The Luck of the Irish

‘Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it for religious conviction.’

Blaise Pascal

Over my years in London, I made periodic trips to coastal France and the Low Countries in order to get my passport stamped upon re-entry. This guaranteed me the right of residency. My first long excursion was a tour of the Emerald Isle for one month in February 1971.

I was after exploring the social and political landscape as well as taking in some of the rural beauty for which Ireland is famous. As a treat to myself, on my pat malone, I rented a car and stayed in bed and breakfast guesthouses mainly in Dublin and Belfast.

Dublin proved very appealing. Unlike the huge sprawl of labyrinthine London, it was small, accessible and eminently walkable. Its rich architecture. lending elegance to wide streets and spacious squares, convinced me to enquire about teaching possibilities. Unfortunately for me, all teachers had to speak Gaelic so that avenue of interest was ruled out. I checked out church records of marriages to trace my father’s family. As I’ve mentioned earlier, I’m not very good at drawing. It turned out my great grandparents had married just before records began to be kept. Finding out more would have involved shelling out fees for professional genealogical research so, my ancestral spirits being located everywhere, I left it at that. My interest in family ties was nowhere as fervid as that of others on the island where one’s life could depend on them.

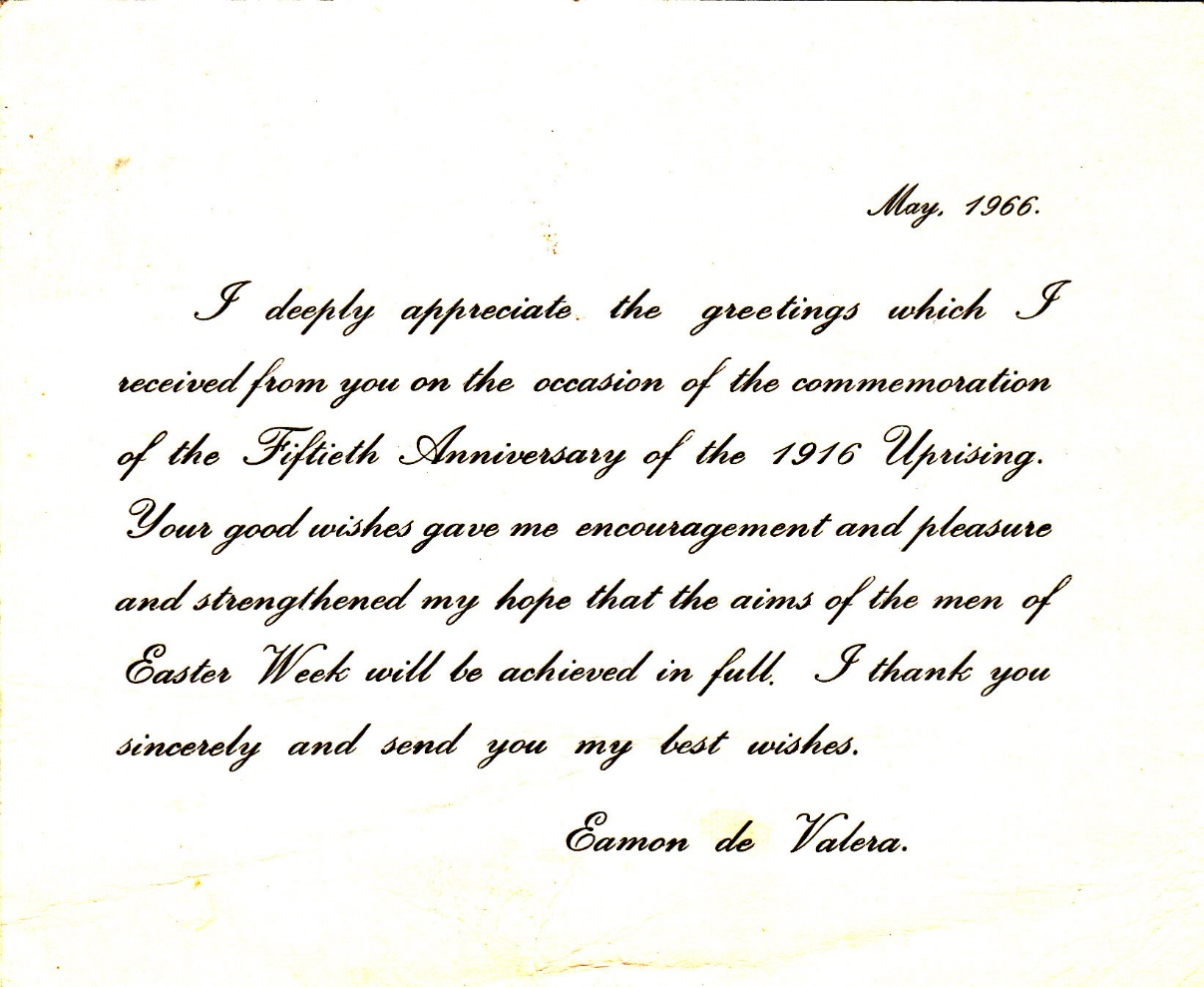

My journey kicked off with a visit to the Garden of Remembrance, dedicated to the memory of those who had fought for Irish independence. The Garden was opened in 1966 by President de Valera on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising.

