“Conservatives say if you don’t give the rich more money, they will lose their incentive to invest. As for the poor, they tell us they’ve lost all incentive because we’ve given them too much money.”

George Carlin

Not surprisingly my preoccupying interest in the dismal science became that of understanding the factors required for a stable equitable economy. One in which the welfare of all citizens is paramount, structured to satisfy human needs rather than to produce profits.

I learned how fluctuations in prices can lead to instability and uncertainty. How timing is all important when buying and selling.

My study revealed that the best time to buy anything is last year.

It revealed that the best time to sell something can be now.

The prevailing idea in my economic studies was that developed by John Maynard Keynes. His approach to economic policy making was to increase demand for goods and services by government spending and other means. The aim was to guard against the recurrence of the kind of economic depression that had paralysed the world between the wars. There was a feeling that the past had to be acknowledged and a determination that such unemployment and poverty not be repeated.

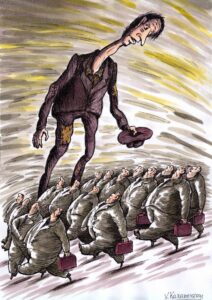

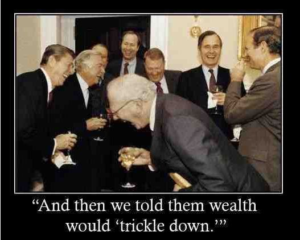

My Economics Professor, Jim Belshaw challenged the efficacy of minimal charitable aid favoured by classical economists. According to the trickle down theory, by keeping workers on subsistence wages, labour costs can be kept low, profits maintained and the benefits pass down to the workforce. John Kenneth Galbraith saw the theory as a less than elegant metaphor that if one feeds the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows. It’s one of those economic policies which favour the wealthy or privileged while being framed as good for the average citizen.

‘Whether we are considering aid to unemployed workers, bankrupt businessmen and farmers pushed to the wall in times of economic downturn, or to those in poor third world countries, it is best that our government support their further training to become sustainable.’ He explained through an old proverb that the ability to work is of greater benefit than a one-off handout: ‘Buy a man a fish and he will eat for a day. If you teach him to catch a fish you do him a good turn. Does anyone here have a differing view of the outcome. ’

‘Teach him how to fish, and he will sit in a boat and drink beer all day, ’was one classical response. ’He’ll have no net income.’

A similar response: ‘You give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. But you teach a man to fish – saved yourself a fish haven’t you?’

Another cynical response: ‘Give a man a gun and he will rob a bank. Give a man a bank and he will rob everyone.’

‘Well, it’s not give a politician a job and they’ll solve the unemployment problem. They’re always trying to convince you that they can if you’ll just give them one.

Professor Belshaw explained to us how agricultural subsidies can help support agricultural enterprises. ‘The government pays them to farmers to supplement their income, manage the supply of agricultural commodities and influence the cost and supply of such commodities.’

‘That reminds me of a New Yorker cartoon,’ I said. ‘There’s an accordion player on a subway platform with a sign next to his cup that reads, “Will not play Lady of Spain, 25 cents”

Alven Hansen, the farmer’s son from South Dakota, remembers his father giving the following account of subsidies. ‘The government will pay certain farmers to not grow corn. Wow, where’s my check? That’d be great.

‘Hey, what do you do for a living?’ I get asked.

‘Well, I don’t grow corn. I get up at the crack of noon, make sure there’s no corn growing. You know we used to not grow tomatoes, but there’s more money in not growing corn.’

Great Leaps- Backwards and Forwards.

