Angkor What?

During my years in the groves of academe I developed a strong urge to explore what was on The Other Side, leading me on to discover the excitement of foreign places. My vagabond shoes were longing to stray. I was interested in exploring the interplay of East and West that Pearl Buck wrote about. At the end of my sophomore year I did a test run, circumnavigating Tasmania by road.

I started out sleeping on the ground beside the road.My first night out was rough. I heard eery thumping on the ground, presumably from passing kangaroos. A rainstorm soaked me, I woke to find two cows snorting and grunting over me and I took shivering refuge in a damp ditch. That’s when I found out about the virtue of the system of youth hostels.

Being accustomed to hitchhiking between Gunnedah and Armidale frequently, I learned to make a good fist of putting on an appealing face and extending that short opposable finger that enabled man to progress ahead of most of his ape cousins.

To start, I would position myself at the edge of a town giving every passing vehicle the full thumb wagging routine . I looked for petrol stations as they gave anyone driving off the forecourt a good opportunity to see I was a safe bet. ‘Hey, look me over, lend me an ear.’ Close eye contact with the driver helped with the portrayal of a pleading expression which is not difficult after a long wait. This would go some way to instilling a feeling of guilt or generosity in the driver. At the side of the road, with my body directed at the traffic, I’d stick my thumb miles out so drivers could see that’s what I was actually doing. It went best when they were going quite slowly so that they can could get a good look at you. Some drivers looked directly at me and pointed at the ground with their index finger, signalling that they couldn’t give a lift as they were staying local. It was reassuring to get such acknowledgement.

I’d learn lots about the drivers’ lives in the front-seat confessional. Often, they’d often just unload their thoughts, aspirations, fears and regrets really quickly. Some really intimate, full-on details. People just go straight there because they believe they’ll never see you again. You’re like a priest.

My most satisfying discovery was the generosity that people showed to me by sharing their vehicle and offering me hospitality. When drivers smile upon you, the heavens open up from above and you can find yourself taken in, taken home, and for all practical purposes adopted for life. This kindness of strangers sounds like a fantasy to some.

Being able to go anywhere without my own car raised my confidence. One of my early times being picked up after having waited some time that drove this feeling home.

‘Can you give me a lift?’ I asked the lady driver after she pulled over.

‘Sure, you look good enough, the world’s your oyster, jump in,’ she replied, reaffirming David Evan’s booster.

I got on well with the overseas students at Armidale. The Asians were mostly students from Indonesia and what is now Malaysia studying in Australia under the Colombo Plan. In my hall of residence lived Rick Lay, Abbas and Nik Mohamed and Frankie Liew from those places. We shared the ethos of studying seriously hard to keep our place. I certainly couldn’t afford to drop the ball. We chowed down curries and played hockey and table tennis rather than the beer and rugby combination which the brawny Aussie preppies coming from the private schools indulged in. This was more a cultural thing than anything. Of ample girth, from sturdy stock, the Fijians in Wright were in their element with the heavyset jockstrapped ruckmen, tackling and locking horns with the best of them. These human battering rams from the Pacific could chugalug their booze with equal zest. You were excused otherness if you were a great one for rugby.

The Road From Singapore

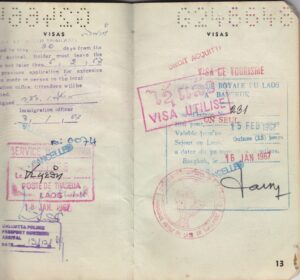

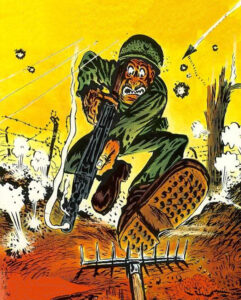

On itchy feet I spent one summer vacation in my penultimate year at UNE as an innocent abroad hitchhiking around South East Asia. Better to follow the hippy trail than the Ho Chi Minh Trail, it’s dark twin. This was uncommon for a young man from rural Australia in the mid 1960s. The romantic soul’s attraction to things exotic may be as irrational as the suspicion of the xenophobe; in either case, the mysterious unknown exerts its reach. For several generations, most Australians had thought about Asia as a threat to scorn, seething with communist agitators ready to extend the Bamboo Curtain south, rather than an attractive travel destination.

One acquaintance from college asked me: ‘Why do you want to go there of all places?’

‘I’m terribly curious to know about life there.’

‘A curious student is a teacher’s delight. A curious tourist can be seen by suspicious locals as a nuisance.’

‘You do it young, or you don’t do it at all.’

‘It’s not too late to back out. You’d better not go alone. It’s safer to stay at home. You can do yourself a great disfavour. You’ll have to keep your wits about you all the time. Backpackers have been known to be slugged, mugged, bugged, slung in the jug, shoved under some rug, given some drug. Some now fertilize the paddy fields. It’s the most violent part of the world.’

‘I hadn’t realized. Thanks heaps for the tip. I’ll mind how I go.’

‘If anything like this happened, you’d never forgive yourself. You can have your passport and traveller’s cheques stolen, or worse disappear. There’s too many ‘ifs’ and ‘buts’. Keep in mind the expression,’ he reminded me, ‘curiosity killed the cat.’

‘I prefer the other one. ’I replied. ‘About a cat having nine lives.’

‘If you end up in trouble,better cut out on the double.’

Before the ’60s most Australians who could afford to travel had only glimpsed Asian landscapes and people through the portholes of the ocean liners that took them to the white cliffs of Dover; a few shellbacks stopped for a night or two in Ceylon and came home with tales of noisy markets, pushy tour guides and the ubiquitous rickshaw ride.

Like the globetrotting local in our shop who’d filmed everything on his European tour with his movie camera.

‘How was your holiday?’ I asked him.

‘Don’t know. Haven’t watched it yet.’

Another time he returned after an ocean cruise and made the following comment: ‘I went to South America with P&O on a once-in-a-lifetime cruise,’ he said. ‘I wanted to see the world but all I saw was the sea. All I heard was how ships are kept together. Riveting! Quoits, cards, deck chairs and cabin fever. I’ll tell you what, never again.’

As for me the only boating I would ever continue to do would be on ferries.

The jumbo jet boom of the late 1970s would foster the idea of mass tourism.

These days tourists crawl around this earth like ants on a piece of fallen fruit. Yet their packaged tours enable one to see less and less of more and more. Four nights in Hanoi, Dubai or places formerly out of reach – but what to do in the days?

Mine would be one of the original pot luck unpackaged magical mystery tours. First thumbing lifts through the vast arid spaces of the Outback with their promise and threat.

Into the Never Never

I hitched solo from Gunnedah through outback Queensland to Alice Springs. From there I aimed to pick up the main road north through the rugged heart of the country. After reaching Darwin, the gateway to Asia, I would carry on north through Indonesia.

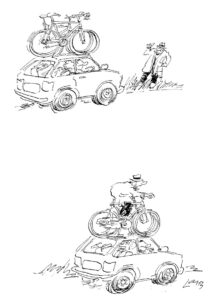

I packed my rucksack with all kinds of accessories to tide me through this trip. As well as my sleeping bag – my napsack as I called it – I had medicines, stove, cooking pot, pan and books about the country I’d be visiting. Dad said to me, ’It looks like you’ll be doing some trading with the natives.’

Mum said, ‘I’ll be so worried about you.’

‘In case anything comes up, Mum, I want you to remember that I’m type O positive. Okay?’

Sometimes this roads scholar stood for hours or even days in the same spot in searing heat or what passed for shade in order to catch the next lift across many miles of flat, dusty outback. Never saw the sun shining so bright. At midday it was hitting well over one hundred degrees fahrenheit. Often those first few hours would just be standing by the side of the road playing time games with my watch, kicking rocks around or throwing rocks at trees. The conditions made hitchhiking difficult.

The oppressive heat, the flies and the rough and unsealed roads were complemented by some lairising drivers who rejected the rules of the road.

I passed places with strange names that the tourist rarely see, tiny ‘one pub’ towns that dot the lone highway at irregular intervals, where drivers only stop to re-fuel and eat before embarking on the next leg of their long distance journey into the ‘ghastly blank.’

I no longer associated bridges or rivers with water.

Late afternoon came the cool magic hour settling over the plains, the receding sunlight over dry flatlands , tiny little towns with wire fences going grey in the advancing dusk.

Leaving the Alice, the temperature climbed to the high 30’s C on that morning. It was then I realized that asphalt has a liquid state. I swear on my brow I could hear the trees whistling for dogs. Drawing great rolling arcs in the air with my right thumb, I walked until the last houses were behind me. I was standing in the same spot all through the morning heat. High noon arrived with the sun blazing down directly above my head. The effects of the bright light and heat were compounded by the fact that it was also reflected up into my face from the melting road. There was a steady stream of cars passing but no-one stopped. None even slowed down so much as to take a look, never mind appear to have any room inside. I needed a shapely companion to hike up her skirt and reveal a little leg while I waited a discreet distance behind.