Eamon de Valera was a leader of the uprising begun by Irish republicans on Easter Monday 1916 that crashed and burned. He was a commandant of the Dublin Brigade of the Irish volunteers. Fighting raged for a week before the rebels went down to the British troops. The British executed 15 republican leaders after the rebellion. De Valera was condemned to death but this was commuted to life at His Majesty’s pleasure. At first, the Easter uprising received little support from Ireland’s people, but the executions created great sympathy for the republican movement.

The stone wall of the monument in the Garden features a poem expressing the hopes and sorrows of the people, free from censorship. This was the first of a number of walls that would arrest my attention on this journey.

The Garden marks the spot where several leaders of the Rising were held overnight before being taken to Kilmainham jail. I retraced their journey going on a guided tour of the prison which is an important symbol in the difficult and protracted independence struggle of the Irish. Dates figure prominently in the Irish psyche. De Valera deeply appreciated my greetings and that of others on the commemoration of the Fiftieth Anniversary.

He told me and others my good wishes to him concerning this gave him ‘encouragement and pleasure’ and strengthened his hope that the aims of the men of Easter Week would be achieved in full.

This was for a united Ireland, free from the shackles of British rule.

Others, viewing the rebellion as treacherous, not heroic, were less celebratory. No balloons and definitely no party games. The response of the extreme loyalist paramilitary grouping, the Ulster Volunteer Force perceived the Anniversary as a revival of the Irish Republican Army.

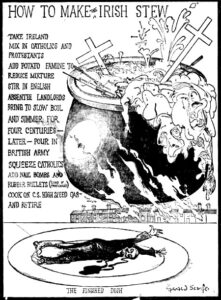

To mark the occasion these hard men carried out three sectarian murders, an event that foreshadowed the second instalment of The Troubles that racked Ireland in the Twentieth Century. Like the embers in a peat fire the Irish conflict had not died out. It would smoulder and flare.

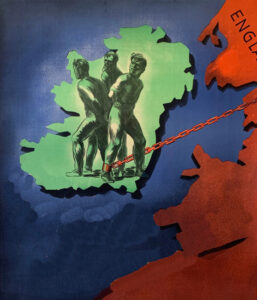

At the heart of the earlier Troubles was the question of the future of the British province in the North where the loyalist Protestants-descended from Scottish settlers, born and bred of empire- were a majority. The Civil War was fought between republicans over whether to reach a compromise and allow the North to remain part of the United Kingdom or to reject any continued links. De Valera led the rejectionist forces which were all up.

Before heading for Belfast in a hire car, I had to find the best route. Not like the one taken by the taxidriver who’d brought me into Dublin. He must have thought I’d asked for Tipperary. He took the long way.

The former stream of traffic from south to north had turned to a dribble. Very few people from Eire ever ventured along the highways and byways going to Belfast or asked the way. On the outskirts of Dublin I drew up beside a man cutting the hedge and enquired,

“Could you tell me the way to Belfast, please?”

He stopped and wiped his brow.

“Certainly, sor. C’mere till I tell ya. If ya’re headed to Belfast this fine day, take the first road to the left? No still that wouldn’t do? Drive on for about four miles then turn left at the crossroads? No, come to think of it, that wouldn’t do either.”

He scratched his head thoughtfully

‘You know, sor, if I was going to Belfast I wouldn’t start from here at all.’

‘Then why did you mention those turns at all?’

‘Who’s giving these directions, me or you?’

‘Have you lived here all your life? I asked him.

‘Not yet.’

I then ducked into a local pub and asked the barman the quickest way to get there.

He said, ‘Are you on foot or in a car?’

I replied, ‘In a car.’

He answered without hesitation giving me his learned advice, ‘That’s the quickest way, to be sure.’

Heading north with my new road map, I took the long way through the wilds, along narrow winding back roads, twisting little lanes where the overhanging boughs whipped the windscreen, where you could still drive for hours without passing another car. Over hillways, up and down, myrtle green and bracken brown. I passed scenes that seems torn from picture postcards: lush yet flinty hardscrabble farmlands carved by hedgerows, granite walls and crooked streams, sweet green meadows, ruins of medieval churches, cottages with thatched roofs, piles of peat alongside.

Men with red faces and flat caps stood around talking about who knows what – because theirs’ is not a language that outsiders can understand – but the chances were it’s sheep, because that’s all there was to talk about round there. These were all quiet reminders of the rural landscape so fiercely preserved by De Valera.

I pulled up alongside a small paddock where an elderly farmer was upright, tending to his crop. By the state of him he looked to have spent an entire life among farm animals, manure and straw. Foraging around the ground was a pig, a three legged pig. Keen to add to my agricultural knowledge, I called out,

‘Hello there, it’s a grand day. And what are you cultivating?’

