‘We are no better than anyone else, any of us.’

Pearl Buck.

“Whey Out. What a choice!” I marvelled as David and I scanned the dishes sitting on the hotplates, poised to serve ourselves from the vast selection of foods laid out on the sideboard. This was international students’ night and the main drawcard was the smorgasboard of varied dishes that one could discover. This way of serving worked well as there weren’t enough chairs for everyone. My gastric juices flowing full pelt, I homed in on my favourites, the range of tasty Chinese appetisers.

“Yum,” I said with anticipation.

“Yum Cha” added David, rounding out their name.

“I’ll have a bash at this,” I said heaping some bean curd with cabbage onto my plate.

Once seated I began to manipulate my chopsticks so I could get as much of the dish as possible into my mouth. ‘It’s an interesting thing about the Chinese people how they retain use of the sticks, aren’t they? It’s not like they don’t know about forks. Yet they’re staying with the sticks in food consumption. Why not in food cultivation you might ask?

Well here’s your answer. A Chinese farmer gets up, works in the field with the shovel all day. Think about it. Shovel, spoon. Shovel, spoon. They’re not ploughing their fields with a couple of snooker cues, are they?’

“They’d really rough it breaking up a grassy tuffet. Now Little Miss Muffet, served from the buffet—,” punned David, rhyming “buffet” with “muffet” – as I had done myself on a childhood train trip, not yet ‘au fait’ with the worldly-wise way.

“—Eating her curds and whey,” he went on.

“No whey José”, I struck back, “just the lumpy stuff. Whether its cottage cheese or soyabeans, it’s the curdled solid where the value lies.”

‘Hanging’s too good for a man who makes puns,’ said David. ‘He should be drawn and quoted.’

I then treated David to my variation of the Miss Muffet rhyme:

“Little Miss Pearl, a slip of a girl,

Eating her curds and kraut.

Along came a Boxer who sat down beside her

And frightened her all about”

“My goodness” exclaimed David. “What inspired you to that?”

“My reading of ‘The Good Earth’ whose author ate thus as a child. Who was given the screaming willies by the Boxers. Who witnessed blood curdling events. The author was Sai Zhen Zhou.”

“Sai Zhen Who?’’ queried David, “don’t you mean Pearl Buck?”

“The one and the same. Sai Zhen Zhou is the Chinese persona of Pearl Buck. A highly cultured rare pearl in my literary oyster. She wrote “The Good Earth” while thinking in Chinese, translating it as she went into clear, strong English. Wen Chung must have smiled encouragement upon her. Profusely. Prolific writings I can do no more that sweep through. These I imagine must be up your street what with your interest in cultural interplay. Not to mention your desire to foster greater mutual understanding between Australia and Asia.’

‘By building trust between both peoples. A two way street.’

‘Think about this, Allan. If our friends from the north and their hosts experience cultural shock in the Australian context, spare a thought for fair wee blue-eyed Pearl threading her way through a sea of oriental faces. Great day in the morning, can you imagine the start this girl with her Valkyrean looks and straw-colored hair brought to these when she revealed her fluent Chinese, her first language.”

Ditto the reaction of the Englishman in her novel ‘The Promise’ when he encounters a local girl and his words fail him. “One doesn’t expect a Chinese – to…”

“- be wholly human” she adds, finishing the sentence for him.

‘Hardly a Christian approach,’ said David.

‘Pearl’s father had similar expectations. He was a missionary. An excoriatingly zealous one at that.’

‘One of those blue eyed bible thumpers who couldn’t stand the commercial pace back home, I take it.’

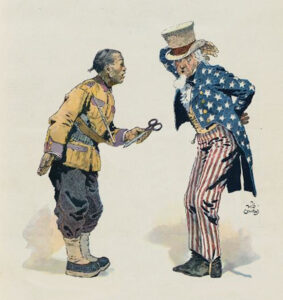

‘He was from a slave owning American family, steeped in the idea that racial hierarchy is natural. In her biography of her parents she speaks of his lack of warmth and ‘holier-than-thou’ attitude towards the Chinese.As a representative of the United States, he expected the men to do away with their traditional queue hairstyles.

Needless to say, this disdain would have rubbed off on them, he being one of the limited Westerners they would ever come into contact with.’

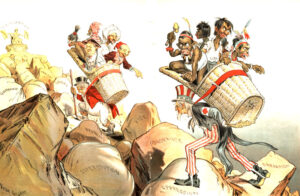

‘As were the venture capitalists making sorties outside their coastal strongholds – “No dogs or Chinese allowed” – to smell out new sources of profit,’ said David. ‘Likewise the occupation armies stationed there to enforce these interests through their gunboat diplomacy. Speaking softly, carrying a big stick. The White man’s burden as interpreted by the President Theodore Roosevelt.

He called the Chinese “an immoral, degraded and worthless race”.

‘Not unlike how some haughty Chinese viewed Caucasians’ I said. ‘As a child Pearl was taunted as a ‘foreign devil’. Robbed of the upper hand of history, resentful nationalists, feeling powerless could only lash out wildly at the white ‘civilisers’. The barbarians at the gate to the centre of the known world’.

