David Evans from his perspective spoke admiringly of Harold Coombs, this powerful banker who loved the theatre, and gave patronage to a range of endeavours towards giving Australia a flourishing art world.

‘Russel Ward knows him from his Canberra days. Let’s hear what he’s got to say.’

‘We had our doctorates conferred on us in the same ceremony at the Australian National University’, said Dr. Ward. ‘Something primitive in all of us expects great and powerful people to be commensurately outsized physically. Nugget wasn’t.’

‘It’s generally believed that tall people are better remembered for their achievements, isn’t it?’

‘What about Napoleon?’

‘Who?’

‘When it comes to getting a job done it’s all about attitude and confidence. I have seen guys six feet in height slouching and speaking like mummies and people the size of Nugget bursting with energy and persona. It’s all about how you carry yourself.’

‘What about his thinking’ I asked?’

‘They say good things come in small packages. In his case, it’s true. Nugget values intellectual vigour highly and approaches learning as a polymath, a scholar all about knowledge of the broadest kind. He dabbles in everything.

‘He’s interested in ‘the big picture’’.

‘A polymath if ever there was one,’ said Dr. Ward. ‘And one with a cautionary tale for teachers.’

‘How so?’ I asked.

Like all chalkies, Nugget, David and I dreaded the visit of the school inspector. It was a stressful time.

What was the purpose of their coming?

They came to assess our professional competence for promotion on merit and to give professional guidance.’

‘How did you find them, David?’

The ones I had were fairly benign, they genuinely aimed to identify aspects of our craft requiring attention and improvement. By observing my classroom teaching they helped me diagnose any problems I had.

They gave you glowing reports, didn’t they, David?

‘That’s true. I was deemed an outstanding teacher. Somebody up there must have liked me.’

‘I saw others as intruding policemen,’ said Dr. Ward, ‘always looking for someone to upbraid. They didn’t take to my anti-militarist ideas.

A negative judgment from them, speaking of inadequacy, could occasion consternation and drain the confidence of our students and parents. It could change the course of lives. Of course, we embrace entirely the need for a robust inspection and monitoring framework.’

‘If you don’t get looked over, you get overlooked, said David.’

‘True. And teachers do need to be held to account by the outcome of the inspection – but they require a regulator, not a boa constrictor. And who holds the inspectors to account? Do they have a particular hidden agenda.’

‘Seen from outside,’ I said, ‘it might seem that having a group of fellow professionals come round every few years to write up your performance and give it a grade, after reviewing your performance, is not such a big deal. Aren’t these men selected because of their ability to convey ideas and information most effectively.’

‘Good heavens no, Allan. There is an element of this but only too often these are men who are themselves only too happy to get out of classroom teaching. Many couldn’t do it to save their life. They may have more knowledge about behaviour and safeguarding than any subject area. Their function is to maintain conformity and uniformity in educational institutions. The inspection is an old concept in management.’

‘It sounds just like the army. Would you elaborate on this?’

‘The basic concept is that of autocratic management aimed at catching the workers red-handed; a fault-finding attitude in management, and a one-time fact-finding activity. It can be viewed as a process of checking other people’s work to ensure that bureaucratic regulations and procedures are followed and that loyalty to the higher authorities are maintained. This view of inspection largely overlooks the professional interests and needs of the teaching personnel.‘

‘So how do they judge efficiency?’

‘Inspection process conducted with this view in mind may not be effective in upgrading teaching and learning. It’s more often than not a time for putting on something of a show to impress. But it’s very effective at getting teaching personnel to toe the line.’

‘How could we improve on this?’

‘We should move the responsibility for judging teachers and shaping improvement strategies on to the staff, students and parents who use them and work in them.

‘Even parents?’ I queried

‘Yes, Parents can bring a lot to this process, drawing both on the knowledge they have of the their children and their experience of other organisations. Involving all parties would ensure that all viewpoints are equally included in a discussion about what is good, what is less good and – once a shared understanding has been reached on those points – what would make things even better. This approach would enable people to be completely open with their views, critical, appreciative or whatever else. The possibility of contributing to positive change would provide an incentive to thinking hard.’

‘I hope such a process comes about before I graduate’. I said.

