Thriving in this secure burgeoning world, thoughtful in all matters of the mind and plenty serious, I whiled away much of my leisure time engrossed in the radio, the picture theatre and books. Once I got into serious reading, my head stuck in the pages, that was it.

I became fascinated with the writers and actors I encountered, and the literary and theatrical sets in which they consorted.

I made the art, creativity and style of these originators fit my purposes.

Giving credit where it’s due, I have incorporated their works. They enabled me to create my own identity, opening a window on the outside world for me. The wide world of thoughts and dreams, myths, ideas, inspirations, intuitions brought into being by the human imagination since the dawn of consciousness.

Not just something decorative, much of the costumery we wear, the songs we sing and so on. More deeply the body of ethical and moral values that we place around each individual to keep at bay the barbaric heart that history teaches us lies beneath the surface of all humans. Our culture that enables us to make sense out of sensation, to find order and meaning in a universe that doesn’t give it freely. The glue that allows civilisation to happen and wards off alienation.

The radio acted to dispel any sense of isolation, being my main source of news, music and entertainment. My first was a crystal set that I was attached to, snuggled up under the bedcovers at night. My same time, same station ritual before getting shuteye. The single family wireless receiver was built like a piece of furniture and took up a whole corner of the lounge room.

Television didn’t become widespread until the end of my schooling, thank goodness, although a number of people picked up Sydney channels once they installed large antennae.

It was left to the ‘theatre of the mind’ to stretch my imagination, letting me create my own mental pictures around what I was listening to. High on my list in this regard were the improvised BBC ‘In All Directions’ and ‘The Goons’ of which I was one of the many listeners throughout the world. These shows featured the talents of the two Peters-Ustinov and Sellers-Britain’s beloved humorists.

It was left to the ‘theatre of the mind’ to stretch my imagination, letting me create my own mental pictures around what I was listening to. High on my list in this regard were the improvised BBC ‘In All Directions’ and ‘The Goons’ of which I was one of the many listeners throughout the world. These shows featured the talents of the two Peters-Ustinov and Sellers-Britain’s beloved humorists.

‘In All Directions’ regarded as a forerunner of the Goon Show featured Peter Ustinov in a Beckettesque road movie, driving round in a perpetual search for Copthorne Avenue.

Peter was a real card who exploited his renowned gift for mimicry to the full. The comedy derived from the characters he and his partner met along the way, often also played by themselves. I aimed to emulate Ustinov’s fine ear for characters and sounds, his perfect command of accent and intonation. I worked at reproducing musical instruments, bird cries in our garden and car impersonations. By taking off his, mine were so accurate that I could get people to leap on to the pavement to avoid being run down by non-existent vehicles. It was my ‘car’s’ cold start one morning that led to my father jumping out of bed, expecting to see his car being driven off.

Such skills could come in handy. Once on a visit to Sydney a trio of louts tried to occupy my seat in a train carriage. I flipped out, acting as if I had been bitten by a rabid dog. This sent them packing.

The Goons’ zany miscellany of skits and bits mixed cockamanie plots with surreal humour, tag lines, quips, cranks, puns and catchphrases. They cooked up lots of ludicrous scripts with an array of daffy and bizarre sound effects.

Their show had no rules.

Appealing to the latent eccentric in me it sharpened my sense of the absurd. The bubbling humour they created also infected the Monty Python team and the Beatles, all who would give me great delectation. It would be the sound of his troublesome stomach that would announce the arrival of the cloddish Major Dennis Bloodnok, a well known coward who deserted from the British Army. This was one of the many characters of Peter Sellers, the impressionists’ impressionist, who could even do a Spike Milligan, his fellow Goon. Peter took on the voice of Hercules Grytpype, a smooth talking con man. He was the twittish boy scout Bluebottle whose flummoxed and flummoxing persiflage with Eccles take place in many of the Goons’ sharp scripts.

At the other end of the age spectrum he was the extraordinarily antediluvian Henry Grun who defies old age and the dreaded lurgy with ‘Get Fat Hormones’. Having lived in India Peter was a master at taking off the broken English Hindi accent through his characters Lalkaka and Banerjee. The Goons’ characters were largely based on dimwits or cads they came across in the forces, or in Peter’s case at a minor public school. With their vocal dexterity their characters took on a life of their own. The Goons was a showcase for Peter’s improvisational talent with he and Milligan perfect foils, sparking ideas and situations off each other. I aimed to capture such clever casualness and off-handedness in my own call and response verbal volleys. Trading banter with partners of the right chemistry, playing off each other’s reactions, feeding a continual flow of fuel.

‘Did you know I invented the echo?’ I asked my mate Owen.

‘Just listen to yourself—self—self,’ he replied, happy to act the foil.

Best Sellers.

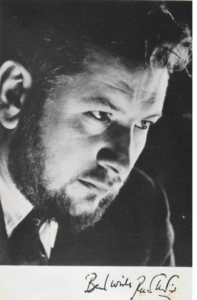

Peter Sellers was one of the worlds greatest character actors, especially in comedy.

This son of struggling vaudevillians was also a very disconsolate man, often infusing his comic characters with an undercurrent of deep melancholy, reflecting his own mood indigo.

This bolstered the belief that often, behind the comic’s jokes, pratfalls and silly voices, there hides a depressed, tortured clown, squeezing laughs from audiences in an attempt to avoid crippling melancholia.

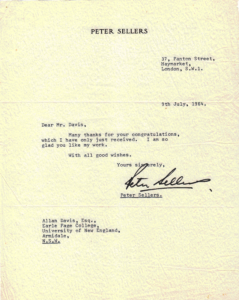

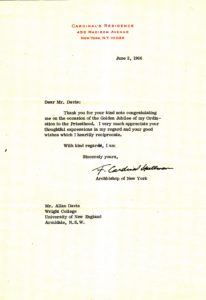

Aiming to help him in a small way overcome his personal insecurities and lack of a well adjusted self-image, I would congratulate him for his comedic legacy for which he thanked me very much.

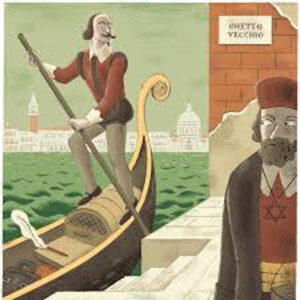

I told this enigmatic figure, who often claimed to have no identity outside the roles that he played, how impressed I was with his astonishing range of characters which had earned him international stardom at a time when rigid typecasting was usual. He had a good nose for playing multiple characters, making the individual characters distinct, frequently with contrasting temperaments and styles, for example in “The Mouse that Roared’ as well as ‘Dr Strangelove’, considered to be his best film. In it, he took on three different roles seamlessly integrated into the end-of-the-world storyline. He had a gift for playing different nationalities and ethnicities. He could embody his characters with such wonderful, ‘out there’ characteristics.When Peter Ustinov dropped out of the role of Inspector Clouseau, Peter Sellers stepped in and made Clouseau his own.

Peter strove to avoid playing the same character twice. He especially enjoyed slip-sliding into characters much older than himself. He could slip in and out of characters as easily as one slips in and out of a jacket.

In Lolita as a mentally unbalanced TV writer with multiple personalities he mined emotional depths and reached crazed comic epiphanies unmatched in his later work. Playing what could have been a subordinate role, he steals the movie. His hotel porch confrontation with James Mason’s Humbert Humbert is a marvel of nervous energy and quirky timing.

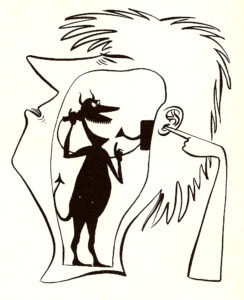

He played three of the roles in the Cold War satire, ‘Dr. Strangelove’ including the wild haired, menacing scientist.

Watching him I became aware of that sense of lunacy lurking. You never knew when his role would be as someone provocative, sensible, totally insane, singing, shaking his booty or exploding. He was a unique combination of being extremely subtle and over-the-top all at the same time.

A Man Of Capacious Talent.

I congratulated actor, raconteur and humanitarian Peter Ustinov for adding to the public stock of harmless pleasure with some darned good acting thrown in for good measure. I told him, ‘You have enriched the gaiety of nations. Good for you.’

As an actor, he won international stardom as a lurid, gloating Nero in the 1951 epic ”Quo Vadis?,” gained increasing stature by playing sly rogues and became one of the few character actors to hold star status for decades, adjusting easily to movies, plays, broadcast roles and talk shows, which he enlivened with pungent one-liners and hilarious imitations. I told him he was far from being an epigone. This was no faint praise.

I congratulated him in particular for his portrayal of the slave owner Lentulus Batiatus in another sword-and-sandal epic, Stanley Kubrick’s ‘Spartacus’ which brought him the first of two supporting actor Oscars.

As the unctuous self-disparaging slave dealing Lentulus Batiatus, purveying shapely females to the Roman upper classes, owner of a gladiatorial school, his instructions were to bully Spartacus mercilessly and break his spirit. Fellow actors still analyse the almost throwaway technique of understatement with which he upstaged Laurence Olivier during that player’s prime.

Peter sent me his best wishes from the Lake Geneva area.