‘How did Pearl react to this treatment?’

‘Quite personally. As a child Pearl thought she was Chinese. When she asked her Chinese nanny why her blonde hair was being covered up, the nanny said: ‘It doesn’t look human, this hair.’ Pearl only realised she wasn’t Chinese when she was eight.

I imagined the conversation that took place when her mother broke the news to her.

Mother: ‘It’s your birthday, and it’s time you knew. Sai, you’re not a natural born Chinese.’

Sai: ‘I’m not?’

Mother: ‘You’re not even asian. You’re a Caucasian. But we raised you like you were a Mongoloid.’

Pearl: ‘You mean to say my eyes are going to stay like this? All big and blue. And my hair blonde?’ Pearl cried.

Mother: ‘We can always dye your locks, Pearl. Doctors say one day you could have your eyes surgically narrowed. Just remember I’d love you if your eyes were square shaped and the colour of a panda’s navel.’ Pearl and her mum hugged.

‘What conclusion did Pearl draw from the unfortunate way different cultures came together?’ asked David.

‘Pearl realized the importance of people from different cultures reacting with one another in a constructive way, leaving all enriched, not at the expense of the other. She looked for good in people and found the qualities that she rated highly – kindness, dignity, compassion, courage, wisdom and love in the most lowly. She aimed to reciprocate these through her words and actions. Seeking to prove to her readers that universality of man and woman can exist if people want it, she concluded our common humanity.’

“What did she base her stories on Allan? What is their setting?” He asked, pausing to sip his jasmine tea.

“She relied on her life experiences as the basis for her authentic stories,” I said. “She was a keen eyewitness to the making of the modern Chinese nation. She has taken me beyond those journalistic accounts I am familiar with, primarily concerned with China’s political fate. Having grown up and lived in impoverished rural communities she set her stirring stories against the backdrop of the turmoil and revolution that have rocked this century in China. She populated them with peasants, bandits, warlords, slaves, concubines, women beset by bound feet, floods, famine, pestilence, occupiers, and looting. People dropping like flies. Biblical in proportions”

“Meaty stuff for such a babe in the woods,” commented David “What were some of the events she and her characters had to contend with?”

“The saddest thing she came across during her childhood was the bodies of babies left abandoned on hillsides. She took it upon herself to bury them and to carry a big stick herself, one especially sharpened. She wielded it to drive off the dogs feeding off the young corpses. The point she made was that the Chinese were being overwhelmed by the endless calamitous events visited upon them. Her famous character O-Lan resorted to strangling her fourth child. Otherwise she would have died from starvation. It wasn’t them that were cruel or degraded but the times they were living in. They needed food and family planning.”

‘How did she fare during the momentous events that shook China’s industrial and political catch up?’

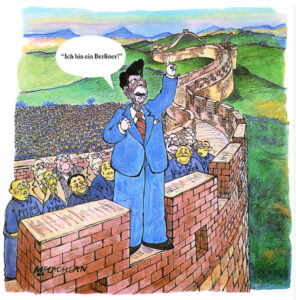

“She got way-laid more than once on China’s turbulent road to modernity and freedom from foreign interference. Caught up in the internal divisions and periodic out breaks of anti-foreigner violence in 1900 she had to be evacuated to Shanghai during the Boxer rebellion.”

‘Better there than Peking’, commented David. The cinematic scenes of the 55 days spent there by Westerners under siege were still fresh in our minds.’

‘Her father never went out without a stick to beat the dogs loosed on him by the Chinese wherever he went.’

“I must point out that sooling Westerners into leaving was akin to the anti- Chinese violence on the Australian gold fields. The Chinese were feared to be getting more than their fair share. There were rowdy demonstrations against Chinese labour feared to be driving living standards down. But don’t let me digress, Allan. Please carry on,” he said.

“She and her family had to flee again during the blood-soaked civil wars of the twenties and thirties. She experienced the violence known as the Nanking incident. Several westerners were murdered in a bamboozling battle involving elements of Chiang Kai Shek’s nationalist troops, Communist forces and associated warlords.

Pearl’s family escaped by a hair’s breadth, spending a terrified day in hiding after which they were rescued by an American gun boat.

“That rings a bell,” said David. “If she were there today she’d once more be fearful for her safety. From the frenzied chaos of the great cultural revolution going on right now.’

‘From what I’ve heard of it I’m better off being here tonight.’ I said, ‘advancing softly, gradually, carefully, considerately, respectfully, politely, plainly and modestly. At a dinner party, not Mao’s revolution’, I said rejigging the elements of Mao’s dictum .

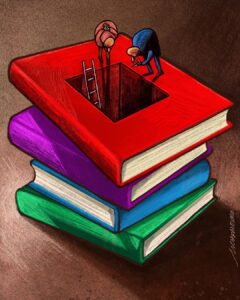

“Do you see a common theme running through Pearl’s books when you drill down into them??” asked David.

“I’d say they deal with personal suffering in a world racked by social upheaval and how one copes with it.”