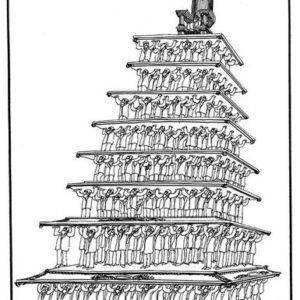

Don’t hold your breath. Our inspectoral system is highly bureaucratic and shares with all other aspects of the education bureaucracy, a top-down, hierarchical, and authoritarian character.

Regrettably it is well entrenched.’

‘And what was Nugget Coombs’ experience with the inspectorate?’

‘As a schoolteacher in rural Western Australia, Nugget horrified inspectors in the mid 1930s with his choice of classroom poetry. He taught his charges T.S. Eliot’s poem ‘The Wasteland’. ‘So much wastepaper!’ said one of his supervisors about this work. ‘This is not a book that should be set aside lightly. It should be flung with great force.’

Poets,prodigies, prophets and prodigal sons.

‘What is it about these works that raised the inspectors’ hackles?’

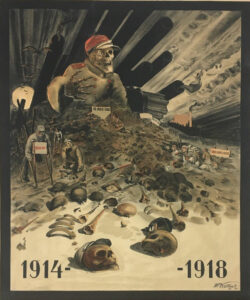

‘They deal with the general feeling of disillusionment and disgust of the period after World War One. The ‘Great War’, he said contemptuously.

‘He was part of the Lost Generation, wasn’t he?’, I asked.

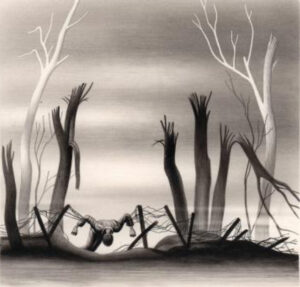

‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘though I prefer to call them ‘The Battered Generation’.’ He felt part of that flower of artistic youth who escaped being mowed down or gassed in World War I.

A good many of them were rebuilding their lives after being pitchforked into combat and suffering the horrors of war.

For them the idea that if you acted virtuously, good things would happen, went up in smoke forever.

Unlike your generation they missed the civilizing influences that young men usually have between the ages of 18 and 25.’

‘Weren’t young men from the ruling class able to escape being drafted?’

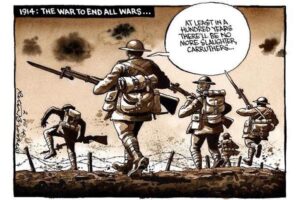

‘Unlike those of today and previously, they were expected to lead. In the years immediately after this ‘war to end all wars’, while others of the gilded youth wallowed in the decadence and superficiality of the era, the more serious felt spiritually alienated.’

‘In what way? I asked.

“Stranded between two wars, they were characterized by lost values, lost belief in the idea of human progress. Their mood was one of emptiness, futility and despair leading to hedonism.’

‘This is the aimlessness described by F. Scott Fitzgerald in ‘This Side of Paradise’, said David. He writes of a generation that found “all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.”

‘Coming into the war late,’ I said, they surely weren’t as devastated in the same numbers as the English and Europeans. Couldn’t they have just come back, buy some land, settle down in a quiet little town and forget about everything.’

‘The Americans in this group found their country a great place to go into some area of business but one they considered hopelessly provincial and emotionally barren. They all expressed a highly vocal rebellion against established social, sexual, and aesthetic conventions and a vigorous attempt to establish new values.

‘How did they go about this?’

Reticent about moving into a settled peacetime life, some were determined to raise a hue and cry. Intent on making a new art, they flocked to Greenwich Village, Chicago, and San Francisco.’

‘It sounds like that’s happening all over again. What about the rest?’

‘Others packed up their bags and went to cosmopolitan Europe, more open to less socially restrictive lifestyles and more experimental literature. While most relocated to Paris as expatriates, Eliot took up permanent domicile in London.’

‘Did they work together in any collective way in their self-imposed exile from the American mainstream? How was their work affected?’’

‘This group of American literary notables often had social connections with one another, even meeting to critique one another’s work, building a new literature, impressive in the glittering 1920s and the years that followed. Romantic clichés were abandoned for extreme realism or for complex symbolism and created myth. Language grew so frank that there were bitter quarrels over censorship. The influences of new psychology and of Marxian social theory were also very strong.

Out of this highly active boiling of new ideas and new forms came writers of recognizable stature in the world, among them Ernest Hemingway, doing away with the florid prose of the 19th century Victorian era, replacing it with a lean, clear one based on action, and in poetry T.S. Eliot, sharing a distaste for grandiose patriotic war manifestos.

