry.

The past becomes more tangible when one experiences the environment in which it occurred.

This erstwhile athletic training ground for the sporting elite, still largely off limits to the public, offered a key to understanding this. It had been a dazzling showpiece for the regime designed to demonstrate the supposed physical superiority of the German people. It helped to blind people to the social and moral destruction it was perpetrating.

Making my way through the corridors, rooms, halls and grounds of this complex, moving materials and equipment as I went, sneaking snippets about its history, cleaning and gleaning, led to me becoming intimate with its layout and workings. Built to high standards with a simple functional décor, the main building didn’t need or receive much alteration when it passed into the hands of the victors. I got the feel of the previous occupancy.

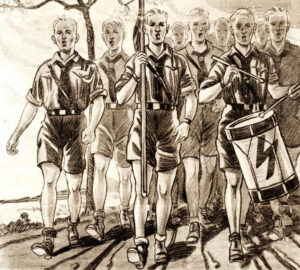

Redolent with the sweat and shouts of marching youths it evoked the valhallan ghosts of a generation devoured by the Nazi state.

For this promising young talent of the athletic world, the warrior attributes of courage, sense of duty and simplicity were deemed as vital as fitness, strength and stamina.For many of them it offered more than they could hope for, outdoor activities without class distinction. Their compulsory uniforms hid their social differences.

The grounds were adorned with statues of heroic figures. These represent the idealised qualities of physical perfection the Nazis wanted instilled in the youth and the power of the state. I could see them coming to life; shot putters, discus and javelin throwers. After burnishing them, whistling Wagnerian strains I moved on to pollarding the trees that dotted the grounds. In their earlier days their young limbs had become entwined with those of those budding leaders climbing hand over fist to the top.

Their activities imitated those of war. Agility at climbing trees, swinging from one to another and running zigzag between them was essential to gird the loins of the potential guerrilla fighter. As was jumping from the ledges I cleaned onto a large canvas held by other students on the ground. Some of the highest ledges were very narrow. I myself could never have jumped from them. Some people have no head for heights. Not me. I have none for widths.

These were a number of the rigorous, root and branch ‘Mutproben’ or courage tests designed not just for the track and field events, but for fighting for the the Fatherland and the Fuhrer. Through a combination of force and seduction he had built an exclusive relationship with the contestants’ generation. Too young to smoke or drink these teenagers became increasingly old enough officially for the front line. A competitive spirit was encouraged among them at every level. It was all about readiness for the war to come. They would need to sharpen their eye for detail.

With my own regular measured tread I walked around the tracks that had been followed by the boys. They had practised endless marching in columns round the grounds. Music at the front, drumming and trumpeting behind the flag, demonstrating to them that they were someone. Their step had become standardised like their thinking.

The crowd roars that went up from the adjoining Olympic Stadium took my mind back to those emanating from there when the great Jesse Owens swept the field with his virtuoso performances. His victory affirmed that individual excellence rather than race or national origin distinguishes one man from another. Nazi propaganda had depicted ethnic Africans as inferior.

If anything might have put a dent in the fiction of Aryan physical supremacy, this would have. But the Nazis were never ones to let truth get in the way of a good myth. None of the students or teachers would have dared draw attention to such triumph. Any sign of independent thought or criticism was eradicated by summary expulsion or dismissal proceeded by humiliation. All had to march in equal step, all had to submit to the regimental cast of mind.

While I was working around the gymnasia, the apparitions of athletes sweating it out in rigorous drills and of boxers locked in combat formed shadowy outlines. Boxing that had been made compulsory in the upper school to heighten boys’ aggressiveness here took pride of place. It was a gloves off approach in which the contenders were egged on to pummel each other to the edge of unconsciousness.They could hardly have been expected to show mercy and pity towards each other, on the canvas, if the aim of the exercise was to stifle expression of such ‘weaknesses’.

Dr Strangelove.