“A universal theme if there ever is one,” David commented pithily. “Do you enjoy reading this literary leading light?” he asked.

“On the whole, very much so,” I replied. “ I always have one of her stories on my bedstand. Pearl really takes us somewhere. You can truly feel what it is like to be a Chinese farmer without a yuan to his name. Her books pull you their very world so that all else disappears. Indeed, I have written to her telling her to that effect. I told her what I find particularly appealing about her works is the balance she achieves writing about heavy violent behaviour by humans on one hand – our unfortunate reality – and their light sensitive touch on the other.”

“This concept of balance of opposites is central to Chinese philosophy,” said David, ‘although I can’t remember what it’s called in Chinese. Can you?’

‘No. It wasn’t on the menu.’

‘It’s on the tip of my tongue. Yin and yang. That’s it.’

‘So I gather,” I replied, adding some cashews and sliced water chestnuts to my plate to balance textually the softness of the bean curd, and drizzling it with piquant soy sauce to balance flavour-wise its blandness.

“The idea is that everything is made up of opposites which are inextricably intertwined.’

“Try, try, try to separate them,

Its an illusion”, I sang sotto voce, sampling “Love and Marriage”, the hit from Tin Pan Alley.

“This I tell you brother,

“You can’t have one without the other” came back David, getting into the swing of things, proud to be as quick to quote Ol’ Blue Eyes as he did Chaucer.

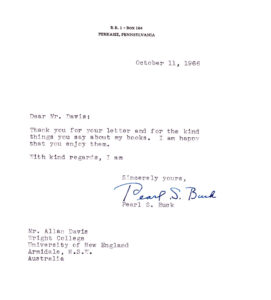

“You say you’ve conveyed your feelings to Pearl?” David asked.

“I have, David, and await her reply with baited breath. I’ve put a lot of thought into my comments and would love her to acknowledge this.”

The Response.

It would take some time before I could breathe more easily and relay Pearl’s warm response.

‘What’s the latest bulletin?’ asked David.

“Pearl thanked me for the kind things I said about her books and was happy that I enjoyed them.

“I think I’m entitled just this once to be unashamedly corny. I can lay claim to having bucked Pearl Buck up.”

“Half your luck. What did you say to her, Allan?”

I thanked her for the penetrating perception she provided of China and her particular sensitivity to many aspects of life there which Chinese writers have taken for granted. I thanked her for changing the distorted image of it in the public mind – one of dark mystery and unspeakable vice – and for cutting across stereotypes at a time when these were – and still are – so entrenched.

I pointed out to her that there was an influential current of thought in the student body here at U.N.E. which sees even educated Chinese – including our students from the Chinese diaspora –as unbelievably strange, sneaky, crafty and at best inscrutable like Sax Rohmer’s Fu Manchu. I assure my peers there is no mystery in the Chinese way of thinking if you take the time to talk to them.

I told Pearl how moved I was by her intricate and truly epic portrayal of peasant life in a land still out of bounds to most of us. That she had provided me with a greater understanding of it’s poverty, famine, and imperialised past.

Moved by those of her books which contained narrative and descriptive passages of considerable drama. Composed of innumerable intimate commonplace details, they make up a storehouse of knowledge about Chinese traditions and customs. I cited her scrutinizing description of the groom, Wang Lung’s rigmarole on the morning of his wedding – plaiting a tassled black cord into his pigtail, taking care not to waste any precious dried grass, leaves, and stalks as he kindles his fire.

I drew her attention to how she had covered much of the same ground with her near-photographic depictive precision as had Cecil Beaton with his lens.

Their graphic representations of Chinese life complement each other so well.

Pearl’s minute observations breathed life and movement into the characters and scenes Cecil captured on his camera during the Second World War. She had an abundant ability to enter imaginatively into other people’s lives. The daily struggles, the ebbs and flows, the relationships, human needs and human nature all summed up in her novels.

Aware of David’s interest in the visual arts, I later showed him my collection of superb photographs of China, in which Cecil produced a vivid picture of Nationalist China in its last years. Poring over this invaluable record David shared my sense of awe, that which I had expressed to Cecil as well as to Pearl. His evocative portraits of the Chinese heartland captured moments of a period long gone.

‘How about that?’ David said admiringly. ‘This great artist has chronicled terror and beauty equally well. He’s left us a view of the past that seems so immediate – yet so lost.’

‘The past is another country. They do things differently there.’

‘Beaton had no choice. Because of the War he had to forgo access to the best German optical technology . When asked how he felt about this he answered in Chinese English, ‘Lao Zi. Me no Leica’ .

The scenes Cecil depicted reveal the essence of China at work.

He showed us the drying by sunlight of noodles, an essential ingredient and staple in Chinese cuisine.

He showed us bamboo poles being soaked to prepare them for construction.

He photographed four coolies carrying their loads on a single pole up the wharfside steps at Chungking (Chongqing).

He captured the beauty and grace of the landscapes and buildings ,

This police headquarters features a round doorway often referred to as a moongate because of its shape.