‘Of course,’ said Dr. Ward, ‘Nugget’s inspectors, wanting to hear about the love of a sunburnt country, a land of sweeping plains didn’t go for this… To say nothing of Nugget’s inclusion of the trio of political poets and prophets inspired by the artistic principles of Eliot: W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and C. Day Lewis who emerged out of the Oxford scene. With all their differences notwithstanding, they tended to be lumped together as the Oxford Group. From backgrounds in elitist schools and coming of literary age in one of Britain’s most prestigious universities, they rejected the traditional poetic forms favoured by the Victorians. Rather they concentrated on themes of social injustice, protest and the class struggle. For them writing became a form of action. Little of the opprobrium young Nugget had incurred from these stern scrutineers would have derived from the actual poetry – the pettifogging inspectors probably didn’t have a clue about it – and would have dismissed it as overly convoluted and delphic, as much of Eliot’s work was. These poets were suspect because of their political temper.

‘As in the case of Pearl Buck,’ I said.

‘The inspectors must have seen red when they saw the names, Spender and Day-Lewis, card-carrying members of the Communist Party. Like Nugget they had counted Karl Marx in among their influences. Spender and Auden had been involved in reportage and drumroll for the war against Franco.

Spender had written a eulogy to the 1934 socialist uprising in Vienna and an anti-fascist drama “Trial of a Judge”.

On top of that, Spender and Auden were seen as ‘iffy’ because of their flaunting of the straitlaced sexual conventions they were expected to follow. Auden’s percolating homosexual tendencies bubbled up when he was a pupil. Allusions to this homoeroticism do occur through his writings. The inspectors must have feared that these poems would sway young impressionable minds, ignite an outbreak of bloody rebellion and perverse licentiousness …

“… leading to a juvenile Red Gomorrah”. I commented, presaging elements of Lindsay Anderson’s scenario “If”.

“To what extent people’s behaviour – particularly that of the impressionable youth – can be swayed by their reading is a perennial issue in education,” Dr. Ward replied. “Literature resonates with the experiences of each individual differently and brings out certain tendencies in some while leaving others unaffected. It depends on what one is predisposed towards. Young Auden’s inclinations – being innate – were most likely brought on early as much by the repressiveness of the boys’ public school he attended as by any book he got his hands on. The school encouraged informing and discouraged any discussion of personal development other than the straight and narrow. His first love grew in an environment of furtive loneliness.

The same goes for the political consciousness raised by these poets. In his hands Nugget’s students may have become more critical and belabouring issues but hardly likely to become violent. In point of fact, allowing them discussion of the widest range of ideas is the safest approach for any democracy wanting to win the unflagging fealty of its citizens. Driving literature considered subversive underground only reinforces any critical message it may have. All truth will out given time’, he said, excusing himself to get a cup of tea.

“Wasn’t it highly unlikely that such privileged young men from the ruling class elite joined the Communist Party, an organization avowedly claiming to smash class rule or became fellow travellers?” I asked of David.

“Once again Russel, would be better able to answer that question. He has a Masters Degree in Modern English Poetry. His thesis is about the Modernist poets and their votaries. It deals with Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot and W. H Auden.

Auden’s chunky feature as captured by Cecil Beaton were familiar to me.

He’s a mine of information about Communism.

Back in his seat, this is the account Russel gave of the politicisation of these poetic prodigies.

“Socialism taps at all doors, Allan. Especially of those questioning a system they were trained to lead. Let me point out that a key element of the vanguard of social and political change is usually to be found in the cradle of the ruling elite, those who fear change the most. The future of a country depends on the development of the movement of students. In the case of these young intellectuals between the wars, their poetry grew out of the nature of the contemporary world and reacted upon and influenced the ideas and passions of their readers.

‘You’d imagine they were as far from deprivation as anyone could get,’ I said. ‘In a desert of misery, Oxbridge was an oasis of civilized comfort. They were guaranteed the keys to the kingdom. There was no visible cause for them to turn against society.’

‘These young English minds, as brilliant as their pedigrees, fired by youthful idealism, saw clearly that, as in the Great War, every man jack except those who could hide one way or the other would be drawn in.

They saw no alternative to taking the stand they did.

