From ‘Hamlet’ to Global Village

My studies in literature, particularly in drama, would lead to me becoming better versed in the ways of the world. They would transport me far beyond the cosy down-home world of familiar settings and normal characters with a nice way about them, or at least beyond one in which a handful of fellow Caucasians sharing my protected background would cushion me from culture shock. Growing away, off the straight and narrow, well lit path to include the demi world, the jungle out there, not necessarily in a foreign clime, inhabited by a multitude of strangers whose skins we have to enter to understand. I could rattle off the list of usual suspects who through volition, coercion or neglect find themselves cast adrift in a messy, lawless world of uncertainty and disaffection, securing rungs on the lowest ranks of the social order, their lives largely unmanageable. Hoi polloi, the great unwashed, underlings, knockabout characters rough around the edges who are not so nice, may exhibit extreme behaviour, unpleasantness and lack of refinement. Characters who may not be family oriented, ne’er –do-wells always strapped for cash, no visible means of support; flotsam and jetsam crowding hard-edged streets; troublemakers, losers, outsiders, outliers, rejects, freeloaders, pariahs, fugitives, misfits disrespectful of authority, outspoken, restless and assertive, ‘undeserving’ of their station in life, obeying their own code of ethics, violent in their language and actions, shifty gadabouts drifting and grifting, no boundaries to keep them in check – all reflecting conditions other than those of the soporific village.

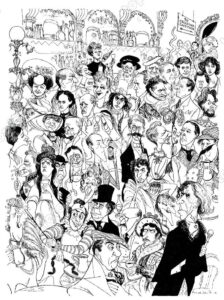

Such characters of all shapes and sizes would abound in the pages of my set texts, in the reels of films I viewed, and in all my born days, revealing themselves as variations of types that recur through space and time. I would come to revere the Bard in particular for the wealth of characters he created to bring about the twists and turns and subtle nuances within his ageless dramas.

I would seek out and cultivate these who I considered living actors of the first magnitude. I would pay close attention to those I considered the most accomplished interpreters of the Bard, those who had the Midas touch at making Shakespeare accessible to an audience. They would be possessed of special qualities – a deep knowledge of language and dramatic conventions, an expressive voice, a vivid imagination and the emotional reach required to inhabit his characters and speak, as they would. These artists would be equally adept at wielding both iambic pentameter and a broadsword.

The Crowning Touch.

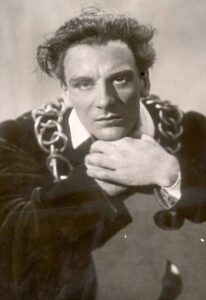

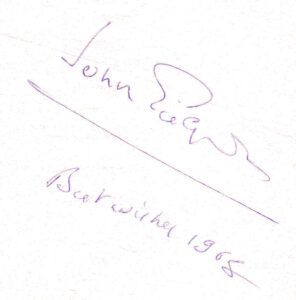

One of the most respected actors of the 20th Century and winner of a special Laurence Olivier Award for services to the theatre was John Gielgud. This lion of the stage contributed enormously to theatre for his extraordinary insight into the writings of Shakespeare. Acclaimed as the high-water mark of English Shakespearian acting, he moved it in the direction of naturalness. Gielgud revolutionized the role of Hamlet with the speed of his delivery.

He also made his reputation as Romeo, , Shylock, Lear, Cassius, Prospero and Richard II.

I saw him at one of his sell-out one-man performances in Sydney, delivering a collection of excerpts from Shakespeare’s plays. The colloquy of speeches shows the journey of life from birth to death.

I found his mandarin accented plummy voice, which Olivier called “The Voice that Wooed the World”, wonderfully expressive. ‘O, it came o’er my ear like the sweet sound that breathes upon a bank of violets.’ Demonstrating as no one else how Shakespeare should be spoken, he melded ‘the power to convey subtle movements of the spirit, delicate shades of thought, the inner workings of mind, with an ability to tear off a “passionate speech”.’ This gave a sense of his real quality, despite a somewhat inexpressive physique. His arm movements were inclined to be jerky. He added a suggestion of fluidity in his gestures by carrying on stage a big white silk handkerchief. With that inimitably erect posture of his, he held his head at a slight angle as if he were listening to an inner voice.

After the show I joined the group of well-wishers greeting him outside the stage door. The matchless verse-speaker emerged to greet us, his coat draped over one shoulder and wearing a flower in his lapel. I could sense immediately what Olivier once said of his aristocratic mien, both on stage and off: “John has a dignity, a majesty which suggests that he was born with a crown on his head”. He bowed regally when a well-wisher presented him with a green umbrella. As he walked off, or more accurately tripped off, I saw how telling his childhood tendency to flat-footedness was. Cheated by dissembling nature, at school he proved rudely stamp’d, curtail’d of this fair proportion, nary shaped for sportive tricks. His drama teacher had observed that he walked like a cat with rickets. He counteracted this distemper by bending his knees slightly.

Then haply as chance would have it, I came upon him on his own, in a café near the theatre in the act of potation. He looked up from his crossword puzzle. Recognising me from just before, this intellectually elegant actor, putting on a mock double take, said ‘Don’t I know you from somewhere?” Then after some seconds, he said: ‘Ah, come to think of it, you’re the young well wisher from the stage door’.

‘I am, unless I have stolen the role.’

He invited me to join his distinguished company. ‘Take a pew,’ he said, eating a piece of cheesecake and washing it down with tea, ‘you have a lean and hungry look.’

‘Don’t let me interrupt you, Sir John. If food be the music of love, prithee eat on’.

‘Not a problem. I don’t mind company. I’m used to talking while eating. Now what would you like for tuck?’

‘Well, like the tapeworm said to his host, I’ll have what you’re having.’

When the waiter fronted up to ask what I wanted, I replied, ‘I’ll have what the gentleman’s having,’ pointing towards Sir John’s fare. The waiter waggishly proceeded to slide Sir John’s cake towards me, slowly enough to evoke a laugh before sliding it back. He obviously had served the thirsty thespian before and knew him to be of playful jest, of most excellent fancy.

‘Marry, are you a comedian?’ he asked the waiter.

‘One in waiting, my profound friend. If I do not usurp myself, I am. The day I was born I took a bow. When the doctor slapped me I thought it was applause.’

‘You believe acting is your calling.’

‘Truly.I’ve long heard the cattle call. Like you I come from a long line of actors.’

‘Does it have a name, this line you speak of ?’

‘It has. The dole queue.’

Sir John then asked me, ‘How would you like your tea?’

‘Hot, strong and in a cup if you please.’

‘You must get up quite a thirst talking so hard, Sir John’, I said, seated facing what was perhaps the finest actor, from the neck up, in the world.

‘True, True, ’he replied, holding his tea cup a tad stiffly in his large bony hands, ‘and so long. I’m a trifle peaked. I’ve been performing this recital for the last eight years. All over the world.’

‘Doth thine ears quiver and thine head shaketh when thou speaketh?’ I said, bunging it on.

‘Only when there’s not enough bums on the seats’, he replied.

‘Thou dost protest too much, methinks. Gladly your repertoire extends far and wide,’ I commented.

‘And deep too. ’he replied in a grave demeanour. ‘Six feet to be precise. This year I played Sir Francis Hinsley, doyen of the colony of chooms in Hollywood,’ he said. ‘This part in ‘The Loved One’ gave me fine opportunities as a corpse. My instructions were somewhat different to the usual.’

“Give it a dead pan!” I put forward, quoting the movie gangster who doesn’t want the man on the other end of the phone line to inadvertently alert anyone else in the room as to the importance of what he’s about to be told.’

‘The Gay Bride’, said Sir John, recognising the movie. ‘No, I actually had to pull faces, at the touch of the embalmer’s fingers,’ he said, screwing up his face.

‘You played opposite Peter Ustinov in the stage version of Dostoevsky’s Crime And Punishment.’

‘Peter played the detective in that legendary production. That was right after the War. Whenever Peter and I meet up, we invariably end up reminiscing about it.’

‘You co-directed with Noel Coward and starred in ‘Nude with Cello’.

‘No, ’he corrected me. That was ‘Nude with Violin’.

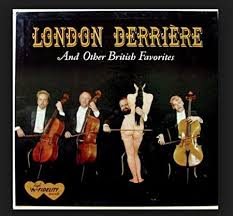

You’re confusing it with the one appearing on ‘London Derriere’. The gimmick record cover features a nude being bowed.’

‘In faith you’re right. I was given one. The insert states “I bought this album for you as a gift. Sorry, I couldn’t afford the record! What kind of music do you think I didn’t get to hear?’

‘I’d say Bach’s ‘Air on a G-string’. That is in a full dress rehearsal.’

‘You appeared on the screen in ‘Saint Joan’ in 1957. As the Earl of Warwick.’

‘Alack, it was figuratively seared at the stake by critics and filmgoers alike, ’he judged, staring into his cup, a little mournfully. ‘My classical style of acting has somewhat gone out of fashion. That was a rough ride for me.’

‘A rooster one day and a feather duster the next. Did you ever think of retiring?’