Maybe it was the sheer distance involved between towns. To cheer myself up I decided to cool off with some tea at the small but packed roadside service station cum cafe I was outside of. The proprietor was cooking eggs in a frying pan full of grease. She took one out, inserted it between two slices of bread and places it in front of a truckie who inspected it doubtfully before biting into it. Yolk ran out of the other edge.

‘Would you like anything else after that?’

‘What about a stomach pump?’

I had no sooner sat down when a four wheel drive pulled in. Out of the cabin jumped just one man. With his Bermuda shorts, long socks and tie, he looked like a middle-aged businessman or government official.

After he sat opposite me and we both considered our order.

What’ll you have?’asked the waitress.

‘What’ve you got?’

‘Steak,egg and chips.’

‘Anything else?’

‘Steak and eggs without chips.’

The four wheel driver and I both ordered. Noticing a lip-sticked cup on the table, I called the waitress over, handed it to her, and said, ‘Make sure my glass is clean.’ A few minutes later she returned ‘Which one of you blokes,’ she asked, ‘ordered the clean glass?’

This humorous incident enabled me to strike up a conversation with my fellow diner. I asked him royally, ‘Heading north, are we?

‘I don’t know about you but I am. I’m headed for Utopia.’

‘Good for you. I’m glad to hear someone is. I’ve long wanted to go where everything is perfect.’

‘I’m talking about Utopia Station, the pastoral lease.’

‘How far away is it?’

‘It’s 260km away or thereabouts.’

‘What takes you up there?’

‘I’ve got business with the lease holders. I have to monitor procedures there.’

‘I’d really like to see one in operation,’ I said, dropping a not so subtle hint.

‘Who are you,’ he asked.

I’m Allan,’ I said, extending my hand. I’m a student at Armidale, I’ve just turned twenty, and I’m heading up to Asia. Does that say enough?’

‘It’s a good start. I’m Trevor, by the way.

‘I’m pleased to make your acquaintance.’

‘So what sparked your interest in pastoral leases, Allan?’

‘It wasn’t so much what but who. It was Bill McClymont, a professor at U. N. E. He gave a talk on them in my college.’

‘Bill McClymont, eh. Why didn’t you say so? Now there’s a pioneer, much to my liking’.

‘You know the Professor?’

‘I worked together with him briefly for the N. S. W. Department of Agriculture. Anyone who’s anyone in agricultural science knows of his work on animal nutrition, and that he holds the chair in rural science.’

‘He had to borrow a chair at its inception. His office did not have one for him to hold.’

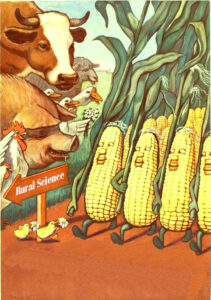

‘Well he’s put his school on the map despite this humble start, integrating animal husbandry, veterinary science, agronomy, and other disciplines into the field of livestock and agricultural production. He’s particularly interested in artificial insemination in pigs.’

‘Procreation without recreation,’ I said.

‘No poke in a pig. Another of his focuses is how to utilise the most efficient methods of sprinkle systems for plants in arid areas like here.

Now Bill’s become identified with the phrase ‘Sustainable Agriculture’, linking ecology with rural activities. He recognises the vital interaction between animal and plant production and in a healthy ecosystem of the first magnitude.’

‘Hence his motto: ‘All Flesh is Grass’. From the Book of Isaiah. No matter what we eat, it comes from the ground, from plants such as grass.’

‘That’s it. Animals consume the grass, making it a part of their bodies. Chickens eat seeds and plants make the seeds. Cattle eat grass, so if you love steak, there you go. You would like as an accompaniment the best potatoes and peas.

Bill is working on ways to increase the size of corn kernels as well as their length and number in rows. Oil, sugar, wheat, chocolate, corn come from plants, too. Then when we die all us animals become plants as we decompose.’

‘Pushing daisies.’

‘That’s just one of endless possibilities. Look, you’re after a lift aren’t you. Well, you won’t get one from here after midday. You’re welcome to come with me if you want to see some real Australia.’

‘That’s very kind of you. I assure you I won’t get in your way.’

‘You can ride shotgun. It’s a long drive and you would help keep me alert.’

Wouldn’t I need a special permit to go there?’

‘Just leave that to me. Any friend of Bill McClymont is a friend of mine. Bill is as clean as a hound’s tooth. I wouldn’t expect anything less from you. The thing is I’ve got a son your age hitching around Asia at the moment. I like to think someone there would do the same kind of thing for him.’

‘Will Utopia get me closer to Darwin? I asked.

‘No’, he replied, ‘it’s north east of here. But it will get you closer to some very special Australians. The original ones. I’ll do my business at the main homestead and around the station before heading back here in several days’ time. You’ll have to stretch out and kip in my machine. I take it you don’t mind roughing it a bit.’

‘I’ve been doing plenty of that the last week.’

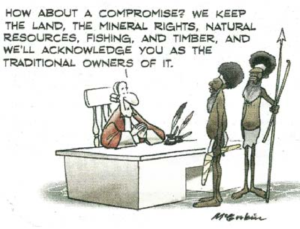

‘What is a pastoral lease in the legal sense?’ I asked as we awaited service. ‘Some friends I know from the agricultural faculties are working in them since graduating.’

‘The pastoralist does not own the land, but pays rent to the Crown. At the expiry of the lease, the land reverts to the Crown.’

‘How long has this kind of leasehold tenure been going on? When did the pastoral settlement of the region begin?’

‘Utopia became what it is today in the 1940s. Leasing evolved last century to control the activities of squatters and to protect the rights of indigenous peoples. By granting pastoral leases, governments retained both flexibility and control over the vast tracts of land used for pastoral purposes.’

‘It helps them keep their options open.’

‘Exactly. And my work in Primary Industry is to make sure that the leaseholders are complying exactly with government regulations. It’s on them to prevent over grazing and land degradation. A lease reflects the desire of the pastoralist for some form of security of title. It reflects the clear intention of the Crown that the pastoralist should not acquire the freehold of large areas of land. The future use of these cannot be readily foreseen’.

‘Ideally they should revert to ownership by the original inhabitants. They are the traditional owners, after all.’

‘Maybe the menu will make it here this century’, I said as we started to eat waited at our table. The service is as slow as molasses and the cuisine no better.’

‘Nor were our tips.Looking down at her’s as we got up, the waitress said, ‘Thank you so much,gentlemen.I can retire now.’

‘Wasn’t the food at that joint just terrible?’ said Trevor, wrinkling up his nose as we drove off from the service station.

‘You’re telling me. And such small servings. We’d be better off barbequing some roadkill. How did you find your steak?’

‘I just moved a chip and there it was. I misinterpreted the menu’s meaning of ‘minute’ to describe the steak. The eggs were lousy. The chickens who laid them should be ashamed of themselves.’

‘More likely it’s those who raise the chickens. They keep the chickens in tiny battery cages where they become frustrated and fearful. Not to worry. We’ll get a good feed where we’re headed.’

We finally got onto the dusty red dirt road leading to the main homestead.

The country was mainly stumpy mulga scrub and spinifex on red sandy flats, broken up by dry river beds lined with gum trees and paperbarks.

In the heat of the afternoon, the horizon shuddered like a mirage, tumbleweed blew along the earth and towering dust devils swirled across the road. We drove several hours without seeing only the occasional animals. Feral horses, camels, and braying donkeys that ran around out out in the scrub.

Pink cockatoos darted out of the bush and swooped over our vehicle, a few exploding into the grill in a suicidal puff of pastel feathers.

‘This is Big Country,’ I said.

‘The run covers an area of 3, 500 square kilometres,’ said Trevor, my host. ‘It is large enough to have more than a day’s travel between different parts of it. This is the rangeland pastoralism of arid and semi-arid areas and the tropical savannas. This grassland seems ageless, and in the places where man has built his outposts, he seems to huddle in the centre of a limitless space.’

‘The plants are entirely indigenous, I believe.’

‘As you can see, the vegetation growing is primarily native, rather than plants established by humans. You wouldn’t recognize these after the rain which is very infrequent. Then the dried-out spinifex flowers can resemble a field of wheat and the mulga shrub bears green dense foliage and masses of bright yellow flowers. Growing amongst these plants is an abundance of wildflowers that turns the deep red coloured desert floor into a utopian garden.’