He lived there in his later years along with his friends and neighbours, Graham Greene and Charlie Chaplin.

Avid readers of the latter’s novels, Charlie, Peter and I couldn’t get enough Greenes in our diet.

Peter’s acting career was characterized by numerous roles in which he displayed those talents for vocal mimicry and age affectation. In 1946 he played the detective, twice his own age, opposite John Gielgud in a legendary stage version of Dostoevsky’s Crime And Punishment.

The Big Smoke.

“He ceased; but left so pleasing on the ear his voice, that list’ning still they seemed to hear.”

Homer, describing Odysseus’ effect on an audience in a faraway land.

As a child I came to Sydney during school holidays and other times to stay with my father’s sisters. I got to range over this big city, especially its centre, on my own hook. Like most people I like to watch the activities on building sites. This particular one I came across in November, 1960, just a stone’s throw from Circular Quay, my reference point, was not like any other. This was where the latest wonder of the world was being constructed. The Sydney Opera House. I asked one of the hardhats entering a gate how I could get approval for a look-see.

‘How far have you worked up those tricky sails structures?’

‘Listen Sonny Jim,’ he said hurriedly, hugging an oxy acetylene cylinder, ‘after a slow start, I can assure you now we’re cooking with gas. Come and see for yourself. The opening act is just about to start. If you want to see and hear a world class act, just tag along with me. You can do the official tour anytime.’

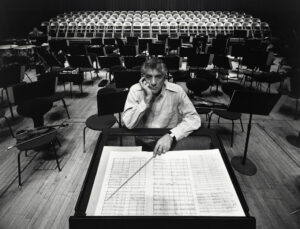

Was he fair dinkum or having me on? Curious as to what kind of artistic performance this labouring man could offer, I decided to take him up on it. He led me through a maze of massive concrete slabs, building machinery and the general clutter of a construction site, onto the performance space – this stupendous expanse of concrete platform, resembling an ancient Mayan temple, decorated with cranes. Workers were standing, sitting on their haunches or perched on the scaffolding eating their lunch, gathered around a burly, imposing black man of commanding presence. He spoke slowly and deliberately and with force. We were all hushed, spellbound as this extraordinary beautiful, deep, rich, bass-baritone set of pipes, as calm as the water lapping around the site, then began to boom.

Bowled over by the sheer magnitude of the notes his lungs and diaphragm expelled, I realized his stirring voice must have carried far beyond. He would have been heard from miles away. His singing without accompaniment lent a highly personal atmosphere to this impromptu standout performance. I recognized the voice as soon as it opened up. There was only one in the world like that – Paul Robeson. Except that when he broke into Old Man River, he had changed the lyrics, ‘ No more “tired of livin’, scared of dyin’”, to “must keep fightin’ until I’m dyin’.

He sang the stirring song of protest ‘Joe Hill’, about the unionist/songwriter.

Joe was summarily executed for murder, many believe on trumped up charges.

In the song Joe who had supported strikes by rail workers is remembered as an inspiration who lives on.

So powerful in the directness and simplicity of its melody and lyrics.

Paul sang that “what they could never kill went on to organize.”

In his rendition it became a moving hymn to the never-ending struggle of working people for justice.

It closed with the words “Don’t mourn for me, but live for freedom’s cause.” Goose flesh manifested.

Rising to our feet we rewarded him with our extraordinary attentiveness and warm-hearted response. These construction workers raised the roof.

There was just something, that drew these workers and Paul Robeson together. I think it was like a love affair, in a way And that seemed entirely right.

At the end of the impactful performance Paul met and talked to us well-wishers.Those eager to speak to him at the end asked questions to learn more about his life. We gave moving remarks on how we were motivated by his commitment.

While escorting me outside my host explained to me the nature of this event:

‘Our trade union invited Paul to come here today. He can perform anywhere he likes-in palaces, in grand theatres, but he prefers to play directly to the people he believes in – those who earn their bread by honest toil – the common people. He sees us as truly brothers and sisters in the great family of mankind. Like Joe Hill did, Paul sings at union meetings, on corners and picket lines, to us. Although we are the ones who build this mighty structure, we know we won’t be the ones who’ll be able to afford it. So this is a once in a lifetime occasion for us. For an hour at least we’re the ones who call the tune.’

The Soundtrack of my Youth

At the beginning of the 60’s I entered a musical quiz broadcast by the mobile studio of the local radio station 2MO at the local show. As a kid, I was chuffed to win against a local schoolteacher and to receive something that was brand new to the world – a transistor radio. This breaking of the nexus between the radio and the power point was an exciting development. It brought with it a profound increase in the exchange of knowledge, ideas, and information, which in turn influenced my generation to become more of a going concern in politics and other affairs which affected us, than what our preceding generations would have been. Wrapped around my ear, it provided me with a companion to fend off boredom wherever I was and to lay on background music for whatever mood I wanted. With my ear to the ground, twiddling with that dial, I was well and truly switched on.

This revolution in listening consummated the age of fast expanding mass media whose birth coincided with mine. The baby boom and economic growth had fuelled the emergence of the youth culture I grew up in. I wondered what had happened to the big famous big swing bands that had come before. The leader of the local brass band, Iven Laing filled me in on this.

‘Allan,’ he said, ‘it costs a bomb running a small town band. Imagine how more so it is for big bands. The big professional ones had to cash in their chips. During and immediately after the war bandleaders became balled up and chained down with big musical units. With shortages of fuel and limitations on audiences and available personnel, they became uneconomical. Many musicians felt it impractical to carry on this tradition. The big bands were replaced by smaller combos, using electric guitars, bass and drums, amplifiers and microphones, producing 45 rpm records. What’s transforming the musical soundscape now is rhythm and blues from the inner-city ghettos exerting itself in various forms.’

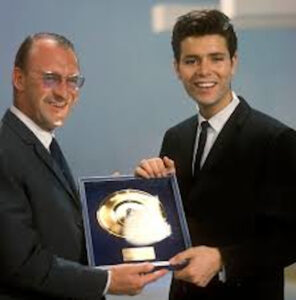

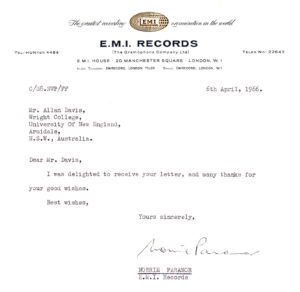

Those with an eye for tapping into the huge emerging market that accompanied these changes knew the importance of the means of communication. Of course, it was forces stateside who ushered in the birth of the rapidly growing popular music industry to shape my listening. One of those responsible for nurturing it on the British side of the Atlantic was Norrie Paramor, head honcho of recording for the giant EMI Corporation. He had a head both for music and the industry. His background as composer of movie soundtracks, arranger and orchestral conductor, enabled him to become one of the top producers of easy listening and early British rock and roll. He played a large part in determining what I and millions listened to before the Beatles rage. Norrie arranged and produced recordings by such artists as Eddie Calvert, Helen Shapiro, Britain’s answer to Brenda Lee, and the star turn of his stable, Cliff Richard, a knight to Elvis’ King. He was musical director for the legendary Judy Garland when she lived in London.

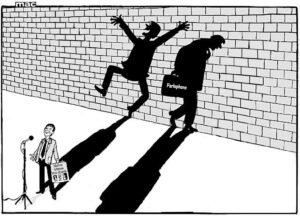

Norrie had an ongoing rivalry with George Martin, his opposite number at EMI sister label Parlophone, who had under his wing amongst others the comic talent of Peter Sellers. George was trailing Norrie in the number of hits they produced, largely due to due to the popularity of Cliff and the Shadows.

Martin seethed as Paramor racked up 26 weeks at No 1 during 1962.

‘He drove an E-Type Jag,’ Martin remembered. “It didn’t matter what they recorded, it could have been God Save the Queen, [but it] became No 1. I envied that.’

Cliff and George kept their delight and disappointment respectively about this success hidden but the Shadows couldn’t hide it.

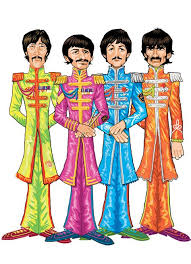

Then the tables were turned. George struck it rich. Helen Shapiro’s supporting act, the four mop topped lads from Liverpool came to George’s notice. This once in a generation sensation would sweep the field, but not before parodying the ‘Shadows’ in their instrumental ‘Cry for a Shadow’.

Every dog has his day and as I would remind Norrie, he had had his fair whack. I told him to take the Beatles send up as a back handed tribute. He was delighted to learn of the enjoyment he and his protégés gave me in what would seem, at least to many mums and dads looking back, an oh-so-squeaky-clean age when the sound was toned down and records kept ‘straight’.

Surf’s Up.

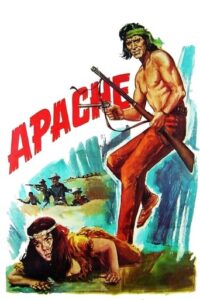

I told Norrie how thrilled I was by the instrumental smash hit ‘Apache’, performed by Cliff and his backing group The Shadows, which Norrie put together. A pioneering example of the surf music genre with its use of twangy guitars, its innovative tribal rhythms and straightforward melody, it evoked that mighty rush I felt, the swells coming fast, hooked onto the forces of nature while surfing. Body surfing that is. Being fair freckled skin and a country mile from the salty tang of seawater, I had as scant a connection with the lifestyle of those archetypal bronzed briny boarders who hung five, hugging the coast, as had those melody making pommy palefaces.

