Most people think Great God will come from the sky

Take away ev’rything, and make ev’rybody feel high

But if you know what life is worth, you would look for yours on earth

And now you see the light, you stand up for right, yah

We’re sick and tired of your ism schism game

Die and go to heaven in Jesus’ name, Lord

We know when we understand

Almighty God is a living man.

Bob Marley.

I ran into something new in British schools.

The presence of large and growing numbers of black children.

I taught history by and by in two lower secondary schools – one at North Paddington and the other Isaac Newton.

I got on well with these adolescents who were, by a wide margin, from a West Indian background. These Jamaicans, Kittitians or Antiguans looked on me as a bit of a foreigner like themselves. Christened with such colourful names as Delroy, Winston and Nelson these youths were generally effervescent and jovial. On introducing myself, I clarified my surname by alluding to Sammy Davis Junior. Henceforward I was inevitably addressed as ‘Sammy’.

While socially disadvantaged, their exciting music with its rebellious overtones was the most popular form of cultural expression in their daily lives. It created a positive vibration that would connect them with their white classmates – and myself.

West London with its large Afro-Caribbean community was the natural point of entry for the thrust of reggae, the potent sound of Jamaica, onto the world scene.

This is where it gained a foothold. The first of its interpreters to gain wide popularity in the UK at this time was Jimmy Cliff for his starring turn and soundtrack for the 1972 cult classic ‘The Harder They Come’. The film exposed the searing poverty and violent class warfare of Jamaica to the world.

When exhorting them to listen to the widest range of beliefs, I referred to Jimmy Cliff speaking of the learning process as one of going through many doors and classrooms. His beliefs had evolved this way and my inference was that they should follow suit and take advantage of their time at school.

Adding to the anthology of songs of determination, resistance and faith was Bob Marley, who through his seething lyrics sought to indict slavery, colonialism and racism. Jimmy and Bob, like others of the new crop of Jamaican artists, had first-hand knowledge of the deprivations of their own ghettos. Bob was able to latch onto the social turbulence of the era and channel it into politically charged music. Through his socially observant work he combated political repression and championed racial unity.

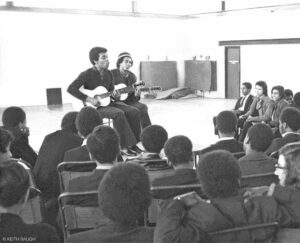

One day, the word spread throughout the school that Bob had visited a Peckham school along with Johnny Nash. My children were jealous and chatted excitedly about the concert.

‘Not only did those lucky blighters get treated to versions of Stir It Up and I Can See Clearly Now,’ said one of my students, ‘they got time off class.’

‘And after the show in the gym, these artists answered questions from the audience.’

One boy asked Johnny, ‘What is it like to be in a recording studio?’

‘What did he say about that?’

He replied that it is humbling to work with so many talented musicians, that you have to be focussed and well prepared and cannot afford to waste time.’

‘There you are, boys and girls, that’s something for you to keep in mind.’

‘Bob answered questions about his striped beanie tam. He laughed and took it off, letting those baby dreadlocks of his tucked under spring out.’

‘They’re part of his Rastafarian belief, aren’t they,’ I asked

‘Yes, like about reggae most people outside of the Caribbean scene are largely ignorant about it. They probably consider the sound rather lightweight.’

‘Well, his music certainly makes enough people happy.’

‘Not enough for the record business. Bob’s not happy about his prospects here. He complains that radio stations won’t play his songs. He’s fed up with our weather and can’t afford the plane fare back to Jamaica.’

‘I’m sure his strong personal spirituality will get him through his troubles,’ I said.

‘He should come and play for us here. We’d make so much clapping, foot stomping and cheering, the whole world would hear. We could help launch his career here in Britain. We already buy his records. If he came here all our friends and families would buy them. We’d give him lots of publicity, a wider exposure and get him into the top 40.’

The kids at Peckham must have really been impressed by their music.’

‘Not just by that. Bob showed off to them his second great talent.’

‘In a kickabout he astonished the students with his football skills.’

These kids and schoolgrounds looked exactly like the ones I knew.

Together these artists paved the way for my lessons, gaining me smooth entrée to the seat of my student’s attention. With a nod to their natty sense of fashion and desire to be seen as ‘cool’ I addressed them as “Rude boys and girls”, the term used in Jamaica. Before I knew it, I was tempering my own idiom with that of reggae, chiding them: ’Cease and sekkle!’, ‘Simmer down’, ‘Cool out’, ‘Ease up uno selves’ if they got a bit frisky, to give ‘wailing’ a rest if any loafers, laggards, scallywags and skivers slouched, grouched or backchatted about the discipline I insisted on, and to ‘tighten up’ as a response. ‘No slippin’, no slidin’, no bumpin’, no borin’, no fussin’, no fightin’; I warned them, dropping my ‘g’s left, right and centre.

‘So, fee-fi-fo-fum, look out baby, ’cause here he comes,’ I overheard Delroy say one day as I approached, taking on the persona of one of the Temptations lead singers. He spread the word: ‘Mr. Davis is on his way.’