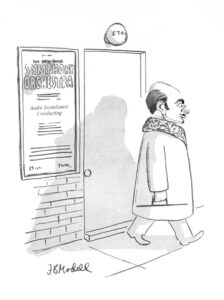

‘You don’t retire in our business, you just notice the phone hasn’t rung for several years. One day you’re at the top. The next in the tip. My career tended to flicker and fade like a faulty light fitting. I’ve been seen by many as an antique, something that belongs in Madam Tussaud’s. In the time of the Angry Young Men, I was neither young nor angry. The era of rebellion against the cultural Establishment was at hand. The kitchen-sink literary revolution spread to the theatre.’

‘Heralded no doubt by the Royal Court’s staging of John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, ’ I suggested. What did all this betoken?’

‘My life upon it, it rendered old troupers like me passe. Unlike for Larry Olivier, who reinvented himself with his characterization of Archie Rice, it was a new world in which I was out of suits with. I could never play peasants or workmen or anything in dialect.’

‘So your roles dried up.’

Even in Shakespeare I could never play an earthy Falstaff or a martial Henry V. I was seen to be behind the times – caught in amber. In the last of the ages of man.’

‘You can’t mean the last one according to Shakespeare? ‘Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything. Or ‘’youth, middle age and “Gee, you look good.” Or the penultimate one of the seven ages: ‘spills, drills, thrills, bills, ills, pills and wills?’

‘No, the fourth in the abridged version: infancy, childhood, adolescence and obsolescence.’

‘To what quality of yours do they attribute this?

‘On the screen some have perceived me as being supercilious.’

‘Supercilious?’ I queried, ‘wondering to myself if it meant ‘very silly’. ‘How now?’

‘Haughty, stuck up,’ he explained.

Sensing him, known fondly as ‘Johnny G. ’ to be anything but that, I offered him, camping it up a bit, one of my jokes, triggered by that word’s first part : ‘A policeman enters his station and greets one of his his colleagues, “Morning, ‘Super’, whereupon the superintendent replies, “And the top of the morning to you, ‘Wonderful’. Sir John snuffled, a great smile suffused over his dial and he tightened his cheeks. He still had a mouthful of tea. I was afraid for a second this this vocally melodious gob was going to spray it everywhere. After swallowing it, he whickered his amusement impishly before letting forth a burst of deep loud hearty laughter.

‘It behoved me to stick to what befits my composition, dear boy’, he continued after regaining his composure. ‘I took to the road and, abracadabra, here I am in Sydney with ‘The Ages Of Man.’

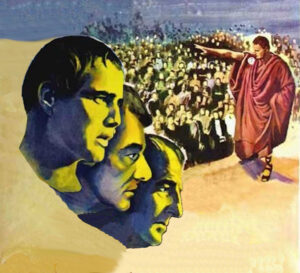

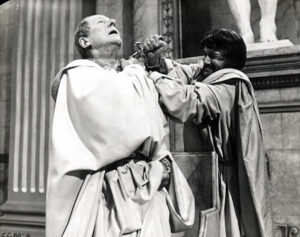

‘I’m glad I‘ve seen your performance other than in films. You’ve been in umpteen films, yet you’re not so well known for these. Your role as the devious Cassius in Julius Caesar (1953) next to Brando was a brilliant turn.

Your cameo as Clarence in Olivier’s Richard III was a real gem.

But it’s for the stage your genius is reserved.’

‘That’s very flattering of you. To a unique degree my proudest performances have coincided with the greatest plays.’

Richard II is famous not just for it’s pictorial qualities but by the beauty and exquisite melancholy of the poetry. You had an obvious affinity with the highly cultured royal patron of the arts.’

“The role of the young, headstrong and self-absorbed king luxuriating in his downfall always attracted me. Richard was a shallow, spoiled young man, vain of his looks, with lovely things to say. I fancied myself no end in the part, but even that seemed to help my acting of it.’

‘The Winter’s Tale’ is another great example from the Shakespearean canon. You played the part of the unsympathetic king in a nuanced, highly esteemed performance.

demonstrated a jealousy that mounts from an initial quietness to one that reaches fever pitch .’

‘That is a good observation. The stage enables me best to to spin it out of myself, like a spider. I’m an actor, not a star. Films pay the bills but they are not my passion. The work is too fragmented compared with the routine of the theatre. I don’t like the idea of how long it takes to reach the audience.’

‘That sounds like Burton talking’, I said. He doesn’t make a secret of his preference for playing on stage over the movies. He said, “In a film you’re a puppet, on a stage you’re the boss”.

‘What I really hated was the talkies’, he said, tilting his chair backwards, ‘having to lie supine and helpless in the make-up equivalent of a dentist’s chair while all these make-up people and attendants pawed and clawed at me, ’ he said, patting his shoulder, slapping his back and pretending to paint his face.

‘This must be very different to working on The Ages Of Man, ’I said, ‘this being a one man show’.

‘Tell me about it’. he replied. ‘Eight performances a week all by myself and sitting alone in a dressing-room between acts can be a very lonely business.’

‘Into each life some rain must fall.’

‘I’ve been in more hotel single rooms with tables for one than Gideon’s Bible. There are some lonesome towns all right. I fear I will be out of practice when it came to acting again with other people.’

‘Touching the matter of Hamlet, you’ve played this role a lot, haven’t you? Even at the castle in Elsinore.’

‘I’ve played The Prince of Denmark more times than you’ve had hot dinners’, he said.

‘By the time I’d finished with it I had the dithering Dane coming out my ears. I did not want to read, write, or talk about it anymore with anyone else.’

I turned down an amateur dramatics society offer to play Hamlet,’ I said jokingly. ‘To hell with them small towns, I’m off to Sydney. I also rejected an offer to act in ‘Thesaurus’, a play on words.’

Would you believe I turned down an offer in the mid 30’s from Alexander Korda to film his superlative Hamlet.’

‘Then again you’ve always had other Shakespearean roles waiting in the wings, haven’t you’.

‘These have always been the first talking points with people I’ve met. Socialites, monarchs, presidents, even J. Edgar Hoover wanted to talk to me about it. ’

‘J. Edgar- in the flesh?’ I asked. ‘That must have been interesting. When was that?’

‘It was before the war when I was in Washington. I spent an afternoon talking about Shakespeare with him before he became head of the F.B.I’

‘I’d have guessed he too was interested in dramas of brutal murder and mistaken identity. But cross-dressing! I can just see this head of the G-men dressed as Elizabethan acting dictated- as a female, ’I said, ‘complete with G-string’.

‘Fa la la. You’d be surprised how strong the urge to dress up is. Even by this toughest of He- men.’

‘He might do it to go undercover disguised. You could use him in any future production of Much Ado About Nothing. You know how to employ the use of masks and disguise to great effect.’

‘He has a compelling sense of himself as a serious, straitlaced Sherlock who never reveals his true feelings. A man like that would be concerned about letting his mask slip.’

‘What is he really like?’

He’s extremely well read. Beside him I felt woefully ignorant.’

‘I’m sure you delighted the pants off him with your own special knowledge. It’s innocence when it charms, ignorance when it doesn’t.’

‘That’s kind of you to say.’

‘Are there any Shakespearean roles you’d like to have a go at?’

I’d like to fill the Caesar slot itself rather than that of the leading instigator of the plot to assassinate him.’

‘Ye gods, that’s a shocking way to die. Stabbed to death by fellow senators who justified their treacherous crime saying Caesar bled ‘for justice’s sake’.’

‘At least there was this aspect to it. He died surrounded by friends.’

‘You could be seen as having helped make the careers of a new generation of actors, including Laurence Olivier before the war.

‘The Sweet Swan of Avon turned Olivier’s struggling career around in the mid-thirties. London was undergoing a Shakespeare revival.

‘A case of ‘Avon Calling! ‘’I said. ‘A mercurial actor with his matinee idol looks, to come to the fore and take the theatrical world by storm.’

‘That I encouraged him was only fair’, he continued. ‘I was born under a lucky star. The stork delivered me to a theatrical family, which gave me a head-start as far as my career was concerned. But I needed encouragement too. My first professional role was at the Old Vic as the English herald in ”Henry V” involved one line only, but that was enough to create a poor impression. I was advised by some to close up shop, It was Sybil Thorndike who got me to keep going.’

‘It’s often said that you and Olivier are rivals for the title of Greatest Shakespearean Actor of the 20th Century. One camp feels that in this nip and tuck, you have the poetic edge due to the beauty of your phrasing and more cerebral interpretation of the Bard.’

‘Larry’s more versatile than me, more electric, all action, but I’ve never thought of him as snapping at my heels. I’ve never had to feel jealous. I’ve always tried to be surrounded by talent greater than mine.’

‘Yet you’ve received many awards in your time.’

‘I don’t deserve these awards, but I’m pigeon toed and I don’t deserve that either. I don’t believe in prima donnas and grandstanding. I’ve never had aught but admiration for Larry. We alternated the parts of Romeo and Mercurio in Romeo and Juliet.’

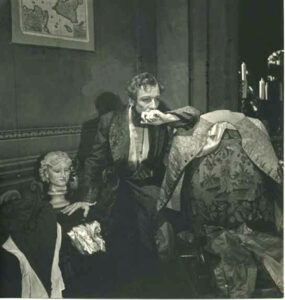

‘And you were both captured on camera in this role by Cecil Beaton .’

