Travelling North.

After Zurich I thumbed a lift north with a short middle aged Hamburger, salt and pepper hair combed back, without parting, from his forehead and dark circles around his sleepy,baggy eyes. Gravity now had such a grip on his features that his eyes had nearly lost their battle to stay open. If our faces are the road maps of our lives, his progress had been dizzyingly downhill. His face was saggy, full of the disgust of life and the thickening effect of alcohol. His pallidness, hollow cheeks, angular features and five o’clock shadow that looked creepily like the growth of beard on a corpse, gave him a diabolonian air.

I caught him when he stopped at the border and he didn’t have time to object when I piled into his auto. He didn’t speak any English though his words, purveyed in a baritone growl, sounded as if they has been passed down to him by generations of schnapps drinkers and chain smokers of cigars. I travelled with him dusk to dawn on the autobahn while he seemed to satisfy himself by babbling on. I showed my gratitude gibbering on convincingly in a thick accent mimicking the sounds and cadences if not the sense of German. When watching all those wartime films I had observed how the Germans had formed their lip movements and the intonations. That’s where I picked up words and sounds. In this doubletalk I mastered my use of the word ‘ja’ and ‘achtung’ which is a bit more limiting.

During the trip late at night this driver decided it was time to take a break to get some food.

‘Mahlzeit’, he announced, pointing his fingers towards his mouth.

We exited off the motorway and drove around a small town for ages looking for any diner that might be open.

After seemingly driving around in circles a good while we came upon one of the earliest Turkish doner kebab cafés.

While waiting to eat at this hole in the wall eatery, my driver went to the toilet.

I attempted to communicate with the proprietor as he shaved seasoned lamb from a rotating skewer.

It turned out he could speak sufficient English. He said to me, ‘Do you know a little German?’

‘Only my driver. I’m having great difficulty getting through to him.’

‘Then I will help translate what he says for you.’

On his return my driver asked this gastarbeiter trying his hand at food service ,‘Weissen sie, wie ich zur Autobahn zurückkehren kann?‘

‘Do you know how I can get back to the autobahn?’ the proprietor translated for me.‘

The proprietor thought for a few seconds, then while topping the rice with salad said to my driver, ‘Nein‘.

‘Weissen Sie der nächste Autobahnkreuz? ‘

‘Do you know the nearest autobahn interchange?’

‘Nein.’

‘Weissen sie in welche richtung Hamburg ist ?

‘Do you know what direction Hamburg is in?’

‘Nein.’

After taking the first bite from his plate, then licking the chilli sauce and yoghurt garlic dressing from his lips, my driver said in exasperation , ‘Sie weissen nicht viel, oder, Abdul.‘

‘You don’t know very much, do you, Abdul.’

‘Nein, aber ich bin nicht verloren.‘

‘No, but I’m not lost.’

From Hamburg the last leg of my journey was to wonderful Copenhagen.

The Big Chill

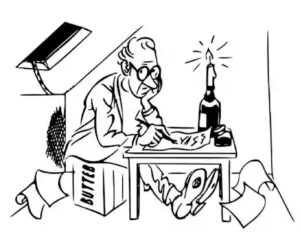

Cool man. I didn’t plan my arrival well, arriving slap in the middle of the northern winter. My garret, just below the roof, was cramped and gloomy ,especially when the power went out.

I took to writing as best I could, comforted by the conviction that noble poverty is to be embraced by the artist. The box I inhabited was so cold I had to put the milk in the fridge to stop it freezing. When I used the phone I could see the breath of the person I was calling coming out of the receiver. I look back on this as my Blue Period. I woke up each morning at the crack of ice, watching the icicles form.

Cold in my extremities, I rubbed and blew on my hands in a losing effort to stay warm. I urged my radiator ‘Turn on the heat, twenty degrees. Get hot for Allan, or Allan will freeze. If you are good, my little radiator. It’s understood, I’ll polish your pipes later.

I had a go at skating on the ice. I realised it to be an experience and range of temperatures your body doesn’t want to go through. Ice has evolved the way it has for a reason and doesn’t want us on it’s back. Normally when you trip, you put your hands out to avoid any damage. On ice at Kongens Nytorv Square I splayed out and slid for another fifty yards surrounded by out of control teenagers with razor blades on their feet.

Nevertheless my chapped skin was warmly welcomed in by the Rasmussens, parents of my friend Jan. He had married my former biology teacher and came to live in Gunnedah via the hippy trail the other way, to set up a car dealership. The Rasmussens made me feel at home. I landed a job storing and packing in the warehouse of large company, Paul Lehmann.

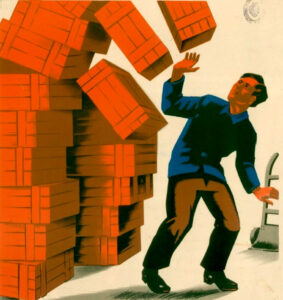

‘As you can see, Allan,’ said the manager, showing me around, ‘we place great emphasis on workplace safety. We comply with environmental, health, and safety regulations. We handle many materials manually. With regard to your personal safety we cannot stress enough the age old “lift with your legs, not your back” advice.

‘That’s all right. I lugged around and lifted many a box in my parents’ business.’

‘So you’ll remember how we ensure boxes are stored in the right position.’

‘We have to make sure any boxes are stored according to the labelled instructions.;

‘They have to be stored vertically according to the “This side up” marking. This placement makes sure the carriers handle the boxes according to the preferred orientation.’

‘And they have to be stored at the right height.’

‘Correct. We have to be very careful not to stack boxes too high. Remember the higher items are stored, the more dangerous they become, so it’s always best to keep stacks short whenever possible.

A lot depends on different variables such as the contents of the box, its weight and size.’

‘I see you have a lot of materials on pallets.’