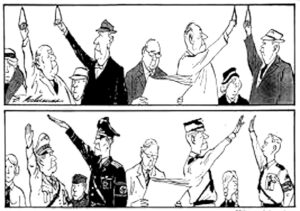

Some of the former classrooms still had the original blackboards on the walls. Armed with a piece of chalk and some pictures from magazines, I aimed to go over the top, assuming the persona of the manic twisted Nazi teacher Dr Merkwurdigliebe, whose name loosely translates into Dr. Strangelove. I based him on Peter Sellers ’ older disabled character in the film of the same name.

Seated in a wheelchair from the infirmary, my right hand clad in a menacing black glove, I feigned a severe case of alien hand syndrome, this arm shooting out in a Nazi salute when I got all shook up. In such moments as when I drooled over the joys of Nazism, I cried out “Wunderbar!”

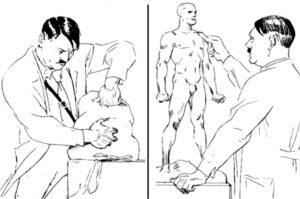

In this guise I expounded the central tenet of the National Socialist state to the ‘students’, played by any workers and soldiers who happened to be around. After introducing myself and greeting the class in a guttural Katzenjammer Kid accent, I proceeded to write a series of key words on the board. ‘Eugenics’. “Zis I explained clunkily, “is our guiding social philosophy. Wundebar! In it ve aim to recapture our primeval essence of blood and soil. Ve advocate the improvement of human hereditary traits through various forms of intervention. Vot kind of improvements do ve vant?’, I asked rhetorically. There was a pregnant pause as everyone waited for the answer. “Ze Aryan’, I came back churlishly, bunging it on, ‘Ve want to preserve und enhance ze purity of ze Herrenvolk. Our Fuhrer being the great artist he is wishes to sculpt ze values that he believes our youth embody – ideals of harmony, athletic vigour and beauty .

Vot ve vant most-fair skin, blond hair, blue eyes “uberalles”. Ein schturdy build for die frauen und broad hips. A strong, vell developed body for the men.

Schlender like Goering, tall like Himmler und blond like the Fuehrer. Mit kein defects. This is the vision of the Fuhrer,’ I declared holding up one of those rare photos of Hitler that got past the censors and past Merkwurdigliebe’s notice, showing this ogre wearing spectacles to correct his failing eyesight.

This was just part of the huge discrepancy, obvious to Blind Freddy, between the physique of the dictator and that of the muscular Nazi ideal. He was relatively short, brown haired and doughy featured. One of the great ironies of the leading Nazis was that none of them looked like the Aryan stereotype.

“Dr Goebbels vants it to be known that physical disability must be bred out!” I cried, holding up one of those rare photos of Goebbels that also slipped through, showing him limping along because of his club foot. This was the only distortion that Hitler, averse to those with physical deformity, would not welcome from this ruthless spin doctor.

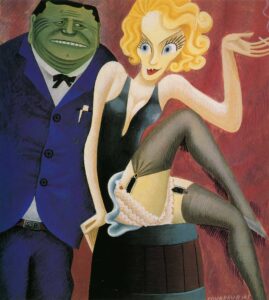

To demonstrate Aryan racial superiority, I used a plastic skull I bought from a party supplies shop and a measuring tape. I used these to show the specific ideal depth, height and width of the skull. I expounded on the ideal colour of the eyes and hair and the racial categories of Nazi ‘science’. ‘You are Type 2 Nordic, I would say,’ I said to one member of my class, 80 percent Nordic at least’. ‘This man is a sub-human’, I said showing the class a photo of Irving Berlin.

“Boys and girls, You vant to see Aryan purity, I’ll show you who I tink fits the bill. Zis is vot our Aryan Venus looks like” I held up a picture of Marlene Dietrich that blonde vision whose sensuality came with a cool languorous arrogance. It was presumably these latter attributes as well as her nice set of pins that had so enchanted Hitler and Goebbels. “A little bird has told me zat der Fuhrer vud like her to kom home from Amerika”.

The image of the down to earth ‘farm girl’ with braids was the one the regime wanted to promote.

As with everything this was different to the glamorous one their own wives and mistresses wanted for themselves. ‘La Dietrich” would have been expected to tone down her image as a ‘femme fatale’ and become more simply ‘fatale’.