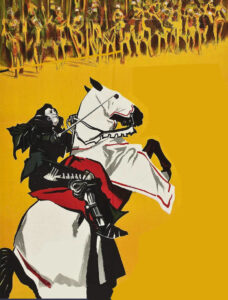

Larry’s a more versatile actor than me, having more power and attack, and a wider range of expression. He cuts a dash for the flamboyant physicality of his approach. As Romeo, he was able to conjure magnificent physical attributes almost effortlessly.

This compared to my reflective approach and my own painful contortions. Cecil was always expert at covering up any defects of his subjects.’

‘You of course are agreed to have the finer voice – especially for poetry – greater poignancy, and more subtlety. As for your your limitations, you have accepted them with grace.’

‘What was the point of fighting against it?’

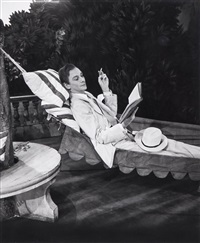

Instead you took it lying down. Cecil showed this in his picture of you spine-bashing as useless Eustace in The Return of the Prodigal.’

I had to keep my energies in reserve for my future collaboration with Larry. We both appeared in the screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s Richard III.’

‘A role you made his own, ‘I said.

He was Malvolio in the ”Twelfth Night” I directed.’

‘I admire Olivier too. I think he’s arguably the First Player of our time. Present company excepted, of course’, I said with a grin.

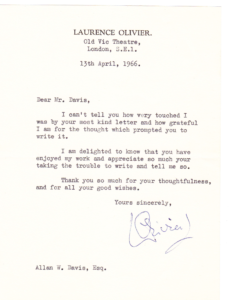

‘You should let him know-and why. No matter how old we actors get, so long as the grass is green and the earth still spins on its axis, we need encouragement from followers like you. You are our heroes. Larry will try to reply to you. He’s well penned and writes rattling good letters.’

‘As good as Beaton’s pictures, I imagine. You’ve been so often photographed by Mr. Beaton.’

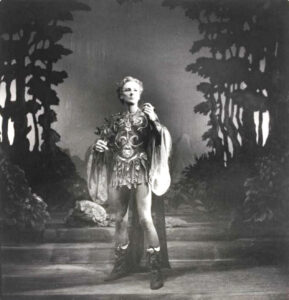

‘Cecil is a dear friend of mine. He’s covered my career with a series of portraits. At the end of the war he recorded my role as Oberon, The fairy king in ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream.’

‘He captured your plight well in ‘Love for Love’, where you as Valentine are locked up in your chamber to escape your creditors.’

At that moment the waiter came over to our table again. ‘Gentlemen, I hope you’ve been enjoying your repast. Sir John, excuse me for interrupting but do you see those two men dining over there in near the window. The one in the blue shirt is my fellow student from drama class, Peter. He’s with a theatrical agent who could land him his first big job. now you know more than anyone the importance of an actor getting that lucky break. Peter wonders if you could do him a favour and put on a little act. This agent would be greatly impressed if you stopped by their table before you leave and greeted Peter.’

I’ll see what I can do,’ replied Sir John,’ upon which the waiter withdrew.

‘Peter must know how you got one of our theatrical greats his lucky break, I said, ‘After World War II, ‘you proved a generous mentor to a young de-mobilized R. A. F. enlisted man, Richard Jenkins.

‘I predicted great things for that spoiled genius from the Welsh gutter, as he refers to himself. That thespian wastrel From Pontrhydyfen near Cwmavon.’

‘How can you say that?’

‘Just remember that in Welsh all the letters are pronounced.’

‘He had it all to start with, didn’t he.’

‘Taffy had a lot going for him: stage presence, startling rugged good looks, those eyes, a bottomless well of energy, and that fine commanding basso voice, suffused, as he put it, with ‘coal dust and rain’. In my production of The Lady’s Not for Burning he was launched as Richard Burton. No longer would he just add colour or intensity to a scene here and a moment there; from then on, the weight of the narrative would rest on his muscled and toned shoulders. The critics stood agape in the lobbies. A born actor, called the natural successor to Olivier, he became a star overnight.’

‘He had a lot to overcome, didn’t he, this pock-marked, lugubrious Welshman from the Rhondda Valley.’

The very idea that this man all ‘pustular and acne’d and angry and madly in love with the earth and all of its riches’ -as ‘Rich’ once described himself- could be a movie star seems fanciful in the extreme.’

‘You’ve remained close, I believe.’

‘We’ve remained friends ever since. I was privileged to direct him last year in my Broadway production of Hamlet.’

‘His voice lent dignity to even the corniest dialogue. His reading of Under Milk Wood made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up!’

‘I got the same adrenaline rush when dear Sybil Thorndike joined him in the first complete stage reading at the Old Vic in 1954. They went over and over it in rehearsal.

’

‘Together they caused my heart to race and my palms to sweat.’

‘Thou wert with Richard on the screen last year in ‘Becket. ’’

‘Only a whit’, he said, ‘but very rewarding.

‘He’s making as many headlines as a man sleeping on a corduroy pillow. Being an actor is not just what you do. It’s who you are. Sadly, he’s rarely out of the news- for the wrong reasons.

‘Rich’ shows signs of becoming dissolute, wild, prone to scandal.’

‘His decline has become a major spectator sport.’

‘He’s always plastered.’

‘So are some of the most splendid edifices in Europe but they have to be well maintained.’

‘He’s fighting an uphill battle with the bottle.’

‘Alas, a losing one, I fear, ’sighed Sir John, ‘‘he certainly can put away the drink and consequently looks terribly coarse and heavy. That’s not to mention the potential to waste the towering gift placed in him by the gods. Poor notices speak of him as a flash in the pan, that movies such as Prince of Players were terrible.’

‘It had a happy ending though,’

‘Yes, everyone was glad when it was over. Unfortunately his talents were wasted on lame movies in roles that require less finesse than he’s capable of. This even happened in the debut show of a new theatrical season.’

‘Who are they to stone the first cast?’

‘Only the leading influential reviewers who analyse and interpret dramatic works.

They can make or break a production.’

‘Some critics deserve nothing but our pity. To be so close to art and yet to contribute absolutely so little whatsoever towards it.’

‘It’s like being a eunuch at an orgy, ’said Sir John, ‘something for the pleasure of Caligula.’ Little did we know that one day he himself would end up in the same bind. He would be the only person fully dressed at the orgy put on by the cinematic Caligula.

‘How perturbed was Richard by this lack of approbation?’

‘He would cry in mock outrage, ‘Infamy! Infamy! They’ve all got it in for me!’ Actually, to him any such criticism was like water off a duck’s back. He wrote to one critic. ‘I am sitting in the little boys’ room, ‘I have your review in front of me. Soon it will be behind me.’

He received a note from the critic defending his opinion. Richard told me, ‘I would rather have received a suicide note.’

‘But there were some real turkeys, weren’t there.’

‘Some real stinkers. His Hollywood roles throughout the 1950s did not live up to the early promise of his debut. I do worry about him a lot. I’ve warned him of what was said about Hamlet, one of his most famous roles, ‘what a falling-off was there.’

‘What was he like in that role last year? Your production ran for a long time. He can’t have fallen short of the mark.’

‘This welsh rarebit’s Dane is everything Hamlet should be: virile, impassioned, needling, manic depressive, damaged. Pacing the stage, he growled, whimpered, played with his incomparable voice, it’s unexpected rhythms, the way a musician plays with an instrument while tuning it. He made great use of cynical little laughs, tone and emphasis and body language, and sometimes managed to cut up the audience with his creative interpretation rather than anything Shakespeare wrote. No-one has ever depicted the soul in torment like Rich. His mood swings need to be seen to be believed, and are fair convincing as they hammer at a central dramatic issue here — is Hamlet truly mad?’

‘What about his latest film, ‘The Spy Who came In From The Cold’. How does he look here as Alec Leamas?’

‘He looks terrible, but it’s in the service of an performance that sets him apart. Back to brooding, stripped of his ripe theatricality, booming voice and superstar glamour, he plays the role of the apparently burned out British spy superbly. He speaks in monosyllables dispensing with grand speeches or passionate explosions of emotion. His back is to the camera in most of the first scene.

‘So once again as in ‘Becket’, ‘The Night of the Iguana’, and ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’, I said, ‘he’s opted for a restrained approach, emphasizing the inner anguish of the character over emphatic external vocal and physical gestures.’

‘Rich lets us see the pain in Leamas’s dead eyes, the hopelessness in his mopey movements and facial expressions, and the emotional numbness in his guarded, muted reactions. His expressions of irony, pride, disdain, and fright do something rare in a spy movie: they give the film a complicated consciousness.’

‘In the role he gets to put away a good deal of whisky as well, I hear.’

‘’Rich’ knows that certain kinds of drunks enjoy playing rough and acting the alpha male, so it’s hard to know when Leamas is putting everyone on, or where the put-on ends and the real Leamas begins.’

‘I look forward to it’s coming release. What’s next in the pipeline for you, Sir John?’

‘I’m playing the part of Julian in Edward Albee’s willfully obscure Tiny Alice.’