Burt Lancaster’s tribal leader in the movie ‘Apache’ likewise had no connection with the ocean. It was his courage that inspired the tune.

It was my own courage that came into question when I dipped my toes into the ocean. My problem with spending much time in the water was that sharks decided that that’s where they should be. I didn’t want to offer myself as a light snack. I would eventually go to the beach with my friend Neil Proudfoot to try board surfing. He kept encouraging me, ‘You coming in, Allan? Come into my maritime manor. Come and shoot the curl. It’s lovely in the water today. You can’t ride a board on the beach.’

‘No, I don’t think so. I’ll be– I’ll be fine.’

‘Why not?’

‘Why not? Because there are sharks in there. It’s their natural habitat.’

‘Yeah. But not always.’

‘The fact that there’s ever been one is enough for me.’

‘Ah, come on, Allan. You’ve got to live your life.’

‘Yes, until it ends. Maybe today, with a shark attack, you see?’

He said, ‘You’ve got more chance of being hit by a car.’

‘Not when I’m swimming, I don’t. I’ll stay here on the beach until I summon up the courage.’ I stayed right there until the heat out threatened the sharks.

That’s when a new menace threatened those in the water. Me. While Neil glided gracefully behind me, at one with with his wave, I was at two with mine. Somehow I had changed from boardsurfing to bodysurfing.

And the body wasn’t mine.

Put a Penny in It!

Going to ‘the flicks’ was undoubtedly the most enjoyable time of the week. This young movie buff got to go twice a week to this darkened sanctuary. During the week I would go with my parents. Everyone one went to see the same films. We would sit on the comfy cushioned chairs upstairs in the dress circle and see two feature films. I would stay behind at the end to collect the lemonade bottles which people left on the floor, along with their sweet papers and tickets. Sitting in the dark with others watching a screen somehow is conducive to that habit which is defiant to the cultural standard of cleaning up after oneself. The deposits on the bottles which patrons paid and which I would claim paid for my night out plus my Saturday afternoon matinee. This was a more rambunctious affair, sitting on the harder stalls down below with orange coated chocolate balls and the groundlings hissing, booing or rolling in the aisles. ‘Hey, down in front!’ How anyone could hear the films was a mystery.

A chorus of finger whistles and voices would punctuate the silence like a dose of salts when the projector conked out with slow handclapping and catcalls of ‘put a penny in it!”

The owner of the picture show would walk up and down the aisles flourishing a torch to shine on anyone too excited to watch the show. This was the best opportunity to sneak in by the side door he left unguarded.

We kept our eyes out especially with the arrival of Cinemascope .

When interval came there was a rush for the toilets and refreshments. Otherwise you could stay and watch the advertising slides. Passouts were given to those who wanted to leave the building. After the dark interior inside hitting the street was like running into a flash of lightning. If you made it back late, you’d have to feel your way back to your seat, falling over legs, getting kicked in the shins and tripped up, squeezing past those already seated shushing and saying, ‘Watch where you’re going’, mind out’ and ‘this is not your seat’.

Defining our fantasies, fears and pleasures, most of the films were American.

These were followed by British and a dwindling number of locally made films. The American cinema told stories that identify a collective fear of invasion, nuclear destruction, and invasive political ideologies, reflecting this paranoia back to a receptive public.

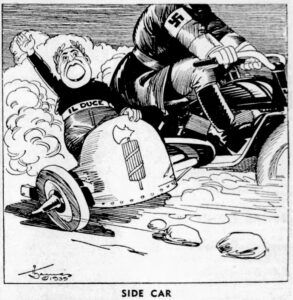

I Married a Communist is an example of this Cold War propaganda . It combines standard film noir plotlines – hidden pasts, personal failings and doomed relationships – with unsubtle political warnings about subversive communists, troublesome unions and their alleged secret agenda.

After it was announced it was “Them! Them! Them!”, the eponymous mutated, giant, radio-active, murderous ants hatched in the New Mexico desert after an A-bomb test were interpreted as Communists on-the-loose.

It was a toss-up whether the police in American noir were corrupt or not, but in British films of the 40s and 50s, corruption was startlingly absent thanks to censorship. Policemen were portrayed both sympathetically and impeccably as hard-working, caring, humane individuals while the crims were unstable delinquents on the make who got their just desserts. Forget tasers, SWAT teams, air marshals, finger printing brutal interrogations, strip searches or indeed any hint that policemen are less than saints in uniform. In the Ealing films London police, their hearts in the right place, rode bicycles, directed traffic, gave directions, found lost dogs, and even sang in the police choir. The grossest sin committed by the police was a tendency to park themselves in the police cafeteria and drink one too many cups of tea.

Sentimental viewers today may fall for the idea that these movies showed a gentler, kinder age. More cynical viewers (including yours truly) understand that they are a reflection of the age and its censorship. Not too surprising as the Harriet and Ozzie world in these films did nothing to offend. Generally these movies endorsed the idea that the police and military apparatus made us secure, standing between us and the End of Civilization as we know it.

At the end of every show the lights came on and God save The Queen was played. Everyone stood in silence while on the screen appeared Her Majesty and Phil the Greek. If you didn’t stand someone would remind you with a prod in the side. Most of us didn’t know all the words and just mumbled along after the opening lines.

This was a particularly barren point of time for the Australian film industry. The hunger for local people to see their own stories on the screen was voracious. They were nostalgic for a time of hardy pioneers. When the classic ‘On Our Selection’ film featuring the rustic Dad and Dave came to the pleasure dome, the queue to buy tickets stretched along Conadilly Street, the main drag. Usually the only Australian content of the program was the newsreels, as often as not giving the latest update on the ongoing ‘war between good and evil’, on the battle against the ‘Reds’ for world mastery. Kicking off the matinee performance was the American serial with its ham acting and crude special effects, laughable today, but gripping stuff for us kids then. A variety of short films of topical interest and cartoons would provide filler until the main item started rolling.

The feature films of the fifties overwhelmingly reflected conservative values with white-bread social, gender and racial roles being promoted. Men were men and women’s place was in the home.

Any African Americans looned around and popped their eyes while playing maids, servants and crazy legged dancers. The ‘natives’ in the Tarzan and Jungle Jim films were usually relegated to romantic backdrops to be exploited by civilized white men or eaten by wild animals. Or they formed implacable hordes, red in tooth and claw, who only understood the language of force.

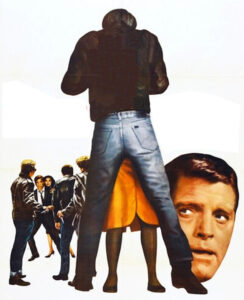

Occasional outbursts of defiance and rebelliousness as portrayed by individuals if not by organized political groups made it through to the Civic Theatre in Gunnedah. These were conveyed in films such as The Wild One, Rebel Without a Cause, Blackboard Jungle and The Young Savages. Performances by Marlon Brando and James Dean as contemporary anti-heroes added some reel biff to a fairly long period of sanitised run of the mill releases.

They examined the topic of juvenile delinquency, one in which American independent film-makers had already taken an interest.

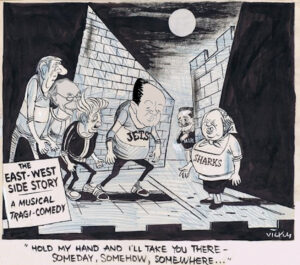

It is the subject of the hard-hitting street gang murder thriller ‘The Young Savages’. It’s a dramatic companion piece to “West Side Story without the music and romance.

Burt Lancaster’s cinematic character, the Assistant D.A. has to solve a disturbing, horrific murder case .

The main focus of attention, composed and controlled, honest and impassioned, Burt delivers a typically solid performance . He nicely balances sensitivity and concern with his patented macho bluster.

With brilliant camera work the film would influence the later work of Scorcese.

Coming out at the end of the conservative and seemingly blissful 50s, I was not used to watching such shockingly raw depictions of racial tensions, bigotry and public servants putting their ambitions before justice.

It helped me understand the social conditions driving youth to violence. I was interested not just in how the intrepid attorney solved a criminal mystery but how he sought to uncover the psychological reasons behind the defendants’ reprehensible actions.

What he learned humanized these young killers without absolving them of responsibility.

Examining similar themes as ‘West Side Story’, the more noteworthy release of 1961, The Young Savages is part “social conscience” film, part court-room drama.

Unlike the colourfully aestheticised take on gang warfare on the Lower East Side of NYC, ‘The Young Savages’ is more introspective as It aspires to be a revealingly realistic insight into juvenile delinquency, a topic in which American independent film-makers had already taken an interest, their works making their way to my local cinema. Often brandishing a tough, uncompromising edge, ‘The Young Savages’ strives to solve a social problem many cities still grapple with today.