The next word I wrote was ‘Lebensborn’. “I have recommended to the Fuhrer zat I be able to build up a group from you, zer strongest and most energetic of youth, to take part, when you are a little older, in the Lebensborn program under my supervision. Our aim vill be to breed many of the most racially valuable children for ze Fuhrer unt zer Fatherland. Ve haf a castle vere you vill be zer knights unt zer yung maidens”. I was alluding to the Nazis evoking the ethos of the medieval teutonic knights.

Swearing strict obedience to the Ordensmeister, the not so silent knights rode roughshod over the serfs and churls at the bottom of the social pile. And their own children.

“You will be selected according to how highly you score in terms of Aryan features and strength. Girls, you vill vurk hart making die kindereggs. Boys you vill rule der roost. You vill have two partners each. Wunderbar!”.

Becoming very animated at the thought of this scheme I broke into song with a Mel Brooks take on “Surf City’ written by Brian Wilson from the Beach Boys.

‘Two girls for every boy.

We’ve got a castle on the Rhine where the country is quite woody. Serf City here ve come.

You know it’s not very modern, it’s an oldie but a goodie. Serf City here ve come.

Well it’s more of a village than really a city. But it still gets us vere ve vanna go.

And ve’re going to Serf City cause its two to one you know ve’re going to Serf City, gonna have some fun.

You know ve’re going to Serf City gonna have some fun now, two girls for every boy.

You know the serfs do all the verk and we’re sitting pretty.

They’ll pour our drinks as I sing this ditty and when ve get to Serf City

I’ll be shootin’ some churl and checkin out the Party for an Aryan girl.

Und ve’re going to Serf City cause its two to one.

You know ve’re going to Serf City, gonna have some fun.

You know ve’re going to Serf City, cause its two to one.

You know ve’re going to Serf City, gonna have some fun now. Two girls for every boy.

You know zey never roll the streets up und zere’s alvays somezink goin on, Serf City, here ve come.

You know the boys are out street fightin’ cause we’ve got a Party growing, yeah, and there’s two swinging honeys for every guy, and all you you’ve got to do is just vink your eye.

My next item was ‘Racial Hygiene’. ‘Ve haf to remove those degenerates who are mentally or physically unfit. Their blood can gush out anywhere at any time and pollute and defile ours. The worst ones – the Jewish. While I spat out this word of contempt my right hand slowly rose, moved to the inner pocket of my jacket, and with considerable stealth took out my pistol with the intent of brandishing it in the direction of any imagined Jewish intruders. At the last minute my free hand seized the other holding the weapon and both grappled for its control. My free hand prevailed. After a moment I, the respectable scientist, realized I had gained the upper hand and was able to contain any further overt expression of this violent sub-conscious urge.

Regaining my composure, I warmed up again to my special talent as the Reich’s singing spinmeister. I filled the class in about how I would approve each applicant. “Jungvolk, zere is a German song vot is taking the world by sturm. Ven I hear it I think of young maidens like Marlene and their place in the Reich. I vood pass them mit dieser vords, “Of all the girls I’ve met, and I’ve met some. The moment I met you, it was awesome. And when you came in sight, dear, my fist grew tight. And the Old Order seemed New to me. You’re really swell I have to admit, you deserve expressions that really fit you. And so, I’ve racked my brain, hoping to explain all the things that you do to me. Bei mir bist du schon, please let me explain.

Bei mir bist du schon, mean that you’re grand.

Bei mir bist du schon, again I’ll explain.

It means you’re the fairest in the land.

I could say “sehr gut” sehr gut, even say Wundebar, our language tries to tell how grand you are.

I’ve tried to explain, beir mir bist due schon, so listen and say you understand.

While I was happily rapping away, one of my “students”, a workmate, and a performative plant for this occasion was unsuccessfully trying to catch my attention.

“Junge, Junge, was ist los, what’s up?” I asked him.