It represents the full moon, or happiness, a symbol frequently used by the Chinese to protect them and where they frequented from evil spirits.

The HQ would have needed more protection than most.

He provided us with photos of the appalling bare-foot poverty and the hardship.

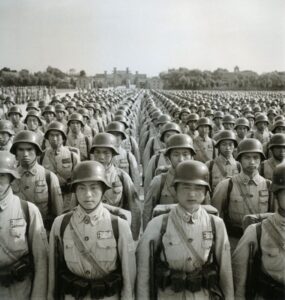

He showed us the doughty fighters against the Japanese invaders.

My eye had instantly fallen on the picture of the Chinese soldiers who had to defend themselves against mustard gas and blister agents.

It would fall to these cadets to defend the motherland from such terror.

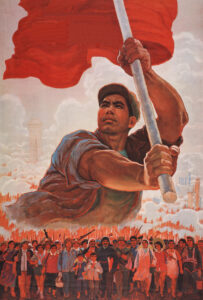

In the propaganda campaign against the invasion, the subject matter of Cecil and Pearl strategically overlapped.

I complimented her on the vast array of unforgettable characters she had introduced me to: simple, kind, even noble characters she had represented with empathy, compassion, honesty and forthrightness. In particular I shared the feelings of the strong women in her pages, often reflecting her own character – stoic, energetic, independent-minded sisters I was stunned by the scene in “The Good Earth” in which a peasant gives birth over a bucket… then goes straight back to hoeing the fields. I was moved to pity for her and horror at her plight. At that of another in “Mother” who endures untold tragedies – being deserted, rearing a blind child, becoming sterile, but never accepting defeat.

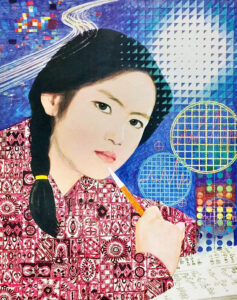

Of real flesh and blood, she expresses clamant sexual needs and longings. I was eager to learn more about the connubially unhappy Chinese woman who falls in love with a western priest. Relationships between men and women across ethnic and class lines particularly fascinated Pearl. I felt the ignominy of corpulent unlovely O-Lan, devoted wife to Wang Lung, traded-in and upgraded for a newer sleeker model after she had served her purpose. Such lack of appreciation. I was full of admiration for the heroic women in her stories of war and resistance.

I was amazed by the elderly Mrs Wang in “The Old Demon” who saved her village by opening a dyke gate and drowning the entire advancing Japanese along with herself. Ditto the hero in “Dragon Seed” who manages to poison a gathering of Japanese officers. And the female head of a band of guerrillas in “Golden Flower” who harasses the Japanese in a long series of audacious raids. As did Vietnamese women warriors to the south, as they do today against Saigon’s American backed forces. Women valued by their male comrades for their military skills rather than for their appearance.

“Do her characters ring true for you? Are they realistic or are they cardboard cut-outs?” David asked. ‘Do they really speak to you? Can you relate to them?”

“They are real for sure. Women came to the fore in both Nationalist and Communist camps.

What I find appealing about Pearl’s is that I can identify with them so closely. They resonate within me as I discovered commonalities I scarce thought possible. They are not the caricatures we’ve received via Hollywood of depraved, imbecilic opium smokers with long fingernails and chopstick-size mustaches. You forget quickly that they’re foreign. Their joys, sorrows, problems and disillusionments transcend cultural barriers. You live their lives as they see them and feel them. They are specifically Chinese living at a certain time and in a certain place. But the more you get to know them, the more you recognize them as others you know right here. They are so alive that I see them as people around me. Her farmers are representative of sons and daughters of the soil everywhere – their thought processes, their habits, their industriousness, their frugality, their god-fearing ways, and their attachment to a particular patch is no different to those of the farmers you and I know so well. Like Dad and Dave, Wang Lung, the farmer is out of his element in the fast-paced, big bad city. In reduced circumstances all we humans react to life events in much the same way.”

‘So you enjoy reading her writings on China?’

‘So much so that after reading one I want to go back and read it again.’

“Did you single out any particular book as having made the greatest impression on you?”

“Indubitably her masterpiece “The Good Earth”. I read it in one sitting.’

Putting me to the test, he asked exacting questions that emerged from my reading of the text.

“What is its story lines and themes?”

‘This poignant story is about the changing circumstances of Wang Lung whose undying love of the land sustains him through years of hard times. Its subject is the compelling intimacies of life, it’s cyclical nature, the new coming to take the place of the old, the passions and desires that motivate a human being, of good and evil, and the desire to survive and thrive against great odds. This saga traces Wang’s rise from the abject poverty of his early years to later when he accumulates great property and power. Along the way he comes up against some hard facts of life. He observes the extravagant consumption of the indecently rich, contemptuous of the needs of the starvelings, drawing the ire of protesting revolutionaries while armies shanghai civilians, forcing them to carry their materiel and enter the fray.’

‘He takes refuge in his family, I suppose.’