We nearly struck a stray bull wandering along a bend in the road. It didn’t seem particularly interested in moving. If we were to have struck one of these hefty beasts, there would have been nothing left of us or the vehicle. Then up rode a quick sighted aboriginal stockman wielding a stockwhip who fearlessly drove the bull off to clear our way. He impressed me the way he stuck so close to the saddle.

‘This one is a gun horse breaker and overseer tasked with hunting wild dogs. No man on earth is more proud than an aboriginal man on horseback,’ said Trevor. ‘They look upon themselves not only as equally good, but as better than their white counterparts. You can see why.’

‘And this coming from those to whom horses were only recently introduced.’

‘Can you imagine the fear the horses and cattle struck into the locals when they first arrived? They believed the unfamiliar creatures to be devils. Sometimes they thought the horse and rider, observed from a distance, were thought to be a single monster.’

‘As thought the Amerindians about the conquistadores.’

‘Utopia’s carrying capacity is one beast for every 60 acres. So you can imagine how much lebensraum this fellow has. This is low-intensity land use. Rangelands such as Utopia are run principally with extensive practices such as managed livestock grazing.’

‘They’ll have to manage this fellow’s road manners better.’

Groups of aboriginal women walked near the road.

‘What are they doing out here in the middle of nowhere?’ I asked.

‘They could be out visiting relatives or moving between the outstations, the subsidiary dwellings that are spread out over a great stretch of country. They wander the sods of spinifex and dig out succulent honey ants and witchetty grubs from the roots of trees for eating. They might be collecting bush plums or bush tomatoes or seeking out desert plants. They make batches of medicines, relying on ancestral recipes.

‘The Alyawarr and Anmatyerr peoples who’ve stayed in this their country roam more or less freely. It’s their traditional homelands. Home to the oldest human presence on earth. Rosalie Kunoth who played the role of ‘Jedda’ is one of the Amatjere people, one of the oldest in the world.’

‘I recall her name in the credits as ‘Ngarla Kunoth’.

‘In their flower arranging version of aboriginality’, the Chauvels sought a name that would seem more appropriately Aboriginal to white filmgoers. As a teenager she was selected by Chauvel to be an ambassadress for the tribe in film art.’

‘Her film presence in ‘Jedda’ , is as iconic a one in Australian cinema as Chips Rafferty, Peter Finch or whoever you’d like to name,’ I said.

‘These people have close kinship ties. The land is central to them for cultural reasons.It has always been their bread-basket.

They see their role as it’s caretakers. They hunt and gather and stick to the requirements of tribal law. This dictates appropriate punishments for crime, birth and death procedures. It dictates relationship ties as well as ceremonies for creation or ‘dreaming’ re-empowerments and many other facets of tribal life. It guides mens’ and women’s business.’

‘What’s that about?’

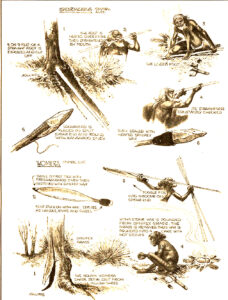

These are the procedures one goes through to achieve adulthood. In the men’s ceremonies they sing songs. They paint themselves with red ochre and tie emu feathers around their feet. They make string from human hair and wrap it around their heads. The boys learn the lay of the land, how to make things out of wood. and all about bush medicine.They live on their own bush food-bush potatoes,tomatoes and bananas.On honey provided by sugarbag bees. On graduating as men, the initiates wear a red arm band.

The casual traveller wouldn’t see a lot of this. You need to have closer contact to observe other activities of collecting and processing bushfoods, hunting and general ceremony.

We finally arrived at the ‘Three Bores’ homestead and after settling in gazed out at the scrub from the verandah. The land seemed smaller at night than during the day. The horizon drew closer, containing strange rustlings and restlessness, the sounds of wild beasts, and voices carried a great distance.

I was able to observe that very night some of those food habits Trevor spoke about.

Most of the descendants of the original people lived around the homestead in their camps. At the closest one, white haired old ladies were cooking big goanna lizards they had caught. One dragged a branch onto the fire and watched it burn. Later she poked at the fire stirring it to life. The others fed her bubs the blood of kangaroos hunted by their relatives.

’Hey Harold, where do you think you’re going?’ she said to their father as she caught him from the corner of her eye, attempting to slink out.’

‘You’ve got to watch these husbands closely,’ she said. Harold is like a fire, he goes out when unattended.

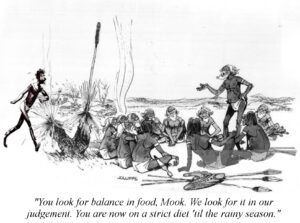

Precursors to today’s environmentalists, aborigines protected some animals which could not be harmed or eaten. This restriction applied to certain birds such as the Wedge-tailed Eagle, the Australian Raven and the Long-Billed Black Cockatoo. One of the elders told our gathering the following story about them.

‘Our people have different tales about the place of birds in the world, how they spread messages and lead people to safety if they’re lost. According the Dreaming, they are our totem, our tribe’s messengers who carry the spirit of our ancestors. We liken ourselves to these birds in reincarnation.

One of our young men who had been isolated from his tribe was caught in the act of killing an Australian Raven. He was brought before the tribal court and asked to explain himself. After the chief deliberated he pronounced, ‘’Mook Mook Eyes,This is an offence to our custom. These birds are special and sacred. I would hate to be anyone who’s going out and killing them. If they fail to have respect for the raven’s spiritual essence it could be the cause of unhappiness in the killer. That curse will be your payback. Do you have any excuse for this transgression?’

‘You’re right, O wise one, I have no excuse, it’s just that I was so hungry and they taste so good I couldn’t help myself.’

‘That certainly is no excuse, I would think you’d have better sense than to break the law and risk punishment just because the raven tastes good.’

‘That’s true, O wise one, but they really are delicious.’

‘Well, not that I would ever want to eat one, but just out of curiosity what does a raven taste like?’

‘Well, O wise one, the flavour is light and sweet like that of a Long-Billed Black Cockatoo, the texture a little tough like that of a Wedge-tailed Eagle. In other words it’s half way between!’

The chief ordered Mook to distance himself while the elders discussed his fate. The chief then summoned Mook and delivered the verdict:

‘I found that tale informative and humorous,’ I said as the story teller finished and after I clapped. How long have you been telling stories.’

He said, I’ve been telling stories since I was knee high to a bandicoot..

‘ When was that?

‘Oh, once upon a time … ’

A hush fell around the fire when the program came to song. A young buck we’d hear singing the following day appeared and said, ‘I’m now going to sing you some of the songs of my ancestors’

Whereupon he burst into singing, ‘When Irish Eyes are Smiling’.

He was accompanied by another playing the didgeridoo.

I thought to myself, ‘That’s aboriginal!’

‘Thank you,’ I said to him when they finished.

‘Will you be here next Saturday?’

‘We’ll be gone by then. Why’s that?’

‘We’ll be having a rain dance-weather permitting.’

‘What will happen?’

‘It’s a sight to see. Fragments of the rain stone are removed by rubbing, and go into the sky. They form into clouds. Then we throw our boomerangs into the sky to cut the clouds and allow the rain to fall.’

‘It must be very welcome.’

‘There’s nothing like getting under a good shower. But they’re scattered .You’ve got to catch one while you can .’

‘How do you know that song you sang ?’

‘My grandfather taught me that. He was Irish but we try to hide that.’

‘I enjoyed your rendition. What’s your name?’

‘Agira, ‘he replied. It means ‘kangaroo’, Cuz.’

‘You don’t hear a name like that every day.’

‘Yes I do.’

‘My brief stay at Utopia would give me the opportunity to experience first-hand the leasing set up and, if only for a few days, how the other half lived and worked.

‘Who is responsible for developing the infrastructure here? ‘I asked Trevor. As we looked around at the fences, yards, bores, accommodation.’

‘They are the right of the lease-holder.’

The infrastructure of the camps was somewhat more simple. There was neither school nor any health clinic. Some people lived out in the open or in the rusting shells of derelict old wrecks of cars.

‘You can imagine what it’s like in the cold wet winters,’ said Trevor.

Many spent the bakingly hot days in rough shelters, alongside their dogs.

As the majority of the people at Utopia spoke very little English, I relied on Trevor to act as my guide. Showing me around, he explained things as we travelled around on jarring rutted desert tracks, ‘I’ve come to be very respectful of the local people. When I accompanied a soon to retire departmental officer in my younger years, I found out what can go wrong when this is absent. We once pulled up at a fence at one of the outstations to carry out a soil analysis.

An aboriginal boy about fifteen years of age accompanied by a cattle dog was leading a foreboding looking bull along.’

My partner got out of the vehicle and approached the lad. I followed suit.

‘That’s a pretty mean looking bull you’ve got there. Aren’t you scared?’