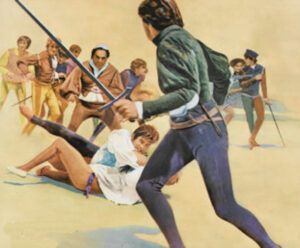

At the same time, complete with Italian and Puerto Rican gangs facing off, fights and foot-chases , it catches the wild fury of gang pavement and alley warfare in the rough asphalt jungle of Harlem, dominated by dog-eat-dog sensibilities, and sneering youth finding a better fit among peers than at home.

The civil war is all about defending ones turf. Opening in much the same stirring manner as the Oscar-winning musical, ‘The Young Savages’ sets up a showdown between two rival gangs in the New York City slums. Three Italian teens, members of a gang called the Thunderbirds, dressed in black leather jackets and roll up jeans cross over from their Harlem Italian neighbourhood and angrily storm into Spanish Harlem.

The members of each posse have been willingly brainwashed by a warped code of ethics and predatory mentality since they first ventured onto the city’s dangerous streets, and both groups harbour a mutual hatred based on ethnicity alone.

Burt’s character has to deal with these hooligans while at the same time protecting his socialite wife from their attack.

On the screen I had seen endless legions of American Indians mowed down to expand the frontier of civilization. When the cavalry won it was a great victory, and when the Indians won it was a massacre.

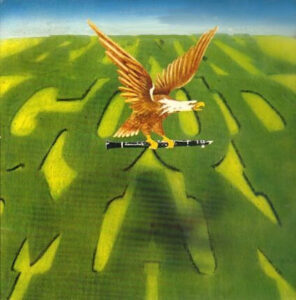

I told Burt Lancaster it was an eye-opener for me to see him interpret their plight as the result of white conquest and displacement rather than the result of their own ignorance and barbarism. While typically still using non-Indian actors for such roles, ‘Apache’ was one of the first films to depict the Indians sympathetically and one of the liveliest. A dazzling frame for non stop action, the film is full of spectacular battles, breath-taking chases and tight suspense.

Burt took on the persona of the renegade Apache, Massai.

Fired by his exploits I in turn envisaged myself as this indomitable warrior of sorts. Refusing to be treated as a slave and being forced to kill others. Refusing to accept the kind of humiliating surrender that Massai’s chief Geronimo had submitted to after years of bloody fighting with settlers.

Going native, I horn in on the surrender ceremony in mid-stream to hurl defiance at the top dogs. Cut to the the prison train I‘m transported in. I make a break for it to undergo an epic journey back to my home. With unflinching strength and enormous cunning, I wage a one man war against the US cavalry. Scampering over rocks and rolling unscathed between the wheels of racing wagons, I squeak through. I keep one step ahead of the highly trained soldiers, riding the skin off their foaming horses, pounding the prairie, raising a cloud of yellow dust. They have sworn to track me down. As my resistance escalates into a final show- down, I know I must persevere, not only for my own life, but for the pride of my people.

This the cinematic warrior does, for the sake of the film studio who wanted a happy ending, against Burt’s wishes. The historical Massai was brought to bay by the cavalry and cut down. It seems we could only have our eyes opened so much at a time.

A Question of Colour

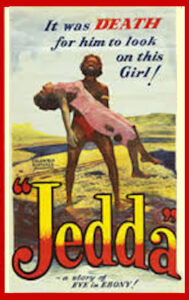

Another film that impacted on this young cineaste during the period was “Jedda”.

I remember the posters outside the picture theatre announcing it’s coming. Interest in them was off the charts.

The straplines read “The magic of the native mating call was stranger than the habits of civilization” and “The drama of a girl caught between civilization and the call of her native instincts”.

Such words acted to stir the blood of the local people. This wasn’t another feel good movie with Doris Day. ‘Jedda’ was daring, long awaited and duly well patronized. It was the first Australian feature film in colour and the first in which the indigenous cast played themselves. Colour was an important element because the film dealt with the question of skin colour, still then an important determinant of one’s status in a racially divided Australian society. At the premiere in Darwin, first nation people were kept separate from the white folks. Only the two stars could sit upstairs in the comfy seats. At its first showing at the Civic Theatre in Gunnedah, I sat downstairs in the stalls with my nanny, Rose who took me as my parents were flat to the boards renovating our shop.

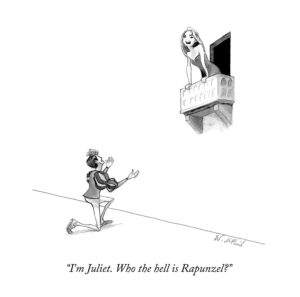

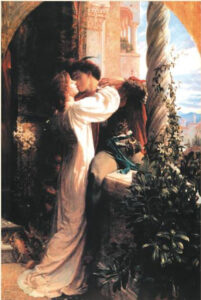

Turning on the aboriginal stars, the film was the first to give considerable weight to their emotional lives. Marbuck is the tribal young blood in this outback take on the Romeo and Juliet star crossed lovers scenario. He is dignified and proud, ignoring the castoff trappings of civilization. He’s not wearing trousers like the other Aboriginal men, and he never puts those dacks on. He is introduced at the beginning as a problematic outcast. He makes an entrance to the station and is told by the owner to leave and camp away from everyone else. When he is shooed off, he’s being shunned, but his egress is also a marvellous entrance and we see about four different shots of his handsome body. Jedda, the object of his desire is a young woman who was taken in and adopted as a baby by a white family.

She learns how to read, write and dress like a white girl

and is steered towards white tendencies and away from first nation norms.

Yet she feels an increasing sense of solitude

She feels more and more fascinated by the tribal life style.

Unlike the case of Rose Watley, this lifestyle draws her to it. It remained intact much longer in the northern territory of Australia. Jedda, who longs to go on the walkabout every year, hears tribal chants over her European piano. She is torn between two races and cultures.

It is Marbuck’s mating call that entrances her and stirs her awakening as a woman.

He takes delight in tearing down the wall that the mission has erected around her heart and makes off with her. Pursued by the white family and shunned by Marbuck’s tribal council because of her wrong “skin colour”, their attraction proves fatal.

Driven insane, Marbuck takes Jedda with him in leaping to his death. The passion that Marbuck and Jedda aroused in each other had the same effect on the audience, leaning forward in their seats.

Chauvel, the director knew how to tap into the great fascination white Australians have for the land and its ‘noble savage’. Many see black blood as having been flyblown when intermingled with that of whites, as more important than the corrupting effect of their dispossession. We were spellbound by the physical beauty of the couple. There were few dry eyes in the cinema the evening we saw it. I heard much snuffling and blowing of noses around me. We were awed by the sight of this rugged wilderness, this savage Garden of Eden, alive for the first time in all its glorious colours. Later my father showed me the bluff near the Blue Mountains in NSW where the stirring finale had to be refilmed.

This film had all the right ingredients for a classic. Like ‘Apache’ it delivered its message in a popular action packed adventure formula. Marbuck could keep pace with Massai on the land, wrestling crocodiles, using fire to throw off his pursuers, using water to cover his tracks and being expert with both spear and rifle. Like “Apache”, it showed indigenous people in a more humane light, both providing a strong sounding board for me to discuss racial issues. It was highly critical of the then-prevailing policy of assimilation. It boldly rejects the notion that indigenous Australians should conform to the expectations of European Australians.

At the deeply affecting end of ‘Jedda’ no one in the cinema was moving. No one was talking. For several minutes the whole audience sat in stunned pin-dropping silence save for scattered gasped sobs, blowing noses and softly catching their breath. Red cast down eyes and clutched hankies betrayed what even the the stoniest of viewers had been reduced to.

The story had raised the question of what it is to be Australian.

It also raised the question as what had happened at the local rock formation known at ‘Gin’s Leap’, a towering wall of stone left high above the plane by a volcano millennia ago.

The name is said by some to derive from an Kamilaroi woman who leapt to her death. The widely accepted origins of the current name follow the tragic death of a pair of ill fated young aboriginal lovers, another modern day Romeo and Juliet. The young girl, promised to an elder of her tribe, the Kamilaroi, scarpered with a young aboriginal man from another tribe. Hotly pursued by tribesmen and the unwanted suitor, the lovers jumped to their deaths from somewhere along the top of the cliff face.

But did they really? It’s hard to say. Was this nothing more than a powerful illusion created by certain ‘gubbos’- whites- who had made it a tragic black spot.

You see, Rose had another version of the tale: ‘We don’t call the rock that name. It’s not nice. We don’t like being called ‘gins’ or ‘lubras’. It’s not respectful. Our people know the rock as “Cooloobindi”. A bunch of local farmers who saw our mob as a problem rounded up our women and they marched them to the top. They gave them a choice- to jump or to be shot. Black blood runs all over and that river it runs deep, no matter what the sign reads underneath Gin’s Leap.’

I’m not claiming to bear witness and I know people are sensitive to their history.

But if asked to pick a story I know which one I’d believe.