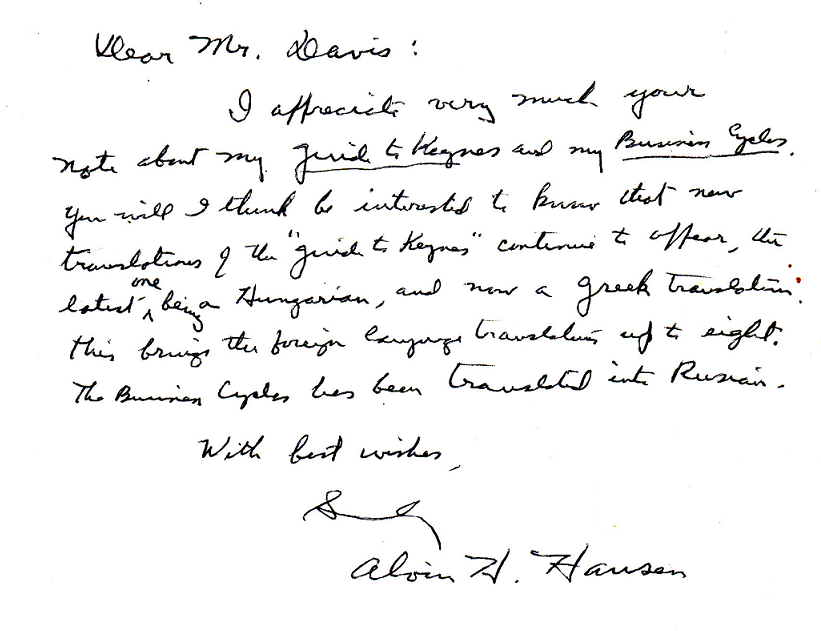

Alvin Hansen from Harvard University wrote one of the most authoritative texts on Keynes. He urged greater government spending for schools, hospitals, roads, housing, slum clearance and power development. He believed, where necessary, there was a place for taking privately-controlled companies, industries, or assets and putting them under the control of the government.

Argentina nationalised its rail industry after WW2.

Even the United States has a long and rich tradition of nationalizing private enterprise itself, especially during times of economic and social crisis. The rail system was nationalised briefly after WW1 and today rail unions and progressives continued to champion the prospect of railroad nationalization.

While I getting my head around these fiscal ideas, Professor Hansen told me that his work ‘Business Cycles’ had been translated into Russian.

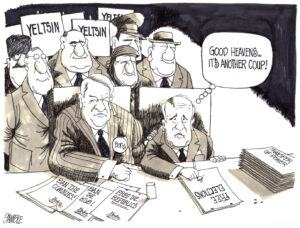

I found this interesting as with all their stopgap measures to solving problems, the Russians through the planned economy had largely been able to avoid the chaotic fluctuations of the market economy. They would well done have studied such ups and downs to understand their fate – their cast-iron stagnant economy bankrupted by the stakes in the arms race being constantly raised, going west cold turkey, joining the triumphalist world capitalist economy as a whips and jingles basket case, on one big ‘downer’. Like Humpty Dumpty it couldn’t be put back together again.

Harold Macmillan had observed wryly that the Russians ‘ may know how to make Sputniks, but they certainly don’t know how to make trousers’. Of course they have always known how to make proper trousers but diverted resources and know how to space technology instead.

Then came Glasnost. It gave everyone the right to complain and accuse. But it didn’t make more trousers, or better ones.

Unable to lick us, their new elite, midwifed by the state, would join us, hoping to be pulled along in the slipstream. Moving to the capitalist right at the speed of light. Rejecting state interventionism, off to the I. M. F. with their begging bowl. Sharing our ‘hit and miss’ cult of the individual, private property, and casino capitalism on steroids, it followed the ‘shock therapy’ prescribed by the neo-liberal witch doctors.

Under it the new State would pursue the globalization agenda pushed by the U.S., which integrated countries with each other. Russia would be at the core of that integration, not only for the export of fuel but also for the export of the wealth stolen from the Soviet state. This was common wealth managed by the state on behalf of the citizenry who owned and worked it.

Managing the country’s resources by the new owners involved twisting and turning around fresh obstacles .

Russia would pursue a policy of uneven development privileging certain areas as the motors of economic development and re-concentrating resources in ‘strategic areas’. The strength of of neglected areas would atrophy.

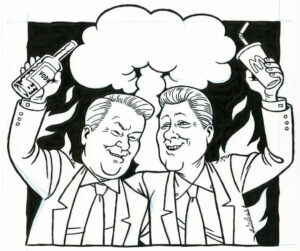

With Clinton standing by his side, a steadfast source of support, Yeltsin and his friend celebrated ‘The Greatest Leap Backwards’.