You have to be aware of the climate of the time, Allan. This was a period of expanding fears and ever more urgent political and social crises. The pace of the time itself, the sense of time passing and an end approaching gave a special quality to the Thirties. The public world pressed insistently on the private world. Britain, like the rest of Europe was in a parlous state following the war.

The Depression brought widespread unemployment and hardship. Fascism was on the march. Hitler had been appointed Chancellor. Many saw fascism, including the homegrown strain, as a sword of Damocles overhanging the liberal democracies of Europe. We watched in horror as the Spanish overture gave way to the much larger conflict into which the whole world would be dragged.

To many students at Oxbridge – privileged though they were – this was deeply troubling and unacceptable. It forced thoughtful people to think intensely national and international politics just as the war in Vietnam is doing a generation later. Witnessing the democracies stand by passively and do nothing while the Spanish Republic was destroyed by Hitler and Mussolini, they expected them to be too invertebrate to confront them. They, and myself, saw the Soviet Union – the only example of a socialist state in the world – as the one powerful enough to smite this menace.

‘So it wasn’t at all surprising that you, with some deep feelings of guilt, questioned the justification for such a state of affairs.’

‘On the contrary, it would have been surprising had any sensitive and informed young man coolly accepted his position as though by divine right. The Communists did not require secret recruiting sergeants; the economics of the time served the purpose quite well enough”.

“What were the ideas these poets took up in this process, Dr Ward?” I asked.

“Before we go on, just call me Russel,” he said.

‘Russel it is,’ I replied.

“Clearly situated on the Left, like many intellectuals of their generation,’ said Russel gathering his thoughts, ‘poets like Auden openly espoused the ideas of Marxism – with its clinical, astringent rundown of the class system – which had gained popularity in educated circles”.

“What happened to them, Russel?” I asked.

“They became disillusioned with doctrinaire Communism with its zigzag turns, u-turn manoeuvres, skulduggery and shifting alliances to gain control, people never knowing what it was going to come up with next. One minute it was all for a popular workers and farmers revolutionary government in Spain and the next it was arming forces to stop this and gain control, aiming to present a moderate face to the liberal democracies. The clincher was the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact between Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia which many on the left saw as a betrayal. From Stalin’s perspective, the lack of resolve of the parliamentary democracies to confront Hitler left him little choice.

Spender and Day-Lewis resigned from the party. Spender, refuting his past, called it ‘The God that Failed’. For others after the Second World War the final straw was the repression of the 1956 Hungarian Uprising and the ruthless tactics employed by Soviet intelligence agents.

A continuous line of idealists soured to politics”.

“So what was the fate of the Auden generation?” I asked. “Did they continue to pose a threat?”

“Come to think of it, they were more pink than deep red. They jumped ship quickly rather than staying in the party and opposing Stalinism. Heading into the maelstrom of war, the alliance of the Soviet Union and the parliamentary democracies tended to blur – even if only for the war’s duration – their major differences and facilitated the poets’ return to the fold. Highly articulate, well-connected, they knew the right thing to say and had entrees into the highest cliques.

The old boys’ club would bend over backwards to absorb their protest and co-opt them smoothly. Sounding like roosters taking credit for the dawn, they put this down to their own irreproachable forgiving reasonableness and reforming character. They institutionalised the rebellious tendencies of these ‘enfant-terribles’, giving them a set place in their scheme of things, rendering them harmless. They forgave their youthful indiscretions, placed fig leaves on them, seeing the error of their ways as something committed in the heat of the moment.’

‘So, in politics nothing is impossible.’

‘It’s not preserved in aspic. Today’s bogeymen can become tomorrow’s national treasures, albeit usually only after they have been rendered harmless. Like Nugget, these poets committed to the allied war effort,

Henceforth they would reach a level of their career at a peak and become liberalising pillars of the establishment.’

Pillar Talk.

“What about you, Russel? You were part of that generation. Are you a pillar of the establishment?” I asked this self-styled radical who would join me increasingly with David in our collegiate canteen to strike sparks off each other.

‘It was tremendously exciting for me as a young man passionately reading literature at that time to come across these challenging minds. I knew just how young Wordsworth felt growing up across the Channel in the early days of the French Revolution.

“Bliss was it to be in that dawn alive;

But to be young was very heaven!”

I quoted, the poem fresh in my mind.