‘That’s good hearing’, I said. ‘And have you encountered any up and coming Hamlets in the making?

Yes, Robert Vaughan, the cleft-chinned star of the TV spy series The Man From

’

’

Another Scorpio like Wilkes Booth who played the Prince of Denmark.’

‘Booth, the assassin of Lincoln?

Yes, after playing the role of Brutus, one of Julius Caesar’s assassins, he became obsessed with the assassination of a real leader.

‘And Robert Vaughn in turn would become obsessed with the same act. Except he mourned the assassination of JFK, one of Lincoln’s successors.’

‘It’s strange how history and theatre overlap, isn’t it. Now Robert’s mother encouraged him to act, teaching him to recite the “To be or not to be” soliloquy when he was five. She had young Robert perform the soliloquy for John Barrymore. Barrymore’s Hamlet stands as a high-water mark of Shakespearean interpretation during the inter-war period.

A dedicated Shakespeare buff, Robert has turned down thousands of dollars of paid work to perform the Great Dane free at the Pasadena Playhouse.

He works in the commercial world to finance his art.’

As we were talking. a storm started to brew outside .

Don’t worry, Sir John. these torrential Sydney downpours don’t last long. It shouldn’t bother you.’

‘Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks!’, he intoned, Rage! blow!

You cataracts and hurricanes, spout.’

‘You’ve got your brolly to keep the water out. Say, what’s the significance of the green umbrella?’

‘In the theatre, it’s a talisman. It started when it was used by an actor as a prop, which helped him look and move like the character he was playing.’

‘I see. A personal object can be a lucky charm for the bearer, though not always for those around. You can’t help notice it sometimes.

‘It’s like the Green Room, that traditional space in a theatre that functions as a waiting room and lounge for performers The outsider would not be aware of it’s purpose but it typically has upholstered chairs and sofas. We wait there before, during, and after a performance or show when we are not engaged on stage.’

‘I can just see you there in the midst of your fellow thespians gripping your green brolly.

I’ll tell you what always catches my eye-short people with umbrellas. Does carrying one work for you?’

‘Most assuredly. It frees up my mind for more important thoughts to crystallise. Like many people, I’m always losing my brolly. Unlike most, I never have to waste time thinking about them and replacing them. Do you have any special way for bringing luck?’

I have a a way to prevent bad luck. To think positive thoughts I throw salt over my shoulder.’

‘I’m sure it gives you better luck than anybody who happens to be behind you. I must remove myself now.’

‘Odds bodkins, I must away now too,’ I said.

As I was leaving, he said: ‘Fare thee well, dear fellow and best wishes.’

I replied, ‘Prithee, Sir John, put your quill where your mouth is.’

To which he graciously accorded.

It has been said that you should never try to meet your heroes, lest they be found to have feet of clay.In meeting me I found flat footed Johnny to have handled himself rather well.

Not like some ambitious and opportunistic people who use others to fulfill their needs.

As John was leaving, I saw him pass by the corner table to greet the young actor.

‘Hello Peter,’ he said putting his hand on his shoulder.

‘Not now Johnny. Can’t you see I’m with someone.’

As Happy as Larry

“Most people put acting behind them when they reach puberty and very often long before. But some of us leap the barrier of self-consciousness and spend the rest of our lives acting out the dreams of others”.

Laurence Olivier.

One of the most eminent artists paying tribute to Chaplin on his death was Laurence Olivier. I would have liked the same mark of respect. My heart sank at first when I saw the first words Larry had written to me. “I can’t tell you how very touched I was by your kind letter …………”

Why couldn’t he? Was he indecisive, lost for words, this consummate actor who won an Academy Award for his performance in ‘Hamlet’? Did he have actors block or RSI? Was he troubled about something? Was he putting on an act? His wife had joked, ‘Oh, Larry’s acting all the time’. After all, it was he who had written in his prologue to ‘On Acting’, ‘Scratch an actor, and underneath you will find another actor’.

Or had Joan, aware how he’d get caught up with strangers, forbidden him to tell me?

Reading further I was relieved when he said how grateful he was for my thoughtfulness.

He was delighted that I enjoyed his work. I had voted him the highest honours.

‘Good show’ I told him, ‘I consider to be screen classics your film versions of Shakespeare’s Henry V,

Hamlet,

and Richard III .

You have brought a greater familiarity of the Bard’s characters to a wide range of cinema goers.’

Like for many young people, it was through his tireless devotion to getting the plays filmed and the vigour of his own performances that I got got my first glimpse of the histrionic malevolence of Richard III.

Likewise the brooding intensity of Hamlet.

I congratulated him for the fresh innovative insight he brought to the character of Hamlet, the role he was offered in 1937. Gielgud’s greatest acolyte had become fascinated with the idea of adapting Freudian psychology to his character. He believed that by providing such amazing portrayals of humans being human, Shakespeare revealed many conscious and unconscious facets of the mind.

Doing away with the flowing phrasing and artificial pretences of previous Shakespearean performances, Olivier invented a new staccato rhythm to reflect the psychological torment of the character.

Watching the film, I responded enthusiastically to his electrifying portrait of the doomed prince. The tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.

He would bring this psychological intensity to bear upon his performance in subsequent films.

This acting animal was one of Cecil Beaton’s favourite subjects.

I praised him for having taken on new roles. He drew the curtain on his romantic screen persona in in Osborne’s ‘The Entertainer’.

This introduced Olivier the character actor in the role of Archie Rice, the seedy pathetic vaudevillian.

Hats off to Larry.

‘The Presumptive Next Laurence Olivier’

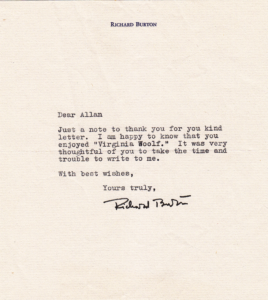

I told Richard Burton the talent with which he was so abundantly blessed shone through in ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf’. It was emitted undoubtedly through his fiery collaboration with Elizabeth, the loving pair having been snapped together by Cecil Beaton.

I told him he had brought out the furtive canniness of George the professor, exposing the limits of others while not rising above his own.

Unfortunately the alcohol with which he was so abundantly pissed had gone through his system and couldn’t be shaken off.

As in ‘Who’s Afraid—-‘, alcohol was an ever-present theme in Richard’s life.

It’s consumed throughout the two-hander, and the narrative is often punctuated by the character’s glasses being refilled. They begin a little tipsy and keep drinking until dawn. Some seem to have real sobriety problems while others drink just to avoid the horrible tensions of the evening. Their lips are loosened as they drink more and more, until Honey is on the bathroom floor and George and Martha grow increasingly harsh towards one another and say ever crueller and more revealing things. Alcohol serves to strip away the false fronts that they might otherwise use to mask and hide their dysfunctions. Being drunk is just another illusion, another way to avoid the uncomfortable truths of their lives.

A cross between Dylan Thomas and an ancient warrior king, Richard’s personal boozing – which was on the heroic scale – appeared as something that the Fates compelled him to indulge in. It was simply part of his nature, the excess the Celts like to claim as uniquely theirs, releasing poetry and song, fortifying for battle, reminding you of the brevity of life, numbing you against its grief. Richard had started to drink beer by the time he was twelve, in imitation of his father and other miners. There were times when, under doctor’s orders or on some personal caprice, he stopped, but he had no time for doctors and was helpless with addiction.

Then again, without the alcohol, would Richard have been able to bring so much pathos and weather-beaten intensity to his roles in films like The Night Of The Iguana , The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf? Partially, because of that magnificent voice and partially because of his gravitas, he excelled at playing kings and generals on screen. All his experience starring in Shakespeare productions at the Old Vic obviously helped too.

Where he was at his very best as a screen actor, was as anti-heroes: defrocked priests, spies or unhappy husbands. He was at his best when playing defeated. He was peerless as priests going to seed in Graham Greene and Tennessee Williams adaptations. He brought an unlikely majesty and lyricism to characters who would have been simply seedy and pathetic if played by other actors.

The First Lady.

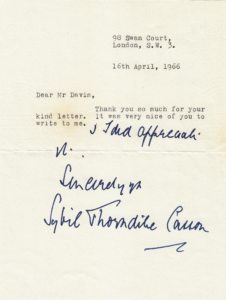

Forever associated with the role of St Joan is Sybil Thorndike, the most majestic of the English Actors. This august First Lady of the English theatre thanked me for my nice kind thoughts.

She paid personal attention to those who admired her work. She could reportedly sweep into a room and make everyone believe they were the one she’d come to see. I saw her successes as embracing virtually all the classical roles for women. Her name conjures up a wealth of wonderful images.

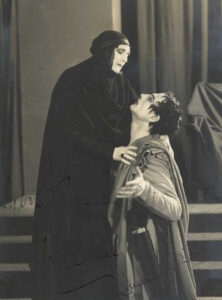

She played Emilia alongside Paul Robeson, the first black to play the role of Othello with a white supporting cast. They can be seen below busily rehearsing.

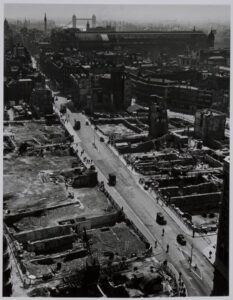

In 1942 Sybil delivered a speech at the Pageant of Saint Paul’s Steps, intended as a morale-boosting patriotic spectacle.