‘Here I am, you Iucky peopIe, I greeted them. ‘Today’s topic will be tricky but we can’t be picky. So get down now and don’t get frisky or risky.’

As the class settled down to pay attention, Delroy kept sweet talking his girlfriend Marcia in a gritty tone:

‘If you just put your hand in mine

We’re gonna leave all your troubles behind

keep on walkin’ and don’t look back.’

‘What’re you on about, Delroy?’

‘True love is worth the heartbreak and failures it takes to reach it!’

‘Do you know this from experience, Mr. Mention?’

‘O Marcia, Mi lub yu kyaan done. Let’s keep bench an batty.’

‘Yu too likky-likky. Don’t me ever catch you in a lie, or you’re for it. Listen to Louisa Mark. She knows how to convey heartbreak.’

‘And with success. “Caught You in A Lie” is an instant hit. As classy as Robert Parker’s original, her cover reggae single is being released in Jamaica.’

‘Like carrying coals to Newcastle, said Delilah.’

‘Not bad for a fifteen year old from Shepherd’s Bush.’

‘Cha! Hush yu mout, chatty chatty children, ‘I said, getting them to pipe down. ‘Yu minds is on vacation and yu mouts is workin’ overtime. Naa mek mi vex. (Don’t make me mad!) No more labba labba. Now hear dis. I run tings here. Gimme de ting what de principal order me. Don’t keep your eaz haad [ears hard]. Mek haste, not ley ley. Memba, don’t dawdle your hours away. Don’t act de giddy goat. ‘Coo yah! No slippin’, no slidin’, no bumpin’, no borin’, no bussin’. No cuss cuss, no back talk. And don’t even tinking of sneaking away, stealing classes or bunking off,’ I said putting my foot down. ‘Be cool, stay at school.’

‘Are you with us, Delbert? I said, noting him staring laxly out the window. ‘What are you doing?’

‘Nothing, Sir,’ he replied continuing to look outside. I didn’t disturb the direction of his gaze. Children from Caribbean families who turned their eyes away when spoken to by an adult, were used to doing this as a sign of deference and respect back in the islands, but was interpreted by the teachers as bad manners, or a sign of guilt for some wrong doing.

‘The problem with doing nothing is that you never know when you’re finished. That reminds me, Delbert, you missed school yesterday.’

‘Not in the slightest, Sir.’

If they seemed lethargic and slack, I stirred them: ‘Listen to Brother Bob. Wake up and live, y’all, Wake up and live! There’s work to be done. So let’s do it – a little by little. Rise from your sleepless slumber!’

With work of scrappy quality, I drew attention to it saying: ‘Ku pon dis. Look at this. No more chaka chaka. Dweet proper like, not like walk bouts. No cribbing from each other. Time you straighten right out. Better think of your future. You’re gonna lively up yourself and don’t say no. You lively up yourself, big daddy says so. Have I got your attention now?’

If they sounded downhearted or unconfident I urged them ‘You can do it if you really want, but you must try, try, try, you’ll succeed at last’. If they waffled the answers they returned, I told them ‘Let your yeahs be yeah. And your no’s be no’. I made it clear through my intonation when drawing upon such patois that it was only for pedagogic effect. It was not to be employed by them any old way in written work.

My first order of business was to make the study of history particularly English history, relevant, dynamic and interesting to these children most of whose ancestors had historically been on the receiving end. Children rightfully chippy about having been born and raised in England, that ‘precious stone… set in the silver sea’, but still seen by a not so good few as outsiders.

This was a task I set about hot to trot, studying English history at the time for my dissertation and preparing for my journeys. I involved my students drawing up a map of England studded with pins, charting locations of interest because of the historical events associated with them. Events that didn’t just happen but typified a process. ‘What I want you to do is forget about memorizing things,’ I told the class. ‘I want you to think history. To consider how events are linked.’

’Our map was to equip us with knowledge of what had gone on where throughout our future travels. Going back through the millennia we considered ancient landscapes, monuments, Roman remains, medieval towns, Georgian squares, architectural wonders, battlefields and so on. I quoted fights historical, from Boudica’s Uprising to Edgehill, in order categorical.

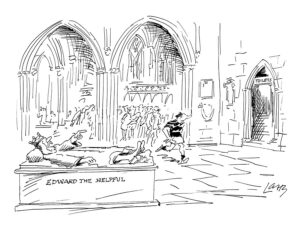

We considered the kings of England,

We observed how other visitors responded to their effigies exhibited.

How some sized themselves up compared to these historical figures,

‘NO! I STILL DON’T SEE ANY RESEMBLANCE’

‘What is Nelson’s Column?’ I asked in a test.

‘Britain’s highest award for valour in war,’ was one answer.

We knew the spots in “Babylondon” where the rebel leader Wat Tyler was killed by the King, where the Princes’ lives were snuffed out and where the King chopped and changed his wives’ heads. All these skanky skeletons in the historical cupboard that make a mockery of the notion that the English – the world’s greatest slavers – had a special civilizing mission in history.