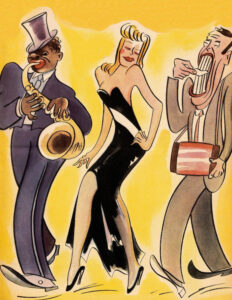

“Mein Doctor, I’ve been trying to tell you. Dietrich is a falling star. Haven’t you been reading? he said, handing me a copy of the Party’s magazine ‘Youth and Homeland’. Its banner headline trumpeted ‘Marlene Dietrich Betrays The Fatherland’. ‘She has turned her back on Germany and dances around with those obscene negroid jazz musicians so detrimental to Aryan musicality and their unhygenic, gum chewing followers.

They said her face is her fortune but now she’s lost it zis shiksa keeps company with those Jew moneymen of Hollywood ”, groaned the shill.

‘Not only that, “Bei Mir Bist de Schon turns out to be a Yiddish song. ’

Dumbfounded, hit between the eyes, I reeled under the shock of such news while my alien hand inched threateningly towards my throat. Fighting off this assault with all my might and main, I slumped into a chair, crestfallen, groaning “Mein Gott! Ist nuffink sacred?”

A Uniform Appearance.

Assigned the duty of removing certain items of clothing from the stores and taking them to be destroyed, I came upon some items of interest. One was an Air Raid Precautions coat. It had been worn in London by those first responders in charge of protecting civilians during and after aerial bombing.

They marshalled people to shelter during the blitz in London.

It was brought to Germany to keep some soldier warm at a time of shortages. This coat must have had some stories to tell.

I would have had one big one to tell if another Big One was dropped.

With its array of shiny silver buttons, it well may have prompted strangers to ask me for directions and assistance to the nearest bomb shelter.

Epitomising the strong supportive man and the elegant one at the same time, I offset its grandeur in the coming years by wearing it over more casual attire — jeans, cardigan and T-shirt — a look that suggested I came into possession of my outerwear not from being in a service but from, say, a vendor at a chic market.

My son Sean with his certain rakish elegance would later wear it to keep him warm on those occasional cold Sydney nights. Who wouldn’t mind being identified as marching in style’s infantry?

It did something for me back then in Berlin. It convinced me that with the right material I could make dramatic theatre to rival anything that had taken place here. It was a plain uniform which struck me as being similar to the type Hitler wore. This was the first prop I needed for my rendition of Fuhrer’s address to the Academy’s convocation. I was pastiching the style of Chaplin’s burlesque of the demonic tyrant in “The Great Dictator”.

In preparing it I paced up and down whatever room I was in, putting my ideas to rhetoric as composers set theirs to music. The feather duster in my hand served as a baton to punctuate the rhythm of my words. I tested words and phrases, muttering to myself, weighing them; striving to balance my thoughts, making sure the sound, rhythm and harmony were to my liking. Then I came out loudly with my choice and wrote it all down. At times I thought, ‘Scrub that and start again.’

Then it came time to rehearse. I practised it by reciting loudly. No opportunity to rehearse was overlooked, even while I was shovelling snow.

I had a lectern already in place in the assembly hall. In the front row was Australia’s ambassador to the Federal Republic. He was happy to accept my invitation to the speech on short notice. ‘I wouldn’t miss it for the world,’ he told me.

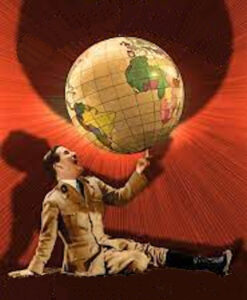

Knowing the speech backwards, I kept in mind the requirements of a good one. It had to be like a mini skirt; long enough to cover the subject and short enough to create interest. All I needed was a make up flag drizzled with red paint, a drum and a large globe of the world I borrowed from the Military Mission to captivate my standing room only audience with. Rather than the gibberish and gobbledygook that Charlie mastered in order to ridicule, I stayed with simple English. I aimed to convey Hitler’s ideas on education lacing the flowery and bombastic language that characterized his compelling oratory with as much iron, sturm and drang as I, beating back butterflies, could muster.

Slipping into the skin of the most sinister figure who had ever drew breath, with my studied technique I slowly, almost hesitatingly and solemnly mounted the rostrum from where I’m told he delivered his speech to the Academy.