While the two exchanged hugs, joking with each other, millions of Russians would hit the wall, missing their jobs and their homes, their savings and their common wealth engulfed, gutted and devoured. Those who objected enough could be imprisoned so that prices could be free. In the Wild East precious little would trickle down.

It all gushed up.

The people’s property was effectively auctioned off and gathered up by the oligarchs for their own wealth. Believing tomorrow belongs to them, these kingpin capitalists and other high rollers expropriated the ownership of public capital, getting rich on public share sell-offs and massive bonuses for cost-cutting.

This happened despite warnings over the years to prevent such a counter-revolutionary takeover.

Russia became one big petrol station with a bunch of rusty nukes out back. It’s industries have never recovered from the fall of communism, and its economy is now based overwhelmingly on the export of fossil fuels, with much of the rest made up of energy-dependent mineral resources, such as iron, steel, aluminium and other metals, and some agriculture.

This dependence would enabled the rise of a strongman like Putin, who would gather the kleptocrats under his own control. As gangsters and private armies revealed themselves babushka doll style, rooting about the carcass of the command economy, for many former soviet citizens , including war veterans and babushkas, their quality of life would deteriorate. Like in Britain and the U.S., only worse, massive public disinvestments rendered school accommodation unusable, hospital buildings with walls falling down and public transportation downright dangerous to use. Workers were left straggling, thrown onto growing industrial scrapheaps.

How are the mighty fallen.

Farm workers discovered the land they had lived on and worked for generations had been sold out from underneath them. And like most of the Russian population now confronting the consequences of privatisation, they had no clear idea how this happened or where the money exchanged, if there was any, went.

Debt collectors circling, desperate people bartered their battered housewares in the street to scrape by . Retreating to homes where the electricity flickers on and off and the telephone often goes dead in the middle of a call. Women transported into virtual slavery by prostitution rings involved in human trafficking. Oh bondage up yours!

Little wonder some would turn to the universal suspicion that whatever Now is like, Then was better. They would voice nostalgia for the good old days of Stalin when things worked properly. When a cult came with poisonality.

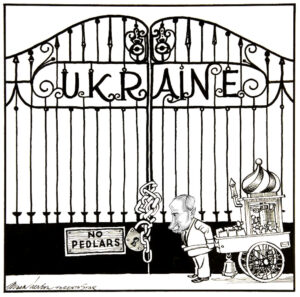

This longing for the past would come back big time with the policy of NATO members vowing to weaken Russia further after it’s invasion of Ukraine. This would be the same approach taken to Germany after WW1 with catastrophic consequences.

Both Russia and the EU have maintained that integration with the EU is incompatible with membership in the Russia-sponsored Eurasian Customs Union. Both blocs have essentially told Ukraine, “You’ve got to make a choice, Ukraine: Either you have a very close and deepening trade relationship with the EU or with Russia, but not both. You can’t have the same depth of trading with both Russia and the EU at the same time.”

Now, the Russians would object to that, because, of course, they have had long-standing relationships with Ukraine, very deep economic relationships.

They have also been deeply cultural and personal.

Russia would push back attempts by the European Union to drag Ukraine away from its orbit.

A Nugget of Wisdom.

Professor Belshaw told us about the unbridled strain of capitalism with respect to the governor of Australia’s central bank – the Reserve Bank. ‘Dr. Coombs warns against any return to the bad old days, that if unchecked it condemns us to recurrent wars and crises. He believes the earth must be nurtured wisely. An ardent supporter of environmental ideas, he’s impressed with the small-scale economic experiments to achieve sustainability in the new Chinese People’s Republic. His visit there in 1961 paved the way for Australia selling wheat to our giant neighbour.’

I became particularly interested in the way in which the monetary system affected economic activity.. I studied more about Dr. Harold Coombs. He thanked me for my kind remarks to him when I was studying Money-the lifeblood of the capitalist system.

His signature was on all of our bank notes. I thanked him for his compassionate approach to people.