The damage done to the bombed area surrounding St. Paul’s could be seen from the top of the cathedral.

Sybil posed for a portrait for Vanity Fair by Cecil Beaton in 1934 and was sketched by Norman Hartnell with great verisimilitude. This old stager brought fresh life into ‘The Prince and the Showgirl” directed by Olivier in 1957 and starring Marilyn Monroe. She played the role of the Dowager Queen.

Together with Laurence Olivier they hit the peak of their acting careers in Oedipus Rex.

She worked with Olivier in Shakespearean productions. Olivier played the military hero Coriolanus into whom his fierce mother played by Sybil had channelled her ambition . Of this intense relationship Shakespeare wrote, “There’s no man in the world more bound to [his] mother.” Here Coriolanus cries out to her, ‘ O mother, mother! What have you done?…Were you in my stead, would you have heard?”

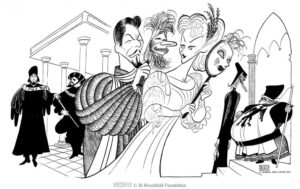

George Bernard Shaw wrote ‘St Joan’, one of the most challenging parts an actress can play, with his great friend Sybil in mind. Sybil was the first to tackle this now famous role on the London stage. With her husband, Lewis Casson, directing her under Shaw’s instruction, they worked through the script with the celebrated playwright.

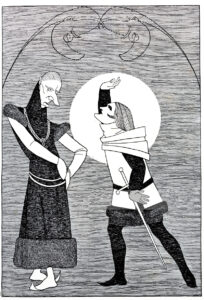

Here under a celestial image of Shaw. she is depicted entreating the heir to the French throne to take up the crown.

She concurred with Shaw’s interpretation of the heroine. She saw Joan not as a sweet country girl, or as Sybil described her ‘a holy bob face’, but as a tough revolutionary.

This representation was of greater appeal to the politically active Sybil.

Sybil had a great sense of humour. Trained in her youth as a concert pianist, she turned to the stage when a medical problem with her hands ruled out a musical career. When asked by her pianist accompanist if she could still play at all, she replied, ‘My fingers are like lightning? They rarely strike the same place twice.’

On the announcement in 1970 that she had been given the royal title ‘Companion of Honour’, she received a telegram from Olivier declaring “I can’t imagine the Queen having a nicer companion”.

The Little Tramp.

“Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up,

but a comedy in long-shot.”

–Charlie Chaplin

Chaplin would have appreciated refuge from the mean streets of Victorian London. Homelessness was integral to his childhood. Before refining his instincts with the sharp intelligence of the artist, he spent time as a ragamuffin Cockney lad in London’s slums living and foraging on the street.

His world was one of bookies’ runners working the street corners, milkmen collecting bets as a sideline, and rag and bone men in horse-drawn carts. It was the weekly wash at the public baths, sugar sandwiches for tea, gas lit streets and smog so thick you could barely see where you were going. Charlie was familiar with the sight of families of tenants and squatters sitting on their belongings heaped in the morning drizzle on the pavement after being evicted.

People on their way to work gazing and buses slowing down to look at the grim sight. This left its mark on his character. He took the mighty down from their seats, stuck pins in the self-inflated and sent the rich away. He expressed his kinship instead with the poor, the hungry and the downtrodden.

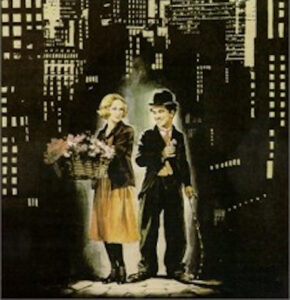

He developed these themes of class distinctions and poverty in the classic ‘City Lights’.

“City Lights” comes the closest to representing all the different notes of his genius. It could be argued that this is his finest film. It brought forth a new level of lyrical romanticism that had not appeared in Chaplin’s earlier works. It is a showcase of Charlie Chaplin as the complete auteur. It contains the leisurely and character based slapstick, the pathos, the graceful pantomime, the effortless physical coordination, the melodrama, the bawdiness, the grace, and, of course, the Little Tramp–the universal figure said, at one time, to be the most famous image on earth, recognized in every culture, perhaps the most recognized until Mickey Mouse– who Walt Disney said was partially inspired by the Tramp — came along.

The film moves with an ease and grace which has the right balance between naturalism and exaggeration. It contains some of Chaplin’s great comic sequences with every scene loaded with ingenious gags. It begins with the unveiling of a civic monument. All of the city’s dignitaries are present – pompous, self-important and full of self-grandiose. The visual shorthand shows us there is a pecking order and that everyone has their place. The Mayor, elected councillors and the police are elevated up high, while ordinary city folk are watching events from beyond.

The monument is unveiled, revealing the tramp fast asleep – an outsider – and certainly not invited to this most important of civic celebrations.

To him, the veiled monument was simply a dry place to spend the night, and as such, this was probably as good as life got for the little man. The Mayor, the police and the dignitaries are all aghast at such disrespect. Of course, the cinema audience and I will have long adopted the little tramp character as their friend and would be interpreting proceedings with very different feelings.

Every following scene is inspired.

There’s a great bit where the Tramp accidentally swallows a whistle and thereafter can’t stop emitting whistle sounds.

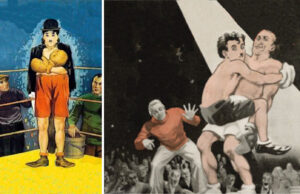

The boxing sequence is one of the most amazing, with Chaplin, a referee, and a prizefighter, all moving around the ring in an expertly choreographed, flawlessly executed comic ballet. The Tramp uses his nimble footwork to always keep the referee between himself and his opponent.

Then there’s the scene following the unveiling of the new monument when the Tramp is drunk at a nightclub eating spaghetti. As he twirls the pasta onto his fork he also catches pieces of flying streamers hanging from the ceiling.

Instead of stopping when he realizes he’s eating a streamer, the Tramp stands up and continues to chew it up toward the ceiling.

No scene is more inspired than the final moments. It deals with a blind flower girl with whom he has become smitten.

The last sequence, in which the girl is able to see the Tramp for the first time, is one of the great emotionally wrenching scenes of cinema.

It’s a sublime moment of emotional simplicity that wells out of all of the adventures that preceded it.

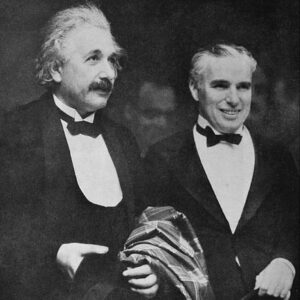

Among all Charlie’s films ‘City Lights’ is my personal favourite as it was his. It was his honour to escort Albert Einstein to the gala premiere.

A memorable exchange from their conversation was shared by the Nobel Prize committee:

“Einstein: ‘What I most admire about your art, is your universality. You don’t say a word, yet the world understands you!’

Chaplin: ‘True. But your glory is even greater! The whole world admires you, even though they don’t understand a word of what you say.'”

Charlie’s own early life was unhappy. With an alcoholic father and psychotic mother, he knew what it was like to feel pain. He spent time in an institution for destitute urchins.

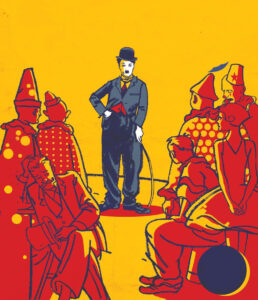

As if to confirm the common belief that comedians are funny to escape their sadness, Chaplin joined a juvenile circus act in his teens. There he developed popular burlesque pieces and was soon the star of the show. This experience provided him with the basis for the last film he made during the silent era. In The Circus Charlie revels in the art of the big top paying tribute to the acrobats and pantomimists who inspired his virtuoso pratfalls.

After being mistaken for a pickpocket, Chaplin’s Tramp flees into the ring of a travelling circus and in two shakes of a lamb’s tail becomes the star of the show. It features a close encounter with a lion and a climactic tightrope walk with a barrelful of monkeys.

As the Little Tramp, he needed no introduction, with his finely pruned toothbrush size moustache, a battered derby hat, a tiny pinched jacket.

His bottom half in huge baggy pants shuffled in a manner that suggested he had never worn a pair of shoes his own size. He wore his size fourteen pair on the wrong feet to keep them from falling off.

The tight upper body was shabby but attempting to look acceptable and proper. This figure of poverty always wore gloves and carried a bamboo cane that seemed to reflect a spirit that bounces back from the most crushing defeats.

Small but pugnacious, he had both virtue and vice. He is a childlike, bumbling but generally good-hearted character. In City Lights he ends up in the boxing ring to raise funds to restore the sight of the blind flower girl. He goes to the blind girl’s humble house to present her with groceries.

While the audience gasped a series of ‘Ooohhs!’, he could be seen scurrying on one leg around corners, clutching his hat to his head while being chased by angry, bewhiskered giants or Keystone Kops.

He was someone who wouldn’t back down. A man who always got up after a knockdown, and usually gave more than he got; a man down on his luck but of indomitable spirit.