‘The hardest facts to swallow involve his own well to do family. He discovers that rolling up wealth can bring unforeseen vices and woes in its train – blind jealousy, cupidity, selfishness, complacency and profligacy to name a few. Having fallen on hard times his malignant uncle tries to gull him, offering him silver for his possessions at considerably less their value. His eyes are on Wang’s parcel of land. Coming from a stranger this would have been understandable but from a close relative unpardonable. When Wang achieves prosperity himself, his eldest two sons will engage in dispute, the third running away from home. The two eldest assure Wang they will retain the farm upon his demise but we know their real intentions.

“Blood may be thicker than water” commented David, “but also stickier. Money changes people and relationships. Tainted by lucre, the free flow of family love can get really clogged. It can happen in the best of families. Financial transactions involving family members are fraught with danger. It’s a classic recipe for trouble.’

‘Burning down the house to roast the pig.’

‘A breakdown in trust can rent the family asunder. Does this surprise you?”

“Wang’s immediate family was not so different to my father’s, David” I replied. “He and his siblings squabbled about their father’s estate, picking over his properties, him not yet cold, over his freshly dug grave, with accusations of humbug and mismanagement.’

‘Love flies out the door when money comes innuendo.’

‘This let to permanent estrangement between my father and his brother. I daresay this would never happen in our family. We could never put our foot wrong again like this. Moreover, my father’s business has gone to the wall what with the self-service supermarket revolution and his being rendered crippled. So I don’t envision any great bone of contention like this ever arising. We respect him too much not to honour his wishes.”

“I’m glad to hear that Allan. Just bear in mind that family members can have such high expectation of each other and correspondingly such great disappointment. Greater than in other people. In families things are never as simple as what you’d expect.”

“Right you are, David. In my estimate this deceptively simple parable is all about complexity – the complexities of marriage, parenthood, joy and human frailty. What I could not have known while giving such utterance was that this would be a leitmotiv I too would pursue one day. Looking back on my own saga, in my own book.”

“What else did you tell her?” asked David.

“I congratulated her for broadening the reach of literature, making asian voices heard for the first time in western literature. For opening a faraway and foreign world to deeper human insight and sympathy. For highlighting the role of women.

In China’s patriarchal culture, wives were forbidden to speak unless spoken to. Her principal subjects – women and China – have too long been peripheral.

I thanked her for not shying away from matters considered taboo in my own schooling – matters concerning bodily functions, particularly sex that she approached, like the Chinese with a healthy candour. Her novel’s unvarnished talk of these matters disturbed some delicate sensibilities. One Presbyterian pastor said it should have been titled “The Dirty Mud.”

I thanked her for raising questions such as abortion and family planning, unsettling as these may have been for the official custodians of the moral status quo.

I saluted her for helping prepare us in the thirties to consider the Chinese as allies in the coming war with Japan and for supporting their struggle both in her public rhetoric and in books. For drawing attention to failures in this respect so that we can learn from them. In “The Promise” she touched on the incompetence of the British and their lack of concern for their Chinese allies. Basing her story on historical fact, she recounts how retreating British troops crossed a bridge and scuppered it, leaving the Chinese behind to be massacred. She had warned Roosevelt that Churchill’s insistence on preserving an empire in the East would hamper the war effort.

I thanked her for using her personal influence to prepare us to institute normal relations with the People’s Republic of China, a stance that like her earlier expression of Sino-Western solidarity, would have important strategic implications.”

“You are aware Allan, that not everyone has such kind things to say about her. She has fallen out of critical favour for different reasons. Some turned up their noses at her when she received the Nobel prize, claiming her work fell short of the stature and complexity worth of such recognition. Admittedly the quality of her work is patchy which is what you’d expect from someone who writes so abundantly. But we have to look at her overall contribution. Hers is an extremely valuable body of work that merits closer examination if only because of her wide popularity,” he said.

“You’ve put your finger on it, David. ‘I put it to Pearl that some high-brows who sniffle at her work do so from an attitude of sour grapes, that they may be envious of her success. That Chinese intellectuals never embraced “The Good Earth,” resentful perhaps that an American was exploring aspects of Chinese life they’d neglected. That the literary judgement of American intellectuals is clouded by the tight political climate still in force in which it is difficult to mention China in a positive light.’

‘She came under scrutiny in the McCarthyite United States as an alleged communist sympathizer.’

‘Paltry, hostile innuendo has been dished on her in the West. It is difficult for mainland Chinese to mention the West in a positive light.’

‘At the same time Pearl gained the obloquy of the Party for her ‘petty bourgeois’ background and subjects, for being a ‘reactionary’ proponent of American cultural imperialism, for exposing too much of China’s darker, uglier aspects, denigrating the New China and putting down the fieldworkers.’

‘She must be doing something right. She can’t seem to please either camp.’

‘Under Mao Tse Tung today, her work is banned. Pearl had criticized him by name in the 1950s and, even worse, had invited to the United States an actress who had once been chosen over Mao’s wife for a starring movie role.’”

‘This all sounds very vulgar, infantile and dogmatic,’ I commented.