Cue the rhythmic beating of a drum played by a fellow cleaner to accompany me. A hushed silence fell as I approached the lectern, clicked my heels together and, thinking on my feet, hamming it up, launched into my demagogic spiel. Ta da!

Heil, O doughty youth!

Athletes of the Third Reich

From our hills and lowlands,

Living guarantee of our future,

Champions of the world.

The shining destiny of our cherished Reich,

Stronghold of light,

whose honour and instrument I am,

commands me to guide you.

Let no one believe that I am

Other than the Fuhrer.

As I gaze upon you

I pride myself on your physique

Temple of the Aryan spirit.

Long slender limbs, rapid as a hare,

Tough as leather at which all will stare,

As hard as Krupp steel

From top to bottom

You embody our ancient heroic values

Brains unsullied by egghead Marxists

Moulded not in stuffy classrooms

But in gyms and open fields

Encased in thick skulls

To batter down unopened doors

And butt in when not asked

Versatile eyes

Unstrained from reading

That can home

In on distant prey

Yet see nothing,

no further than your nose. ’

Up to now I had been studiously restrained, waxing lyrical about the excellence of my subjects. Holding the audience in the palm of my hand, I proceeded to tear myself into the part and work myself up more into my characteristic rant and rave. Rising victorious over my falterings, my gesticulation becoming a pantomime, I shrieked hate, barking, baying and spraying bile on my enemies, pacing back and forwards to drive home the message.

‘A good nose for stinkers

For smelling out rats

Best kept to the grindstone

To crush them like gnats

The sharpest of ears

Kept close to the ground,

Turning deaf in a moment,

Mourn not that our men are dead,

Since more will die tomorrow.

If there’s sorrow around

Bite your lip when this happens

Cut it, there’s nothing wrong.

Keep a stiff upper lip

And you’ll always be strong

A tongue that is forked

To promise the world

And lash all our critics

When our flag is unfurled

Your bronze tinted skin

Treated to ample fresh air

For pasty faced Limeys

Is something quite rare,

A spine that is rigid

Ramrod and straight

Unbent from study,

Bound to our fate

A heart that is brutal

Unyielding and callous,

Throbs violent always

With purpose and malice

Flesh of our flesh,

Blood of our blood

Aryan Supermen

Never a dud

Blood of the man gods

Pure hale and hearty

For sheer bloody mindedness

“Ve are ze Party!”

‘Hear! Hear!’ someone in the audience cried out.

Picking up the large inflated globe of the world I held it up to show the Eurasian land mass.

“As leader I’ll take you

For one mighty ride

Through Eastern Europe

And much more beside

We need living space

Lots of room to expand

For those babies we’re breeding

Who’ll need lots of land”

Did I not promise a miracle and is this not so?

To restore German glory to a forgetful world.

Let mountains and deserts tremble,

Let cities shudder,

Let our enemies in near and far places mark this moment,

Turn in fear of all those miracles, those scum,

Like wolves tearing into a herd of sheep,

that’s how you’ll come.’

I spun the globe around in my hands.

‘We’re part of an axis,

Around which friends rally,

A fortification

From which we may sally.

Our comrades in England

Will rise up quite soon,

Their state will be marching

To a different tune

The Union of Fascists

Is tagging along,

Forwards! Forwards!

Blare the bright fanfares,

They’re singing our anthem

Our Horst Wessel song”

As this point I hold up the ‘bloodstained’ flag, symbol of the Nazi martyr, yelping:

“Give up your pleasures,

Your lives for your country,

Futile gestures,

That from me

Is my ultimate advice

Regrettably, Volk,

As your mentor and saviour,

I only have vun life to

lay down for my followers ,

Only one to sacrifice”.

On that note, my rapid-fire delivery done and dusted, the audience leaping to its feet in a frenzy of adulation. I was rewarded with rapturous applause, outstretched arms and sustained‘ sieg heiling’. It went well into injury time—and not one person in that pullulating space would have wished it to stop. I had swept them off their feet. How much this was a response to my blazing display of bravura, or just showing off Nazi saluting and ‘sieg heiling’ that everyone has jocularly indulged in, I’m not sure. The showing off wouldn’t have come about if my audience hadn’t got something out of it.