Our Neck of the Woods

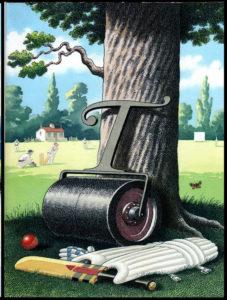

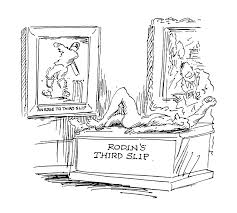

The power of the still image came to me in the illustrations and photos of our library books, but quantitatively in magazines and comic books. The proximity of words and images accelerated my reading ability greatly. That’s why I particularly loved cartoons.

Whenever I saw the images in books, I longed to have my own copy. Not alone, I had that envy of those who had the luck of the draw.

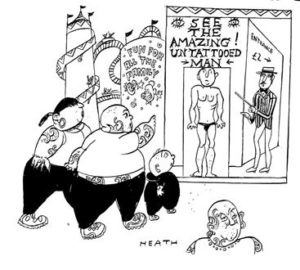

I accumulated a humongous repository of comics. Starting with a few, I swapped small ones for bigger ones and bigger ones for more smaller ones until shazam! I had a huge stock to marvel at. Popular items included Dick Tracy with his futuristic wrist phone that now seems so commonplace, and the nose thumbing Mad Magazine with its keen joy in exposing the fakery behind the images the ever more powerful mass media were pumping into our lives. The publication aimed a peashooter at corporate hype.

It’s mascot and cover boy was scrawny Alfred E Neuman. His distinct face featured his parted red hair, gap-tooth smile and freckles. It was an impish face that didn’t have a care in the world, except mischief.

Mad was magical, objective proof to kids that we weren’t alone, that there were people who knew that there was something off beam, phony and funny about a world of bomb shelters, brinkmanship and toothpaste smiles. MAD’s contrarian identity was clear from its debut, with its parodies of pop culture and a comic that skewered a new habit of suburbanites: gathering with friends to watch television while not speaking to one another.

The magazine gradually instilled in me a habit of mind, a way of thinking about a world rife with false fronts, small print, deceptive ads, booby traps, treacherous language, double standards, half truths, subliminal pitches and product placements; it tried to warn me that I could be merely the target of people who claimed to be my friend; it prompted me to be alert to to mistrusting authority, to read between the lines, to take nothing at face value, to see patterns in the often shoddy construction of movies and TV shows, to cut through the schmalz.

One of my finds was a classic copy of ‘Flash Gordon’, the space cowboy series which featured the evil emperor, Ming the Merciless. This was the cognomen given to Menzies (who pronounced his own name ‘Mingzies’) when he tried to deport an anti-fascist, anti-war immigrant to Europe before the war, my dad informed me.

Among my favourite reads was the popular comic strip Li’l Abner set in the fictional backwoods community at Dogpatch, U.S.A. This hillbilly world became familiar caricatures of American life. Sunday mornings would see me dashing along Conadilly Street to the newsagent to make sure I didn’t miss out on the newspaper with its comic supplement. Cars swerved to miss me as I sprinted across the roads, pedestrians avoided bumping into me as I walked back slowly along the street poring over the latest instalment.

The characters featured in this syndicated strip- Li’l Abner, his gal Daisy Mae, Mammy Yokum and others- satirized famous persons and customs.

In particular Daisy Mae’s voluptuous charms tickled my fancy. Much of it was visible thanks to her famous polka-dot peasant blouse and cropped skirt. Hubba hubba.

This strip created by the cartoonist Al Caplin, who abbreviated his name to Al Capp, included Charles Chaplin amongst its admirers.

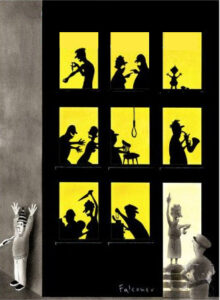

Appearing intermittently as a strip-within-a-strip was ‘Fearless Fosdick”, a spoof of Dick Tracy, set in an unnamed American metropolis lousy with crime, where the sun refuses to shine, where you shouldn’t make a sudden move. Where anything can happen and it usually does. Where you can have both your heart broken and your head broken at the same time.

Its urban setting filled with tough guys, burnt-out buildings everywhere, narrow alleys, rubble spilling out over the sidewalks, cheap bars, greasy spoon diners, people living on top of each other, their expressions reflecting the destitution of their surroundings.

So tough it was said you could walk six blocks without leaving the scene of the crime.

So tough you couldn’t avoid trouble. It came looking for you.

So tough the standard reply to the school teacher asking children, ‘What comes after a sentence?’ was ‘An appeal’.

So tough it was said even the muggers walked around in pairs.

So tough when asked how far it was to the subway a policeman replied, “I don’t know, no one has ever made it.

So tough even the police even the police had an unlisted number.

So tough the high school newspaper had an obituary section.

So tough you could receive a deliberate hit and run on the pavement from a pedestrian.

So tough when you went to buy silk stockings, the shop assistant wanted to know your head size.

So tough anytime you put your hand in some wet cement you felt another hand.

So tough when a medico bought a therapeutic water bed, he found a body at the bottom.

So tough every time you shut the window you hurt somebody’s fingers.

So tough the kids take hubcaps-from moving cars.

So tough in a good building, you got a doorman. He didn’t say ‘Good evening’, he said, ‘Good Luck.’

So tough In a bad building, you just got a man in a door.

So tough at Easter time the children had little porcupines instead of bunnies.

So tough if everyone was seen to be smiling at once, it must have been Halloween.

So tough giving the wrong look can land you in hospital.

So tough paranoid people moved there for health reasons. It’s the only place where their fears were justified.

So tough if you needed to exit off the motorway for fuel there you’d say, ‘Damn it, I don’t need gasoline that badly.’’

So tough if you stopped at a motorway siding you’d be content to see the city through binoculars.

This all stood in stark contrast to Li’l Abner’s rural Dogpatch. In combatting crime Fosdick was himself responsible for astronomical collateral damage,

Making for twice as much reading fun,Li’l Abner bookended the offbeat Fosdick sequences as a narrative framing device. Abner himself serves as a rustic Greek chorus—to introduce, comment upon and sum up the Fosdick stories. Typically, a spun up Abner would race frantically to the mailbox or to the train delivering the morning newspapers, to get a glimpse of the latest cliffhanger episode. Every so often I would walk back from the newsagent reading about Lil Abner walking away with his latest copy, reading about Fearless Fosdick. I got two for the price of one.

Subsequent instalments of L’il Abner would reinforce his obsessive immersion in the unfolding Fosdick continuity while at the same time recapping the story-within-a-story. Oblivious to the surrounding ‘real’ world Abe would walk off a cliff or into the path of an oncoming train, or inadvertently ignore one of Daisy Mae’s perilous predicaments. Occasionally the gullible, bumbling and impossibly dense Fosdick’s adventures would directly affect what came down the pike to Abner, and the two storylines would artfully converge. The story-within-a-story often ironically paralleled and or parodied the story itself. Also, by having the comically obtuse Abner “explain” the strip to Daisy Mae, Capp would use Fearless Fosdick to self-reflexively comment upon his own strip, his readers, and the nature of comic strips and “fandom” in general, resulting in an absurd but overall structurally complex and layered satire.

I can now, after a fashion, walk along my risky city floor reading about me walking along the risky country streets of Gunnedah reading about L’il Abner walking along the risky country streets of Dogpatch reading about Fearless Fosdick walking along the risky streets of the city. A story-within-a-story-within a story. It remains for some literary critic to write about my writing to extend the layers.

Sparing no-one his merciless needle, Al targeted all kinds of mossbacks, radicals and liberals. Some sharply satirical episodes of Li’l Abner were censored in early strips.

While the details remain sketchy, his irreverent art stayed with me as I got older. With adult readers far outnumbering juveniles, Li’l Abner forever cleared away the concept that humour strips were solely the domain of adolescents and children. Li’l Abner provided a whole new template for contemporary satire and personal expression in comics, paving the way for MAD.

I would commend Al for the wealth of characters he created. I pointed out to him that many country cousins of his rustic folk lived in our part of the bush. Al thanked me for having taken the time to write to him so kindly.

Wishing me the best, he threw in a drawing of Li’l Abner and Daisy Mae in full stride on one of their humorous adventures.

The Busy Bookworm.

“Read well and you will write well”

Sir Max Mallowan.

An archaeologist is the best husband a woman can have; the older she gets, the more interested he is in her.

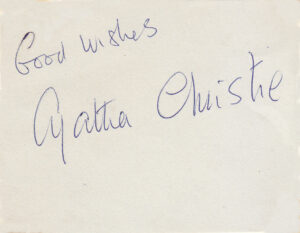

Agatha Christie on Sir Max Mallowan.

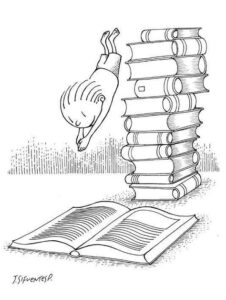

With an eye to learning and edification and with strong jaws I wolfed down books, my mother’s milk, from the local library, starting with the Enid Blyton children’s books when I was little. Gradually I began diving into boys stories of wartime heroes and space adventures.

By the time I entered secondary school I was one of the innumerable readers of the second most published author in the English; by the time I left I was tackling the leader of the pack.