‘He’s not the biggest baddest thing here. He knows me longtime. Anyway he’s got nothing to prove. It’s the teenagers like me that are trying to move up in the herd ranking that are constantly skirmishing. They are much more likely to get aggro with you.’

‘Who wants to end up steak?

‘Do you feel safe?’

‘And as you can see, I always have my Blue Heeler as back up.’

‘Where are you taking this tank on four legs?’

‘I’m taking him down to the far pen to mate him with the heifer.’

‘That’s a risky job for a boy. Can’t your dad do it?’

‘You don’t know my dad. The bull can do it much better.’

‘Where is your dad?’

‘Over there,’ he said pointing to the fence.

Small of stature, lean and sinewy, his face framed by a straggly grey beard a mass of woolly hair with a wide brimmed bushman’s hat perched atop, an aboriginal stockman was polishing a saddle astride the fence. My partner said to him, ‘Morning Jacky, I’m from the Department of Primary Industry. How you like our land management?’

‘O. K. Boss. And how you like our land?’

‘The sooner I’m out of it, the better. Now I need to inspect this area to test the soil.’

The stockman reluctantly said, ‘Okay, but don’t go into that paddock over there… ’, as he nodded his head towards the direction.

My partner got wound up like a cheap watch and said, “Look mister, I have the authority of the federal government with me!’. Reaching into his rear back pocket, he took out an official letter and displayed it to the station hand: ‘See this letter?! This is my mandate.’

‘Who you go out with is your personal affair, Boss.’

‘This authority means I can go wherever I want, whenever I want, on any land I’m told to! No questions asked, no answers given! Do you understand, Jacky?’

‘Jacky’ nodded kindly, apologized and went quietly about his business. Moments later I heard loud fearful screams. My partner was facing a sturdy bull snorting and pawing the dirt, flinging dirt up onto his back before rocketing towards him. As he ran for his life the bull was gaining ground and it was likely that he’d sure enough get gored before he reached safety. He was clearly terrified. The stockman stopped what he was doing and yelled out to him at the top of his lungs.

‘My partner was fortunate to make it to the rundown fence and scramble over safely.’

Of a quiet disposition, this quality of the locals gave them self-control and a contentment so often shown on the pleasant smiling faces of the elderly. This was beneficial to them in their work where calm collectiveness was advantageous and essential. While a limited number of Utopians were employed on the station, I saw how much it depended on them to perform all the essential tasks and services. They worked in every facet of stock work: mustering, boundary riding, tracking, tailing, droving, breaking in horses, cattle-dipping, branding, ear-marking and separating weaners. They appeared to know every animal and gave them great care. On top of this they worked as blacksmiths, cut wood, and did the tanning, fencing, butchering and rabbit catching.

The men did the saddling and took great their pride in their whips and spurs. While one man sat on the ground carving intricate whip handles, another straightened spears with much skill and patience.

He had a supply of boomerangs.I had forgotten how to throw one but under his guidance it soon came back to me.

I told him, ‘Alistair McAlpine,a rich businessman in Perth likes throwing them.He took one back to England.’

The women worked as domestic helps and did gardening. All were indispensable for guiding the whites through the landscape.

‘Now you know why aboriginal stockmen are highly valued and respected workers,’ said Trevor as we entered the station store, itself a mere tin shed. An old man was whistling as he loaded sugar, flour, tobacco, shirts, trousers and dresses onto a bench and handed them out to a line of locals.

‘And what do they get in return? I imagine their wages are low.’

‘Wages? What wages? The lucky few may get a few shillings a week but none are paid at anything like the same rate as white people doing similar work. They may provide necessary labour for the station but it’s dirt cheap and it’s seasonal. In exchange for their labour they got food rations, blankets and clothing. This is the ‘fodder and harness’ method of payment. They have no choice but to buy any extra supplies and clothing from the store at whatever prices the station owner charges. They never see real money. Those who work at the store can end up buying food and supplies with money advanced by the store. They can get into debt with it.’

‘Did you catch what the old fellow was whistling, Trevor?’ I said after we left the store.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know. Music’s not my strongest point. What was it?’

‘Sixteen Tons. It goes like this. ‘You load sixteen tons, what do you get. Another day older and deeper in debt. Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go, I owe my soul to the company store.’

‘The whole process of coercing Aboriginal people with foreign food and goods at the same time as taking their land and interrupting their traditional lifestyle permanently makes them dependent on the whites. The theft of their land means that aboriginal people have been denied the right to choose a lifestyle. Their experiments with the culture of the whites has been impossible to reverse’.

‘The pastoralists would believe they have done them a huge favour.’

‘The more enlightened pastoralists believe that by going along with them, the aboriginals are satisfied with their new lifestyle. They would claim they have not forced this lifestyle upon aboriginal people nor brought it about through greed. Rather it was simply an inevitable consequence of the need to raise stock. They have convinced themselves the aboriginals think nought of the future or of posterity and are satisfied with the advantages obtained in exchange for the loss of their hunting grounds.’

‘The leavings and scraps from the kitchen, the slaughter-house and the cupboard. ’ ‘Many Aboriginal people have forsaken their traditional lifestyle for that offered by the graziers. However, the reality is that few had any choice. The pastoral industry infiltrated Aboriginal country and the people were forced to adapt. Many people were coerced by graziers into becoming cheap labour and forced to make the most of a situation over which they had lost control. they couldn’t ever expect life to treat them well.’

‘For them to expect life to treat you well is as foolish as hoping a bull won’t hit you because you are a vegetarian.’

‘Little if any regard was given by graziers to the culture shock they were causing and many aboriginal people experienced extreme suffering even while they appeared to be adapting.

Both parties have gradually learned to take advantage of each other. The pastoralist avails himself of the cheap labour furnished by the blacks, and the aboriginals have acquired a taste for what the white man has to offer, though it is of course mainly limited to tobacco, food and clothes. Of this change of condition the pastoralist reaps the whole advantage, for the invariable result to the aboriginal has been sadly too often both mental and physical degradation and retrogression.’

‘And what about the less enlightened pastoralists?’

‘In the process of pastoral expansion aboriginal people have been treated with varying degrees of tolerance but always as illegal occupiers of their own land.

Lies are always spread about them. They are still frequently depicted as lazy, shiftless, drunken bludgers looking for handouts, ‘wasters’ who ‘burn down’ the houses they are given. There are always attempts to drive them off their land.’

‘What happened to those who’ve left Utopia?’ I asked Trevor as we headed back to the Alice.

‘Some were displaced from this land into overcrowded remote communities and fringe camps of major towns . They often have run-ins with the law. They have their own version of Monopoly – just one big square that reads: ‘Go To Jail’. There are those who lost their former self-reliance and independence after they acquired the habit of relying on what they could get from the white man. Traditionally they could track man or beast over land, through the air, underwater. Nowadays they have a job keeping track of the days and keeping off the white man’s poison.’

‘How do they cope with this?’

‘They have a great sense of humour. I was once driving on the main road near the turnoff from the Alice when I came upon a tourist bus pulled over to the side. The passengers were standing round a man lying at the edge of the road. He had one ear pressed to the ground and his hat next to it.

‘He must be listening for the sound of kangaroos, emus or runaway cattle,’ one of the Americans informed the others. ‘They can hear things for miles in any direction.’ He asked the prostrate man, “Young man, what are you tracking and what are you listening for?”

He replied, “Down the road, not within a bull’s roar Boss, is a rusty old Holden ute. It’s red. The left front tyre is bald. The front end is out of whack, the fan belt is busted and it has dents in every panel. There are seven blokes in the back. They’re all drinking flagons of warm red ned. There are three kangaroo carcasses on the roof rack and four mongrel dogs on the front seat.”

Everyone was amazed by this precise and detailed knowledge. This man knew what kind of car it was, that it was a great way’s away and what was in it.’

“Goddammit man, how do you know all that?” said the tourist.

He replied, “I fell out of the bloody thing about half an hour ago.”

‘Can blokes like this really sense distant ground vibrations?’ I asked Trevor.

‘Seismic stimuli have a role in animal communication and prey detection . This man’s obviously good at detecting. He went away with his hat full of cash. However, seismicity is less pronounced in humans than in other animals, especially smaller ones. Like all creatures, humans perceive with limited spectra and sensory modes. We bias research with the unconscious and incorrect assumption that other animals ‘see’ the world as we do. Every time we discover otherwise, it expands the horizons of scientific knowledge and sends us the humbling and vital message that we are not, after all, the measure of all things.’

So can we rule out the importance of human seismicity altogether?

‘It’s possible that humans may also have used seismic cues at one time as a means of detecting prey and in long distance communication. Recent tests by the U. S Department of Defense show that a man jumping on the ground generates a seismic disturbance measurable at one kilometre away. These signals travel much further than previously expected. The measurement of a man jumping was made to confirm that even relatively small seismic disturbances generated by a large mammal are measurable over great distances. Low frequency drums or the digeredoo could have been and may still be a form of seismic stimulation, as well as traditional dance involving stomping. Humans may once have used seismic stimuli as a mode of communication when the ground was a quieter environment.’