‘Bravo!’ said Mr. Harry as I sank back exhausted into my chair, ‘put it there. Your delivery was so natural it seemed effortless. You inhabited Hitler’s character fully. You’ve captured so well his skill at allying highly abstract concepts with political, physical violence. You’ve captured the same denunciations and digressions, the same kinds of phrases that he used like motifs in a symphony. Seldom in history has so much depended on one man’s personality. Your take on him connected with me on a visceral level. I heard that mesmeric, inflammatory voice of his, the raucous crowds over the radio. These brought home the inevitability of war as much as the panic I saw on the streets of the Hague. That day, August 29, 1939 was the one on which the Dutch Government mobilised its armed forces against his. I was visiting the Hall of Justice of the Palace of Peace only to find it empty, the ideals it represented ransacked by Hitler. I made a vow there and then to help recreate these ideals whenever this evil tyrant was eliminated.’

‘Were you able to implement this in any way once the conflict was over?’

I had the good fortune to be a member of the Australian delegation meeting to form an international organization for the promotion of international peace and conference.’

‘The United Nations, no less. A delegation led by that man of grand ideals, Dr.Evatt. During this seminal period I was also able to work on the establishment and development of the International Atomic Energy Commission, weapons disarmament in the U.N. Commission for Conventional Armaments, and the drafting and adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.’

‘What a heady, hopeful time in history you were involved in.’

As for the value of my speech I believe I had caused the history of the headquarters to be more intimately acknowledged and understood. What mattered most was that I had played a tiny part in chipping away at the pedestal upon which Hitler has somehow remained. A testament to his mystique, it has continued to impress and mystify some, full of frustration and hatred. The very hard feelings produced by The Treaty of Versailles ending World War I, imposed requisitioning that the victors knew were impossible for Germany to sign off on. The past becomes more tangible when one experiences the environment in which it occurred.

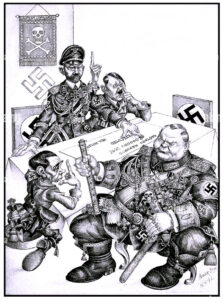

The war’s victors, who were determined to crush the German spirit by dismantling Germany’s military and consigning its people to abject poverty, thus helped to spawn Adolf Hitler.

This bully, gambler and arch manipulator rose to power on the backs of the wealthy establishment who, blinkered by its fear of the “enemy within” – Communism and the alien Jew, thought it could both control and use him.

After the Soviet bloc economies collapsed under their own weight, there would be concerns that his new generation of henchmen could get their boots in the door again. There would be fears they would widen the crack that feelings of subjugation and humiliation had created, manipulate people’s despair and unhappiness.

‘An enemy is at work’ the people are told there as elsewhere. A scapegoat is sought and hounded while the well off, anxious to defend their positions join in the hunt or look the other way.

Under the veil of “night and fog”, the streets outside this former academy would once again resound to the sound of boots – this time bovver not hobnailed, tramped on lockstep by screeching neo-Nazi romper stompers out to beat up blacks and Asians considered inferior.

Oy gevalt, this reverence for Hitler would even attract a following amongst some young Russian migrant golems in Israel itself. A scenario recognizably possible at other times, it continues to raise its ugly head in conditions of unemployment, social insecurity and poor education.

The ultimate in systems of state terror, its camps the lowest circle of hell, nothing can ever surpass the Nazi template in its pathological efficacy.

With respect to education, it succeeded supremely in exploiting the natural exuberance of the youth, their craving for action and spectacle. It offered them a sense of belonging. It provided an opportunity for many to develop superb physical strength unrestricted by traditional class barriers.

At the same time, its strangulation of intellectual life, its purging of any teachers considered politically unreliable, regardless of their proven head for teaching, resulted in academic insecurity and timidity which lowered educational standards disastrously. The gaining of knowledge by the youth is vital for future military victory.

National Socialist teachers of questionable ability indoctrinated students with propaganda which was then parroted back by their students as unshakable points of view with no room for disagreement or discussion. Newly hatched professionals lacked basic skills in maths and science. Biology had become corrupted bag and baggage. Nazi scientists would complain they were partially hindered in developing new sophisticated weaponry by the lack of trained scientific personnel. This would be central to the downfall of the ‘thousand year’ Reich. The torchlights guiding their processions through the Brandenburg Gate would be dimmed forever.