When reading Shakespeare’s works, a turnoff to many inching through his works at a velocity of ten lines an hour, it broke on me that along with owning books, reading was one of the greatest gifts we have. It takes us beyond ourselves.

Some of my mates missed out sadly on both counts. They couldn’t read well.

They mixed up the stories.

One thought Hamlet was a baby piglet.

They never even knew we had a local library. It was kept quiet.

One day Jack Locock staggered into this municipal library. He rolled up to the counter and looked at the librarian Ms. Beth Rixon dead in the eyes and screamed ““Lady, I’ll have a bottle of claret an a packet of fags.’

Ms. Rixon shushed him and sternly said in a whisper, “Sir! This is a library!”

Jack immediately apologized and whispered slurringly,“So sorry, Lady, I’ll have a bottle of claret an a packet of fags.’

I encouraged one of my mates to find out about this vital resource. He rang up finally and asked Ms. Rixon: ‘Is that the local library?’

She said: ‘It depends where you’re calling from.’

When he eventually fronted up to her desk, he said, ‘I’d like to join.’

She said, ‘You have to prove you’re a resident of this area.’

So he quoted aloud the words of the local poet, ‘I love a sunburnt country, her pitiless blue sky,’ all the while baring his chest all red, blistered and raw.

She issued him with a card without further ado.

‘Now what would you like to read ?’she asked him, ‘and why?’

‘I’ve got some penfriends overseas. I’d like to be able to write good letters about what’s going on here.’

‘Why don’t you read ‘Jane Austen’s Letters’. She writes about everyday life, about things around her in England: the weather, health, clothes, social engagements including gossip.’

‘I could write letters about our local people and what they get up to. But would she read any of mine ?’

She asked him, ‘Would you like a book mark?’

‘Ms Rixon you just issued me with a library membership card. You should remember my name is Barry.’

Barry it is, then. Now Bazza, a bookmark will help you keep track of your progress in a book and allow you to easily return to where your previous reading session ended. It will keep you from dog earing the pages and preserve the book longer.

The Queen of Crime.

My mother was an avid reader of Agatha Christies mystery novels. I chose her books while I got my own and would plough through them all, exhausting the supply. I kept the town librarian, Beth Rixon on her toes stamping them with their due date.

‘Outside of a dog,’ she liked to say, ‘ a book is man’s best friend.’

‘Inside of a dog,’ I hastened to point out, ‘it’s too dark to read.’

I was a great one for borrowing books in the morning and returning them in the evening which flummoxed Mrs. Rixon. ’This is against the rules, Allan,’ she pointed out to me, turning a blind eye to this ludicrous restriction.

My familiarity with the ideas in these books and the experience of their author made me percipient of the thinking of my mother for whom they were a staple. I told Ms. Christie I appreciated her craftsmanship, spinning delicate webs of deception and mistruths in an effort to dissemble the real deal behind the façade. I told her that my mother and I had fun following the cleverly plotted and ingenious solutions that would never fail to surprise us. ‘Who knows?’ I asked myself, ‘maybe one day I too will write such mysteries’.

Indeed I would write a short one and it is part of this saga. Titled ‘A Case of Mistaken Identity’, the main character is my mother herself. The mystery is that surrounding her fate and the circumstances leading up to it.. Reading further will supply you with the clues needful for solving it.

I asked Ms. Christie to give my regards to her husband, the eminent archaeologist Six Max Mallowan whose digs she had accompanied him on. These provided background for some of her novels. Both stimulated my interest in lost civilizations and those who seek to discover them. Ms. Christie expressed her good wishes to me.

Her classic crime fiction is considered to be a leading example of the cozy or cosy style, a title which says a lot. While the subject is more often than not murder, it invariably takes place in a context that would be considered familiar, non threatening and not likely to bring significant unpleasantness to readers or to the other characters in the story. It starts with perfect order in which everyone fits securely into his or her place until a slight case of murder disrupts that order and reveals unexpected connections between the characters.

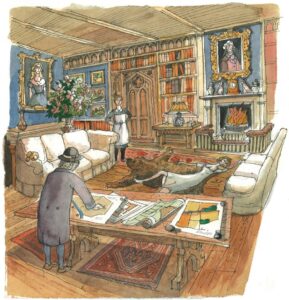

It is usually focused on members of a closed group, often in a European train or a village country house. In ‘Murder in the Library’, the members are at Gossington Hall.

The members generally become suspects in a generally bloodless and neat, clean murder. The case is cracked wide open by an amateurish but astute detective or shrewd spinsterly sticky beak doggedly sniffing out clues-footprints, fingerprints on teacups, secret doors and the like. The characters often reflect refined personal habit – Oxford dons, threadbare aristocrats supported by down in the mouth butlers, grooms, footmen, servers and gruff ruddy constables from the sleepy hollow. As with most good detective fiction, the puzzle seems impossible to solve until the last chapter when everything’s made transparently clear. The happy endings are usually preceded by confrontation induced confessions and erudite unravelling with a minimal acknowledgement of the social or factual aspects of the crime. Much of the deduction and logic used is to explain who is behind the corpse rather than the mind bending psychological factors that compelled the killer thus.

Murder investigations were much simpler back before the advent of DNA analysis. Our gruff village bobby might report to Miss Marple like this, ‘We’ve found a pool of the killer’s blood in the garage.’ And she would be like, ‘Oh how horrible. Mop it up. Now then, back to my hunch. I’ll keep looking for clues. I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We’ll draw chalk around the body is. That way we’ll know where it was.’

I came up with an alternative to the standard mystery formula: ‘The Butler Didn’t Do It.’ After the lord of the manor is found bludgeoned to death with a silver platter, the one armed chief manservant is quickly ruled out as a suspect. Upon observation of his working motions, Ms. Marple determined Jeeves could take it, but he couldn’t dish it out.

The Bleeding Heart

If you want to find an earlier parallel to the modern contemporary murder mystery, the closest similarity is the four Gospels, especially the first three, the synoptic Gospels. People are intrigued about the sudden termination of life because it says something about what life is about. Agatha’s stories are about the death of an innocent person. The Gospels are about the death of an innocent man and what it means. These kinds of narrative speak to us about our mortality.

The mystery that engrossed my mind the most was that surrounding the ritual killing of Jesus as interpreted by the Roman Catholic Church. While other children pondered the mystery of a giant bunny rabbit delivering chocolate eggs in the middle of the night, my beatific meditation was on the suffering and insults Jesus endured, shaped by the powerful visual narrative set out in the stations of the cross. These graphic scenes following his footsteps, stretched around the church, guiding my spiritual pilgrimage of prayer. I resolved to learn to speak in divers tongues.

My parents were both Catholics and the Church played a central role in my formative years.

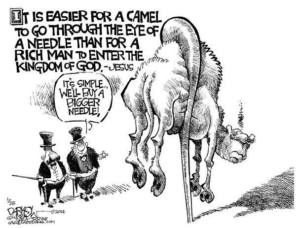

As a tyke, lining up at the altar rails, I was very moved by the image of the sacred heart of Jesus – a flaming bleeding heart encircled by a crown of thorns. A simple, credulous woman, my mother was ready to lap up any homilies dished out by the prelates. My father’s Catholicism was tribal, more secular, rooted in good works rather than dogma or pomp and circumstance. He didn’t flagellate himself or prostrate himself at the altar. Tempering his spiritual belief with a healthy dose of scepticism, he resembled so many Catholic men returned home after World War II. It was the war that sent away a generation of rich men and poor men and sent them back just men. Men that bled, men who shattered into a thousand pieces under fire, men who loved and felt fear and wanted better. While maintaining in varying degrees their ties with this almighty body with its allusion to saints, its penchant for sacrifice and its medieval views of the human condition, these Catholics in name had misgivings about the church’s restrictive social and sexual moves. They were deist in a airy fairy way, faintly Catholic in their outlook and ideas, not too much so.

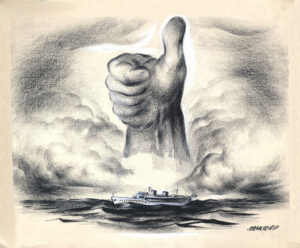

‘I don’t believe in miracles, Al.’ he once told me. They’ve only been said to occur in places where people were superstitious. But I did observe something once that resembled one. Flying back home at the end of the War we passed a troopship bringing back troops. Behind it was a little cloud formation resembling a hand coming out of the sea.

It reminded me of a Bible story I was told by the Brothers at school about such a vision.

Of course what I saw was my imagination at work. There is a human tendency to seek patterns in random information. Such sights are simply the result of coincidental patterns. The human mind chooses to interpret them in particular ways. I interpreted this little cloud as a sign of hope for a better future for the world. That’s because I wanted to see it that way. It was a more optimistic one than the mushroom shaped cloud over Nagasaki we’d just been shown.’

’

’

‘From what I hear, Dad, It will be a miracle if we don’t see bombs like this exploded again in future.’

I once asked him what happens after we die. He told me we get buried under a pile of dirt and worms eat our bodies. He could have reinforced what the Church led me to believe at the time – that if I made one false move I would fritter and fry eternally, stretched out on red hot gridirons in the nethermost fiery pit, great crimson flames of hell fire licking around me – but he didn’t want to upset me.