‘As it still is here,’ I said.

Humans may have used seismic signals at one time as a traditional means of communication, but the seismic channel may no longer be necessary or even possible for humans to tap into. The increase in seismic noise is pervasive throughout the world.’

‘What about all that stomping in Maroubra? I said, referring to the recent dance craze in Sydney. ‘Wouldn’t all that “bioseismic pollution’ drown out the dance vibes or just cancel them out?’

‘Some older folks in the area might reply ‘Hopefully. ’ Seismic communication is a relatively unexplored modality of communication in large mammals. We may find new answers to old questions and generate new questions by exploring this phenomenon. We humans may not be as remote from this world of communication through vibrations as we might believe. This is why the tribal people you saw in Utopia still sit upon the earth instead of propping themselves up and away from its life-giving forces. For them, to sit or lie upon the ground is to be able to think more deeply and to feel more keenly. They can see more clearly into the ineffable mysteries of life and come closer in kinship to other lives about them.’

Asia,here I come.

After my trek through the Outback I finally arrived at Darwin, in Australia’s tropical ‘Top End’ and spent an unforgettable week there in the punishing humid heat, my clothes completely heavy and damp. Anything or anybody that didn’t move would begin to mould. I felt sure even Tarzan couldn’t have stood that heat. I sought refuge in air-conditioned government buildings. Anyway, the time came to put air under my wings. I knew I was nearly at the airport because I saw this big notice saying ‘Beware low-flying aircraft’. There’s not a lot you can do about that, you know. I took my hat off just in case.

And my Swiss army knife handy. In that wonderful age of flight you could board a jet, sit back to enjoy a film and by the time it was over you’d be in some unscheduled hijacker’s destination. Several years earlier an armed passenger had demanded the milk run he was on from Sydney be diverted to Darwin or Singapore.

Some more of the glamour of my first big flight was lost on the way to the peninsular entrepôt. Why I wondered as I waited to board at Darwin Airport did they call it ‘the terminal’ if flying was so safe?

I think the fear of flying is quite rational because human beings cannot fly. Humans have a fear of flying the same way birds have a fear of driving. Put a bird behind the wheel of a car, and they go, ‘This isn’t right. I shouldn’t be doing this. I don’t belong here.’

Then sitting on the runway, the hostess told us passengers to keep our seatbelts on because something could go pear shaped with the plane. They never told me that the wings could fall off or we might end up in the drink when I was buying the ticket. Up, up, away and ten minutes into the flight she announced that if by any chance the pressurisation of the cabin drops, an oxygen mask would drop down.

They waited ‘till we were strapped into our seats at 30, 000 feet to tell us that!

My fellow passenger in the next seat wasn’t very reassuring either. ‘The masks don’t really help you anyway. They’re just there to muffle the screams. Do you know why they recommend we adopt the brace position when instructed? So if we crash your teeth won’t be smashed and your dental records can be used to identify your body.’

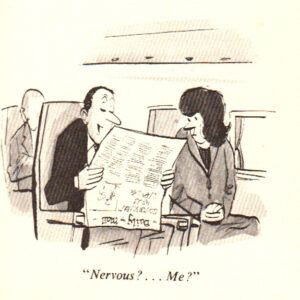

Passengers vary in how they handle their first flight. One couldn’t conceal his nervousness.

Another passenger who’d been drinking steadily made light of the situation: ‘People if we’re in a crash, please do not despair, grab a mask from above your head and suck in lots of air, whip on your life jacket, tie it very tight, and pray to God that we’re in luck that all will turn out right.’

Once we were well on our way I relaxed and pondered the strange wonders of the modern age. While eating a chicken sandwich I thought ‘I am eating a bird while I’m flying. I, a flightless land mammal, am consuming a bird in midair. After which I read my in-flight magazine and sipped a Bacardi and coke in a cloud.

On the seventh day, the Israelites got up at daybreak and marched around the city seven times in the same manner, except that on that day they circled the city seven times. At the seventh time, when the priests blew the trumpets, Joshua said to the people, “Shout! For the Lord has given you the city.…’

Joshua 6:15

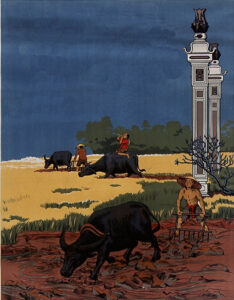

After flying without incident to Singapore, that fine clean city state-you’ve got it-my first asian port of call, this rangy rover hit the road,in the wake of the Old British Empire, along lotus scented streets and sidewalks splotched with red betel nut residue, up through the west flank of Malaya to Penang via Kuala Lumpur. Waiting under a durian tree, I nearly got clocked by one of its thorny fruit falling down. It wasn’t the wonder of Newtonian physics that that flashed my mind. It wasn’t the distinctive strong and penetrating odour of its edible flesh. It was its strong and penetrating effect on my skull. They kill numerous people each year when they ripen and fall on unwary heads, as do coconuts.

I was already familiar with the scenery of Kuala Lumpur and its environs from the William Holden movie, “The 7th Dawn”. In reference to the biblical Battle of Jericho won by the Israelites during their conquest of Canaan, the British hoped for a swift end to their war against the Communist rebellion. According to the narrative, the walls of Jericho fell after Joshua’s Israelite army march around the city blowing their trumpets. as the walls came tumbling down.

Seeing all the bicycles pedalled around the central railway station and the moorish style Clock Tower complex in Kuala Lumpur took me back to the scenes where the British attempted to place a curfew on their use. They were concerned they could be used to transport grenades or bombs. I remembered the protests against this ban, led by a Eurasian, Dhana, head of the schoolteacher’s union. This was during what the British called “The Malay Emergency”, the emergence of Communism in South East Asia following WW II. While the French were fighting the Communists in Viet Nam, so were the British and Australians here.

I passed by the rubber estate and rubber tappers at work who were filmed on the Kuala Lumpur trunk road to Negri Sembilan.

Skirting alongside the lush, virgin splendour of the rain jungle Skirting alongside the lush, virgin splendour of the rain jungle at Ulu Gombak, I remembered the two former friends who fought the Japanese having to slog their way through it on opposing sides. Holden’s character, Ferris, had become a prosperous rubber plantation owner, while his adversary Ng was a guerilla leader. As a Party member, he was expected to view the matter of ownership according to a strict class basis. Yet how could he argue with Ferris’ right to be prosperous. He had won it with his bravery, at great cost, and was not touched.

At the same time many Malaysians who had fought against the Japanese invaders were poor. For Ng and his former comrade, their bone of contention was over how high a level of prosperity the individual could enjoy in the midst of great poverty. Ng genuinely believed that the Communist revolution in China was on the road to eradicating wide differences in income in favour of the proletarian.

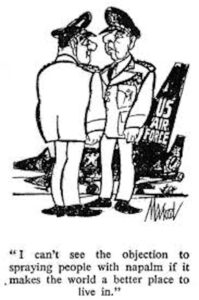

Having gone to Moscow to obtain an education, on his return he was to go all-in as a revolutionary. A Malayan Chinese, a native of implacable hostility and dedicated vision, he was determined to destroy “”the soul, spirit and symbol” of colonialism, to strip away it’s enlightened facade. Following attacks on British interests, their administration reacted just as the U. S. would do in Vietnam and Israel does still in Palestine. carrying out what Major General Yehuda Fuchs, a senior commander in the Israeli military, would term a ‘pogrom.’ The British ordered reprisals, burning an entire village said to be aiding and abetting the enemy.

I remember the story’s attitudes about Communist rebels and British colonialists as unusually intelligent and shaded for the time. At a time when Western world films generally depicted all communists as slovenly, freedom hating monsters, The 7th Dawn was notable for making Ng sympathetic and his anger entirely justified, while still critical of his extremism and condemning his terrorists acts. Conversely, the British came off even worse, with their condescendingly paternalistic intractability and shock-and-awe strategies. When they torched an entire village – and it’s a big one, not just a few huts-the horror and anger on the faces of its displaced children, sick, and elderly is compelling. The weeping and wailing were genuine as I was told on the spot where the village had stood. Squatters had moved into the set as soon as it was built, only to lose their new homes during filming.

The movie was banned in Malaysia and is still highly sensitive today. A surprisingly good political drama with lots of action and adventure, it didn’t go over well either in America, where the war in Vietnam was just beginning to heat up.

I stayed with my college friend Nick Mohomed. His brother offered to show me around. On arriving to pick me up, he asked when I was getting ready. I assured him I was dressed but he looked uncertain.