“As for any pillar talk, I’m now more like a Pillar of Hercules” continued this historical oracle. “A port of entry guiding my students into the realm of the recondite. Mind you I’ve done all right for myself,” he went on cautiously, as if he were rather embarrassed by his status. “You might call it poetic justice. I’ve worked hard to get here and copped my share of flak on my fuselage. All par for the course.”

Take a Proper Gander.

‘I’m fascinated by how so much “cultural influence” can be allocated to such a small number of individuals to earn them the reductive catch-all title of The ‘Such And Such’ Generation or ‘Such and Such’ Group. How they can come to represent an entire period in time’, I told David.

’ Not all members of a generation experience the same early events in the same way, as race, ethnicity, gender, and social class also color our life. Each generation discovers itself and finds its own expression through the Promethean output of its most talented members. ‘Do you have any particular one in mind?’’, he asked. ‘Is it today’s ‘Love Generation’ with long haired hippy girls and guys in velvet pants with spangles, love beads and flowered shirts, eating macrobiotic food, traipsing around carefree .’

‘I’m interested in the so called ‘Angry Young Men’”, I replied.

‘Ah, the catchphrase applied by the popular press to that literary rat pack from unpromising places and unglamorous backgrounds. What did they do?’

‘They crashed the stuffy Establishment party in one generation, harried the citadels of culture, and brought their idioms, themes, and passions to the centre of British life. They undermined the warm, cosy and bumbling stereotype of British life that had been projected in the 50’s comedies.’

‘What was it about the state of affairs that fed their blinding anger and frustration?’

‘These were times when Britain being finally exposed to the very real limits of its power, the political elite was more concerned with international crises such as Suez, or with their own internal debates such as the one taking place in the Labour Party over the future of Clause Four of its constitution. Even Tony Benn gave little hint of any interest in everyday working-class issues. As for the Conservative Government of the day, the Prime Minister, Harold MacMillan was famously telling Britons that ‘You’ve never had it so good’. Many young people could discern no brave causes.’

‘What do you see as their achievement?’

‘They transformed the British heritage, working with the materials of their own backgrounds, the class system, tradition, and artistic convention to make new art. Working class origins and identity no longer needed to be cleaned up. They could be seen as meritorious in their own right.’

‘‘This is nothing new, you know. These writers took their place in a long line of writers who thrived in grit: Daniel Defoe, Charles Dickens, Bernard Shaw, D. H. Lawrence. Do you have any favourite amongst them?’

‘Above all others I’m partial to Alan Sillitoe, the grittiest latecomer. Keep in mind you need grit to make a pearl. I found his prizewinning stories, definitive of their genre, hard to put down’.

‘Why is that?’ David enquired.

“Like Pearl Buck’s, Alan’s stories are grounded in a particular place and time. Set in the industrial heartland of England they reflect the disintegrating social fabric of postwar England. The comfortable complacency and social harmony of the early nineteen-fifties had been exposed as an illusion.’

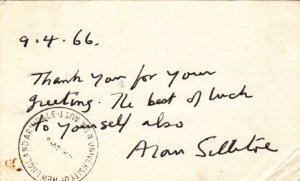

‘Have you made any comment to him?’

‘Alan appreciated my greeting him.

I told him he had injected fresh vigour into post-war literature with brash realistic portrayals of masculinity and defiant working class anti-heroes heretofore largely ignored in recent literature with stories riveting for their striking realism and raciness. I congratulated him for helping make their faithful adaptation into some gems of films.”

‘Frontrunners of the new wave in British cinema I believe,’ commented David.

‘Saturday Night and Sunday Morning and the ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner,’ I confirmed, ‘the rebels portrayed by Albert Finney and Tom Courteney respectively. The former film is important for escaping the cloying banalities of Ealing studios, the simplistic celebration of the Second World War and the reassuring conceits and certainties that followed.’

‘Talk about the characters in these stories, Allan.’

‘The main characters in his early novels are usually poor people, rebellious individuals, young men from rows of brick houses and grubby homes, deprived of economic and social opportunities.

They generally are opposed to the established social order but are yet affected by consumerism and hedonism. ‘Saturday Night’, a seminal novel of the period, conveys the attitudes and situation of a young factory worker, Arthur Seaton, charting a year in the life of this rude, abrasive and amoral young labourer who lives for the weekends, slugging down beer and looking for a bit of slap and tickle. This was the time of the week he thinks about taking a wife. The only question is, ‘From whom?’