I wore my ‘heart’ not on my sleeve but under my shirt. Strung around my neck was my scapular, a religious emblem with a cloth badge illustrating the agony of Jesus. This symbolized Christ’s suffering and love for humanity.

I had to explain such customs to my friend Andy Dall who understood- but not totally.

During my penitential preparation for one Easter, he told me, ‘I’m not Catholic, but I’ve given up picking my belly button for lint.

In the Eyes of God.

Whilst a preteen parishioner, early at the rails, I always swung a ringside seat.

As an altar boy I was quite zealous in my service. I was given that old time religion. All day long I’d biddy-biddy-bum. Down on my knees, sealed by the Holy Spirit, I’d fiddle with my rosaries, bow my head with great respect, and genuflect, reflect, expect. I’d get in line in the long processional, step into that small confessional, find out if my sin was original. Kyrie eleison, I’d play it safer, bow down more to receive the wafer. Two, four, six, eight, it was time to transubstantiate.

Reading through the New Testament Gospels, I realised how often fish are talked about. I concluded the Jesus fish is a symbol of hope.

I always felt sorry for Jesus because no matter what he did he could never live up to his father.

In an aura of incense, stained glass and theatre, a culture of symbolism and imagery, I was right up front in all the action, serving devoutly both in the local church and in the chapel of the Sisters of Mercy. Assisting the men of the cloth discharge their ecclesiastical office with bells and smells gave me first hand knowledge of these celibate shavelings and the almighty institution they served.

While serving one cold early morning mass, I slipped and dropped the wine cruet. The sound of the bulb-shaped container bouncing across the hard marble surface echoed off the high walls and arched ceilings. Expecting a stern tongue lashing, I braced for punishment. But Monsignor Leahy the gruff, stern local priest was thoughtful instead. One mass in the vestry after taking off his chasuble, he told me, ‘Allan, Don’t be concerned. Such mishaps can happen to the best of us. The same thing happened to Bishop Fulton Sheen when he was an altar boy. He served in that capacity as well as working in his father’s store. Just like you. Do you want to become a shopkeeper like your father when you finish school?’

‘Dad would like me to go to university.’

“Tell your father that I said when you get big you might go to St. Patrick’s Seminary at Manly and someday you will be just as I am.’

That meant someone shrewd, quick thinking and terse. The story went that he received the following phone call from the Australian taxation department. It regarded how much one rendered to Caesar and how much to God.

‘Hello, is this Monsignor Leahy?’

‘It is.’

‘This is Robert Pritchard from the Commonwealth Taxation Office. Would you help us in an inquiry of ours?’

‘I would.”

‘Do you know a James Kelly?’

‘I do.”

‘Is he a member of your congregation?’

‘He is.’

“Did he donate 10,000 pounds to your church?”

‘He will. By the grace of God, he will.’

In the chapel attached to the convent, I assisted a string of priests who must have come out of the ark, too feeble to say the mass impressively in the parish church. Their idea of a good sermon was to have a good beginning and a good ending, then having the two as close together as possible.

One of these, lean, goggle-eyed and cadaverous, said to me ‘We must ritualise both the quick and the dead. Which ceremony do you like best?’

“Weddings”, I replied straight off, savouring the thought of iced cake and scads of other goodies, on top of the festive atmosphere of the occasion. They were especially enjoyable after the self denial of Lent for which one year I gave up abstinence. I managed to resist everything-except temptation.

I learned that ‘ best’ man was a misnomer as at first it was him I had expected to win the woman’s hand.

‘What about you Father? I asked,‘Which one does the Lord make you truly more grateful?’ My gut feeling was that his was the same as mine more than the lofty one he had come up with.

‘I prefer funerals to weddings,’ croaked the ancient cleric.

‘Why so, Father?’

‘It’s easier to get enthusiastic about a ceremony in which one eventually has an outside chance being the centre of attention.’

‘There’s more goodies here than at the Last Supper,’ I said at one reception. ‘For what we are about to receive, may the Lord make us truly grateful.‘

I often wondered why none of the disciples sat on the other side of the table. I reckoned that originally there were people sitting on the other side but those were the people going, “You know, there’s a strong draft from Mount Zion hitting me right on the back on the neck.’

I often wondered if there were any unrecorded miracles that took place there.

I observed the appropriate emotions accompanying each ceremony.

I learned why it is that we rejoice at a nuptial and cry at a funeral. It is because we are not the person involved.

I thought about the emotions funeral directors faced by the constant passing of human beings. They had to struggle with the constant theme of death, grief and loss. I could sense their irritability and impatience, particularly when they had to kill time waiting around for the requiem mass to finish.

Monsignor Leahy radiated joy after each wedding.

At the funeral of one of the local wealthy graziers, a man was crying inconsolably as if his heart was shattered. ‘Now cracks a noble heart,’ he declared while sobbing, ‘ Goodnight, sweet prince, and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.’

‘I see how difficult this is for you,’ said Monsignor Leahy. ‘Were you closely related to the deceased?’

‘No, he said, choking back a sob.‘ I wasn’t related at all!’

‘But then why do you weep?’

‘That’s why!’

I was always relieved when the priest was delivering the eulogy and I realized I was listening to it.

The ancient cleric had to comfort one of his parishioners who had just lost her husband, a lapsed Catholic.

‘God bless you, Father,’ she said, ‘I’ve just come from the church where I lit a candle.’

‘That’s the spirit,’ said the cleric, ‘he’ll need all the help he can get.’

The cleric wasn’t too involved when he was commending the soul of the deceased husband to the Lord. It was an appropriately funereal day, the wind was blowing hard, rain pelting the black crowd of umbrellas and everyone wanting to get it over with. I swear so help me while watching the coffin being lowered into the ground I could hear the priest saying, ‘In the name of the father and the sun and into the hole he goes.’

‘Now your dear husband can get that final rest he always said he needed,’ he said to the widow to console her after the service.’

‘He needed a new car. He needed a heater in our bedroom,’ she replied, ‘A burial plot is the last thing he needed.’

We were in the car once with a load of slow moving cars in front of us. The cleric cried, ‘How is it possible people are driving so slowly. Even if you were out for a Sunday drive, you’d be faster than this. Driving like that requires honest to god mental effort. They must be doing it on purpose just to get on our goat.’ He got very ropeable and started shouting.

‘Hush Father,’ I said, ‘you’re ruining the funeral procession.’

After the sad ceremony I asked Colin Sills , my fellow altar boy, “When you’re in your coffin, and your friends and church members are mourning over you, what would you like them to say?”

Colin said, “I would like them to say, ‘Colin was some kind of wonderful Rugby League player, a kind person who made a huge difference in people’s lives.”

‘What about you, Allan? What would you like them to say?’

Colin and I we were always competing at sports carnivals and athletic competitions.

Sadly he would pass away in his sixties. This would prompt me to say that if life is a race, then he has beaten me to the finishing line. But if it is a boxing match. then I am the last one standing.

At one wedding we officiated at, a bubbly old hen poked a nubile neighbour and said, yanking her chain, ‘You’re next.’

She didn’t like it when the young woman returned the comment some time later. They were both attending the same funeral.

At one shotgun wedding, a case of wife or death, this priest disapproved of the groom drinking so heartily. ‘My wishes for a healthy family’, he went up and said to him.’ I hope there’s nothing in heredity.’

‘Marriage is a most sacred ceremony,’ he declared to me ponderously. Protestants can wriggle out of it without compunction. For them anything goes. Wishy-washy versions of what the Lord expects.

Those supermarket Protestants can choose from the shelf what’s convenient, what’s easy, what suits them, what’s within arm’s reach, and leave the rest. They call themselves believers yet embrace a disposable God. Consequently, too many are mispronounced man and wife. The Archbishop of Canterbury adds an escape clause for those wishing to remarry. He says it is their private responsibility, and if they seek marriage, it must be by a civil ceremony without trying to involve the Church in the act.

Monsignor Leahy told me you’ve read about Pearl Buck. He didn’t want to tell you but that fallen woman spells trouble for Christianity and the family. This sexually incontinent whore of Babylon is in cahoots with that cancerous sore, that Communist Robeson. She once told a large gathering of Presbyterians that missionaries do more harm than good. Can you believe her own father was a missionary himself? So much for the absurd idea that priests should be able to marry. What’s the world coming to?’

‘God only knows, Father ‘,I replied, nonplussed, thinking of things that weren’t necessarily so. Mind-benders as the Creation. In the beginning we were told there was nothing. God said, ‘Let there be light!’ There was still nothing much, I gathered, but you could see it a whole lot better.

The world was made in seven days. Seven was the magic number so in accordance with the mystic rules of life we got seven seals, a lamb with seven horns and seven eyes, seven days of the week, a dance of the seven veils, seven deadly sins, seven seas and seven brides for seven brothers. We got Feeding the Multitude- thousands of people dining on seven loaves of bread and fish, requiring enormous skills in preparing tapas. I had fancied my own chapter of the seven seals: seven samurai eating tapas out of seven bowls to the sound of seven trumpets.

We almost got the Seven Commandments except for Moses holding out for a better bargain:

‘These are great, God. How much are they?’