As I assembled them as a group to head off to the Tower, I assured them our revision of transport arrangements and emergency procedures would be brief. ‘As Henry the Eighth said to his wives, I won’t keep you long.’

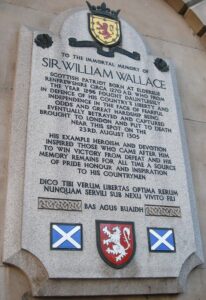

Continuing our time-travel through London’s pernicious past, I took my students to Smithfield an area famous for it’s meat market. ‘This is where some of the nation’s forefathers went on one last ominous outing. It’s an area which has borne witness to many executions of heretics, religious reformers, dissenters and political rebels over the centuries, as well as Scottish knight Sir William Wallace. We gathered outside England’s oldest hospital, St. Bartholomew’s to read the plaque on the wall honouring the warrior leader who would be featured in ‘Braveheart’.

Wat Tyler, the rebel leader leader of the Peasants’ Revolt was also killed here. Those sentenced were put to death in public.’

‘Why not bring the family for a fun day out?’ said one of the girls.

‘Those who came here were already dead meat,’ said one boy. ‘How were they executed, Sir?’

‘Some like Wallace were were hanged, drawn and quartered. Some were hanged drawn and gibbeted- their dead bodies suspended in an iron cage. Some were placed in boiling oil.’

‘Heretics were were burned at the stake,’ said one boy, ‘ just for disagreeing with the religious ideas of those in power.’

‘Who told you that?’ asked one of the girls.

‘My father. It came to his attention in a shop window display.’

‘When did the English stop this barbaric practice?

‘Burning at the stake for crimes other than heresy continued into the 18th century although it was used to dispatch a number of rebellious African slaves in America.’

‘I suppose the slaves were lectured about the superiority of English civilization: ‘Unlike you savages we do not partake in cannibalism or human sacrifice. Now eat your body and blood of Christ or we’ll burn you at the stake!’

We went to Westminster Abbey to inspect the resting place of Wilberforce who tirelessly led the campaign against slavery in Britain. Our textbook gave the impression the British only took part in the transatlantic slave trade so they later could abolish it.

We visited the Chartist offices where workers began campaigning for their right to organize, and the archaeological sites at St. Albans and Maiden Castle where Sir Mortimer Wheeler had carried out landmark excavations.

We learned that for as long as historical records have been kept, Britain has had a homelessness problem.

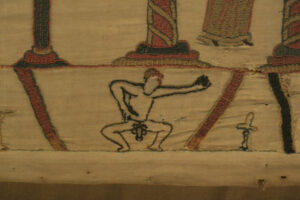

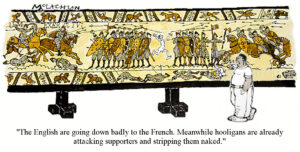

For a project our history class recreated a section of The Bayeux Tapestry as a painting.

The children were amused by the plethora of ‘plonkers’ in this historical artifact.

They cheekily inserted one of their own.

The class carried out this recreation at a time when football hooliganism was at epidemic levels, with beered up bovver boys in their overcoats terrorising the terraces, creating clashing stampedes of young working class frustration. There was a rash of incidents in which Fans of the various clubs were assaulted and had their clothes ripped off by skinheads in red braces.

When the painting was finished one of the boys stood in front of it and proudly gave a running commentary of The Battle of Hastings.

Bete Noire.

It was around then that of the owner of my rented flat in Notting Hill Gate was digging into it’s membership . This landlord was so rude, in my affairs he’d intrude.

There was no problem to begin with. I had been introduced to the flat by Carol Henderson who had settled in after her overland trek. She and her friend were very happy going and sociable, prototypes of those who would appear in ‘Bridget Jones’ Diary’, successors of those in Jane Austen’s novels. They attached great importance to the flat’s strategic social value.

On Carol’s departure, I introduced a black ‘Rhodesian’ teaching colleague from North Paddington Lower Secondary School, Enos Malandu to the lodgings when there was a vacancy. The flat was done up in the same taste as most furnished flats with large brown furniture that cost nothing because nobody else wanted it. After Enos was done unpacking, I heard a howl of laughter coming from the bathroom followed by snatches from ‘South Pacific.’

‘I’m gonna wash that man right outa my hair,

I’m gonna wash that man right outa my hair,

I’m gonna wash that man right outa my hair,

And send him on his way.

If the man don’t understand you,

If you fly on separate beams,

Waste no time, make a change,

Ride that man right off your range.

Rub him out of the roll call,

And drum him out of your dreams.

Don’t try to patch it up.

Tear it up, tear it up!

Wash him out, dry him out.

Push him out, fly him out.

Cancel him and let him go!

Yeah, brother!

Emerging from the bathroom, I asked him ‘Who dat man’?