‘They would have bristled at her depicting the practices of feudal society. I guess the thoughts of Wen Chang, Chu-I and other Confucian sages are out of favour’.

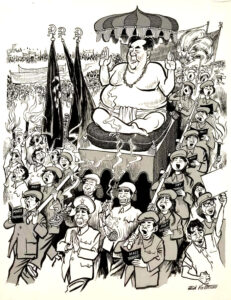

‘It’s all about the thoughts of The Great Helmsman, the wellspring of all wisdom’, David said bitingly. ‘The Godhead who is worshipped accordingly.’

The East Is Red.

We continued this discussion soon after one morning at breakfast. The cook had referred to me the latest breakfast addition-stewed pears. There had been a glut of the crop and stewing them was the best solution.

‘As for a person’s background being an obstacle to a country’s progress, come off the grass. All industrial and commercial concerns have been nationalized, thus making good on the revolution’s economic promise. Why all this infantile hysteria?’ I asked.

‘Why don’t we put this question to Dr. Ward’ he said, nodding his head towards him ‘Are you free, Russel?’

‘You know I’m always free for you, David.’

Dr. Ward motioned to me that I should join him too. Tearing open his packet of Weet Bix, he gathered his thoughts and gave his interpretation of this monumental motion of the masses.

‘I used to write captions for the series of cards you find in these cereal boxes,’he said. ‘Enticing more childish demands for these cards which put the price up as well as the roughage. The series was titled ‘Wonders of the Pacific’.

‘You presumably wrote one titled ‘The East Is Red’: A quarter of the worlds population away from capitalist control being led by the peasantry rather than the expected proletariat’, I joshed.

‘I don’t think so’, Allan, he said. ‘Look at the manufacturer’s name,’ he said, holding up the the packet. The Sanitarium Health Food Company. The holy corporation whose fundamentalist owners still hold that God’s seven day labour of creation ended at 9 o’clock on the dot in the morning one day in the year 4004. Need I say more?

‘Just about childish demands in China,’ I said.

‘Allan, After the initial victory of the people’s revolutionary forces the Party was faced with a serious question: what can be done to keep on the “socialist road”? What measures can be taken to restrict the class differences inherited from the old society, fend off imperialist hostility and intervention, and prevent a new capitalist class from developing within socialist society itself? Socialist revolution is much more complex and scabrous than most revolutionaries have hitherto supposed. The seizure of power is only the first step in a protracted revolutionary process. The Soviet experience bears this out.’

’What’s with this process right now’ I asked.

‘The various factions of the Communist Party are locked into a power struggle on how to resolve this. You have to bear in mind that the Maoist leadership does not permit any direct information to filter out about it’s real motives and the opinions of its various adversaries. The cultural revolution underway at present is an inward looking ultra-leftist campaign, an eruption of elementary forces.’

‘Who does it target?’

‘It’s directed specifically against the ‘Four Olds’: old ideas, old culture, old customs and old habits. Feeling China bogged down by the ideological weight of it’s past, Mao launched it to revitalise what he sees as revolutionary zeal and ideological purity at a time of great social tensions. You’ve seen pictures of those long open mass panoplies of loyalty where he calls on those waving the Little Red Book and chanting hoarse slogans to take on the toughness necessary for action’.

‘Bladders of steel’, for starters’, I suggested, ‘Tie a knot in it when caught short.’

‘The view of Mao’s and his supporters is that, in a socialist society, new generations have to experience the process of revolution themselves, to think through for themselves what kind of society they want, who opposes that vision, and how to struggle against those forces.’

All genuine knowledge originates in direct experience’

‘That’s where he brings in the metaphor of a pear, isn’t it,’ I said, raising a heaping spoonful of the stewed variety to my mouth. ‘If you want to know the taste of a pear, you must change the pear by eating it yourself.’

They look very appetizing,’ Russel said. How do they taste?’

‘Even better’, I said. They’ve got honey and cinnamon. You wouldn’t know that just looking at them of course. Stewing them is an excellent option for overripe pears, as the method works well with their texture.’

’So by mobilising the idealistic youth against a powerfully entrenched bureaucracy,’ Russel continued, ‘he is able to appeal over the heads of these cadres to the wide masses. To mobilize this youth all that was needed was to close down the schools.’

‘And keep the bureaucracy stewing in what he considered a country over ripe for continued revolution. What about the workers?’ I asked.

‘Mobilizing the workers on the same scale and for the same period would have meant disorganizing and even halting industrial production. Being less politicalized than the vanguard workers, particularly those who were members of the Communist Party, these young camp followers are easier to indoctrinate in a narrow factional way. They accept more readily certain accusations against long-standing leaders of the party and the state than would be the case with the workers, who still retain memories of the history of the revolution.

‘So it’s not only their bodies that are softer’, I commented.

‘This may be true but together they can share and act on fierce feelings of resentment. It’s hardly difficult to incite a feeling of revolt against the bureaucrats in this youth. It’s demagogy corresponds to their needs. For the mass of the youth, a professional career seems blocked, the number of positions in the entire state sector being limited.

‘Is it good or bad?’ I asked.