A self styled activist and interferer, he saw it as the public servant’s line of duty to protect and develop the interests of society as well as those of the state which employed him and her. His social conscience and commitment were stirred during his years of study in London. He was appalled by conditions created by the Depression in what purported to be a modern industrialized society. He embraced Keynes interventionist, deficit-spending ideas. As a student, he used to dine with Keynes. ‘I am by nature an interferer, ”he once said, ”and I would like to do something about things if I can. There is too much poverty, too much intolerance, too much hatred.’’

During World War II he was director of rationing: the man who cut off the nation’s shirt tails to save cloth. Frugality was a virtue in that time of need. People were urged to make do and mend.

Dr. Coombs believed that rationing should be based on equity and solicitude for each and every individual. He promoted rationing as being concerned with “fair shares”.

Dr. Coombs believed that rationing should be based on equity and solicitude for each and every individual. He promoted rationing as being concerned with “fair shares”.

He was a driving force in encouraging women to work for the war effort. While the men were in the armed forces, there was a significant increase in the number of women employed in factories.

Women provided a new rural workforce.

A former teacher, Dr. Coombs promoted lots of practical, common sense ideas designed to eliminate waste, contribute to the war effort .and raise the standard of living of Australians. “Dig for Victory”, was a publicity campaign urging householders throughout Australia to grow their own vegetables.

A home vegetable garden reduced uncertainty around our food system and access to fresh ingredients. He emphasized the importance of keeping our food chain as close to the source as possible.

His department warned of the effects of overcooking and keeping food hot for extended periods. This leads to loss of vitamins, goodness and taste, all these going up in smoke.

Everyone was urged to do more to reduce food loss and waste or risk an even greater drop in food security and natural resources.

Navy personnel were advised: ‘When you take more than you eat, you cheat your mates in the fleet!’

The mobilisation of natural resources and material for the production and supply of military equipment was a critical component of the war effort. This put a heavy burden on supplies of basic materials like food, shoes, metal, paper, and rubber .

All Australians were asked do their part in supporting the war effort by collecting, saving, conserving, and recycling materials that could be repurposed for military uses.

Like governments of most warring nations, ours implemented salvage drives and had scrap metal, paper, bones, or other waste materials exploited as a supplementary national resource base to back the war economy.

Wasting materials was seen as tantamount to assisting the enemy.

Not wasting food didn’t stop at not wasting just the meat.

People were reminded that bones were needed to make glue for housing and fertilizer for food.

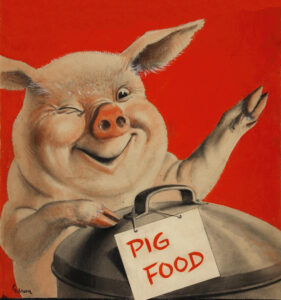

While pigs will eat nearly anything, this doesn’t include bones. Their owners were encouraged to feed them food scraps but carefully. This included uncontaminated fruits, vegetables, bread, grains, dairy, eggs, and vegetable oils.

People were reminded that paper helps to make munitions.

They were reminded that rags were needed for salvage and should be collected for reuse.

Equipment such as drums for storage of latex had to be well maintained.

Dr. Coombs spearheaded a collective response to the need to save energy for the war effort. The message was clear: stop using so much fuel, because it was needed for the fighting troops.

He called on industry to reduce it’s consumption of electricity.

He called on the populace to curb it’s dependence on coal for heating the home.

He urged people to take action to cut consumption of gas and food due to scarcities. Difficult choices had to be made.

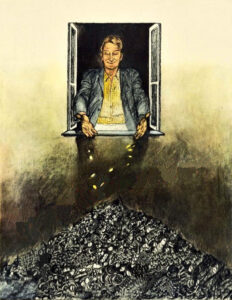

Dr. Coombs advised business and the populace not to spend money frivolously, recklessly, or wastefully. This was simply throwing money out the window.

Dr Coombs or ‘Nugget’ as he was affectionately nicknamed was appointed to a new post of Director-General of post-war reconstruction – charged with promoting ideas designed to make Australia after the war something to live for and fight for. One important task was to successfully restore time expired veterans to civilian life. Appointed as head of the central bank by Ben Chifley, his objectives included controlling creation of credit so that those whose needs and deserts were greatest were those who benefited most, and second controlling credit so that it enhanced the efficiency of the system. During his tenure as central bank governor, from 1948 to 1968, he tended to favour less intervention and greater Government discipline over spending.’