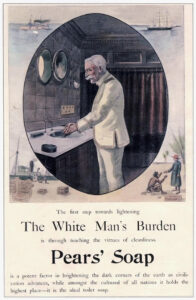

‘Dat man is de Man, de Boss Man, de Bwana, de massa, de ruler of de land. De Downpressor Man. De Coloniser. And I won’t have a bar of him.’ Holding the transparent bar of Pears soap up to the light, he said ‘If this is yo mission to civilize me, yo first step to “lightening yo ‘White Man’s Burden”, I can see right through it’. Pears had advertised their soap thus, as ‘a potent factor in brightening the dark corners of the earth’ and implicitly skin tone.

‘It sounds as though the missionaries beat me to it Enos,’ I replied, holding my sides, addressing him by his biblical name. Which means simply ‘man’.

Leading the fight for national liberation of Zimbabwe from white rule was what made Enos tick.

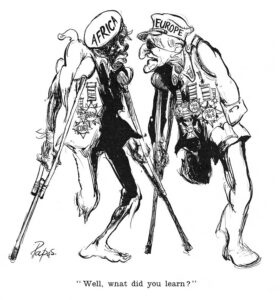

‘The transfer of power took place relatively smoothly in West Africa. Although there have been coups there like in other former colonies,

Ghana continues to provide Britain with cheap food and resources and a safe outlet for investment. Why the bloody holdup in Rhodesia?’ I asked him.

‘Rhodesia has such a substantial white settler population with ownership of most of the land.’

‘They and the Ulster Unionists share the same conflicted cultural overlap, don’t they? They both see themselves as more British than the British.’

‘The Rhodesians define themselves as ‘African of British stock’. “The Surrey with the lunatic fringe on top” is how the joke about white Rhodesia runs. This last vestige of empire resembles the Surrey commuter belt in its parochiality, its golf-club outlook on the world, its unquestioning certainty in its own values.’

‘A corner of a foreign field that is forever England.’

‘With a continual round of gaming, hunting, cricket tournaments, croquet, social visits, picnics and dinner parties, afternoons stretched into weeks. Expats awaiting keenly their Colman’s mustard, The Times and its crossword. Aging, second-rate colonial administrators sipping cocktails in the Cricket Club. Women wearing floral dresses, baking cakes, talking about sewing, petticoats in pink, baby blue, nursemaids, amateur dramatics and wrapping their lips around aperitifs on shady verandahs. Rather than mixing socially with us blacks this clinging to old ways has confined these whites into a narrow life that many of them find boring. This has never changed since they took over.’

‘This is what amazed Tony Benn during the War. He found 60,000 white people with their feet on the necks of the natives . He says they were living off the land that had been stolen by Rhodes from the Matabele and the Mashona.’

‘All corners of Africa have seen the Western countries steal their land and resources. All over Africa today Western companies live off African lands and what’s under them. The only reason they’ve ever been interested in Africa is it’s resources. Minerals, ivory, gold, oil, gas, uranium, slaves. They pretend to the world they want to help but they only want to help themselves. Africa is full of wealth but it’s people see little of it.’

‘Are the Americans helping in any way to facilitate the transfer of power?’

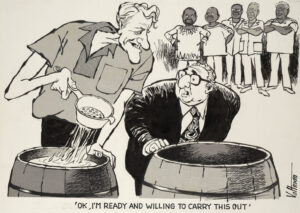

‘Nixon doesn’t show much interest in us ‘niggers’ as he reportedly refers to us. He has been reported to be talking about sending Kissinger to speed up the transfer. But whenever he comes he will find Smith as tricky as ever. For Smith the process of transferring power from white minority rule to black majority rule can be likened to transferring water from one container to another with a sieve. You’ll find lots of holes in it and the net result is no change.

What’s going to happen to the British landowners when they lose control?’

‘Many of these plantationists are just passing. They’ll creep back to Crawley at the first whiff of gunpowder. Tony Benn knows his history. I didn’t know he was there. What was he doing?

‘He was undergoing RAF flying training at Bulawayo.’

‘As did Ian Smith, the prime minister who still wears his old Spitfire pilot’s tie.

You couldn’t find two men more different.’

‘Tony became friendly with an old Matabele warrior who had fought against Cecil Rhodes. It was here Tony’s interest in the anti-colonial movements was ignited. Ever curious about his surroundings, he went to the local hospital for Africans, and found the conditions appalling.

After the war, Tony became involved in the decolonisation struggle of a neighbouring area. He lead the charge to reinstate Khama who had been banished by the British as king of the Bechuanas. He was very close to the Khama family resulting in the them naming one of their sons, Anthony, after him. This didn’t endear him to white conservatives. They had it in for him, seeing him as a traitor to his race and class.’

‘This would have been nothing new to him. He was born with a silver knife in the back.’

‘How do the Rhodesian whites justify hogging so much land?’

‘They believe they have created ‘God’s Own Country’. They say it belongs to those who can work it best. They even believe they discovered it.

‘They say they found an uninhabited wilderness .’

‘Finders keepers, losers weepers. Isn’t that how it goes?’