In his first films, the Tramp is almost always drunk. That makes him amorous, leading him to make a fool of himself chasing ladies. It makes him aggressive towards other men, who are always his rivals. It makes him fall down a lot, always with his legs at full inversion; and it makes him resentful of authority, willing to buck it, without thinking of consequences. That makes him childlike, which blunts the edge of malice.

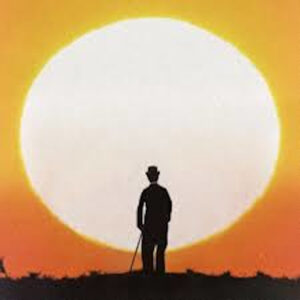

In many of his early silent films the last shot shows him waddling duck legged down life’s highway into the distance.

The essence of the Tramp’s character can be seen in the famous final shot of The Tramp (1915), when Charlie trudges sadly down a country lane, his back to the audience, but then rouses himself. His little dance upon the road is a form of self-definition. He is free. He is essentially alone but he will never truly be lonely because he is infinitely resourceful. . . . He has the will to live in a world that may not be worth living in. The open road is an important conclusion to him; it implies an endless journey, with the Tramp implicitly in the role of Everyman. The ‘little fellow’ was homeless and penniless again, but with hat tilted and rattan cane flourishing, he once more was game for whatever mischief lay around the corner.

Chaplin’s audience tended to project their love for the Tramp onto Chaplin himself and vice-versa, thereby blurring the line between reality and fiction and enhancing the mythical charisma of the Tramp.

Charlie was a a wizard of storytelling who knew how to reach every viewer. There was Charlie and there was everyone else.

He was cinema’s greatest mime. The Tramp was a person for whom body language serves as speech. He exists somehow on a different plane than the other characters; he stands outside their lives and realities, is judged on his appearance, is homeless and without true friends or family, and interacts with the world mostly through his actions. Although he can sometimes be seen to speak, he doesn’t need to.

In The Gold Rush there’s a sequence which charmed me so much,

Chaplin’s character dreams about entertaining Georgia, the dance-hall girl with a couple of forks and dinner rolls.

It wasn’t just another cheap laugh; it showed that you could create a hilarious sequence that also propelled the plot forward. Because this scene was so joyful, it makes reality all the more depressing when the Tramp gets stood up for his dinner date. By being among the first on the silver screen to add a little tragedy to his comedy, Chaplin raised the bar for the art of jokes.

Like the rest of his audience, I saw myself in Charlie’s hapless but always dignified alter-ego. I thanked the clown, as he saw himself, for tickling our funny bone: ‘No one can ever fill your shoes. They could never be sure of the size.’

“It was Bob Hope, of all people, who issued the pithiest, most heartfelt encomium to the man the world still knew as the Tramp: “We were fortunate to have lived in his time.” Despite the obvious polarities in their art- Chaplin’s comedy was physical, Hope’s primarily verbal- and their politics- Chaplin was a socialist, Hope a staunch conservative- they respected each other’s special talents. Hope may have had the gift of gab and Chaplin the gift of mime but they were both meticulous in the art of getting laughs. “I want you to know that you are one of the best timers of comedy I’ve ever seen,” Chaplin told Hope when the two men met in April 1939. Bob was elated to hear such high praise from an artist he’d always worshipped.

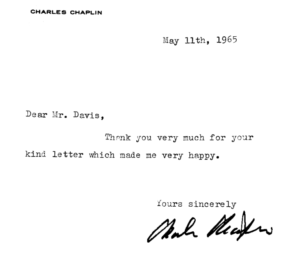

I thanked Charlie for conveying the spirit of the little man in his struggle against overwhelming odds.

I thanked him for his ability to encourage people to think critically.

Charlie said that my kind thoughts for him made him very happy.

His comment to me was very giving of him, coming from someone who had brought happiness even if only fleeting to so many millions in times of war and Depression.

It gave me a terrific boost. Such a nice jester.

What Are We Waiting For?

I was walking with David Evans through a park to swing by a student living in town when we saw two tatty tramps sitting on a bench, trembling, gesticulating and hee-hawing.

‘Shades of Beckett,”David exclaimed, ‘This pair look right out of’ Waiting For Godot”, his existential play . His fictional hapless hobos waiting for a sphinxlike someone who consistently fails to turn up, are a variation of the one created by Chaplin, a man spoken about in the same breath as him.’

‘Who is Beckett? I asked.

‘He’s a very influential modernist writer.

He’s associated with the direction in dramatic literature referred to ‘as the theatre of the absurd’. It emerged in Paris during the late 1940s and early 1950s. The playwrights loosely grouped under this label endeavour to convey their sense of bewilderment, anxiety and wonder in the face of an inexplicable universe. In this schema it is the innermost states of mind- dreams, nightmares and fantasy- that the dramaturge aims to capture rather than the outward appearance of reality.

It sounds very minimalist, ’I commented, considering the scene in front of us. ’

‘It is that. There’s a scene in ‘Waiting For Godot’ consisting purely of a scrawny tree where two down-and-outs await the advent of the mysterious Godot who will somehow transform the future but who never comes. They and the odd bods they meet while waiting, are real people in real recognizable situations. Likewise, our two friends here are living out their own dreams, waiting for something to happen.’

‘The hair of the dog,’ I suggested, casting my mind back to the winos who tottered into our family store. ‘They’re waiting for the bottle shop to open, to bolt down some cheap red ned.’

‘The breakfast of champions. We can’t hear what they’re saying. What they’re saying is beyond our ken, but at the same time we can begin to understand their relationship. They know what they’re saying. They’re talking about things and feeling things. We’ve got to to work out what lies behind the words.’

I could manage to hear some of what was going down between them. One was feverishly cramming his face with grapes. His mate said ‘Jimmy, get a grip on yourself. You have to wait.’

Jimmy replied, shaking like a leaf: ‘I can’t wait. I’m tired and thirsty. I must have wine.’

His mate said, ‘I’m tired and thirsty, too. I must have diabetes.’

Jimmy said, ‘Time is a waste of life and life is a waste of time. Let me have the time of my life and get wasted all the time.’

‘Life can be very hard.’

‘I think sometimes it would be better not to have been born at all.’

‘True, but how many men are that lucky.Maybe one in ten thousand.’

‘Jimmy, do you know what’s going on?’

‘Not only do I not know what’s going on, I wouldn’t know what to do about it if I did.’

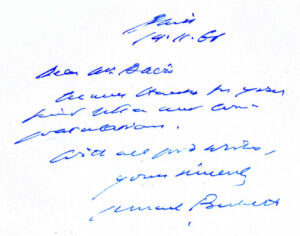

I did my best to work out what lay behind Beckett’s words, dissecting his play to the best of my ability, seeing it on different levels. In a personal panegyric to Sam, I told him he had done his job, creating a work that can be experienced at different levels. ’ He thanked me for my kind thoughts.

‘What were your comments about the nature of his play?’ asked David.

‘I told him it is on one level a deep exploration of human existence, on another a knockabout comedy, at times dark and mysterious, at others uproariously funny.’

‘How did you go reading it?’

‘It demands great concentration finding out who its dramatis personae are, what they want, why they’re there. Production wise, it’s not destined to be your obvious blockbuster. The first read-through I found it quite daunting, so huge, it simply encompasses all of human life no less. There’s more to it after you consider it. Some find its plotline deep and baffling, one of the most complex challenging plays in the English language with its rhythms, syntax and vocabulary. While for some it reveals much about the human condition itself, for others it is utterly impenetrable. It was virtually booed off the stage when first performed a decade ago. Compared to Beckett, Shakespeare’s a walk in the park.

‘There’s actually nothing in the play you can’t understand, ’I said. ‘The language is perfectly understandable. Sometimes people talk bilge. You’ve only got to listen carefully to yourself yabbering to know that that’s very human.’

‘Scoff away, me Hearties’

In the soap opera ‘Desperate Housewives’ the dentist Orson Hodge asks his wife Bree after a meal with his pesky mother (with full servings of caustic zingers and verbal sniping) “How many more Edward Albee dinners do you want to sit through”? Hodge was alluding to that found in Albee’s first three act play ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf’. This was a scalding razor sharp study of a marriage not so much frayed as eviscerated.

It presents an unforgettable, all-night drinking bout in which a burnt out, middle-aged college professor and his fat, foul mouthed, braying wife verbally lacerate each other, drawing a golden boy biologist and his ditzy, mousy spouse into their sexual parlour game. In this tightly wound, painful psychological duel, all their illusions are stripped away, leaving the viewer emotionally strung out.

Albee was one of the writers outside France who showed the influence of the theatre of the absurd. His works are often considered frank examinations of the modern condition. He was a friend of Aaron Copland.

They travelled together to and from the inter American symposium. As a sign of their standing in the U.S. arts, they and others were addressed by President Kennedy.

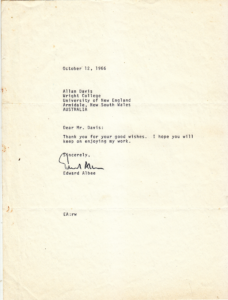

Edward hoped that I would keep on enjoying his work. I asked David if he would like to know what I had said to him. ‘Go ahead’, he replied.