In banking legislation he made good at writing a charter charging the bank specifically with the task of promoting stability of the currency, full employment and the economic prosperity and welfare of the people.

In later life Nugget would despair at the tunnel vision of the modern economist and the lack of idealism in public life, bemoaning the reason of a new, uncaring intelligentsia. The battle of ideas, he said, was being won by an uncaring corporate society without a sense of community obligation.

By intelligentsia,’ he told a seminar on ethics, ‘I mean not those people who have inherited power because of nobility, but those who by good fortune have had access to time to think or to read or to argue; those who have had the benefit of what we used to call small liberal education; those who have inherited the same kinds of obligations as the lords of the manor inherited – the sense that we, too, have an obligation personally to care for others. One of the distressing things to me about what has happened towards the end of my life is… the fact that decisions are made without the kind of study which it is the function of the intelligentsia to provide, that decisions are made without allowing that kind of debate in an independent context.

It distresses me to see how far the corporate society, in addition to taking over the economic culture of the management of resources, seems to have taken over the intelligentsia. … Regrettably, the intelligentsia is becoming increasingly the instrument of the corporate society”.

Supermac.

Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.

Shakespeare Henry IV. Part II

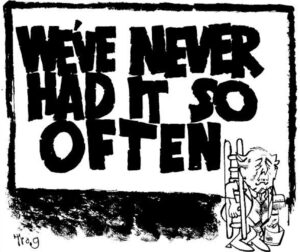

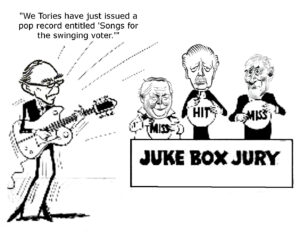

First-hand experience of the horrors of the Depression had led even the conservative Harold Macmillan to advocate Keynesian policies then unpopular in his party. He went to the country successfully in 1959 with the slogan, ‘We are all workers now.’

Before that the war gave him a first taste of contact with working-class men. Being shy and retiring by nature, one who had developed an ‘extreme dislike of doing things in public’, he admired the ease with which they interacted with one another,

A cut above the rest, with sincere notions of noblesse oblige, this member of a patrician family worked at winning over the Conservative Party to accepting the welfare state. ‘The nation cannot afford it,’ complained one hardline Tory. ‘Every time that Labour moves to the left, the decimal point in the budget moves to the right.’ Limiting funds for pensions, family allowances and the national health service would have of course hurt even his party’s middle class rank and file. It could be patronising if not punitive.

His constituency, Stockton-on-Tees was one of many depressed areas where widespread unemployment and hopeless street corner groups of unwanted men haunted Britain for years between the world wars. This unhappy population was like a broken army walking away from a war, cheeks sunken, eyes dead with fatigue. Some carried bags of tools, or shabby cardboard suitcases; some wore the ghosts of city suits; some, when they stopped to rest, carefully removed their shoes and polished them with handfuls of grass. Among them were shaken out carpenters, clerks and engineers. Men who slept out and lived rough as guts, begging as they went and working where they could.

This human waste made a mockery of the ‘land fit for heroes’ that had been promised to soldiers returning from the 1914-18 world war.

An astute statesman Macmillan cultivated a public image that was reassuring, imperturbable, sensible, urbane, slightly aloof, always in control and focussed.

With his Old Etonian tie and Balliol shuffle, he seemed the very model of an Edwardian scholarly gentleman. He saw himself as both a “gownsman” and a “swordsman” and was as accustomed to a pen at the ready as a firearm.

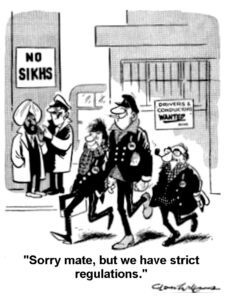

In the immediate aftermath of the racist violence that had erupted in Nottingham and Notting Hill Gate in the 1950’s, he had shown determination in being seen not to give way to racist demands.