They believe their race is their destiny. Scratch a white Rhodesian to find a racist. Talking about us they say, ‘ ‘These backward savages didn’t even have the wheel. We raised them up and taught them farming. What have they put into their land? Theirs is dry and barren, ours is green and fecund. Look what we’ve done with it. They are not as deserving as we are.’

‘It sounds like the justification for the Palestine Solution.’

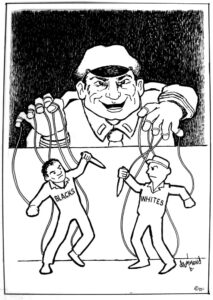

‘It’s still the same old story. The fight from above for glory. Divide and conquer.’

‘What we need, Enos, I said is neither white power nor black power.’

‘What we want is workers power.

So how have the whites been able to get this huge territory to become a dependency, Enos?’

‘To exact tribute, they’ve grafted together territories whose link was more often than not geographical proximity, bringing together peoples who traditionally dislike and distrust of each other – no more compatible than the European tribes who’ve been fighting each other for centuries.

They flaunt their entrenched privileges displaying what they say we can have when we’re like them, when we, the subject people, stop wailing and are ready to take our place in the world one day. But not yet, never today.’

‘These pharisees are very paternalistic. Of course, they are preserving “justice, civilisation and Christianity.”

‘They refer without a suspicion of self-consciousness to us as ‘Our black people’. Their saloon bar prime minister refers to his white-run Rhodesia as home of “the happiest black faces you ever saw’. Bearing watermelon smiles undoubtedly. Yet the breakaways wave their hands in the air screaming ‘Terrorists’ squealing bloody murder over every little concession they have to make to us.’

‘These stalling tactics sounds analogous to what happened in the so-called American Revolution.’

‘UDI, Unilateral Declaration of Independence is an attempt to forestall decolonization just as settler rebellion against the Crown in America. was an attempt to forestall the abolition of slavery. And we know what happened there.’

‘That attempt succeeded until the experiment crashed and burned in 1861. Slavery had to be better regulated.’

‘Our ‘settlers’ see British attempts to enforce these concessions as those of Perfidious Albion.

You can best compare their intransigence to that of the loyalist diehards in Ireland, the first of the imperial territories, and the first to begin breaking away – likewise in a bloody fashion.’

‘And it’s still going on there, Enos. Where do you see things going now back home?’ I asked him.

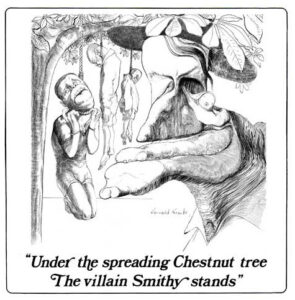

‘We have to bring ‘Good Old Smithy’ and this phoney apartheid breakaway republic to heel, no question.

We have to replace it with one that reflects the interests of workers and peasants – the black majority. Smith has struck a deal with Foreign Secretary Douglas-Home that would legalise the pariah state in return for a new constitution pushing black rule into the remotest of futures. He hasn’t changed this view since he was Prime Minister. It didn’t work then and it won’t work now.

It’s all riding on being ratified by the Commonwealth. Every African state and people insist “No Independence Before Majority Rule”. The British imperialist right obstinately refuse to swallow this historical imperative.

‘Prime Minister Heath says there’s no room for racists in the Conservative Party.’

I can believe that. It’s choc-a-bloc as it is. We’re not going to passively accept their dominion any more. We have to keep their janus-faced government accountable to the values they preach’.

‘This is what the former colonial members are hammering Britain about’, I said. I reminded Enos about De Lisle’s panglossian speech, followed soon by the expulsion of South Africa. ‘How long can the mother country openly flout the wishes of the majority?

‘I don’t give it much time at all. If they can’t get their cosseted bastard offspring to bite the bullet, we’ll ram it down their throats ourselves.

This is inevitable. The land of hope and glory can’t prop up this band of rope and gory. It doesn’t have the resources. They’ll have to pack up and pack it in. We’re stronger, more determined than ever and we’ve got the numbers. Those winds of change have to keep blowing ‘til we blow their house down’.

‘Some would advise you don’t act too precipitately’, I said.

‘I know, don’t fire ‘til you see the eyes of the whites. If we’re going to prevail in our fight for freedom, we need even better organization, training and above all, unity. We can affect things and be actors in history.’

‘How do the diehards justify their injustices, Enos?’ I asked.

‘They get away with it today claiming they are striking a blow for civilisation against ‘Communists’ in Africa. To rationalise enslaving our people in the first place, the colonial rulers elaborated a powerful ideological superstructure with a set of myths, stereotypes and false assumptions to explain everything. In brief, their argument is simply that we are benighted sub-humans: intellectually inferior and childlike.

They claim we are culturally stunted, morally underdeveloped, and animal-like sexually. Of course, they’re not at liberty to say this openly any more in Rhodesia as they do in South Africa-they wouldn’t dare – but they dress it up with fine words. White supremacists use racist and sexist ideas to argue that they alone are civilized and rational, whereas blacks, and other people of color, are barbaric and deserve to be subjugated.