He replied, ‘Begorrah I’m growing high yield protein packed potatoes. I’m after planting a new lot. My aim is to win the Nobel Prize.’

‘Are you serious?’ I replied, wondering if this was just another Irish joke.

‘Deadly. Why not, young man’, he said with a smile, ‘as anyone can see, I’m out standing in my field.’

“How much land do you have here if I might ask?”

“About two acres” the farmer replied the farmer. Nothing as big as the farms you have in Australia, I suppose.’.

“You know back home it takes some land owners a day to drive around their holdings. ‘

“Aye”, said the farmer ” I once had a car like that.”

‘Your work looks very hard. Do you get any help?’

‘ ‘Knuckles’ here helps me’, he said bending down to rub his tummy. ‘He sniffs out the underground tubers. These are no ordinary potatoes and ‘Knuckles’ is no ordinary pig. He’s one of the family with his own room. He demolishes any food scraps. He’s a great guard pig and squeals loudly when strangers come at night. He’s on fire rooting for worms, digging, scratching, loosening the soil, breaking up the sods and adding in his own fertilizer.’

‘Well, that truly is one remarkable pig. But tell me, how did he come to have only three legs?’

‘That’s obvious isn’t it ? A pig this quare, you don’t eat all at once.’

‘I understand how he ploughs the soil. But he can’t cover your whole plot. How do you manage to spade the lot? Does your family help you?

‘Sadly my son, the only person who can really help me, is in Crumlin Road Prison, under British detention.’

‘Well he can’t help you much , can he?’

‘He does what he can. I wrote a letter to him and mentioned my difficulty digging the soil by myself.

Shortly, I received this reply, “For heavens sake Daidí, don’t dig up that lot. That’s where I buried the Kalashnikovs.’

The next morning, at the crack of dawn, a dozen British soldiers showed up and dug up the entire plot, without finding any guns. They made a real pigs mickey of it. I wrote another note to my boy telling him what happened, and asking him what to do next. Having successfully pulled a stroke, his reply was: ‘Now plant your potatoes, Daidí. It’s the best I could do from here.’

‘My boy gave the Brits false information. He’s so clever.’

‘He didn’t lick that off the ground.’

In coming to Belfast, the most violent city in Europe at the time, I felt better equipped and placed than most to read this latest instalment. The prejudices and quarrels I would encounter would be I felt, more comprehensible and less distant, to me, having grown up in a society where there were fewer vestiges of these. It was like going into Australia’s recent past to some extent. Moreover, as an Australian I was able to move around better than most, once people knew where I was from. Many had relatives ‘Down Under’. In this tourist wilderness I was a welcome visitor.

At the commodious bed and breakfast establishment I stayed at, wanting to get moving about early, I asked for a wake up call.’

‘Just watch your step in some of our dodgy ‘No Go’ areas. Let us know your itinerary beforehand.’

Staying in that leafy middle class area close to the fine Victorian city centre, I saw little evidence of the hurry-scurry that you read about so much. Ostensibly there were no great differences between people from both religious communities. They spoke the same language, ate the same food and barracked for the same English football teams. Bringing to mind Freud’s notion of The Narcissism of Small differences’ the variances were small but blown up by mischief makers to become an enormous thing.

Anyway like mine hosts, most residents went on with their business as usual with little or no inconvenience. All too often this area was where the only real mixing was done. ‘The only way the rest manage to get on is by ignoring each other and by recognizing that there are physical boundaries’, said the proprietor.

Regrettably these boundaries applied to his own B&B. I was awoken in the morning by a knock at the door and this attractive maid saying, ‘Good morning, Mr. Davis, did you sleep well?

She had a body that seemed to say: ‘Hey! Look at this!’ She was the kind of woman that made you want to drop to your knees, and thank God you were a man!

I replied, ‘I don’t believe I made any mistakes.’ Then realising I was still in just my underpants, I said, ‘Please excuse me Miss while I get into something less comfortable.’ Quickly throwing on the rest of my gear I returned to find out the reason for this appearance.

‘I’ve come to turn down your bed,’ she said.

‘Well, many women have in the past. Why should you be any different?’

Trying to explain why, she offered the following, ‘I’ve got a boyfriend.’

I said, ‘I’ve got several. But let’s keep it simple. Let’s keep boyfriends out of it.’

It was a good try at least. And not my last. As I picked up my bags later before leaving, this maid/cum receptionist asked me, ‘Have you got everything?’

‘I’m afraid you missed the opportunity to find out first hand, I replied mock heroically. ’Let me just say I’ve never had any complaints.’

One of the favourite haunts for people to go and find some craic was the quaint ‘Bittles Bar’, formerly known as ‘The Shakespeare’. The hostelry became known for its literary associations, with a portrait gallery of Irish writers, including Shaw, Joyce and Beckett whose names covered the world. Sipping my pint, I mulled over a comment that Beckett had made while teaching at Campbell College, a prestigious grammar school. On being told by the headmaster that his pupils were the cream of Ulster society, Beckett’s riposte was “yes they are, rich and thick”. I would bear these qualities in mind when sketching out my judgment of this society.