He supported the necessity of a mixed economy with some nationalised industries and strong trade unions. He championed a Keynesian strategy of deficit spending to maintain demand and pursuit of corporatist policies to develop the domestic market as the engine of growth. Benefiting from favourable international conditions, he presided over an age of affluence, marked by high—if uneven—growth. He primed the pump so to avoid unemployment.

As minister of housing and local government (1951-54) he triumphantly made good on a Conservative pledge to build 300, 000 new houses a year.

I told him this was the right direction. He appreciated this as well as my solicitous enquiry regarding his health.

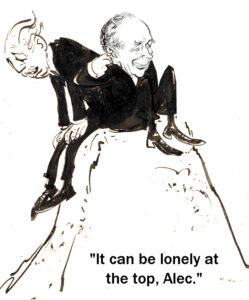

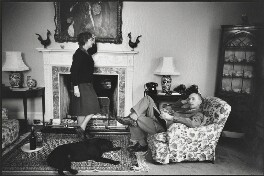

Beneath his mask of clubbability and elegant wit lay great unhappiness. He was all too aware that powerful and successful people often have few friends.

Constantly apprehensive, he suffered appalling ‘black dog’ depressions and could never escape ‘the inside feeling that something awful and unknown was about to happen’.

In political and economic matters success could suddenly fall off the cliff and founder on the rocks.

Such a turn of events certainly did happen to the credibility of his government. The sixties was a decade when attitudes to sex and to the equality of the sexes were severely shaken up.

His Minister for War, turned on by the times, carried on an extramarital affair with a 19-year-old model.

The Profumo Scandal, centred on the Minister’s lies about it, stripped Macmillan naked and forced him into an untenable position.

He could not remember ‘ever having been under such a severe personal strain’.

That is how Churchill referred to Macmillan’s chosen successor. It was suggested that that the member of the House of Lords in the play ‘The Reluctant Peer’ was Alec, and that this was the humorous side of the story of how Lord Douglas-Home came to give up his title to become Prime Minister to Queen Elizabeth. After all it was written by his brother William Douglas Home, seen below beside Alec and facing Sybil Thorndike who played a leading role in the Duchess Theatre production.

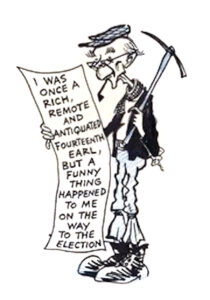

Torn down by the Labour Party as an out-of-touch aristocrat, Alec Douglas-Home came over stiffly in television interviews. He was regarded by many as no more than an armchair politician.

As prime minister, Douglas Home’s demeanour and appearance remained aristocratic and old-fashioned. There were doubts even in the Conservative Party hierarchy about Sir Alec’s ability to personify enterprise, youthfulness, and relevance to contemporary circumstances. Party managers became obsessed with the effect of Sir Alec’s television ‘image’, then a new ingredient in electoral politics.

He had no gifts of imagination or of oratory, and he knew it. In a broadcast he made on the day he became prime minister he said: “No one need expect any stunts from me – merely plain, simple talking.”

Macmillan primed him in how to polish up the opinion people had of him. How to act and look like more one of them.

How to act more like them.

He would have to be seen not as a rich landowner with servants.

He would be seen rather as a servant of the people.

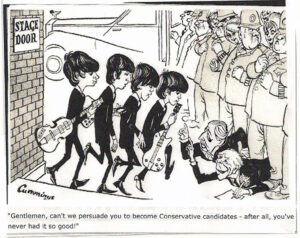

He would have to win over the young to the Conservative Party.

He would have to look more ‘with it’

This makeover wasn’t a walk in the park.

Economics was never his strong point. As a young member, during the period of mass unemployment, he had few economic remedies to offer. The young member for South Lanark had suggested in the Commons that unemployed coal miners and their families might be brought down from Scotland to the London area to work as domestic servants.