‘They say we have a higher tolerance for pain.’

‘It’s what you would do to justify physically beating another person’.

‘Black men and women are sexually objectified in white society whether here or back home.’

‘They say black people are not as caring about their children, black people are inherently criminal. But what do they know?’

‘These lies and biases provide the white overlords the excuse to get away with their abuses. They are needed to justify the system and are all rooted in slavery.’

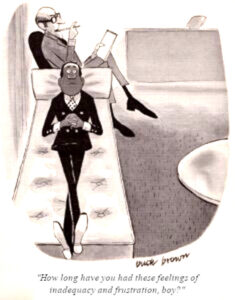

‘What about those based on feelings of white man’s inadequacies? The belief that black men are hung bigger.’

‘My skin is the biggest organ of my body, despite what stereotypers would lead you to believe. The race problem is inextricably connected with sex. The colonists harbour a deep-dyed racist perception of black men as ungovernably licentious. They reckon it’s ‘all that spicy chakalaka’ we eat that heats our blood. They claim we have not only lower IQs but lower impulse control and higher testosterone levels.’

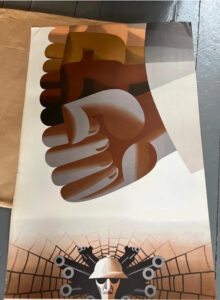

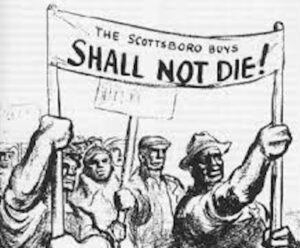

‘That’s how the mobs in the Deep South characterised the innocent Scottsboro Boys, didn’t they?’

‘The Boys – and that’s all they were, their lives hopelessly, eternally interrupted, sent cascading down roads of terror and imprisonment – were nearly executed.’

‘But for a global protest they would have been.’

‘Like most males lynched earlier they were alleged to be rapists. The black man has been portrayed as harbouring an almost insatiable sexual desire for white women. His driving ambition was to rape one.’

‘That prejudice goes way back I believe.’

‘Ever since the English colonists accepted the Elizabethan image of “the lusty Moor”, some white folk out there feel outrage when us men go out with white women seen as being ‘pure as the driven snow’. They see it as a sacrilege.

I can see in their bulging eyes and dirty looks how ill at ease they are when I – a grown man – am with a white lady. Why should anyone of adult age have to consider other people’s feelings when it comes to love between two people?

They’ve never seen see us as humans. As individuals they wouldn’t know any of us from a bar of soap, except when it comes to our labour output. When they came, they said, “No, no, they’re really not men and women, just chain ’em up, tie ’em up, chain ’em up, tie ’em up, chain ’em up, tie ’em up, work, work, work’. They see us as loinclothed sexual predators and potential rapists.’

‘Talking about such a crime, thoughts about black perpetrators have brought out the most savage reprisals. During the era of slavery in America black men convicted of raping white women were usually castrated, their necks stretched, or both, while white rapists of black women were let off the hook.’

Enos used to say ‘I’m going to take a shower and shave. Does anyone need to use the bathroom?’ It was like some quiz where he revealed the answer first. It caught on with Les, another flatmate.

‘I’m using tartar control toothpaste,’ said Les. ‘Does anyone know the best way to get rid of those hard, yellowish deposits on your teeth?’

‘The answer lies in our diet,’ explained Enos. ‘Why do people in Africa so often have sparkling white teeth? We grow up eating less sugary, acidic, processed, chemical foods that decay our teeth and lead to buildup of plaque and tartar.’

‘You the man, Enos. I’ve got so much tartar,’ said Les, ‘I don’t have to dip my fish sticks in anything.’

‘These days, to look fashionably good you need tanned skin and white teeth,’ I said.

‘That’s a shame,’ said Les, ‘because I’ve got white skin and tanned teeth. I was thinking of having my teeth whitened, but then I said ‘forget that, I’ll just get a tan instead.’’

‘One way of explaining the whiteness of our teeth’, said Enos, ‘is that this depends on the context. They appear shining white because of the contrast with our dark skin. If you think of two squares, both of the same shade, the one surrounded by a darker tone than the other appears lighter.’

‘This must mean,’ I said, ‘that white supremacists who believe their skin is the reason for their superiority should mix more socially with darker skinned people. That way their skin will appear whiter — and their thinking clearer.’

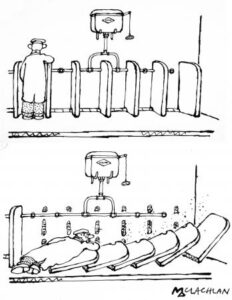

One evening Enos and I went to the theatre together. During the intermission we had occasion to visit the gentlemen’s for the pause that refreshes. There was more drama going on there than back on the stage.

As we approached the urinals a voice called out from one the stalls, “Excuse me, friends, can you find me any toilet paper out there?”