Cruising along Belfast’s thoroughfares and side streets, I got an overall picture of the city and its haphazard layout. The time came to leave the car behind and do some necessary footwork. Checkpoints and road blocks had led me to being stopped and questioned by the military for the second time in as many hours. The first time I was surrounded by two military vehicles full of British soldiers. “I want you on the ground before I count three!” barked their leader, before easing off.

They wanted to know why I was frequently stopping to look at places I found of interest. Driving a car registered in the Irish Republic undoubtedly caught their attention. While the military were generally courteous, and helped me with my bearings, their inquisitiveness cramped my style. Understandably they wanted visitors to keep clear of the areas they were trying to contain. There was obviously more happening than was meeting my eye, so I directed mine to the better known trouble spots.

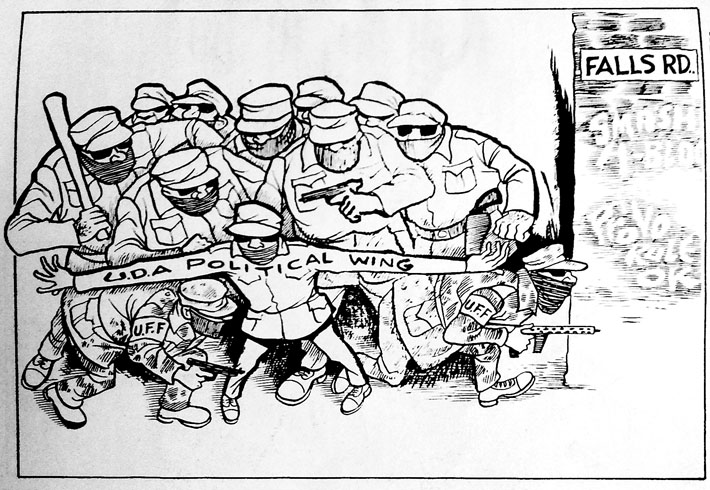

The low-income council housing estates and working class neighbourhoods were at the epicentre of the conflict. Its residents had never been enrolled in schools for the well-heeled. These estates had no gamekeepers. Of scantier means, these Hibernian proletarians certainly learned how to put the boot in. Their street wise ways would leave a strong imprint on my memory.

Prowling in and out of back streets on Shank’s pony, I found it easy to strike up conversations with people by asking for directions. Through them, I learned the different community boundaries, street by street. The sectarian violence was leading to what some call “ethnic cleansing,” with the province’s two main groups retreating into homogeneous, tribal enclaves. ‘That street over there is a Nationalist, but that on over there is staunchly Loyalist”.

From the locals I learned to interpret the visual shorthand that said so much about those asserting their control of the area.

The more conspicuous were the Union Jacks and paramilitary flags fluttering about proudly in the front of homes. I trod carefully along the cracked pavements marked with paintings paying homage to fallen heroes and messages of hate and peace to show that I had consideration for their authors – whether I did or not.

This is where the eye-catching murals that had just started to take off in a big way were sited. People were much more likely to accept paintings and slogans on gable ends or terrace and estate walls if they didn’t actually own them themselves.

As cultural emblems, boundary markers and political art, murals and slogans provided a direct comment on and a reflection of prevailing social conditions, particularly the republican ones. ‘Brits Out’ was the most frequent demand in the Catholic neighbourhoods. ‘The Curse of Cromwell be on you, Protestant Bastards’, was a traditional utterance. Loyalists rejoindered with such watchwords as “The Shankill Will Remain British Forever. No Surrender. No Sellout.”

Loyalist murals tended to depict historical scenes such as the arrival of Cromwell when he carried out persecution of Catholic practices, massacres and dispossession of Irish landowners in favour of loyalist immigrants, and the Glorious Revolution when William of Orange consolidated the Protestant Ascendancy and denied Catholics such rights as being able to vote and to hold military commissions. These sanguinary and divisive campaigns laid the groundwork for the ongoing cycles of communal strife that would plague the island.

Whatever I thought about the content of these various forms of expression, one thing was for sure – each was a strong pledge of commitment to one particular community which the community reciprocated. No one dared to remove them without incurring the collective wrath.

There is nothing like where the hops and barley flow to reveal the character of a people and a city. It took me several visits to the pub I selected along the Falls Road before the patrons relaxed their guard and saw their way clear to talk to me in a heartfelt way about The Troubles and what it meant to their lives.

It meant that they always had to be vigilant when meeting strangers such as myself in case I was a spy for a paramilitary group of a different complexion or the security forces .

It meant that they had to keep a lid on that warmth and acerbic humour for which they are renowned.

One drinker lifted this briefly when I asked why there was no billiards table or darts board for entertainment. ‘These games are considered too slow,’ he explained. ‘What we play now is much faster. It’s ‘Pass the parcel’. It gets very fast in winter, there’s that many layers.’