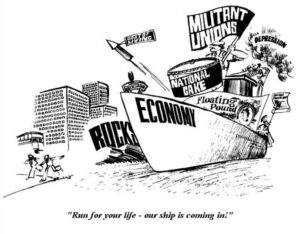

Once in Downing Street, his government had to face the usual increasingly adverse balance of payments and a growing threat to sterling. Sir Alec had no gift for handling such problems, and the Conservatives were naturally not anxious to enter a general election with a program of economic austerity.

Such a program would never daunt Mrs Thatcher. She would head in that direction with savage cutbacks referring to Mr Macmillan belittlingly as a ‘closet socialist’.

She would never openly snipe at this venerated and hallowed father figure of the Conservative Party, of course. That would be left to some Young Tories who saw him as not ruthless enough.

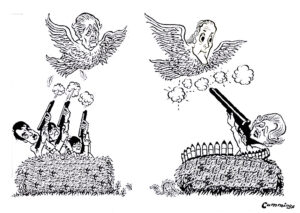

As for Mr. Benn, across the floor in the Parliament, she would view him as well and truly ‘out of it’. She would keep taking pot shots at him herself in Macmillan’s old political hunting grounds.

Off with Her Head!

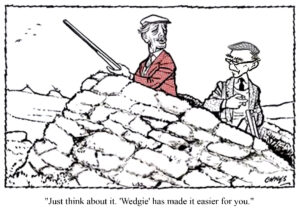

Having been a childhood philatelist, I noticed that on the letter from the double-barrelled Mr. Anthony Wedgewood Benn, as he was formerly known, the Queen’s portrait on the stamp had been scaled down to a pintsized profile in silhouette. The cameo in the corner. A republican, he wanted to permit the introduction of “non-traditional” designs – of landscapes, portraits of composers and so on. He persuaded the Queen to overrule officials who deemed Robert Burns unfit to appear on a stamp. As Postmaster General, scaling up the functions of the Post Office, he had proposed issuing stamps without the Sovereign’s head. He knelt on the floor and spread stamp designs before her very eyes, but this time it met with her private opposition.

He went on to say: ‘If the Queen can reject the advice of a minister on a little thing like a postage stamp, what would happen if she rejected the advice of the prime minister on a major matter? If the Crown personally can reject advice, then, of course, the whole democratic facade turns out to be false.

This protest epitomised what Benn stood for throughout his political life: the massive patronage afforded to a prime minister through the Crown.

Formerly 2nd Viscount Stansgate, who had worn top hat and tails as a public schoolboy, he was as recognisably English as a character out of Anthony Trollope or even PG Wodehouse. Yet he didn’t want anything handed to him on a plate. He fought a vigorous and eventually successful campaign for the right to renounce his peerage and the usual box of tricks. All in order to be eligible to eligible for a seat in the House of Commons. He had successfully contested an election but couldn’t occupy it because of his title. Ironically, his victorious Conservative opponent was himself the heir to a peerage, held by his cousin. Benn said the situation could be most easily resolved if he murdered his opponent’s cousin.

The Clerks in the House of Lords told him to they were very insulted that anybody did not want to be a peer. He said: ‘If I had arrived with a string around my trousers and a choker scarf and said I was a dustman but thought I had a strong claim to be the Earl of Dundee, I think they would have treated me with more respect!’

The press called him “the reluctant peer”. Benn said that was wrong. He took some blood out in a vial and said he did not have blue blood at all, and that he was not a “reluctant peer” but a “persistent commoner”.

The result of his campaign was not foreseen. The law of unintended consequences had kicked in. He paved the way for the Tory grandee, the 14th Earl of Home, who also renounced his peerage.

Charging through the opening, somewhat to the discomfiture of Mr. Benn and other Labour MPs, the Earl would automatically secure the prime ministership. Home at last!

Mr. Benn was in the forefront of the technological revolution of the 1960s. When I read his article [‘The Guardian’ February 1964] in the university library, I had to refrain from shouting ‘Eureka! He’s got it. The Red Sea has parted. This politician understands it. ’ In ‘The Guardian’ February 1964, he denounced the culture of amateurism and an overly narrow specialization at the same time: ‘Both narrow their vision when it should be broadened’. Of the two he saw the cult of specialization as probably becoming the most dangerous: ‘To take a narrow view of human beings is both destructive of the human personality and also unscientific. The interaction of one factor on another cannot be considered by the specialist alone. The urban explosion is a perfect example of the failure to relate industrial development, housing development, road construction and office building, one to another.’