‘It’s considered destructive by some and as constructive by others, depending on their understanding of the current problems confronting the Chinese revolution. Without a doubt things have gotten out of hand. China seems a society where disruption seems to exist for its own sake. There have been terrible excesses. Some have destroyed valuable works of the feudal past-books, temples, antiques.’

‘Bulls in the china shop,’ I suggested.’

‘It’s been said before the Cultural Revolution everyone lived on the edge of a cliff.’

‘And after the Revolution’

‘They took a giant leap forward.’

‘The Party has come up with some interesting slogans like that one, hasn’t it.’

‘It’s their chief mode of communication. For those with ploughs to pull, steel to manufacture, nothing gets the point across like a good slogan.’

‘Can you think of any?’

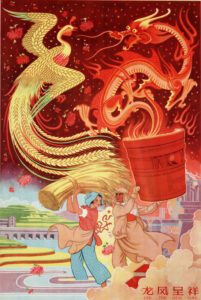

‘Prosperity is brought forward by the dragon and the phoenix.’

‘These creatures traditionally serve as auspicious symbols, don’t they.’

‘They are used to herald a glorious period for the people and the country. This is reflected in the Chinese saying: “When the dragon soars and the phoenix dances, the people will enjoy happiness for years, bringing peace and tranquillity to all under heaven.”‘

‘They could certainly do with some now. Any other striking slogans you recall?’

‘One of the most mouthed slogans features the phrase “nothing can stand without destruction”, encouraging destruction of old, feudal things.

‘I’d like your two bob’s worth on this, Russel ‘I said.

‘It’s a variant of ‘you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs’, said Russel.’ Whether the eggs are cooked or otherwise, it doesn’t matter. Do you see your way clear to making this goog stand upright?” he asked, handing me a boiled one.

After grappling with it for several minutes, I still drew a blank, so giving in, I said, ‘Your point is well taken. What’s the solution?’

“Elementary my dear Watson,” said Russel, grinning, as he forcefully smashed the egg down into the table. “Chairman Mao has said, ‘nothing can stand without destruction,’” said this seditious sage, “look, isn’t the egg standing upright now?”

So it was. No flies on him, he had made his point about this tomfoolery. Many a true word is spoken in jest.

‘As things stand, in this free for all anyone can be targeted to meet the quota, excoriated as ideologically shonky,’ he went on, ‘arraigned for being ‘running dogs’, ‘capitalist roaders’, ‘rightist devils’ and ‘enemies of the people’. This has even included prominent Party leaders such as Deng Xiaoping. There’s a story circulating about his rapidly changing fortunes. Three men are in jail comparing their reasons for being incarcerated. The first says: ‘I’m in here for being a supporter of Deng Xiaoping.’

The second replies, ‘That’s funny, I’m in here for attacking Deng Xiaoping!’ The two turned to ask the third, ‘What are you in for?’ Shaking his head sadly, he replied ‘I AM Deng Xiaoping.’

These prisoners were there so long that they had started giving numbers to all the old jokes and just shouting out the number without telling the whole long story.’

‘It must have sounded like inside the kitchen of a Chinese restaurant.’

‘You could say that. Deng Xiaoping would shout out for example, ‘Number 31’ and the others would howl with laughter.

But when one fellow called out ‘26!’ hardly anyone laughed. The new guy said, what gives, why didn’t anybody laugh?

‘Well,’ said one long termer, ‘some guys just can’t tell a joke.’

‘Systems of repression create inherently amusing situations, don’t they’

‘These can even get to the repressors. There’s a joke about the time Walter Ulbricht met the Chinese Premier.

‘Have you a hobby, Herr Ulbricht?’

‘Yes, I collect jokes that people tell about me,’ says Ulbricht. ‘and you?’

‘Oh, I collect people who tell jokes about me,’ says the Premier.

‘If this repression can happen to leaders with such prestige as Deng, what hope is there for ordinary people?’

‘Such class ‘labelling’ even involves pre-school children. Some teachers and officials have had their homes muscled in on, been dragged into the streets before ad hoc crowds of insulting Red Guards, trumpeting their revolutionary virtue. The mobs that roam through the streets, sticking up posters and shouting slogans, need not necessarily come from outside. They’re as often as not ordinary jolly people trying to be good citizens, at some level simply trying to do the right thing. Parading their neighbours like prisoners in the streets with dunce caps or shaven heads and subjecting them to public self-criticism meetings and all-night “struggle sessions.” Many of these targets may have had faults such as authoritarianism towards students, attitudes of superiority towards workers and peasants and so on and so forth. Like everyone they should be open to questioning. But public humiliation is not the right cure for these blemishes. And teachers may also have been targeted, not because of their faults, but because they were potentially articulate critics of the ‘Great Teacher’s’ policies.

‘It appears their fanatical inquisitors are very shy of the very freedom of thought and of academic inquiry they accuse the university president of,’ I commented. ‘I can just imagine how would this have gone down with workers’.