‘Of course we now depend greatly on placing most goods or materials, either packaged or bulk, onto pallets. The pallet provides a base for the goods and materials. I want you to think of more efficient ways of storage, handling and transport for the combination of goods and the pallet base. We refer to these collectively as the unit load. Its weight should never be exceeded as overloading can cause damage to stock and injury to workers.

’Receiving stock, selecting and preparing goods for dispatch, loading and unloading trucks kept me moving and warm. The warehouse offered me refuge from the elements.

One frosty morning I asked the foreman, ‘May I close this window?’ It’s cold outside.’

He replied, ‘If you close the window, it’ll be warm outside?’

Gender equality being a cornerstone of the Danish welfare state, when it comes to equality parameters, Denmark has been on the forefront for more than hundred years. Paul Lehmann took on Anne who proved adept at loading and unloading materials, ensuring loads were secured and completing tasks quickly and accurately.

Sometimes what made up the loads weren’t quite what management had in mind.

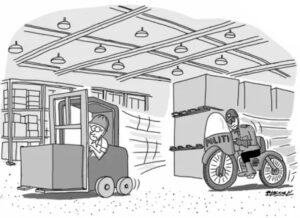

He asked if I too could drive a forklift truck.

‘I’ve no experience but I pick things up quickly.’

‘Just as long as you don’t drive too quickly. The government ensures we comply with speed regulations.’

I once had to lift a crate of forks. It was way too literal for one of the clerical staff. ‘Why do they need a great machine like that just to lift forks?’ he asked. ‘They’re only made of plastic, aren’t they?’

I had to wear a helmet driving the truck but I removed the horns which got in the way.

One Thursday lunch break I drove wildly round the warehouse, brandishing a hammer, lashing and lisping, I’m Thor, I’m Thor, North God of this day, and I’ll thlay any troll who geth in my way.’

One of my workmates Mogens went along with the joke crying, ‘Of courth you’re thor, Thilly. Your chariot’s not thoft enough.’

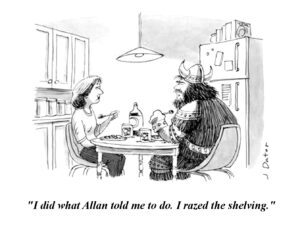

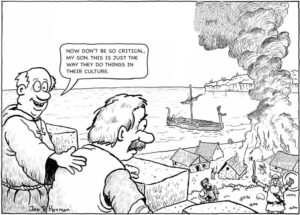

I had to pass on a directive from the foreman to Mogens. He had to ‘raise’ some shelving in the warehouse. With Viking blood coursing through his veins, Mogens not unsurprisingly took on board the homonym of that verb.

‘Your days of pillaging, looting and slaying are well behind you,’ I said to him.

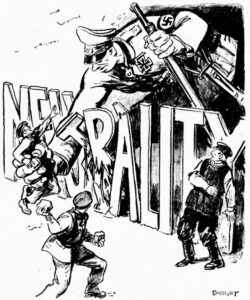

‘The dummkopf Nazis didn’t seem to know that, would you believe. Germany signed a ‘non-aggression’ pact with Denmark in May 1939. How nice was that. Afterwards the Germans could sleep in peace, knowing that they would not be invaded by us.’

Mogens told me what Victor Borge had said about the effect of humour, ‘A laugh is the shortest distance between two people.’

Noticing the magazines on retail display, censorship having been greatly relaxed, I concluded there are other sounds and movements even shorter.

One of my duties was to get drinks from the corner shop for smoko. Here too, times had changed. We drank not mead out of skulls but beer straight from the bottle.

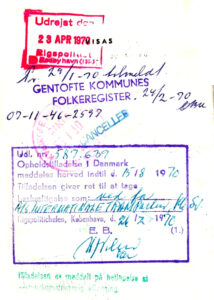

I ended up with the documentation necessary for future citizenship.

At Gentofte Folkesregister, I was officially admitted as a resident, which I took as a great honour. While I was there, a local, Lejf Hansen found his name missing from the list. The civic official apologized profusely saying he simply couldn’t account for the disappearance. I had my own theory. I said ‘I think I know what’s happened. You must have taken Lejf off your census.’

Few had difficulty following me and were happy to be let in on the semantics. They rarely heard their language spoken by foreigners, so it was easier for them to switch to English than it was to try to understand my accent.

Danish is difficult to learn. Only half of the written letters are pronounced in conversation, and a combination of guttural “r’s” and soft “d’s” make developing the proper accent a lifetime achievement.

There is nothing like a Dane. While I was in Nuhavn a Swedish man was arrested for disorderly behaviour. He was so drunk the police thought he was Danish.

There’s been recent speculation that even the Danes don’t understand each other.

Nevertheless I refused English as far as possible and ordered the tongue twisting, mouth watering Rødgrød med Fløde – Danish Red Berry Pudding with Cream- with panache.

I demanded my right to speak the language and learn the culture.

Mogens pointed out the house he told me was lived in by one of Denmark’s leading music composers.

‘Was that Carl Nielsen?’

‘No it was Mendelsen.’

‘Wasn’t he German?’ I asked.

‘Not this one. I’m talking about Hans Christian Mendelsen.’

I do find the Danes a liberal and gentle people, but I realised it was hard for an outsider like me to fit in professionally and economically. After sussing out the prospect of getting professional work, I concluded that this would have been a long way down the track, if at all. I wanted to complete my external course from my university and after casing out the grand State and university libraries, I worked out that I wouldn’t have the necessary books in Copenhagen. Living the proletarian life in this climate was too perishing cold for my liking. It didn’t mix easily with my interest in the current political and romantic movements. I couldn’t do anything about this on a seasonally adjusted basis so, time to split, I resorted to what most expats do – head for London Town.