National Socialist teachers of questionable ability indoctrinated students with propaganda which was then parroted back by their students as unshakable points of view with no room for disagreement or discussion. Newly hatched professionals lacked basic skills in maths and science. Biology had become corrupted bag and baggage. Nazi scientists would complain they were partially hindered in developing new sophisticated weaponry by the lack of trained scientific personnel. This would be central to the downfall of the ‘thousand year’ Reich. The torchlights guiding their processions through the Brandenburg Gate would be dimmed forever.

Sunday Bloody Sunday.

While I was embedded with the British Army, a tragic event sent shockwaves through the divided city. Not in the expected flashpoint of Berlin but back in the home country. The Army was caught standing with a book of matches in its hands. The news was announced in January 1972 that British soldiers had shot dead thirteen unarmed civilians in a civil rights march in Northern Ireland. The event signalled an inflection point in The Troubles.

The British Army had earlier been welcomed by the nationalist community as a neutral force to protect them from the unionist establishment determined to defend its entrenched privileges. Coming on top of anger about the policy of internment, the effect of the massacre led to the perception of the Army as a force in collusion with the Protestant paramilitaries.

This reactivated the IRA, boosting recruitment and support for the Provisional wing. It helped them win the popular support that the Army thought was there all along. It provoked a spiral of violence and an intensification of the bombing campaign that would threaten all out civil war and spill over to the British mainland.

It caused some concern as to the capacity of the British to contribute effectively to countering the Soviet presence in Germany. Apart from the diversionary demands of a war on its own soil, this army relies on its Irish element. A good number of the soldiers into whose company I came were from Ireland. It has been said that the British Empire was won by the Irish, administered by the Scots and the profits went to the English. It was crucial for the military to prevent sectarian tension within itself.

The mood at the Berlin Brigade was appropriately tenebrous. The killings sullied the image that the Army was conscious of projecting – that of a restrained military force whose hands were clean.

I was interested in finding out how the tragedy appeared to those who looked at it from behind British guns and uniforms.

In the bar at the headquarters where I was free to drink, alcohol loosened off-duty tongues. I was able to witness a range of voices holding forth on the matter. Some had made a tour of duty in Northern Ireland and spoke of how they had been treated to tea and cake by the Catholics in the early phase of engagement. Otherwise, there was almost no social interaction with members of the community in which they found themselves.

I realized that this was what hindered them from learning about how members of the nationalist community – their own countrymen and women- were treated as an underclass. Some were aware of this and expressed cautious concern. I wanted to point out some inconvenient facts but thought it prudent to remain a keen observer. I didn’t want my motives to be taken the wrong way. This wasn’t a university debating society. Positions on the situation in Northern Ireland had become heavily fortified. Relations between soldiers and locals became marred by indifference, sullenness and anger, with soldiers pelted with stones and bottles, spat at or shot at. The official whitewash for Bloody Sunday – that the Army was returning fire – was putatively accepted. ‘There you go, the lads did a good job,’ said one soldier. ‘They did their duty and did it well.’ It would take a long time for this view to be discredited.

What the guys found hard to accept was how poorly prepared and ill-equipped for such a conflict the Army was. They didn’t even have enough riot shields. They chafed at the official justification of the intervention as being to provide a peacekeeping force. “The IRA didn’t see us in that light, so why should we see republicans any other way”. Most felt they were having to fight with one hand held behind their back. ‘We can’t beat them if we don’t have an even chance.’

They took it in turns to pile on about the republicans.

One suggested solution: ‘Collar the lot, lock ’em up and throw away the key.’

Another: ‘We need a leader prepared to let his dogs off the leash and give them room to run.’

‘Do you really believe that’s the solution?’

‘The question is ‘Who doesn’t believe it?’

Another, more strychnine laced, went, ‘If those IRA blighters think they can get away with their obscene outrages unhindered, they’ve got another thing coming. I’ll personally see it’s not catch and release.’