‘I told him I find them amusing with their witty yet whiplash dialogue. I told him he had achieved a careful balancing of a comic style with a tragic undercurrent brilliantly.

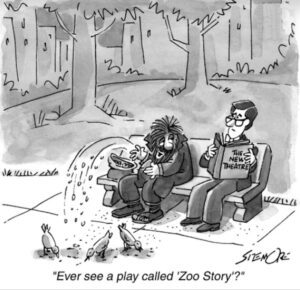

Zoo Story, a short ominous play involving two men who meet on a park bench is about how the failure of communication leads to violence.

The Meaning of Life.

I think I am, therefore, I am… I think.

George Carlin

Existentialist thinkers argue that humanity has to resign itself to recognizing that since a fully satisfying rational explanation of the universe is beyond our reach, the world must ultimately be seen as absurd. While I believe that the universe is a chance event, I believe that through science we are always approaching a more satisfying rational explanation for it – although it is an elusive quest, I believe existence is as meaningful as you make it.

The existentialist’s ability to portray the inner world should complement this knowledge rather than compete with it. Subjectively I feel very much like Beckett’s woman up to her neck in it, but objectively I know that death is a necessary event.

Long Live the King!

My extra-curricular pursuit was that of orchestral music and the musical ensembles that create it, introducing me to more families of instruments, strings and woodwind – and such members as the saxophone, to create a much richer sound. I was particularly interested in how the idiom of jazz had influenced such music.

Dropping by the band hall during my vacation I fielded questions from Iven Laing and John Hinton as to how my musical study was progressing.

“I’ve been getting good marks”, I reported. “‘Professor’ Goodman found my enthusiasm as wonderful as I found both his ‘hot low-down’ sound and his more serious efforts.”

Such as Bernstein’s ‘Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs’ which he premiered.

On hearing of this exchange, John, his faithful cornet at hand teased, ‘Sounds like a ‘Mutual Admiration Society’ and blowing, tootled out the opening lines of this popular tune.

‘He wasn’t short of admirers, was he John?’

‘At a time when Swing Jazz was the most popular music, lovers of his sound came from far and wide to hear his band play.’

‘No one missed out. To make sure of this he toured to many places.’

Wherever the biggest celebrities gathered to graze and chat, the Pied Piper of Manhattan was likely to be there and attract their ears.’

‘What did you say to him? ‘asked John.

‘I told Benny his music was ‘a real belter’. Your sense of form is your gift for weaving a succession of phrases into a single entity. Your lilting sound and its accompanying jitterbug with its fast, bouncy movements quickens my pulse as it did yours and my father’s generation, ready to shrug off the Depression and dance.

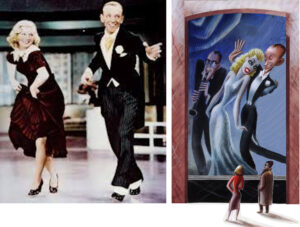

I had in mind Benny’s orchestra backing the incredible Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Their timeless steps were set to the classic “Sing, Sing, Sing” with it’s driving beat. I regarded this routine as a masterpiece of movement.‘

Congratulations for having hosted Jazz’s ‘coming out’ party. I hardly know how to thank you. You helped the Russians shake their blues away, unhappy news away.”

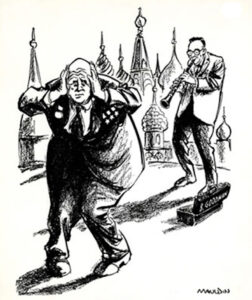

In 1962 his orchestra was the first jazz band to tour the Soviet Union since the 1920’s.

He discussed his music with the Chairman of the Party and his entourage.

However Nikita Khrushchev didn’t swing, according to Benny.

Benny appreciated my kindness and looks forward to visiting my ‘wonderful country’ and meeting me’.

‘What a buzz that would be,’ said John ‘What would you say and do in that eventuality?’

‘I’m your man. I’m taking you on a tour of the Opera House site’, I said without hesitation, having considered this the logical choice.

The Dean of American Composers

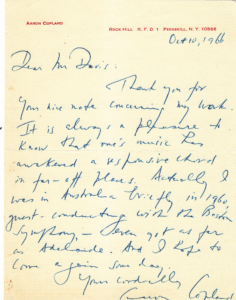

‘I’ve also received favourable notice from ‘The Dean’, Aaron Copland,’ I went on.

‘I thanked him for opening new musical horizons to me. I’m reading his introductory book ‘What to Listen for in Music’. I thanked this American composer, noted for his great rhythmic zip and zing,

for his important contribution to music. He wrote in many styles and forms. Copland wrote a series of film scores.

‘I remember now’, said John. ‘“The Heiress”. He received an academy award for this.’

‘He wrote The ‘Clarinet Concerto’ for Benny Goodman’, I went on.

He incorporated jazz rhythms into symphonic music. His ‘Fanfare for the Common Man’ is one of the most recognizable pieces of 20th Century American classical music. This paean to Joe Blow has been used to open many Democratic National Conventions.’

A couple of years later I would imagine its strains filling the air at the 1968 convention in Chicago while the police were giving anti-war demonstrators in the streets outside a good going over, tear-gassing and pepper spraying delegates and passers-by into the bargain.

‘He incorporated folk music into his compositions, particularly folk songs of the American West. His ballet scores such as ‘Billy the Kid’, ‘Appalachian Spring’ and ‘Rodeo’, draw on this source.’

‘These’d go down a treat with the local hayseeds’, laughed John. ‘ ‘As it is they don’t get ballerinas. One of the local farmhands asked me, ‘What’s with these sheilas dancing round on their tippy toes. Can’t they just get taller women?’ I can just see some of our beefy cattlemen wincing at the idea of arty farty farmhands prancing and mincing in tutus and satin riding boots.’

‘I know what you mean John, but. it’s nothing like that. Set amongst simple pioneering people like ours who crossed the sprawling plains in wagons, these are rugged works, virile and muscular, rough, tough and full of action. Like Billy The Kid who terrorized the West for two decades after the Civil War. While Appalachian Spring is gentle and evocative ‘Rodeo’ is in parts very fast with dash, no holds barred, like roping and riding a bucking bronco. In it cowhands show off the skills of their trade, with vicious syncopations and whiplash percussion reflecting a rodeo’s violent thrills and spills. It provides a meeting place for prospective mates and unattached females. The cowboys and their girls pair off, shuffle and smooch. Hey diddle diddle. Leading on to the famous fiddle scratching, knee clapping, foot-stompin’ Hoe-Down.’

It’s red-bloodedness was not lost down in the stockyards. In the early and mid 1980s the Hoe Down from ‘Rodeo’ would be used by the U. S. National Cattlemen’s Association as background music for its advertising campaign: ‘Beef … it’s what for dinner’. I would imagine herds of cattle stampeding for cover upon hearing the strains of ‘Hoe Down’ from a human’s radio.

I wondered about the risks involved in performing ‘Billy the Kid’ which involved a gunshot at the end.

My mind was put to rest when Iven Laing told me the sound was produced by slapping together loudly the two boards of a clapper.

‘Any others in your high society?’, asked Iven.

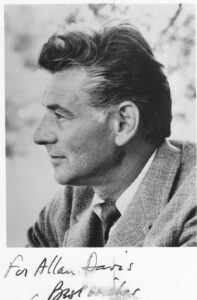

‘‘The Maestro sent me his best wishes.

He took time off his busy multi tasking schedule writing, typing, phoning and composing to reply.

I had told Bernstein he was a real lollapalooza. He was very skilled on his television programs at discussing music clearly and vividly so that he could be understood by people such as me with little musical knowledge.

He could make the most rigorous elements of classical music an adventure in which I could take part.’

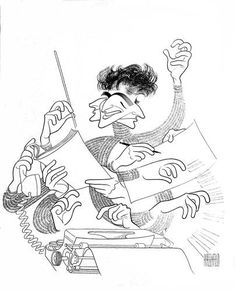

Commanding the attention of the observer, a favourite subject of many an artist, he was always at the centre of things.

By design, orchestras follow a plan, performing music predetermined by specific scores and conducted as such. Improvisation doesn’t typically enter into the equation, unless you’re Leonard Bernstein.

He has internalized the elements of music so completely that he can deal with the particulars of any style he’s involved with, and compose, interpret, or improvise freely in any musical situation.

‘Whatever he takes on,’ said Iven, he does with enthusiasm,’ said Iven. ‘He jumps in with both feet’.

‘And He’s very flamboyant, the perfect counterpoint to his quieter, more thoughtful friend, Copland. Yet they’ve collaborated a lot, I believe.’

‘They’re like peas in a pod’, I replied, covering my index finger with the middle one.

‘Indeed it was Copland’s cat from which he picked up his allergy. Not that this mattered. Love me, love my cat. Bernstein generously helped and secured his friend’s enormous and lasting popularity and influenced his composition greatly. Considered the best conductor of Copland’s works, his favourite is the Piano Variations. He plays it so often he’s come to regard it as his own trademark piece. Like Copland’s his music is infused with jazz and other popular idioms of America . Leonard looks on Copland as on his Biblical namesake, the seer Aaron, who communicates the nub of traditional culture to a new generation through contemporary language.’