As we were talking, the newsreader delivered the following headline on the television above the bar, ‘The Troubles returned to Northern Ireland today. Two RUC officers were killed when their car ran off the road and hit a tree.’

The drinker said, ‘The IRA have already issued a statement. They planted it.’

‘They always claim responsibility.’.

‘Even when they eliminate those they suspect are traitors in their ranks. One of my neighbours Fergus, a Provo, comes to mind. All teary eyed Provo, he approached his priest after mass recently.

The priest said: “So, my son, out with it, what’s riling you?’

Fergus replied: ‘Oh, Father, I’ve terrible news. My comrade Brian passed away last week.’

The priest said: “Oh, that’s so sad. Such a young man. Did he leave his spiritual estate in order? Did he have any last requests?”

‘Certainly father,’ he replied. ‘He said: “Please, Fergus, put down that damn gun.’

Over and over, I heard the same string of grievances from individuals within the nationalist camp. “Faith, don’t be thinking we’ve got no cause for giving out. Steady well paid jobs are scarce for young Catholic men. The Prots bitch about fewer jobs in the linen game and shipbuilding, but you’ve got twice as much chance of being unemployed if you’re a Catholic”.

“Jaysus, if you’re a Catholic You don’t stand an earthly of getting a house at the same time”.

“All right, there’s twice as many of them as there are of us. Yet ninety percent of the Royal Ulster Constabulary are Presbyterians. As for the B Specials, the paramilitary reservists, all are. Guess who’s got the highest percentage of prisoners? How fair is that?”

My public house snug commanded a wide fly on the wall view of comings and goings along a stretch of the Falls Road.

‘What will it be?’ asked the barman.’

‘My father said I never should miss my Guinness. As if I would.’

Observing the passing parade, I saw what appeared to be a figure in the distance scuttling down a drainpipe. Soon a young man came towards the pub, pushing a pram hurriedly past a row of ratty terraced houses along the way. Just then the barman, brought me my drink and greeted me: ‘What’s the story?’

‘It’s good to see families are still being raised’, I replied.

Looking out the window at the pram pusher disappearing up the street, he said ‘Dis jimbo is no da. He’s just a big kid.’

Surely there’s a bit of illegality going on here,’

‘That’s right, the scrapyard owners passively encourage minors to ‘liberate’ other people’s property because they can’t be punished too harshly if the cops catch the kids thieving, or if somebody has an accident. What your man’s after raising is lead. He peels back long strips of lead held by nails on the roofs of empty houses, hauls it in the pram and sells it for scrap metal along with discarded appliances and cookware. Dere’s no honest jobs around here.’

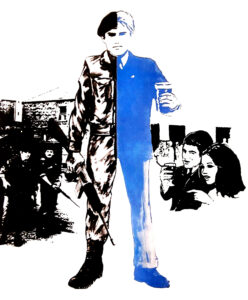

This ringside seat then afforded me a close up of a leading player in the daily drama being enacted on Belfast’s streets. It was heralded by the sound of metal, the lids of rubbish bin lids being beaten rhythmically against the wall. This was the housewives alarum of its approach. It made its appearance stealthily, scanning all round, twitchy eyes darting to every window, every doorway, every corner. With six heads and six pairs of eyes, this armoured shapeshifting Hydra was able to split into two, switch its component parts around, and to reconstitute itself. Its makeup was a smearing of camouflage paint on face and the back of hands. Like the Greek mythological creature this standard six man British Army patrol would prove difficult to extirpate.

Staking out along the street, well spread, three on each side, no bunching up, rifles poised, the detachment kept a tightly calculated spacing between each. Its grim countenance contrasted surreally with that of the children gambolling blithely about on the footpath. Others, more aware of their presence were less gladsome: ‘Away home, youse British pigs!’ yelled one, irate woman, a tattered shawl on her head, defending her doorstep, ‘Stop acting the maggot.”

I could make out one little old lady at a window holding up her hand to them. Its outline was that of a gun indicating that they would be shot. As they passed my pub’s window, they approached a junction several doors away. They took their lives in their hands crossing the junction as there was exposure from every direction. The point men scooched low to create a smaller target, the middle men approached them, tail-end Charlies took cover facing the rear.

Taking it in turns, each pair dashed to the other side of the junction while the others covered all angles aggressively. On signal, a hand placed on top of the head indicated to move on. All carefully rehearsed smooth fast movements to prevent a crack sniper getting a bead on them. Especially vulnerable were the tail end Charlies, who could be picked off after the others had crossed. Another menace to consider in this urban guerrilla war was the cowboy attack in which a machine gun would be held and fired from around a corner, the shooter being directed by a lookout.

Mindful that their every move was possibly being observed, the squaddies began their wary advance along the row of terraced houses. They were aware they might instantaneously have to take life and death decisions.

