‘A new world will be won not by those who stand at a distance with their arms folded, but by those who are in the arena.’ ~ Nelson Mandela.

“The greatest glory in living lies not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.” ~ Nelson Mandela

In the lead-up to the 2000 Sydney Olympics, a forum was held at Sydney University called ‘What makes a champion?’

On learning that the guest speaker would be none other than Nelson Mandela, I made it my business to attend this function to meet the man formerly nicknamed ‘The Black Pimpernel. I wanted to offer my services and to get across my ideas on this theme. Moreover, seeking a more secure funding base, to get my lucky break, being courted by some enlightened philanthropic patron.

To ease my way in I prepared a brochure in which I drew particular attention to the role that eugenists have played in both South Africa and Australia in lobotomising people’s functions. Cry our beloved country too. Nominating myself as a contender, I threw my hat in the ring to challenge eugenist educational practice.

An opponent of this practice, so damaging to his own country, Nelson recognized education as a great vehicle to bring equality of opportunity to the world.

Throughout his long life and even his imprisonment, he made a point to keep educating himself – seeing learning as an escape from his confines.

He inspired his fellow prisoners to do the same: “At night, our cell block seemed more like a study hall than a prison… Robben Island was known as ‘the University’ […] because of what we learnt from each other”.

He appreciated the limitations of formal education. Despite earning both a Bachelor of Arts and later a law degree, he realised that they were neither a passport to career success nor wisdom. He remained humble about his achievements, saying that despite others’ lack of formal education, they could be “my superior in virtually every sphere of knowledge”. His humility influenced his thinking on politics and the democratic rights of his fellow citizens: “To a narrow-thinking person, it is hard to explain that to be ‘educated’ does not mean being literate and having a BA, and that an illiterate man can be a far more ‘educated’ voter than someone with an advanced degree”.

Aware of Nelson’s penchant for boxing, I featured on the cover fighting poses by two knockouts. The first was Mohammed Ali who refusing to kill Vietnamese who never caused him injury was made to pay a high price.

The second was Cuban Alejo Carpentier who fought unpoachably, not for money but for his country, one Nelson sees as instrumental in bringing apartheid to an end. On the inside of the brochure I spoke of Nelson’s legendary intestinal fortitude and determination in his twenty-seven years in jail.

I linked it to that apotheosis of the human spirit I have touched upon earlier in this book – that of Leonard Cheshire and Edmund Hillary and the masses of unsung heroes who make the world a better place.

After touching down in Sydney, Nelson was driven to his press conference where I waited with a small thicket of well-wishers. The focus of my attention was his security squad who swiftly but unobtrusively took command of the terrain. The logistics of moving and closely protecting this man who had disturbed the tranquil lifestyles of the white masters were being played out before me.

Moving in and out of the building, they were casing it down to the studs, as they must have done in numerous locations throughout the world. I approached the guy who appeared to be directing operations with a view to him passing on my brochure to Nelson. After I explained to him its nature, Adine assured me that he would, placing an extra copy in the book on Kakadu tribe and land that was to be presented to the guest of honour.

Cometh the hour, cometh the man. Arriving by limo, looking as usual right for the part, flamboyant in his gold-coloured Batik shirt, the eighty-two year old president looked beat from his long flight. He waved somehow and called out a greeting. I noticed the tone of his voice, low, flat, worn and tired. Just like people should sound after the long hours in the air. He was happy to be in Sydney, but would be happier to be in bed. The man of the hour had to be helped into the conference centre.

When he emerged at the end he appeared visibly perked up, flashing his broad winning wide white smile which was almost too good to be true, that which had lit up the world. He was just about to get back in the limo when I shouted out heartily “Viva Nelson!”

Unable to resist this encore, he came over to extend to me the hand that had rocked the world. He then directed himself to the toddler in the stroller next to me. He had long been shut off from children whose company now made his day and for whom he raised funds. Just as well I had passed my brochures on before as, everyone wanting a piece of him, a scrum had formed around this unlikely rugby supporter to shake his hand.