‘So what do you propose doing? You don’t seriously consider acting against the Geneva Conventions?’

‘You spoiled my surprise. I’ll take them out, and it won’t be for dinner. A few well-placed bombs left around Dublin would sort this lot out, teach em a thing or two, give their mothers something to cry over.. Blast me, break me, court martial me, hang, draw and quarter me, stick me on a gibbet, slap any charge you like on me-I don’t give a damn.’

‘Do you really think killing people makes things better?’

‘It’s a start.’

‘All prisoners have to be subject to due process. Before doing anything like you’re suggesting, they have to be protected and brought in for questioning. Otherwise you end up doing the same horrible things as them,’ I dared to say.

‘Instead of whingeing about the rights of bloody murderers, you should be more concerned about their innocent victims.’

‘The IRA feel Ireland is the victim of Britain. The British government has to remove inequality in the North and win the trust of those factions less hardline.’

‘The kneecapping comes first, the questioning second. There’s only one IRA member I trust. A dead one.’

‘They have to be tried legally and their motivations examined. Don’t you believe they should at least be read their rights?’

‘I’d read them their rites. Their last ones.’

‘Wouldn’t you at least listen to what they have to say?’

‘I wouldn’t be able to hear them. I’d be wearing earplugs to drown out their screams.’

‘Supposing, for argument’s sake, they don’t feel like talking?

‘Don’t worry, they will.’

‘They may genuinely have nothing to confess.’

‘By the time we’re finished with them, they’ll have confessed to starting the Crystal Palace Fire.’

‘There may be pathological reasons why some resort to terror.’

‘Is that so? Then The Reaper Company will cure it for them.’

‘Let me guess. Thumbscrews and hot coals.’

‘That’s too old school. We now know much more about anatomy and what the body can’t stand.’

‘They have it coming. Let me at them,’ said one soldier.’

‘Get in line,’ said another. ‘Though it’s too good for them we’ll carry out some surgery. We’ll run them through, rip out their larynxes, extract their tracheas, loosen their spines. We’ll perforate their pancreases. We’ll have their guts for garters, their heads on spikes. They’ll get the point. We’ll hack and mangle their legs with a rusty knife, feed their genitals to the wolves. We’ll flay them alive, hang them up from meat hooks, douse them with boiling water.’

‘I get it. It’s a retributive experience they won’t forget.’

All they’ll be able to do is pray for a quick death which they’re not going to get.

The last thing to go through their mind will be their kneecaps. We’ll drop them in the Liffey tied to anvils with their legs cut off. I’ll say to them, ‘Go on, you swim home now.’ Even Jesus won’t save them. In case they don’t drown, they won’t be able to crawl out. We’ll turn the subjects into objects. There’ll be so many rotting bits floating about you couldn’t put them back together even if you had the directions. They’ll be no more than bits of meat no dog would eat. They won’t be able to identify what’s left of them at Dental Records. That’s what you do to the killers that they are. It would save the government a pile of work.’

‘You’re a gentleman and a scholar’, I said.

‘I’m glad to hear that. I aim to please.’

‘You’re well up on your noble British military history.’

‘It leaves the others for dead.’

‘As a Christian, don’t you believe in showing forgiveness to your enemy?’

‘Forgiving them is God’s function. Our job is simply to arrange the meeting.’

‘When do you expect to carry out this arrangement?’

‘At a time and manner of our choosing.’

‘Doesn’t it bother you to have to kill others ?’

‘Not in the slightest. Men of conscience have no place in our business.’

This guy had totally lost himself. His gyroscope was gone. He didn’t know up from down, good from bad.

‘If you have any objection to this, speak now or forever hold your peace, ’he concluded.

All these young men felt this wasn’t the kind of conflict they were expecting the army to be involved in when they joined up. They simply wanted a good old-fashioned war like in the Boy’s Own Annuals where you could go from the subs bench into the scrum, get stuck into the enemy, blow them to kingdom come, and if you were a jammy beggar, come home to a hero’s welcome. The Falklands having more oil around it than Britain, such argy bargy would have to wait till Margaret Thatcher.

The front line is always changing.