‘They’re on the arm. Free. ’

‘I’ll take 10. That’s all I can carry due to my arthritis.’

‘We got the Virgin Birth-test tube babies were not yet possible, the Ascension- what some less reverent call ‘ Jesus moving back in with his parents, ’and Transubstantiation, changing bread and wine into a man’s body and blood without the need for any digestive tract. We got the Trinity-the three in one, the triple treat. We got the parting of the Red Sea.

‘People have all kinds of absurd ideas these days. Like the seventh son of the seventh son. They believe in the Abominable Snowman and the Loch Ness Monster. They believe that four-leaf clovers, horseshoes, copper bracelets, tooth fairies, wishing wells and rabbit foots will bring them good. They believe in fairies at the bottom of the garden. ’

‘People have all kinds of absurd ideas these days. Like the seventh son of the seventh son. They believe in the Abominable Snowman and the Loch Ness Monster. They believe that four-leaf clovers, horseshoes, copper bracelets, tooth fairies, wishing wells and rabbit foots will bring them good. They believe in fairies at the bottom of the garden. ’

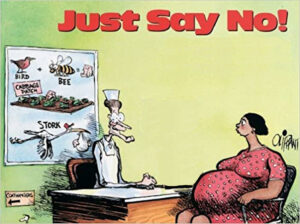

‘ As for Mrs Buck or whatever she calls herself nowadays she should know that God created women from the rib of Adam, that her ordained role is as homemaker and mother to her children.

Rumour has it she and her new husband might turn to a surrogate mother to bear their baby. The Church forbids this practice.’

‘It’s a good thing they didn’t have that rule when Jesus was born.’ I thought.

‘I’m told she wrote a book about a female sculptor who chooses a career over her husband. She should hang her head in shame. She has no respect for herself or the sanctity of marriage and has trampled on it, choosing to abjectly remarry the very day her divorce papers came through.’

‘In the eyes of the Church, two rites making a wrong.’

‘She must think husbands are like Kleenex tissues, soft and disposable. She never lets her sheets cool down before she brings someone else into the bed. I hear she even bought a drip-dry wedding dress. What does she think monogamy is- a type of wood?

‘Maybe,’ I thought to myself, ‘ for many it sounds too much like monotony. If ‘I am’ is reportedly the shortest sentence in the English language, could it be for that demographic ‘I do’ is the longest sentence?

‘How can she ever live this down? It’s contrary to the Scriptures.. For us in the true tabernacle, we cross our hearts and hope to die. Marriage is an iron-clad contract you can’t just break at will. It was ordained for the procreation of children to be brought up in the fear and nurture of the Lord, and to the praise of His holy name. Marriage is made in heaven.’

‘So are thunder and lightning,’ I thought.

The Church cannot make exceptions in its public solemnization of marriage without compromising its witness. Woe betide those who sin by such erotic vagrancy, yearning to satisfy their carnal iusts and appetite like brute beasts that have no understanding,” he whined on, bending my ear, thus implicating one of my esteemed aunts who he would have considered had transgressed in this way. “Those who knowingly violate this law of the Church are thereby ineligible to receive the sacraments including the Holy Communion we share,” he pontificated. They are committing mortal sin. If they die with this on their soul they will go straight to hell, cast out from God’s love and denied the sight of him for all eternity.’

‘Eternity’s a terrible thought… I mean, where’s it all going to end?’

‘That is decided on Judgement Day. If a person is found to believe in Christ they will go to everlasting bliss with those who reject Christ going to everlasting condemnation, never to see their heavenly father. ’You wouldn’t that, would you’.

“Not by the hair on my chinny-chin-chin. What can one do to avoid such a penalty, Father?” I asked. “The couple must seek a dispensation through the Sacred Rota, the church’s supreme court. Only it can decide on such matters. Only it can issue an annulment. If they walk away from this ruling they risk being excommunicated”, he concluded his jeremiad with.

Sweet Jesus, the idea of my aunt being subjected to such mumbo-jumbo led me to hold such an archaic procedure in derision. How in the name of reason can it be sinful for a man or woman to live with the one they love? People should be free to marry whoever they want and call it quits whenever it’s on the rocks. They should be honest and come clean. Instead of standing in front of an altar saying ‘Til death do us part,’ they should just go, ‘I’ll give it a shot.’ How on God’s green earth can anyone else – especially someone who’s never been married – demand a relationship driven by messy incompatibility be maintained at all costs.

It was one thing for a man or woman to resist an aspiring partner’s advances. It was another to block their retreat.

The idea of a woman’s feelings about pregnancy was dependent on her marital status. The strict taboo against love outside marriage even extended to the medical profession.

One of the local Catholic medicos entered a consulting room where a young woman back from Sydney to reconcile with her family was sitting. ‘Good news, Mrs Smith!’ he said.

‘Miss Smith, ’she replied.

‘Bad news, Miss Smith,’ came his reply.

The advice his practice dished out to women in the family way was short and simple: If you want to stop this happening again—’

As for the annulments these struck me as being economical with the truth somewhat, as akin to the sale of indulgences, with similar effect. They allowed Catholics who had once gone and got married in good faith to claim that they hadn’t done so, to gainsay these marriages – despite their vows and often the existence of children – rather than admit their error without cutting the hem off truth’s garment, and make a clean break.

Curious to know how the Church was going to stop people leaving, ’I asked the priest, ‘How can the Church convince people to follow its rulings?’

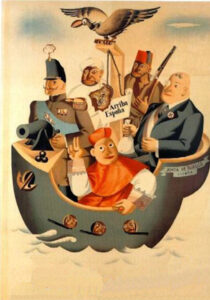

‘It’s simple. We need a government like that in Spain to set the lead and enforce our laws. One centred on the Church, ’ he declared, full of fire and brimstone.

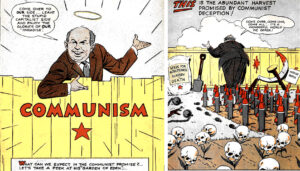

‘Not on Communist manifestos. We need to remove these repellent Reds from God’s sight.’

‘They didn’t destroy all the churches in Spain,’ I told him. I’ve seen pictures of lots of them in books.’

‘They rebuilt many. I say if you’re looking for nice new churches, go to Spain. If you’re looking for sin, go to hell!’

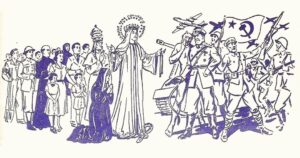

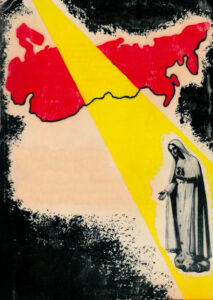

The priests and nuns had a very dim view of the Communists. I came across a pamphlet in the presbytery produced by the Catholic Catechetical Guild Educational Society. It was part of a “Red Scare” in the U.S. that raised fears about the horrors of a communist takeover.

In primary school The Sisters of Mercy gave us comic books depicting them as sinister figures skulking in the shadows and as mass murderering slicksters.

.‘We have to have a firm hold on what people can read, see and do. Women used to respect themselves. Now brazen hussies flirt, flaunt their ankles and bosoms shamelessly in the street. They smoke, wear immodest pants, go rutting and get knocked up. The Church has a duty to protect the vulnerable from this fascination with the materialist. This so called rock and roll that inflames the passions with its pelvic thrusts, leg sliding and debased body grappling. So many occasions of sin multiplied beyond our imagination. We live in this world, not of it. We need Catholic rules, not Rafferty’s rules, to clean up the cesspit people are exposed to. ‘It’s God’s will.’

‘And you’re doing your best to back up your vindictive version of him,’ I thought.

‘Like Franco we have banned the outrageous film ‘Viridiana’. The Holy See supports us It has denounced it as ‘blasphemous.’

‘So there’s a superior being,’ I thought, ‘someone who can make the mountains, the oceans and the skies, but who still gets upset about something someone said. He’s an all-powerful being, would he have such self-esteem issues?’

‘If God doesn’t destroy the studio responsible, he owes Sodom and Gomorrah an apology,’ the cleric rambled on.

‘The film’s distributors should pay for an exorcist,’ I suggested. ‘That way they won’t get repossessed.’

It’s got a “Last Supper” scene featuring crude, ruthless stumblebums and gorging, guzzling poofs in place of Jesus and the apostles. What sacrilege!’

This didn’t fit in with a biblical admonition I had read: “But when you give a banquet, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed.” (Luke 14:13. It didn’t fit in with the view of St. Lawrence that such persons were the treasures of the Church. It didn’t fit in with the story of the Good Samaritan which urges us to tend to our neighbour when he or she needs help.

‘Father,’ I said to the priest, ‘We should only look down on the wretched of the earth when we reach down to help them up.’

Our Lord and Saviour always wore sandals and he never married. And he had twelve disciples and I don`t think any of them ever married. And the apostle Paul, he was a Iifelong bachelor. And you never heard anybody in the New Testament say that they were a bunch of ‘poofs’.

I wanted to take the priest on over what I felt was a departure from christian values, but being young and inexperienced I bit my tongue.

I settled for asking him as he ponced about, telling people what to think, what he thought of the changes being brought about by Vatican 11.