This street led on to a skid row which ran through the Green and Orange zones, composed of forbidding, fleabag, jerry built houses ridden by the holes of bullets and the scars of petrol bombs. Whoever said ‘as safe as houses’ had obviously never been here. It looked like the set for a Jack the Ripper film with narrow unlit arches between the houses. and the constant drip of water from something leaky somewhere. These rotting, foetid abandoned properties above which the sky resembled an unwashed duvet. in which sunlight was little more than a rumour, were likely hiding places of any hit and run merchant. Their dank, draughty bricked up passageways were no obstacle to entry for the gunman but offered him protection. They could house booby traps unleashing thousands of wee jagged shreds of metal to rip flesh apart.

By way of introduction to these grungy derelicts, the Tommies had to negotiate the pebble dashed terrace houses. Moving slowly, they were gauging the likelihood of contact from the volume of sound. Too quiet spelled danger. From my snug seat I watched them take cover in the porchways, moving surreptitiously to the front doors to check if they were open. A slight nod of the head was enough to signal that the doors were closed, that the coast was clear. Open doors would have hinted at the distinct possibility of an ambush. A sharpshooter would have been able to move in and out of any of the houses at will once the occupants had got the message and made themselves scarce.

I said to the barman, ‘These trigger men must raise havoc amongst the troops. They must be invaluable to the IRA’.

‘It sees them as worth their weight in gold’, he insisted, ‘the Brits dread them, it forces them off the ground, but their activity is very dicey. One of the most wanted crack snipers had a narrow escape up on one those vacant houses just last week.

‘How would that have gone down amongst the faithful?’ I asked

‘This guy in particular, is an indisputable folk hero to the youth. Anyone who takes on the Brits and pins them down wins their respect. Without cover they’re clay pigeons. He’s seen as a paramilitary protector of Catholics.

‘It’s a terrible business this resort to sniping,’ I said. It’s so cold and premeditated, striking some mother’s son down this way.’

‘These things are not pleasant but some mother’s son has to do it. We’re hopelessly outnumbered. These mothers asked for it, not us. We’ve seen fathers and brothers of friends being killed in the streets and the feeling is, we all have to do something. We’re all in this together and we all have to do something.’

‘How do you deal with your conscience. You’re doing the same as your adversaries.’

‘The thing you have to remember, what you have to understand, is the mindset. Once you have signed up and joined the organisation, the group, your mind closes right down. It becomes only our story that matters. Not their story, the Protestants. It’s only my people that are being killed and who are suffering and who need looking after. Protestants being killed doesn’t enter your head.’

‘What attracts men particularly to such a life?’

‘They’re drawn by the motto. ‘One shot, one kill’. One sniper on overwatch can change the direction of the war with a bullet in the right place.’

‘That being?’

‘The best being the base of a man’s skull, that spot where the medulla meets the spine.’

‘Some of the young would fill his shoes when called, I guess.’

‘Lots of local lads have been up there on the rooftop studying the scene.’

‘Could I go up there to see by any chance?’

‘Mmm,’, he pondered, ‘why not. I’ll take you up there at the end of my shift if you don’t mind waiting. I trust you’re fit.’

‘I’d like to think so. I move fast. I’m down for it. You won’t have me around your neck. You don’t expect any trouble there now, do you?’

‘The odds are low. Lightning doesn’t strike twice in the one place. The Brits have lots of places to be taken by surprise in. They can’t cover them all.’

Later that afternoon we went up the laneway to our point of entry.

‘Let’s do this’, said the barman.

We shinned up a drainpipe and went in through a window. As I turned to survey the surroundings outside, he warned me: ‘Keep moving, someone might blow you a kiss!’

Up the stairs we went – gingerly, because only flimsy treads remained-and through the skylight.

‘This is what happened,’ he told me when we were up top, standing before a row of chimney pots.

‘After lying prone for hours at night behind this chimney stack, never taking his eye off the street below, he decided to risk a smoke. He got cocky. The Brits saw the flash in the darkness and the glint of his rifle. After placing a fag between his lips, he struck a match, took a whiff hurriedly and put out the light. Almost immediately, a bullet whizzed over his head. and flattened itself here, against the breastwork of the parapet of the roof. You can see the hole it made’, he said, putting a finger in it.

‘As he tried to clear off, he tripped over a pile of rolled up lead. A sharp corner of lead ripped open the side of his pants, making a deep gash in his thigh. There’s the trail of blood that trickled down his leg. He must have cursed to the heavens. Like others provos, he wasn’t impressed with whoever had left the lead, obviously expected to pick it up later. The roofs leak like a colander after being stripped, damaging the houses, and the strippers get in their way. Moreover sometimes they target the house of God.’

I said, ‘It’s doubly chancy working as a metal recycler on the roofs of Belfast.’

“They know the drill. If they don’t the Provos will remind them,’ the barman said, making a whirring sound with his tongue. To the knees of those who disappointed them, the IRA pointed the business end of a power tool.

‘I don’t suppose we can put a name on this marksman, can we. Does he have a nom de guerre?’

‘To keep matters simple, lets just call him Eamon,’ he replied, smiling, ‘cos that’s what he’s best at.’