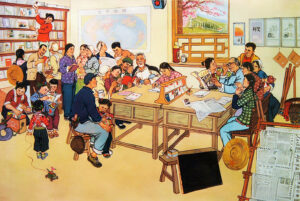

‘I don’t think by any stretch of the imagination many workers would feel at ease about the po-faced preaching remedies of runny nosed, fuzzy lipped snotty kids,’ Russel said. ‘At the same time there have been positive signs. At street level one rationale of the program is rooted supposedly in the notion that “bourgeois intellectuals” will be re-educated through physical labour, and that young people in the urban areas will be integrated with the rural peasant population. The most obvious success has been the re-settling of medicos in the countryside. They have trained 750,000 “barefoot doctors” – thereby narrowing the gap between urban and rural medical services. Most sent to live to the countryside and learn how the peasant works and lives, discarding the vanity and sense of superiority typical of city folks and become more down to earth.’

‘That sounds reasonable’ I said, ‘It will toughen them up. As long as they want to go, and both them and the peasants benefit, their children having better educational opportunities, their minds opened to a wider world beyond the village.

Otherwise China’s enemies will say it’s just brainwashing.’

‘Those who believe that an army of robots is being completely guided and channelled by remote control are greatly deluded,’ Russel continued. ‘Facts demonstrate incontestably that there is a very great diversity of opinions, a very wide autonomy in action and a harvest of posters, mimeographed or printed papers. People are exercising their rights to freedom of speech and freedom of debate by putting up big character posters in the streets.’

‘The writing’s on the wall. Clear signs that things are going wrong for some people.’

‘Various organizations have been created on the basis of the different ideas bubbling up. Despite the excesses which have been committed and the Mao cult in which the whole movement has been bathed, this harvest of ideas and experiences undoubtedly constitutes an unprecedented experience for thousands of young Chinese. They can end up thinking for themselves. It has led to the rapid resurrection of a critical spirit in a vast mass movement, which cannot not help but thrust thousands of young people on the road toward consciousness regarding the contradictory aspects of Maoist ideology, towards questioning the power of the whole bureaucracy, its Maoist faction included.’

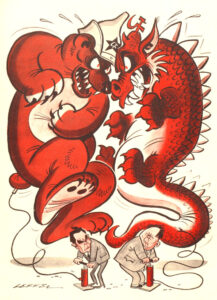

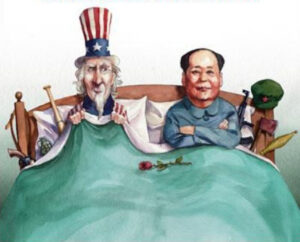

‘Steeped in such a domestic crisis, China doesn’t sound like a country single-mindedly getting on a war footing to invade us, as we are constantly being reminded. Especially when many of its military forces are actually stationed along the border with the Soviet Union ready to fend off a feared invasion from their fellow Communist state.

Those who seem at greatest danger are the Chinese themselves. Where does the West figure in all this?’ I asked.

‘In part, this tumult is a knee-jerk reaction to China’s perceived encirclement by both the US and the U.S.S.R. and threatened encroachment on its territory.’

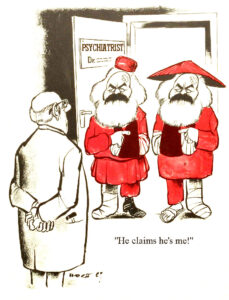

‘And yet both China and the USSR put down their differences to how they interpret the thoughts of Karl Marx. In true fundamentalist fashion they look for evidence in the ideas of a German philosopher and internationalist activist to determine that their country produces the more genuine Communism.’

‘Hostility to foreigners is not a Communist invention. Our peoples have too long been equally ignorant and suspicious of one another. It doesn’t take much to get the xenophobe’s bandwagon rolling’

“There’s only so much mileage in these isolationist approaches”, said David. “They’ll hopefully peter out soon. Both giants will have to chop each other down or come to terms with each other. They’re both too big for the other to ignore.”

Like David, Russel and me, Pearl wanted to see good relations between East and West.

With the rollback of Communism, I dare say they’re closer, confrontational attitudes having softened dramatically, the excesses of the Cultural revolution having ensured it’s shivering polar opposite.

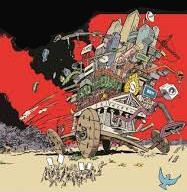

She would have been amazed by the events that have transformed The Middle Kingdom, changing it from a backward feudal country to the industrial workshop of the world, thrusting it onto the centre stage, all within my lifetime.

All fuelled by those values she wrote about – hard work, thrift and responsibility. Values which the West enshrines but fears when they propel the Chinese component of the runaway global economic juggernaut relentlessly forward, it’s engine room firing full speed, its giant wrecking ball swinging wildly, bearing down on us, crushing competition, disembowelling society, poisoning the most intimate human encounters, blindsiding opposition, cracking, hacking and fracking, sacking and whacking, squeezing and freezing, gouging and gobbling up precious resources, slashing and burning, despoiling the good earth of it’s fertility.

It’s tentacles reaching far and wide it now enjoys the position that Britain had when it crushed Bengal’s textile industry and built India’s railways.