His foreman says he must be a Communist, which Arthur accepts without knowing much about. Or caring about.

Alan describes Saturday night for this rapscallion as ‘the best and bingiest glad-time of the week, one of the fifty two holidays in the slow turning big wheel of the year, a violent preamble to a violent Sabbath’. Inevitably that roving glad-eyed rooster is faced with the end of this misspent youthful philandering. Wild oats sown in wasted daze could bring an unwelcome crop-being tied tied down with squalling brats as his missus dropped another. The three-timing Arthur looks doomed to knuckle under and for all his bravado he sees no other life but the humdrum one he was born into. Getting conjugal with a complacent ‘nice’ girl from his own neighbourhood only sealed his fate.

‘Arthur doesn’t sound like the kind of guy you’d care to cross,’ said David. Flinty and self-possessed. Does he have any redeeming features?’ he asked.

‘His saving grace is his honesty,’ I replied ‘It helps you overlook his off-putting traits. He flaunts his motto:’ ‘I’m out for a good time. All the rest is propaganda!’ While life has dealt him a lousy hand and his horizons are limited, he’s determined to make the most of what lies within them. Smarter than he looks, he knows what he wants and is sharp enough to get it. He has worked out on point the right degree of give and take he needs to make in order to live the kind of life he wants to live. He drinks hard, plays hard but works hard. He seldom feels sorry for himself and has a wise eye for the world. At one point, looking about him, he comments: ‘Nobody’s satisfied with what they’ve got, if you ask me.’’

‘What about his other stories?’ asked David.

‘In the title story of ‘The Loneliness of the Distant Runner’, the narrator is a young reform school inmate. This boy who gets his back up finds a kind of freedom in the isolation of distance running. The written sentences, rhythmic and breathless, read like miles and miles of evenly-paced running, taking you along with him. When the Governor backs him in a cross-country race we are party to the internal dialogue on his reasons for running and his ideas of what victory really entails. The borstal boy shows his appreciation for his gift being patronized. When the time for the race arrives, he declines the offered chance to abscond on his dawn solo runs and exacts the far subtler payback. He deliberately loses in order to spite and take down his guardians, to show his defiance of authority.’

‘Some critics found found this authenticity too confronting, I’m told. Sillitoe has often shown authority figures as inherently ignorant and ready to be manipulated by the lower classes. In making the film version, Tony Richardson drew upon the emerging youth culture as in ‘Saturday Night…’ in which Sillitoe’s use of vernacular was toned down and the successful abortion was changed so as to come up dry. One script reader found the screenplay rather risky. Let me read to you what he had to say,’ I said picking up the report from The Sydney Morning Herald. “But this story is very blatant and trying Communist propaganda, and particularly worrying for us because the hero is a thief and is held up to the admiration of young thuggish airheads. If leading citizens of Nottingham didn’t like Saturday Night because they thought the hero was not a good representative of that city, I don’t know what they will say about this epic.”

‘What Alan had to say was that likeminded attempts to censor his work smacked themselves of Soviet heavyhandedness in deciding what writers could and couldn’t say. How say you David ?’ I asked .

‘I say that any roughness or rudeness emanating from these ‘bad’ representatives is far outweighed by their economic contribution to society whether they be in Nottingham or Sydney. Some say all these proletarian lads want to do is drink and let their hair down, but don’t all members of the drinking class have something in common?’ he said as a familiar bawdy, glugging sound drifted in from down the corridor. Someone new had been singled out in the latest boozing match.

‘Here’s to Proudy, he’s true blue,

he’s a piss-pot through and through,

he’s a bastard, so they say,

He tried to drink it down, but it went the other way

Drink it down, down, down.’

This chug-a-lug chant continued till Proudy had finished gulping down his beer. When he had given full throttle to the bottle and downed it all they followed the skolling by trolling—

“Hooray to Proudy, Hooray at last! Hooray to Proudy, He’s a horses arse!” Such rituals could go on well after the law of diminishing marginal utility had set in.

The test was ‘you’re not drunk if you can lie on the floor without hanging on’.

‘Does a man good to cut loose once in a while,’ said Proudy.

‘You could do with being tied up once in a while.’

‘As for the more anti- social proletarian elements,’ said David, continuing, ‘we have to see things through their eyes and understand them. Louts and criminals come from all layers of society. It is less forgivable when they come from the ranks of the privileged’.