‘What as?’ he said. ‘Men should cover themselves from the navel to the knees.’

My bermuda socks weren’t halal. Funnily enough, I would agree with him later, but on fashion grounds, not for reasons of propriety.

In Penang I was offered hospitality by an Australian officer stationed at the Royal Australian Air Force base there. While there I discussed with him the possibility of getting a lift back to Australia on a RAAF plane on my way back from further north. Unlike earlier well-heeled visitors, staying at fine colonial hotels with flocks of starched servants, I chose to sleep on the floors of railway stations or in cheap dives. Travelling through Malaya now and again I would bowl up to police stations and stay overnight which was an eye opener. This was travelling on a shoestring in an area where most people lived as such all their lives.

In Thailand

I passed the American air base in Ubon. F-4 Phantoms took off on flying combat missions over Vietnam. The sound was deafening. In front of this complex stood a tiny bar optimistically called ‘Victory Bar. The TWe hardly slept that night due to the most deafening sounds of planes taking off and landing. What I remember most about this was the almighty noise that the jets made–the likes of which I had never heard before.

I hitched with truck drivers, their cheeks bulging, chewing, or rather sucking on betel nut to keep themselves alert on long hauls. I didn’t need any, their vehicles having no suspension. While their radiators hissed, their engines spluttered, wheezed and knocked, their bodywork juddered and rattled. Each pot hole would send me up into the air, only to crash down in a stomach-jolting heap. What I remember most about this was the almighty noise that the jets made – the likes of which I had never heard before.

The drivers’ other habit was speed. Up to their axles in debt, they had tight schedules to meet. One hand wet on the wheel, one on the horn, they never stopped even to stretch their legs. I hung on tightly as they floored it, fishtailing from one side of the road to the other, careening round hairpin corners and passing others three-a-breast through blind curves and tiny villages. Every time we hit a pothole, I’d shoot up in the air.

I must have been really tired travelling with the last Thai truckie. He told me his father had been one too, working for an Australian company. ‘I learned to drive at my father’s knee’, he said proudly. ‘He never stood in my way.’

‘Have you been involved in many accidents?’ I asked.

‘No, but I seen a number in my rear view mirror.’

I fell asleep not twenty minutes after entering the cabin. As I lay sprawled out, my head resting against the door, the truck must have hit a big hollow. I hit the roof really hard.

‘What’s wrong? ’he said.‘You should see your face.You so pale. You look like you seen a ghost.’

‘You’re not far off’, I replied. ‘Listen, driving trucks is number one dangerous. If you drive like this you will break down or break your neck. Can you do any other job?’

He repeated the question.

‘So you say yes or no,’ I said.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Yes or no.’

‘I think driving’s in your blood. You mean to say ‘No’.

‘If I cannot drive, I would rather die.’

‘If you continue like this, others will die.’

He said ‘Is O. K. ‘I want to die peacefully in my sleep, like my father. Not thrashing around, quivering and crying like his passengers. Not retching and begging him to slow down.’

‘You have to try and stay calm and collected even in vehicle crashes.’

‘Like the last hitchhiker I picked up.’

‘Why, what happened to him?’

‘He stayed calm but after I collected the bus he’s still being collected.’

It was only on approaching the border did I see that the front two tyres had the inner tube protruding through the tyres. Both rear tyres were completely bald. I’d seen more rubber on a french letter.

I had worked out what is the most dangerous part of any motor vehicle. The loose nut that holds the steering wheel.

The last thing I remember saying to him was ‘Keep taking your tablets!’

The Most Secret Place on Earth.

At daybreak, the light of day streaking the sky I caught my first vista of the mighty Mekong.

After crossing this misty, winding waterway, I teamed up with another truckie on an overnight truck ride to near Vientiane. The driver, a grizzled whippet thin hustler with a slightly vulpine face, cheekbones so chiselled you could cut yourself on them, greeted me with the words, ’My name is Sou, how do you do?’ Like many Laotians, he went by the name of Souvanna. The first thing I picked up about this unknown quantity was the wild glint in his ptotic eyes and his disconcerting stare. He looked as if he’d been up all night. His brilliant red-stained cupid bow’s lips quivered readily between a pout and a snarl. No gender bender, his choppers were likewise, a result of his masticatory habit.

We pressed on to his small stilted house where he put me up. Late that afternoon after dunking my head in the nearby stream to wash away the sweat and dust of the trip, I observed him packing the betel leaf-lime paste – chopped areca nut mixture into his cheek, making for a clumsy fit. I asked him about the effect it had on him. He said in pidgin ‘Looky, looky’.

Then, as the arecoline ginned up his parasympathetic nervous system, it was plain as day to see. His pupils dilated and his droopy eyes watered. It was hard for me to watch a grown man weep so. ‘O, Souvanna, don’t you cry for me, ’ I sang, unaccompanied, no banjo on my knee. It was then his salivary glands started secreting. He didn’t just slobber, he poured, and the ‘betel juice’ bucketed from his mouth tinted a deep brick red.

‘It make me feel strong’ he said, swelling out his chest, straightening his back, breathing deeply.‘ It lift me up and clean me inside. It stop me getting hungry.’

‘Don’t let the world get you down, ”I said to him as we parted company. ‘Keep on truckin’.’

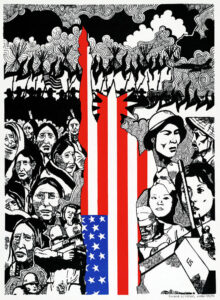

Years later I would wonder if Souvanna had somehow become the inspiration for ‘My Name Is Sue’ sung by the Man In Black. He sure had the gravel in his guts and the spit in his eye. These could have only built up in the following years as Laos continued to become the most bombed country in history, covered almost layer upon layer upon layer of bombs. The clandestine sideshow to the better known one raging next door.

Vientiane had something of a frontier town feel to it. Marijuana, used by the Lao for flavouring certain soups, could be bought in the markets. So too was the soup. Opium, a traditional medicine, could be smoked in dens across the city. In need of changing money, bank officials informed me I could swing a better deal changing my money on the black market. I thumbed my way towards the panhandle, perched on top of overloaded trucks, legs dangling over the side, or crouched in the back I scored lifts with Laotian military whose sandals,flip flops and rag-tag uniforms made them look like poorly fitted out boy scouts.

We passed cyclists with all manner of cargo crammed onto their simple machines. Some with porcine pillion passengers or those piggies carried in wicker baskets, cages packed with honking geese and chickens wired to their bicycles Others with towering pyramids of fresh flowers and fresh vegetables for the market.

I ended up in villages of thatch roofed huts on the way where people would gather around to find out about me. And me about them. The old woman with enormous fingernails. The young girl with an infant slung casually on her hips.

Being of novelty value, invariably someone would ask me home. Food, blankets, and mosquito nets appeared without prompting. Despite having no common language, one host family was soon plying me with green tea and pulling out boxes of photos, spreading the pictures of their children and friends across a low lacquered table and over the furniture for me to peruse. Children pressed up close, all around me, squinting quizzically. The elders shooed them away, but the shooing didn’t do much. All agog, the women inspected my clothes and face and giggled while touching the hair on my arms. But my host explained to wonderful me what transfixed them was other down: “You know it’s the hair on your chest that fascinates them, don’t you? Asian men have such bare skin.”

I replied with a Chinese saying: “Confucius says ‘Bird never make nest in bare tree.’”

The women tried on my sunglasses, and inquired about the use of odds and ends in my backpacks, like mosquito repellent or lip balm. They gasped in amazement when I flicked alight the lighter I carried.

‘Have they never seen one of these before?’ I asked my host.

‘Never one that worked the first time.’

They wanted to know where I was from and how I liked their country. Fragrant with wood smoke, festooned with blooms of mould, the hut had a split-bamboo floor and the sides of the building were constructed with plaited ferns and plaited palm leaves. You could imagine what that’s like in the monsoon. They had no modern-day conveniences, no plumbing or electricity… and upon noticing a small, fluorescent light bulb mounted to a support beam, I spotted the power source: an old car battery. While it was covered in dust and cobwebs, it seemed to be one of the family’s most valued chattels. They didn’t fuss about much. While the men swung lazily in hammocks, skinny dogs wandered around with proprietorial confidence, a litter of puppies scampered about, chickens pecked and rambled freely, scratching in the dirt outside.

A few yards away,two pots on an open coal fire smouldered in a corner.They were cooking beside what at first looked like a very large vine. On closer inspection, it turned out to be a freshly killed eight-foot python roasting in the coals.

The next day, back on the road, the American pulled up to offer me a lift. Over his toothy grin, he grew a Zapata moustache. He wore blue denim jeans, cowboy boots, bolo tie and his longish hair, tied back in a pony tail.