Passing on my offering through his bodyguard was enough for me. Adine was in my eyes a paladin of just as much interest as his trusted leader. He wouldn’t have hesitated to take a bullet for him. They were a team whose very lives depended on one another.

After rescuing their charge, the entourage moved on to Sydney University where I caught up. Positioning myself at the edge of the black-tie jamboree and gradually moving in, I sidled up cheek by jowl to hobnob with and buttonhole anyone who was anyone, the well-heeled and famous, movers and shakers of the Australian social register, handing each my brochure.

My uninvited presence perforce came to the attention of the organizers and university security who pounced on me anxious to know what I was up to. If any terrorist were to take out those gathered, who would rule the country? When I asked them to look at what I had written, they realized I too was an arriviste, albeit one of lesser means and fame, seeking just to make my bid, and in harmony with the occasion.

Having been granted this freedom of expression, it was my pleasure to listen to Nelson deliver his moving speech on championship. Even with a galaxy of celebrities in the Great Hall, the current seemed to carry everyone to him. “One of the most difficult things is not so much to change society” said this great changer of society “but to change ourselves.” Speaking slowly and carefully choosing his words, he explained that black people in South Africa had to change themselves in order to sit down with their white oppressors. Otherwise their country would have gone up in flames.

Asked whether Australians should look more at their history of black-white relations, Nelson was diplomatic. He said the situation was different – blacks form the majority in South Africa but a small minority in Australia, adding “I have confidence that you have men and women who are capable of resolving their own problems.”

Jack Thompson, the actor, presented Nelson with a framed, autographed photograph of another champion, Sir Donald Bradman. Sir Donald’s message was that he “revered” Nelson for his courage, integrity and compassion. Nelson said South Africans were tempted to regard Sir Donald as “one of the divinities”.

He said that the great arsenal of knowledge and capacity generated by the advances of the century were not used effectively to combat inequity. “We closed the century with an even more marked distinction between the powerful rich nations on the one hand and the poor and marginalised on the other. The majority of the people on the planet continue to languish in poverty.

That the century closes in that manner is the more disappointing considering that it was also an era marked by the presence on the world stage of so many champions of freedom and equality.”

He said it was his fervent hope that the excellence of achievement and the dream of friendship would at least meet in this century to create a “brotherhood and sisterhood where all share in the fruits of our great advances and achievements.”

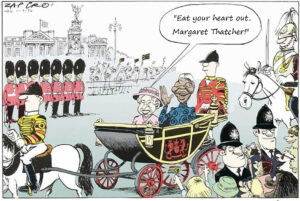

This master at winning over even the most implacable opponents had shared such a bond with the Queen, enjoying their “warm friendship” and time after time referred to her as “my friend, Elizabeth”.

He did after all himself come from a royal, chiefly family.

At the end of the forum I spotted Malcolm Fraser nearby in the open quadrangle and discreetly worked my way close to him. Unlike Mrs. Thatcher he had supported the Commonwealth sanctions against apartheid South Africa.

He had refused permission for the aircraft carrying the Springbok rugby team to refuel on Australian territory en route to their controversial 1981 tour of New Zealand.’ No one could accuse him ever again of being all mouth and no trousers despite him having turned up without the latter in a Memphis hotel.

‘Do I have the pleasure of speaking to the 22nd holder of the great office of Australian prime minister?’ I asked him.

‘The pleasure possibly, the intention certainly.’

‘You must be thinking of your uncle today,’ I said. Fraser’s uncle, was a noted sportsman who rowed for Australia at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm.

‘I certainly am. He trained extremely hard to win his place. Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity. I must say you’ve done your homework.’

‘I have. Not just on your personal life but on some of the principled decisions you’ve made which haven’t gone down well in your party. I’d like to thank you for having adopted your formal policy for a humanitarian commitment to admit refugees for resettlement.