This specialisation and fragmentation would come to mark so many disciplines. I found that this leads to a narrowing of focus, a shallowing of thought, an increased unwillingness to discuss broader issues including the methods and philosophical underpinnings on which various disciplines rest.

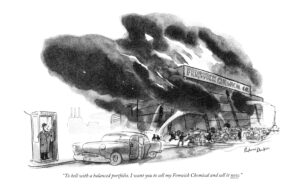

Mr. Benn saw that it ‘may create its own mythology of expertise designed to freeze out those whom it’s elite do not think qualified to comment. Yet it may well be that the most valuable member in society is the innovator who, though not necessarily the best in his field, has so successfully retained his capacity for general thinking that he can make the really important breakthroughs and make the relevant connections. Anything which makes it harder to locate the innovator or makes it harder for him to play his vital role will be a loss for the whole community.’

Taken to its logical conclusion, more and more specialisation means that everyone becomes better and better at less and less and eventually someone will be superb at nothing at all.

As a generalist high school teacher working in the N. S. W. Department of Education with its baleful record of delivering literacy skills and protecting children’s welfare, my ability to convey such skills and concern over children in my charge at risk was totally disregarded by it. Mr. Benn contrasted the revolution he had in mind, based on education and research with human goals, with the traditional one where firstly barricades are built. ‘Ours must begin with the destruction of the barriers that now divide us from one another.’

I gave my encouragement to this boyish enthusiast in his public office. Having increased the functions of the Post Office, the dashing ‘young Lochinvar’ was promoted inside the cabinet in charge of a new ministry that he believed could ‘really change the face of Britain and its prospects for survival.’ This long term belief was fuelled further when Douglas Home’s premiership went up in smoke.

It was Mr. Benn who was given a large part in implementing Harold Wilson’s “white heat of technology” agenda. In 1963, Prime Minister Wilson had delivered a speech to the Labour Party saying that for Britain to prosper it must be forged in the “white heat” of a science and technology revolution. He committed to setting up a Ministry of Technology to lead this with Benn as Minister. The Queen told him: ‘You’ll miss your stamps. ’

Mr. Benn gave voice to a formidable minority in the Labour party wanting to reverse the long deviation from its socialist agenda and to transform the political, economic and social systems through a comprehensive program of nationalization, including financial institutions, welfare provision and unilateral nuclear disarmament. He believed a state possessing such weapons and the means to guard them has insulated a whole part of itself from democratic control.

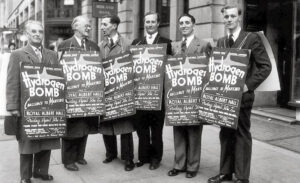

In February 1958, the month of CND’s foundation, Mr. Benn resigned his position as one of Labour’s front bench spokesmen on Defence, stating that he could not, “under any circumstances, support a policy which contemplated the use of atomic weapons in war”.

I encouraged Mr. Benn in this and to help bring about a Race Relations Act. This would be to eliminate racial prejudice in employment of minorities.

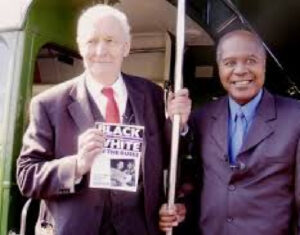

He had given crucial support to the successful Bristol Bus Boycott. This protest at the Bristol Omnibus company’s refusal to employ a black driver would be instrumental in creating the 1968 Act.

I encouraged him to help bring about not just this but also the easing of divorce. I saw these steps forward and discussions over raising the school-leaving age as the progressive capstones of the Wilson administration. I told him, ‘Your blood’s worth bottling’.

I passed on a joke to him: ‘And what rank does your uniform signify?’ asked the old lady of the officer. ‘I am a naval surgeon, madam,’ he replied.

The lady exclaimed in wonderment, ‘Goodness how you doctors specialize these days!’

‘Wedgie’ got back to me promptly.