Ten gallon hat on his head. Almost white when it was new — sweat, dirt, and who knows what else, have stained the hat brown and robbed it of its shape. A fair description of the man as well.

‘Hi Mac, what’s the good word? Where ya headed?

‘To the panhandle,’ I replied, tumbling into his four wheel drive, studiously avoiding ‘Howdy, stranger. Anything doing?’

‘No shit. I’m going part of the way,’ he said after I told him my itinerary. ‘You’ve got yourself a ride .’

‘That’s mighty nice of you, ’I replied. ‘Don’t mind if I do.’ In fact, I’d have taken him up on his offer even if I’d felt less than welcome.

‘Are you a real Australian?’ he asked.

‘I was, the last time I looked.’

As we drove along, I couldn’t resist asking him, ‘What brings you to these parts’?

‘It might sound quaint but I work in import-export.I buy goods like gasoline internationally, ship them in for domestic purchases and vice versa.I export metals like gold from Laos’, he said, all hat and no cattle . ‘And I fly planes.Right now I’m on route to my base.’

We hadn’t gone far before the heavens opened up and it sheeted down. Then it was all mud, sweat and gears.

‘Listen, Aussie’, he shouted, over the sound of running windscreen wipers , waving and slapping time, ‘while this is the dry season, this deluge could set in a while.I have to turn off here.’

‘You can drop me off here.’

‘You don’t want to end up like Dorothy in the storm,unless you’re the Wizard of Oz himself. You might like to come with me to my crib in Marlboro Country. I’m happy to put you up ‘til things dry off. Come, come, it’s all in a good cause.’

He wasn’t the ugly American you heard so much about, loud and boorish. He was the quiet one, speaking not just gently but some of the local lingo. ‘I only have a few words of French and Lao but it’s enough to get the job done.’ he said. I was happy to go along with him.

Off the main road the tyres of his jeep squished over a muddy stretch close to collapse, rippling like a corrugated roof. ‘In Australia you drive on the left side of the road. Here we drive on what’s left of the road!’

In the ramshackle compound whither he brought me wood smoke rose, frogs leapt in the beam of our headlights and spindly children ran into view playing warplanes, zooming around, making their arms stretched out to the sides, level with their shoulders into airplane wings, fists clenched, thumbs pointed forward to represent guns. Imitating the noises of dive bombers, they circled and whirled, they weaved and dived until one of the ‘bombers’ fell down, feigning death grotesquely with appropriate sound effects as the valiant few circled him in triumph.

Sam picked him up and threw him in the air much to the child’s delight. He brought packets of chewing gum from the jeep to press into their hands: ‘A little somethin’ fer all y’all.’

To me he said, ‘Here we are, end of the rainbow.’

The area had an edgy, lawless feel. ‘So, this is Marlboro Country, ’I said.

‘Welcome to Dogpatch, capital of Marble Row Country!’ he said. ‘Your average stone-age community nestled in a bleak valley, between two cheap and uninteresting hills somewhere. Complete with hovels, hog wallows, hillbillies. Real ducky. I hope it’s to your taste. You can see it all from where you’re standing. Blink and you’ll miss it. The main road missed this one-horse, stagnant, malarial backwater. It’s not a place, it’s a disease.’

‘So nothing much has changed here over the years?’

‘Set your watch back a hundred years. The twentieth century has snubbed it. If you’re looking for the backside of nowhere, you’ve come to the right place. I can’t stand it’s suffocating anaesthesia. I came with low expectations and find it disappointing. If you want to feel better-looking and increase your self-esteem, move here.’

‘Surely something good sometime must have come out of here,’ I said.

‘Sure, and you’ve seen it. The track out of this bare-assed flyspeck sinkhole.’

‘Not unlike Dogpatch U. S. A.’ I reminded him. ‘A place unto itself. Unless you’re born there, you wouldn’t have a heck of a lot of reasons to hang around. Your own government – in ‘Lil Abner’, that is – completed a study finding it to be ‘the most miserable, unnecessary, no-account’ place on earth. This set the stage for evacuation of the town so that atomic testing could take place. A solution had to be found’.

‘What was that? asked Sam. My memory fails me now.’

‘Something that proved their town was a ‘necessary’ place after all. With Dogpatch in jeopardy and consternation abounding, the race was on to save it from becoming a nuclear wasteland.

Just as all seemed lost, Jubilation T. Cornpone, Dogpatch’s founder, saved the day. It seems his statue had been declared a “national shrine” by Abraham Lincoln, given all that Cornpone had done in bringing down the Confederacy during the Civil War.’

‘Consternation can abound here in the boondocks sometimes too,’ said Sam. ‘Things can go bump in the night’, he said. ‘But don’t fear, you’ll be all right with me.’ In fact, his shack seemed like an oasis of friendliness and calm. Especially after he offered me something to drink. ‘This calls for a stiff drink. Let’s break open the ‘Kickapoo Joy Juice’, from the mists of the Laotian moors’, he cried, drawing out libations of his home-brewed rice whisky from a large wooden vat. ‘This is from my private stock. The hooch in my hooch. Care to give it a go? It’ll sort you out. It’ll do you good.’

‘Never say no,’ I replied. ‘I’m ready for anything.’

‘That’s what I like to hear.’

‘How do you like your poison?’

‘I never have one more drink before dinner. But I do like that drink to be large, very strong, on the rocks and very well made. Shake it very well, don’t beat it, until it’s ice cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel. Got it?’

‘Here you go. Chin Chin. Throw it back,’ Sam replied, ‘It appears you know what you want- on the button.’

‘On the nose, like Bond – James Bond,’ I said, quoting the spy from Casino Royale, ‘a man who knows his liquor. So, what are we drinking to?’

‘To more drinking. Heck, that’s quite some firewater,’ Sam sighed, stretching out on his overstuffed sofa, quoting in turn Felix Leiter, Bond’s CIA contact. ‘This elixir is of stupefying potency. It can raise a blood blister on boot leather. The fumes alone have been known to melt the rivets off a B-52 overhead,’ he boasted.

‘I hope I stay alive long enough to enjoy it,’ I said.

He held his nose, he closed his eyes, he took another snort.

So did I. It went down and massaged my spine like fiery little fingers.

‘Bloody hell, how strong is that?’

‘Strong?’ he said.

He poured some of it out on to the wooden table and sparked it with his lighter. It caught instantly, he looked at me and we both laughed.

While insects throbbed in the humid air we spent the night boozing, schmoozing and slipping in and out of the vividly stylized language of Al Capp and an approximation of his characters’ mock-southern dialect.

‘Would yeh mahnd freshening this?’ he said over and over, handing me his glass, ‘and fix another shot for yerself.’ While I was slowly sipping it, he urged me to keep up with him, ‘Hit it. Don’t babysit it.’

‘Have you always drank such strong stuff ?’ I asked.

‘Before I came here, I never drank anything stronger than pop. Then again Pop would drink almost anything.’

I piqued his interest in discussing the state of play here with an outsider and telling it like he saw it. Relieved from his isolation, relaxed by the grog, he took me into his confidence.

‘Ah must be outside yeh usual frame of reference’, I said.

‘Ya sure are, buddy. But muh great grand daddy doggone it was a cowpunching trail driver. He trailed many head of cattle and horses northward from Texas to distant markets. Just like yer overlanders. Muh gran daddy fought with yehs in France, muh daddy fought with ya Aussies in the Pacific, so we go back a long way together. We spilled the same blood in the same mud. That makes us practically related, ya see. We’re kinda family.’

‘What about your great grandfather? Did he fight for the Union or the Confederacy?’

‘Neither I must confess. He fought for the West.’

Going out the back to relieve myself, with my ear to the ground, I picked up clues as to what kind of location I was at. Kaboom. I could hear the thunder-like crumps, whistles and roars and feel the jolting vibrations of the carpet bombing somewhere in the distance. There was no doubt what was happening there. ‘We’re not only within gunshot of the Ho Chi Minh Trail but of Vietnam itself,’ he told me.

‘Wal, fry muh hide!’ I said, what led a businessman like ya to stay in a place like this?’ I asked. ‘Just what do ya import and what do ya export? Coca Cola? Rice?’

He replied ‘Ah don’t work for just any company. Import-export’s just muh coverThe closest I’ve got to the fuel business is when I fill up with gas.The closest I’ve got to the business of gold is when my dentist filled my cavities with these,’ he said,flashing me a toothy grin.

‘Muh official business is a shell. After being sheep dipped, ah’m actually like Leiter, a case officer working on the ground for ‘The Company’.

Now ah am a pilot and muh name is Sam.’

Needless to say I was taken back a bit. He was not the clean-cut all-American boy I would have expected from a spook. But that was all his cover, part of his tradecraft. Not to stick out like a sore thumb.