‘Certain actions are not easy to take but have to be taken. It’s always rewarding to be appreciated for them. This was one of them. ’

‘You met President Mandela when he was still in jail. What were your impressions of him then? ’

‘I found him to be by far the the greatest person I’ve ever met in my life. He is a far, far better man than me or anyone else I’ve ever known.’

‘ That’s high praise coming from you. In your estimation what makes the ‘best’ person the best?’

‘I don’t think he would have known what it was to lie. He had a sense of ethics, a sense of purpose, a sense of integrity, a sense of justice and fairness which were built in the man.’

‘You reached a very different estimate of him than Margaret Thatcher. She said before the transfer of power she would never see anyone from the ANC which she labelled a terrorist’ organisation. Yet while under pressure to call for his release from jail, she maintained no reserve in travelling to Chequers to meet with his jailer, P.W. Botha.

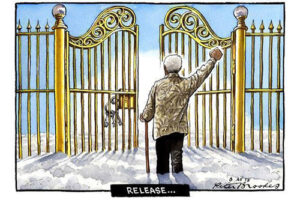

‘You have to keep in mind she had very strong entrenched views on the ‘armed struggle’ and demanded the ANC abandon it. But she was fully aware the system of racial discrimination had to go. She did not waver from her opposition to Botha’s policy. She would be forced to conclude that in any negotiations on a transfer Nelson Mandela would be leading a totally united group behind him. The reception at Chequers may have helped build confidence, allowing Botha’s successor to make the fateful decision to release Nelson Mandela and finally signal the end of apartheid.’

Then I had the good fortune of standing by and chatting with Edmund Hillary. I explained to him the nature of my work and overcoming the ministerial obstacles to freedom of speech.

‘These politicians are so expedient and just plain slippery,’ he said.

‘What do you hope to achieve in taking them on?’ he asked.

‘To knock the bastards off,’ I said, using the same sentiment he used about beating Everest.

‘I hope you come up trumps and reach your objective, Allan. Whether it’s climbing a peak, reaching the Pole, leading a movement or setting up a school, the same elements are involved. You need to have an ego to start with for sure, but not to let things go to your head. Like Mandela you have to be confident of what line you are following.’

‘Was this instilled in you at school? You went to a leading grammar school, didn’t you?

‘It wasn’t instilled at my country primary school where I was humiliated by teachers, called a ‘sook’. Later I was academically and emotionally lost in the city grammar school I attended. I had to prove myself in the face of discouragement. In the first week a physical education teacher cast his eye over my scrawny physique, rolled his eyes to the heavens, and muttered: “What will they send me next”. He didn’t know or care that I had cauterised my feet by walking barefoot the kilometre to primary school.’

‘That sounds extreme. It must have been hard on your feet’.

‘You’d better believe it. Each day wet, fine or frosty. But let’s face it, our feet were designed to work without shoes. Maoris and aboriginals were able to run great distances barefoot with virtually no pain or injuries. This is why Kenyans and Ethiopians make such great long distance runners.’

‘And your P.E. teacher?’

“He placed me in the misfit class with the other physical freaks. I developed a feeling of inferiority about my physique which has remained with me to this day, not about what it could achieve but a solid conviction about how appalling I looked.”

Then through my teens, my gangly body sprouted – nine inches in two years at one point – and though my long daily train trips to school denied me the chance to play sport, I found my long suit by running alongside the train and leaping on at the last moment.’

‘Nelson did a lot of running too , Sir Edmund, apart from running from the police. He understood the importance of keeping fit to maintain positive mental health and like you took up long-distance running while a schoolboy. He says that exercise gave him ‘peace of mind’: “I have found that I worked better and thought more clearly when I was in good physical condition, and so training became one of the inflexible disciplines of my life”.

Even during periods of his life when he was in hiding, he would make a habit of changing into his running clothes and jogging on the spot for over an hour.’