Bonfire of the Insanities.

My ears pricked up when I heard the forecast – not of the weather but of one of the public shindies with which the blue light area was associated. They were kicked up at the weekend after workers had received their payment or dole. All it needed was an excuse to trigger things off. On this occasion, the grounds for the action was the burning down of one of the Orange Lodges which represented Protestant domination. The lodge was where Protestant loyalists would the following evening be preparing to celebrate July 12, to mark the defeat of the Catholic King James, by the Protestant William of Orange in 1690. The Protestants were out for their pound of flesh and the word spread that the crowd would form just behind the ‘peace line’, the stretch of razor wire that kept the twain apart.

The long twilight had faded into darkness. So here I was on a nippy, Friday night pea souper in Belfast about to witness a ritual that harked back to the Middle Ages. At a safe distance I stood watching one of the hundreds of fires topped with Irish and papal flags set alight at midnight, on July 11, Orangemen would march the following day to commemorate the date when forces loyal to the newly crowned Protestant king of England, routed the army of the deposed Catholic king in a river valley south of Belfast.

Set in motion by a roaring boozy handful of young swinging dicks milling about, a torch and pitchfork crowd quickly descended upon the line. The tartan scarves and flash of tartan they wore on their denim jackets told who they were. Goaded by blind hatred, all shouting over each other, they jeered at the Catholic residents across the way, calling them names, baying for their blood: ‘Hand us your Provo bastards. They’ll be dangling and swinging in the wind before we’re finished with them.’

The configuration of coloured lights turned on in the windows of the tower block gave a coded warning that the security forces had been alerted. To the accompanying sound of breaking glass and wailing sirens they set to hurling missiles and breaking up paving stones for ammunition. The names could never hurt but their sticks and stones certainly could.

This situation escalated rapidly and moved throughout the adjoining streets like wildfire. The riot police of the RUC had no difficulty homing in on the semi darkened street whose lights had been smashed. The hail of petrol bombs and blazing overturned cars was the all too familiar beacon. Piling out of their wire screened Land Rovers, a clutch of burly, lantern jawed officers waded into the crowd to establish a cordon. Solid avoirdupois.

Reading the Riot Act the chief constable bellowed: “What’s all this shouting in aid of, boys? Break it up now, you’ve had your jollies. Its time to shift yourselves. If any of you as much as looks sideways now, I’ll ‘ave you. On yer way. Go home”.

Pushing back, the heaving crowd dug its heels in. As the peelers came to close quarters with the more recalcitrant elements by the light of the hateful bonfire, their grappling struck me as some kind of ‘danse macabre’. The dancing would soon be to the roaring beat of the massive mobile cannons brought in by the Army who had just rolled in as back up.

Maybe if the security forces had just passed the hat around, these mean protesting Prots would have begun to shuffle off sooner.

Meanwhile the Catholics, the target of the assault, had high-tailed terrified out of their wits to their barricaded streets and into the safety of their homes. As if it couldn’t get any uglier a group of youths forced its way past troops, and managed to lob petrol bombs into several houses. The soldiers responded with flashballs and a sustained fusillade of rubber bullets. These sent the firebrands scattering to the four winds.

That was the extent of the ructions as far as I could see. I read the following day of the encounters that ensued in various locations during the night. During their flight, dispersing rioters had come up against groups of nationalist youths who were only too hot to trot when not outnumbered in the fray.

On “the Twelfth,” Northern Ireland’s official sectarian holiday, I took my place among Belfast spectators, many bedecked in Union Jack-patterned hats and sunglasses. There was clinking and glinting medals stuck to veterans’ chests, regimental berets worn by men with beer bellies in ill-fitting suits, smartly dressed poppy wearers, soldiers in full dress uniform and tourists.

I watched the assembly of Orangemen and their morning parade out of the gate to proceed provocatively past potentially hostile Catholic areas.

‘We are told that there are places in this country that are no-go areas. ‘Not in our backyard,’ they say. Well, we make our own no-go areas. And we don’t care what the rest of the world thinks,’ declared an Orange spokesman.’

Accompanied by so-called ‘kick the pope’ bands of fife and drum playing a mixture of Gospel and sectarian tunes, they marched beneath banners portraying the British crown atop an open Bible and canonized William as defender of their civil and religious liberty. At the head of the procession was the Lambeg drum. It’s massive oak frames emblazoned with colorful Protestant Orange Order emblems and other symbols of Ulster heritage, the ringing beat from the 45-lb. drums sounded like a church bell.

To any Catholics, the rhythmic beat pounded out on the goatskin heads was a war cry, its thunder as much a part of Protestant swagger as the flute bands, the uniformed Billy Boys, the dour men in bowler hats, their orange sashes framing stuffy, stiff dark suits, all regular with absence of variation. Clockwork Orangemen.