‘How does he achieve this?’ asked Iven.

‘Through his-what some call- his ‘long hair’ compositions’, I answered. ‘such as ‘The Age of Anxiety’ for piano and orchestra. But above all through his popular musicals ‘Wonderful Town’ and ‘On the Town’.

Of course, ‘West Side Story’ is the most compelling of all from a dramatic and musical point of view.

‘Does it justify all the plaudits?’ asked John.

I told him I was mesmerized- from the opening bars of the nervy Prologue to the close of his matchless innovative musical.

‘It has raised the standards by which musicals are judged. That good, it’s the most exciting around. Lenny’s range of musical styles adapts to each scene whether it’s the full rhythmic jazz of “Cool” , the jaunty “I Feel Pretty” or a sentimental ballad like “One Hand, One Heart”. Each song is really something and will stand the test of time. His sharp, edgy, flaring score captures what I imagine is the shrill beat of life in the streets as well as moments of tranquillity and rapture. Occasionally there’s a touch of sardonic humor. What makes it special is its marriage of the classical and the hip.’

’Your’s is yet another rave review,’ said John,’ ‘of this most widely followed musician. He is is known throughout the world .’

‘And who knows, maybe even further.’

‘If my memory serves me well, he wrote the music for ‘On the Waterfront’’, added John.’

‘What do you think of Bernstein as a conductor?’, asked Iven as was expected.

‘He’s a real bottler. I told him that like so many others I’m dazzled by his exuberance and vitality. He bounces up and down, he grins, he grimaces, he thrusts and spasms. The emotional climaxes of the music are reflected on his face. He’s thrilled with excitement one moment, anguished the next. He nods and sways, he sweats, he mouths along with the music. Since he works without a score his inner concentration is unbroken.

As conductor he’s a dynamic presence on the podiums of the world’s leading orchestras. As guide to his players he studies each score carefully and makes adjustments where required.

He compares conducting to the act of sex in which you and a body are breathing together, pulsing together, riding on something like waves which are dictated by the composer. Is this the kind of metaphor you’d use yourself?’

“The way the guys are playing at the moment, I would tend to describe it as ‘rough sex.’”

A Lincoln Portrait

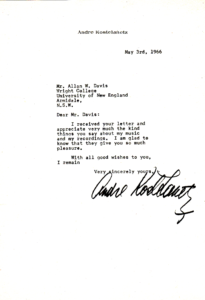

Before becoming a conductor in the USA, Andre Kostelanetz played piano for opera singers in the the Soviet Union.

Navigating his way in the unsubsidised capitalist cultural world proved burdensome at first.

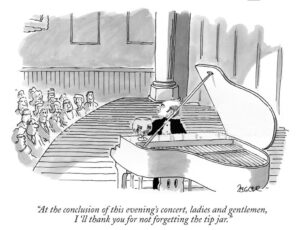

Instead of receiving a tenured income from the state, he had to rely on the generous gratuities of patrons of the arts .

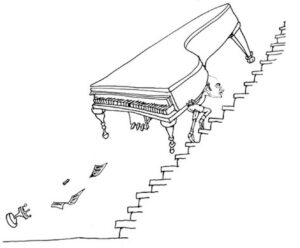

He had to lug a piano around for recitals and piano lessons.

‘The Music Lesson’ lament resonated with him:

‘I really should have studied flute.

Harmonica or chimes,

A clarinet is nice and light,

A fiddle would be fine,

But I had to take piano,

And my student is a brute,

He lives up seven flights of stairs.

Just a baton would be beaut.

With increasing success, Andre was able to afford his own car.

The New World presented novel aural challenges for him. Like Aaron, Andre was faced with having to replicate the sound of a gunshot in his performance of ‘Slaughter on Tenth Avenue’.

Not a man to take unnecessary risks, he called on the Philadelphia police to supply the actual sound.

He was always considering novel ways to win new audiences over to serious music.

I felt he could have best done this by adding a new ending to Joseph Haydn’s ‘Surprise Symphony’. Haydn wrote it to surprise the public with something new.

Generally associated with easy listening, Andre used the wealth derived from his popular performances to conduct more avant garde works such as those of Stravinsky.

An astute businessman, he attempted to solve budget cuts by forsaking rehearsals in the regular concert hall.

While classical music purists fans may have frowned, I loved his version of ‘Carnival of the Animals’.

Andre had the inspired idea of adding poetry to Saint-Saëns’ score. With it’s added set of silly two-line poems that characteristically fracture the English language , they were even funnier coming out of the mouth of Noël Coward in an upper-class British accent. “If you think the elephant preposterous,” he intones, “You’ve probably never seen a rhinos-terous.” And so on.

Noel Coward read Ogden Nash’s “Carnivale of the Animals,” with musical accompaniment by 45 members of the New York Philharmonic led by Andre Kostelanetz on The Ed Sullivan show.

This ‘Music Man’ of the mid-Twentieth Century had the honour of reviewing the music manuscripts of Irving Berlin with the song writer himself while preparing to record his work.

Several of the leading sopranos sang under his baton.

Lily Pons delivered the sweetly lyrical melody ‘Estrellita’ with its potentially ravishing leaps to soft high notes.

Jeanette Macdonald shared his musical mission.

They wanted to introduce opera to a wider audience.

He worked with Beverly Sills, the acclaimed Brooklyn-born coloratura soprano who was more popular with the American public than any opera singer since Enrico Caruso.

He recorded Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue & Concerto in F accompanied by Andre Previn.

Andre Previn played the piano most eloquently.

While the trumpet solos were sublime, Previn gave a top notch performance tickling the ivories.

The ‘Concerto’ has a fluid and smooth flowing sound melding the jazz and romanticism of the day. I loved the gong at the climax of the final movement .

I told Andre I was awarding both he and his namesake the gong for this performance.

.

.

His Carnival Of The Animals voiced by Noel Coward was one of my childhood favourites.

Aaron Copland awakened a responsive chord in Andre Kostelanetz.

Mr Kostelanetz asked him to write a musical portrait about a prominent American of stature.

It wasn’t surprising Aaron chose to write about Abraham Lincoln, America’s beloved and respected president. Lincoln was no reactionary by any means while Aaron’s views were generally progressive . Early in his life he had developed a deep admiration for the works of a group of novelists all socialists whose stories passionately excoriated capitalism’s physical and emotional toll on the average man. He remained a committed opponent of militarism and the Cold War, which he regarded as having been instigated by the United States. He condemned it as ‘almost worse for art than the real thing’. Throw the artist ‘into a mood of suspicion, ill-will, and dread that typifies the cold war attitude and he’ll create nothing’.

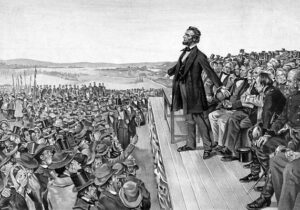

The piece ‘Abraham Lincoln’s Tribute’ was based on speeches and writings of the legendary American president with quotes from his addresses to Congress and the Gettysburg Address.

It expresses movingly Lincoln’s idea of democracy and the struggle for freedom.

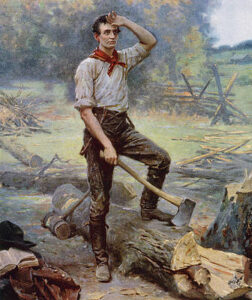

This arose from his roots as a working man splitting fence rails.

This tool becoming the symbol of his identity. Legend has it that in demonstrating his skills to troops, he held an axe at arm’s length for a full minute, demonstrating his strength. The fact that Lincoln had used an axe, as a free labourer, thus became a mighty political statement. He spoke powerfully about how some toil and go without while others enjoy the fruits of this labour. He was referring to the institution of racially based slavery and his abhorrence of this original sin. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy.”

Lincoln drew the important link between democracy and economic freedom. He saw democracy as government of the people, by the people.

Shortly after being elected in 1859 many southern states, fearing the loss of their slave owing privileges, seceded from the Union. Expressing his belief that a house divided against itself cannot stand, he raised an army marking the beginning of the Civil War. Four years of savage fraternal infighting later, the fence rails of the Confederacy were split.

Nobody could any longer be bound in servitude as the property of a slaveholder. Nobody could still be sold on the open market.

The narrative in Lincoln’s Tribute is spoken against a background of majestic music that draws as Copland put it ‘a simple but impressive frame around the words of Lincoln’.

As well as for his contribution to music-his Carnival Of The Animals voiced by Noel Coward was one of my childhood favourites-I thanked Mr Kostelanetz, Lenny’s friend and colleague,

for commissioning the creation of this evocative piece.

Written shortly after Pearl Harbour was blindsided, it helped boost public morale when the nation’s fortunes were at their nadir. It has been narrated by such luminaries as Paul Newman and James Earl Ray.

Written shortly after Pearl Harbour was blindsided, it helped boost public morale when the nation’s fortunes were at their nadir. It has been narrated by such luminaries as Paul Newman and James Earl Ray.

NYFD fireman Kevin Shea, recovering from a broken neck, gave an emotional narration in Carnegie Hall. He saw many of his comrades give their ‘last full measure of devotion’ in the 9/11 attack on New York.