“No, I’m afraid there doesn’t seem to be any here, either.”

The occupant paused for a moment. ‘Listen, he said, do you happen to have a newspaper or a magazine with you?’

‘Sorry, we don’t.”

The occupant paused again, and then said, ‘How about two fivers for a ten?’

This old geezer who was standing by the condom vending dispenser wasn’t much help either. He was banging the dispenser and going, ‘Hey, that’s what automation does to food. This gum tastes like rubber and has no flavour.’

To set him straight, Enos dispensed him the following advice:

‘Don’t be silly, it’s to protect your willy,

On any conceivable occasion with your filly,

It will be sweeter if you wrap your peter,

Cover your skin, it will be much neater,

If you slip between her thighs, to condomize is the rule.’

So, don’t be a fool, it’s to vulcanize your tool.’

When the geezer went to the porcelain to point percy, Enos warned him, ‘I wouldn’t lean too much on that modesty board if I were you, old son. You don’t want to end up in the drink.’

The fixtures in these old theatres were old and budging the dividing panels could lead to a cascade effect.

It was my turn to dispense my own cloakroom sally: ‘If you’re a Russian when you head to the bathroom, Enos, and you’re British when you leave, what are you in the bathroom?’

‘You’ve got me there.’

‘It’s simple. European.’

Staring down at the porcelain, Enos said ‘Someone I could never be accepted as equal to back in Salisbury. Can you imagine how such a simple thing as going to the loo can be so complicated under apartheid.’

He told me about an incident in Salisbury – now Harare – nicknamed “The Battle of the Toilets”. ‘The multi-racial Reps Theatre’s plan for new premises ran into a spot of bother. The new theatre only had toilets for men and women, and there were immediate objections from the Salisbury Public Works Committee. To them, the idea of a black man and a white man using the same urinal was unthinkable. They pointed to Section 142 of the Building By-Laws to justify their objection, warning that, unless separate conveniences were provided, then the theatre would not receive a Public Building Certificate and the new one would not open. These demands were prohibitively costly. Hence followed a lengthy legal challenge stressing doubts to the law’s validity, eventually overturning it.’

At the conclusion of the show the drum roll ushered in ‘God save the Queen’. Theatre and concert goers were still expected to stand. If we had been in a cinema, we could have joined the headlong audience rush out while the end credits played to avoid this formality. Now we commoners had no chance of escape. Enos and I stood up but remained silent during the anthem.

He asked me later, ’Do you ever feel pressure to sing along?’

‘How can I exhort an entity that doesn’t exist to save one that shouldn’t. Why should I belt out the praises of a hereditary monarch, an absurd anachronism whose claim to rule because of some accident of birth is an insult to reason and democracy. Mind you. I’d like to have a penny for every time I’ve heard it played.’

‘I’m happy to hear it incorporated by Beethoven in his “Battle Symphony”. But what uninspiring lyrics! It doesn’t talk about the country’s people, their hopes and aspirations, as the best anthems do. It doesn’t shout about a major historic triumph either, a moment the country stood firm, then use it as a way to inspire. It doesn’t even say the hills of Britain look nice, which is surely the bare minimum requirement. What about you, Enos?’

He explained: “It’s my personal choice not to sing it. Isn’t that what freedom’s about? If I were to sing the British national anthem, that would be disrespectful to the place I come from, to Zimbabwe, to my family, because the anthem represents something today that causes a lot of conflict and pain there. A lot of people are still hurting there so I can’t pretend that this isn’t happening. I will stand in silence while the anthem is played. I will respectfully allow others to sing it. I won’t interfere, but I can’t take part in that. The people that love the anthem are British, that’s their culture. They go all gooey when a rich family wave from a balcony. I totally respect that, that’s great. I wouldn’t ask them to sing ‘The International’”.

‘What about the argument that family are good for tourism?’

‘Does that mean no tourists ever go to republics like France or the US? Or if they do, do they climb to the top of the Eiffel Tower, look down on Paris, and say: ‘Well, it’s a lovely view, but the lack of a monarch spoils it somehow. My attitude is live and let live, and I don’t think we should have ideas forced on us just as I don’t want to force my ideas on anyone else…I have to stand by my principles.’

‘What’s your response to those who say you should be more grateful for being permitted such easy access to the UK?’

“Britain has some of the most stressful entry requirements I’ve ever come across in my life. You can be asked so many questions. The immigration officials at Heathrow look at me as if to say: ‘So you’re a teacher, you don’t look so educated.’

‘So, at one point I stopped and I said: ‘Look, Sir, I’ve given you the paperwork, I’ve told you why I’m here, why don’t you believe me?’ The official said: “Well, the truth is, we can’t just believe everybody that comes into the UK, we can’t just believe that you’re going to do what you say you’re here to do. You might do something totally different”’.

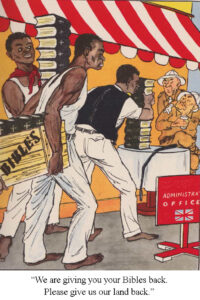

“I thought: ‘Fair enough, that makes sense.’ I just wish, as Africans, we’d thought of that when you British arrived. That would have served us well.”