‘Running teaches us the value of hard work and discipline in achieving one’s goals.’

‘So it got you interested in climbing.’

‘That developed when I was 16 following a 1935 school trip to Mount Ruapehu , after which I showed more interest in it than in studying.

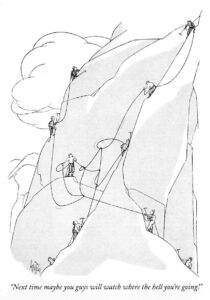

‘You eventually joined roped teams so as to secure each other against falling.’

I learned how critical it is to collaborate with others. Such teams require good co-ordination. with each other. And co-ordination with other teams.

‘What do you see as the most important requirement of a successful mountain climb?’

‘No question about it. Proper planning.’

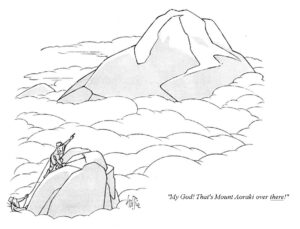

‘What led to you taking on the highest peak in the world?’

‘Ascending the highest ones in New Zealand whetted my appetite for the big one.’

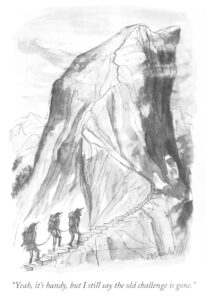

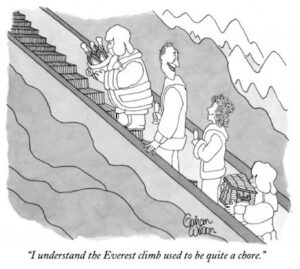

Of course getting to the top of mountains like Everest is much easier today.’

‘After your eventual ascent of it your confidence in yourself must have been boosted no end.’

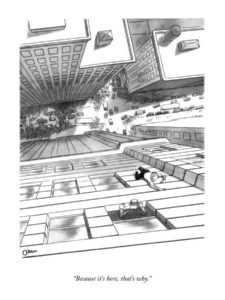

‘I came through in challenging myself. I craved to repeat this, whether to get at what lay inside or to repay those who helped me. I learned to weigh the risk to life and limb involved in these initiatives and to enjoy the journey. Each success took me to a higher level, positioned me strategically for the next move.

‘What did you learn in the process?’

‘I learned more about myself and my surroundings. Even the mediocre can have adventures and even the fearful can achieve if they drive themselves. All humans whether individuals or as a species need to challenge themselves to find out more about the world and their place in it.’

‘You sound like a regular Mandela, I said, quoting lines from Long Walk to Freedom I had memorised: ‘I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can rest only for a moment, for with freedom comes responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not yet ended.’

‘You could say that Nelson is my mandala. Few, myself included, will rise to the challenge as he has , and few will journey such a long way. But in any sphere you care to mention, be it politics, the arts and sciences or sport, you’ll find the same spirit of adventure fuelling advances.’

‘How did this apply to setting up your schools in the Himalayas? I asked.

‘Founding these schools was an uphill battle. And don’t forget, as in climbing, the most difficult part is in the last few steps. It’s then that anything can go wrong.’

‘So how did you make it?’

‘I couldn’t have done it without the cachet I derived from my climbing and trekking. This opened many doors, enabling me to twist the arms of otherwise hardnosed businessmen into parting with dollars for these projects. Keep in mind the words of Marie Curie: ‘Life is an adventure or it is nothing at all.’

‘What daring experiences do you engage in these days?’

‘I love to spend time in my garden tending my roses.’

‘So what feat can I achieve to parlay into getting backing for achieving universal literacy in Australia – to show in the process that great intellectual achievement is possible for anyone? As you were the first person to reach both poles and the highest peak in the world, I have to rule out both these avenues of newsworthiness.’

‘You might have to consider reaching them backwards,’ he laughed as we adjourned with the others for refreshments.