Whether Beckett’s takedown was a reference to the solidness or stolidness of the younger members of Ulster’s ruling elite, I wouldn’t bet on it. While he was in Portora Royal’s Rugby team, they were outweighed and outplayed by that of Campbell College. Like the sturdy policemen who would follow their directives, they always had a full belly. They weren’t asinine.

As sons of the captains and lieutenants of Ulster’s industry and commerce, they were obviously inheritors of an outstanding scientific and technical intelligence. Yet they also came into an ideology which allowed them to see their superiority as something innate. Their lot was to take on the self-assuredness and contentment of the privileged group inured to the privations and resentments suffered by others on their island.

To try and escape the climate of sectarian division was like trying to catch lighting in a bottle. Education was fissured along confessional lines. Even Beckett’s own school, once known as the ‘Eton of Ireland’, Portora Royal was affected by the tribal hatreds of Ulster. Because of my mixed background I had no instinctive bias against either camp. I saw differences as being political rather than religious. With regard to social matters such as pre-marital sex, homosexuality and censorship, some feared the edicts of the Catholic Church.

‘People should be free to think for themselves’, one drinker told me. ‘ It’s the individual’s right to decide for him or herself how they live. Take family planning. It is now quite lawful for a Catholic woman to avoid pregnancy by a resort to mathematics, though she is still forbidden to resort to physics or chemistry.

The papists claim the Lord of Hosts shall strike them down for each sperm that’s spilt in vain. Poppycock. I can wear a little holy hat over my old feller to prevent issue. I wear it on every conceivable occasion. I’m never never gonna do it without the fez on. And Protestantism doesn’t stop at the simple headware. Oh no! I can wear whatever doodah I want. I can wear a French Tickler if I want. Ribbed for her pleasure.’

His mate said, ‘If my missus and I want to split the blanket, or if a bun in the oven turns out a half-baked idea, we can always do something about it here. In the Republic if you want an abortion, there’s a twelve month waiting list. You’d have to drag us screaming and kicking to priests telling us what to do and what not to do. They even tell couples who want to control their births to keep the light on.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with making love with the light on… as long as the car door is closed.’

At the same time the views of some Protestants I heard were out of step with the more liberal mainland and were more consonant with those of their hardline Catholic adversaries. The hairdresser I went to had his salon opposite the labour exchange where the unemployed filed into.

‘They’re mostly Taigs,’ he said, waving his scissors around my head. ‘I’ve got nothing against them as such, mind you. It’s their religion I hate. Their church keeps them ignorant and on their knees, filling the bloody world up with bloody people they can’t afford to bloody feed. Their Church never made the great leap out of the Middle Ages.’

At the same time the views of some Protestants I heard were out of step with the more liberal mainland and were more consonant with those of their hardline Catholic adversaries. Such unionists rejected countless chances to create a non-sectarian constitution and a lasting political settlement. They saw sellout at the slightest hint of a compromise. They had a siege mentality negative construct, seeing conspiracies against Protestantism and the separate existence of their state everywhere.

Prominent among the hardliners was the Reverend Ian Paisley.

He would shoot down any attempts to bring peace, presenting this to his followers as a victory.

As for the British, coming to terms with the move to independence of the Irish proved inordinately knotty and protracted.

De Valera was the biggest hitch. With him around there could never be much agreement. Let’s trace his movements. In 1917 he was released in the general amnesty and was promptly elected as a Sinn Fein member of parliament. Thenceforth he headed both this movement and the Volunteers. His second arrest in 1918 might have paralyzed the cause. However the following year he made a dramatic run for it from Lincoln prison and went to the United States to raise money for the Irish cause. Upon his return to Ireland, de Valera led forces rejecting any continued links with Britain.

After their defeat in the ensuing civil war, de Valera built up his political forces and became Prime Minister and President several times. The 1937 Constitution which he drafted broke nearly all links with the British Crown and claimed jurisdiction over Northern Ireland. The bitter breach would affect the allied war effort.

Understandably, he rejected talks initiated by Spellman to secure Britain’s use of Irish ports for it’s ships. It affected De Valera’s better moral judgement. In his studied neutrality, he got carried away, paying condolences to the German Embassy on the death of Hitler, the dictator’s best career move to date.

The Constitution recognized the special position of the Roman Catholic Church. A secular one would have softened the stiff resistance of Northern Irish Protestants to Irish unification. This would have minimized fears of the edicts of the Catholic Church. Understandably, in light of the eventual revelations of clerical abuse.

People generally don’t fear others from difference ethnic or religious groups when they are a small minority. In a country where men are traditionally supposed to have an uncircumcised shamrock between their legs, Dublin has now had two Jewish mayors.

Its when ‘they’ reach a critical mass that people can feel threatened.

A message from de Vaera on behalf of Ireland rests on the lunar surface and states, ‘May God grant that the skill and courage which have enabled man to alight upon the Moon will enable him, also, to secure peace and happiness upon the Earth and avoid the danger of self-destruction.’

The next scenario of division and threat I would investigate was one where “they” had on the outside not just broken the habit, the “opium of the people”, but the very economic underpinnings of religion.