Our Jewish landlord certainly didn’t serve us well. We couldn’t get the Anti Discrimination Board to overturn his decision to kick us out. We realized this was a matter you couldn’t easily prove in practice. It was our word against his.

Using his own qualifiers, Enos concluded sardonically quoting Enoch Powell, ‘The indigenous Englishman’-[whether jew or gentile]- ‘should not be subjected to an inquisition as to his reasons and motives for behaving in one lawful manner rather than another.’

Carnival.

The Notting Hill Carnival, which has become the biggest shindig in Europe proved to be a smashing opportunity for my students to display their interest in the past. I saw it as an opportunity to instil in them pride and dignity in their heritage.

Begun as an expression of freedom following the race attacks in 1958, the event built on the carnivalesque tradition in the West Indies, particularly Trinidad, and became finely adapted and returned to the migrant experience in Britain. With its emphasis on masquerading, it takes all manner of subjects of interest as its raw material for costumes.

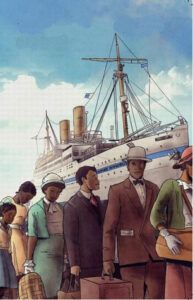

Under my direction my students created a cavalcade of characters representing the theme of movement of people to Britain throughout the ages.

I put the following question to my colleague, Keith Morton, ‘You take the response to the problematic state of race relations at this time, you showcase elements of a Caribbean carnival in a cabaret style, put it all together and what have you got?’

‘I can’t say exactly.’

‘I haven’t the slightest idea either but it’s an interesting question.’

Preparing for this two tone whoop-de-do was a long-term thing. We researched books in class to make sure the costumes were authentic.

In the case of the ‘Windrush’ passengers, all this group had to do was to get their parents to drag some of their old clobber out of mothballs. For the others this required procuring bright coloured off cuts of cloths, some liaison with drama departments and trips to museums.

The girls had to learn how to apply makeup properly. One drama teacher told one of my girls she was drawing her eyebrows too high. She looked surprised.

Designing and completing what costumes we couldn’t borrow was carried out by the student’s families in their homes. As the coloured girls went do di-doo, do di-doo, the sewing machines were kept purring and hands all go stitching and sewing well into the night in the lead up to the big day.

People had been praying for weeks for a sunny day – not that it made a difference to them attending, but it could deter them from wearing their skimpiest and expensive outfits bought specially for the occasion. It didn’t deter them from trying them on there and then.

“Do I look fat?” asked one lady bursting at the seams.

“You’re not fat,” I assured her, “you’re just… easier to see.”

Some of the ladies costumes were so tight, I had difficulty breathing. They looked as though they’d been poured into them and forgot to say ‘when’.

I warned one of them, ‘Take it easy, my blood has a low boiling point!’

Flouncing around the room in their getups, they set the tone for the big day. They let it all hang down, causing talk and a touch of suspicion in this exhibition.

‘Wait til yah see me in me heels, alter back and ting …’ one of the ladies said as she chilled out while changing. She was referring to the halter back top popular then. ‘Mi a go uptown top ranking. Sey mi gi’ya ‘eart attack.’

I almost had one there and then.

They got it on, partying the way they knew how, like there was no tomorrow. Women danced and sung while they steamed goat curry in a pot. Young lovers traded flirtatious insults, then kisses. Families gathered around the dining room table and joked with one another in patois.

On the day, every float, every stage, every performer and every person told a story – and that story is how music, dance and community can bring people together.

Along the route crowds jostled for a better view of the approaching paraders in all their finery. Performers in elaborate headdresses danced at the front of the masquerade procession.

flatbed lorries, dressed up with balloons made their way along at five or ten miles an hour with kids running alongside and people pulling them on.

Leading our contingent, to the rhythm of a steel drum band,

were representatives of Romans, Danes and Normans from all walks of life, all bringing their skills and services with them to this occupied island, all flanked by soldiers. Bringing up the rear were passengers from the ship, the Windrush, symbolizing the arrival of the first postwar generation of black Britons.

Lugging their suitcases along the Portobello Road, this advance party recalled those pioneering new arrivals. They expressed their reactions to the sights and sounds of what they had been led to believe was their mother country. At pedestrians hurrying quietly along, at crawling vehicles, no horns blaring angrily at the goofs of others. No one shouting at friends on the street.

Without the need for military accompaniment, some wearing medals indicating military service for King and Empire, the point being made was that these were just the latest of a long line of boat people coming to these shores, simple workers whose forebears had shed sweat and blood for Britain, and who were only looking for a better life. The group was received with cheers of approval as it wended its way along the pageant’s course.

My students had taken steps to strengthen their community’s roots in the British cultural landscape, not just by reminding people of distant exotic islands but by asserting their dibs on the only home they knew. This was a claim increasingly under threat thanks to the rise of the National Front and the skinhead culture.