‘Officially ya must be Cap’n Eddie Ricketyback, proprietor of Dogpatch Airlines’, I said, referring to Al Capp’s character.

That I shared with him knowledge of his old literary friends, his favourite cartoon characters, the denizens of Dogpatch, picked Sam up and he confided in me some details of his work. ‘I monitor the activities of Laos, watching and listening for any potential threats to the United States and its allies.’

‘That’s quite a large area.’

‘Hell and half of Georgia. I fly missions inserting and extracting U. S. special forces teams into Laos.’

‘Is this official?’ I asked.

‘Heavens no. I’m nothing more than a rumour. My status is ‘classified.’ Officially I’m not here. Like this piss stain Laos, lines on the map drawn by the French, without a railroad, a single paved highway or a newspaper, its chief cash crop opium, its people seeing themselves in tribal terms, I don’t really exist.’

‘I never carry a passport or other identification. No one, least of all the border officials, ever questions me about what I am doing. If they did I would have to refrain from answering, ‘pest control’. What I say to you never took place. America’s military involvement in Laos is covert. I’m a nonofficial cover operative.’

‘NOC NOC, who’s there? – Nobody. The truest practitioner of espionage. You’re breaking the law seriously aren’t you?’ I asked.

‘Ask a silly question. Of course I’m dedicated to breaking the law – foreign law.’

‘But still the law.’

‘As do the North Vietnamese. This whole place is crawling with coverts of all kinds. Laos is technically neutral. Consequently, our hands are tied in blocking the Ho Chi Minh trail thus isolating the battlefield. We are limited to Westy‘s second-best ‘find, fix and finish’ strategy of totalling up “body counts”, wearing down North Vietnam by creaming their units. This means I’m always out there, always alone. No safe house, support or extraction. I’m clean for now but unprotected. If something goes wrong, I’m on my own. ’

‘What if you are found out?’

‘If I’m caught, I’ll most likely be tortured, shot, or strung up. Just a grease spot.’

‘And here’s the best part – no one will ever hear about it.’

‘Is that for real?’

‘It’s true or my name’s not Sam.

‘Which it isn’t.’

‘You’ve got it. Like the names we assume, our successes go unreported. People don’t read a lick about them. Any responsibility for my actions will be explicitly denied. They never happened.’

‘Your superiors know they happened.’

‘They just haven’t forgotten them yet. My backstopped name will be disavowed, wiped away. Just a folded flag. No ticker tape. No medals. I’ll become a star on a wall, a blank space in a book, an afterthought at most.’

‘No citations for bravery.’

‘Fraid not. Only for speeding. As long as the Ho Chi Minh trail cannot be eradicated, this is a tricky proposition.’

‘So that’s where you come in,’ I said.

‘You got it’, he replied. ‘Instead of sending American ground troops to prevent a Communist takeover here, the Company runs thousands of sources. In order for the northern troops coming down the Trail to function operationally, they need a local infrastructure. Our assets inform us about these movements so their local power base can be eradicated.’

‘Just like that.’

‘It’s that simple. Using deniable funds, me and other operatives fly up and down the Trail, liaising with and leapfrogging these assets, smelling out resentment of the Reds, conducting photo reconnaissance, monitoring the traffic with sensors along infiltration routes, collecting various grades of intelligence.’

‘Doesn’t this covert war subvert the very basis of democracy where the Congress and public know what’s going on? At least from Vietnam the media send out a relatively independent, objective account of what is happening there.’

‘You know what the whole problem with the Vietnam War is, Allan? It’s too public. A secret war is the way to go. No reporters, no TV. You black out the war, then we can get on with our job. People need to be blindered so they don’t see too much. Like with those leather flaps our horses wear.’

The driver of my last lift had mud flaps. This one had flood maps. Noticing the compass, maps of all kinds and grid coordinates spread out everywhere in his listening post, I commented. ‘This is the frame of reference you must know best’.

‘I’ve had to become intimately familiar with the geographic coordinates of many places in Laos. From my field operations I can cite from memory the coordinates of specific towns or road junctions. When I’m not driving, I’m up in the air. I’m never still. I hopscotch around the country visiting villages. I meet everybody worth knowing-chiefs, officers, assets and so on. I see lots of things-machinery, weaponry, vehicles. I hear a lot of talk. Some of it backbearings.’

‘Backbearings?’

‘We gather information using indirect evidence or information to determine a fact. By determining what someone doesn’t know and is asking questions about, our agents can then determine what that person does know.’

‘Both ‘known unknowns’ and ‘unknown unknowns’ referred to by NASA. I presume.’

‘I get the straight dope on what enemy units in the offing are doing. I get to know what works, what fails, what’s new, what’s coming up.’

I get to know all about the villagers’ needs. We issue supplies, everything from weapons and ammunition to schoolbooks, medicines, rice and salt, uniforms, building materials, and money.We bury well hidden,secure caches of arms that agents can use to mobilize local militia. The Company has huge warehouses that can provide almost anything.’

‘How do you come across your sources? Do they come to you?’

‘We find them ourselves. We hire locals we trust to back the Laotian government in its fight against the insurgency. We give induction exams to Laotian boys to clear them for service in the militia. The insurgency’s like mah Kickapoo Juice. We’re gonna put it on ice. We instruct our boys to intercept convoys of supplies on the series of jungle paths snaking their way south.’

‘What do you do when you do intercept them?’

‘You don’t wanna know that.’

‘I’m going south too,’ I said, thinking of the next stage of my journey.

‘I’m headed thataway myself tomorrow. After I fix us some breakfast. You can come for the ride in ‘Bird Dog’ if you like’.

Bird Dog’ was the pet name for the ‘Cessna O-1.

‘I’ll show you something you’ll tell your grandchildren about. The Ho Chi Minh Trail. The centrepiece of the war. Do you want in?’

‘Natcherly!’ I replied, not wanting to get mixed up in any crazy caper, but seeing this as a rare chance to view where history was being made. ‘But don’t yo’ need the green light from higher up?’ I asked. ‘Ah don’t want you to get chewed out on account of me.’

‘I need me no go ahead. My buddies and I run our own show here,’ he said, ‘I can get in and out of the smallest field.’

‘Won’t you have to mention this unscheduled passenger in your flight log book?’

‘What unscheduled passenger!? I operate mostly on my own with no higher echelon, no rank, and few rules. We hit it off with the local yokels-better than our brothers do in ‘Nam. That’s how we get results. The top brass turn a blind eye to our rat-racing in Bird Dog.’

‘Come again?’ I asked.

‘Our unauthorized acrobatics. Which I’ll spare you from.’

‘No slapping the palm trees’. I asked, referring to a hedge hopping habit I’d heard about. Some American pilots got their kicks flicking over them with the aircraft’s underside.’

‘A’hm no crazy cowboy’, he assured me. ‘No loony tunes, just trackin’ the goons. We’ll be skirting along the western edge of the trail. No sweat. I know it from above as well as others know it from below. Then I’ll drop you off near the border, near ‘The Sihanouk Trail’, ’he said referring to this southern supplement. ‘Unless of course’ he said, you want trek the trail itself. I hear you Aussies are good at camping. We know that one of your countrymen passed along the trail a few years back. You might bump into him during the night.’

‘That must be Wilfred Burchett’, I said, thinking of this plump little journalist huffing and puffing up and down the Ho Chi Minh trail with Vietnamese guerrillas.

‘You could rig yourself out in a pair of black pyjamas like him and scrabble your way south.Sure, aerial bombardments could light you up, malaria, parasitic pests and dysentery could ravage your insides.No one would praise your effort.What would you be left with?’

‘No guts,no glory.’

‘ Jungle rot and immersion foot from sweating could disintegrate you; tigers could eat you; snakes could poison you; spiked vines, thorn bushes would trip you up, floods and landslides could wash you away. Otherwise you would meet some very interesting and interested people. Who maht just bash yore liddle haid in. Mind you if you made it through, it’d take several months.

‘Wal, cuss muh bones!’ I said, I’ll take my chances on yo’ Cessna. Ah got to be back in classes soon. In one piece. Now I think we need to call it a night and get some kip. We need to get up with a clear head. Right Sam?’

‘Zzzz’, snored the sleeper agent deeply, dead to the world, having drunk himself into a state of swinish unconsciousness.

All Quiet On The Western Front.

At the crack of noon a few shafts of sunlight sneaked through the windows. After things had dried out, myself included, I greeted the new day. ‘Good morning, Sam. Slept it off? Are you good to go?’

‘Not so loud!’, he replied,getting up somewhat precariously, holding his head and blinking. ‘I can’t see in all this light.’At last he got up on his feet,fumbled for his cleanest dirty shirt, stumbled over to the bowl in the corner and threw cool water on his face.