“Therefore I say that it is a narrow policy to suppose that this country or that is to be marked out as the eternal ally or the perpetual enemy of England. We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”

Henry John Temple, twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century.

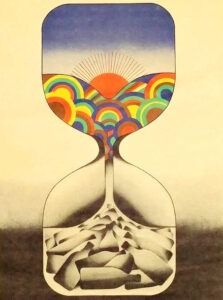

The first forty years of life give us the text; the next thirty supply the commentary on it.

Arthur Schopenhauer

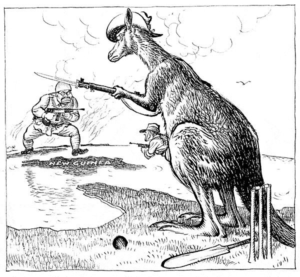

I was fortunate to grow up in the period after the Japanese military threat towards Australia had been halted. Banzai!

Nine months after one small after explosion, I was one of millions come to replace those who had just died.

During my gestational period I felt like a man trapped inside a woman’s body, struggling to get out. I didn’t know where she ended and I began. After my birth , as I grew, I would increasingly feel like a man struggling to get back .

I quickly learned of life’s complications.

When I was born, I had to meet a special condition. Even then there was a string attached.

After being rid of the stain of my original sin I was so surprised about all this I didn’t talk for a year and a half.

Not that I noticed. It all slipped by me somehow. I guess I wasn’t paying attention.

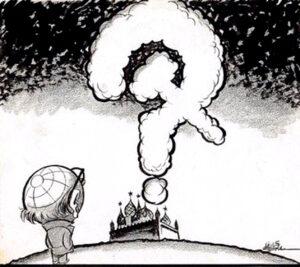

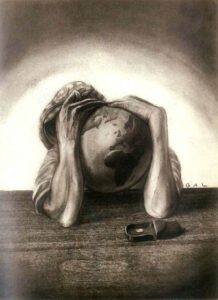

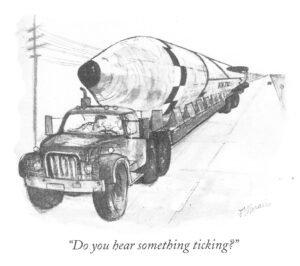

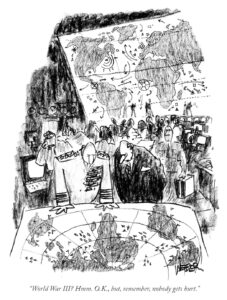

This was a brave new world I had entered, a new, hopeful yet uncertain period in history- the beginning of the Nuclear Age.

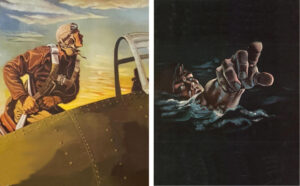

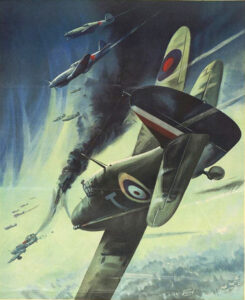

All the adults around me had had direct experience of the war. Dad had served on Catalinas, twin-engine flying boats used extensively for patrol and rescue duties. Airmen downed by enemy fire or mechanical problems awaited anxiously and hopefully being saved by them .

They flew missions in the band of islands and peninsulas to our north. Now forming Malaysia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, Now forming Malaysia, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, this region came to be Canberra’s primary strategic concern after the war. The presence of my father (his head framed by the two biggest boys) and his comrades was welcomed by the locals in Borneo.

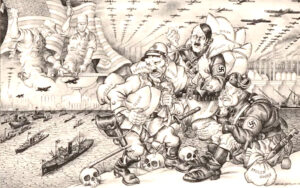

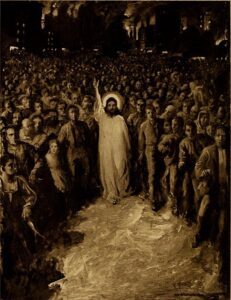

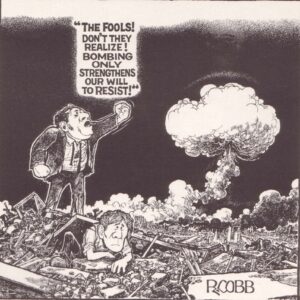

He would tell me the story of the war and I was deeply marked by it. I felt particular compassion for people who had had bombs rained upon them. I would become increasingly interested in the victims of war, the people running the other way.

Dad illustrated his account with his own photographs and those taken by Cecil Beaton to widen the scope. Beaton was officially employed by the British Ministry of information. He recorded the war at home and abroad, preserving sombre moments that changed the face of the earth forever – the bomb damage on the streets of London,

He showed the Wellington bomber crew who hit back at the Germans.

I was particularly moved by his unforgettable photograph of a three-year-old girl sitting in a hospital bed holding a teddy bear after being injured in a German bombing raid.

This deeply sympathetic photograph was as powerful a piece of visual propaganda as any made during those years. It was widely seen in the U.S., still refusing to join the conflict at the time. It commanded Americans to take a keener interest in a war that, at that stage, still felt very far away.

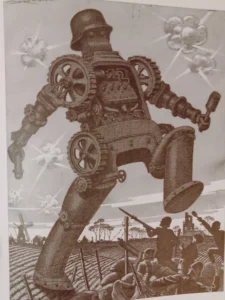

In like manner I was affected by the images of the Soviet forces battling the German invaders.

The key battles fought by the Red Army on Ukrainian soil destroyed the spinal cord of Hitler’s Wehrmacht and led to the Fall of Berlin.

Operation August Storm, the massive 1945 Soviet invasion of Manchuria, was Japan’s death blow, and brought an end to World War II.

Raised on this war , in which virtually everything I saw was heroic, I looked up to, was proud of and would aim to measure up to my father, W.B. Davis, number 61245, Australian Air Force, Roman Catholic as stated on his metal dog tag, my only lasting keepsake of him, along with a few photos.

Oh Mein Papa

Oh my papa, to me he was so wonderful

Oh my papa, to me he was so good.

Oh my papa, to me he was so wonderful, Deep in my heart I miss him so today.

It was a German song of all things ‘O Mein Papa’ that expressed my early feelings about him. I was much taken by the instrumental version of trumpeter Eddie Calvert. It always sets me off. Like my father with me, it reached number one.

He bore no ill will towards the Japanese and the Germans. While proud to display his badge of service he didn’t wear his heart on his sleeve. He didn’t particularly like marching in the annual Anzac Day parades and the attendant boozing and gambling. He was aware that most people longed for peace. He wrote as seeing himself having largely influenced my ideas. He was always respectful to my mother.

My earliest distinct recollections were happy ones whiled away basking in the fond embrace of my family, filled with a sense of protective wellbeing.

Tweedly tweedly tweedly dee. The essential advantages that life could bestow on me.

I was the apple of my father’s eyes. Mum thought the sun rose and set on me. From my very beginning, it was ‘darling Allan this, darling Allan that’ from her. My cup runneth over. From day one I received what would be a wealth of encouragement from others which continued throughout the passing years. These sentiments I would in turn pass on to others. Like many families being started up at the end of the war, ours had been put on hold. I was dimly aware of the lingering austerity and rationing.

As a baby boomer my childhood was played out against a most propitious period, the years of the long post war boom which historians have come to call capitalism’s golden age. Throughout the Western world high rates of economic growth coincided with low inflation and negligible unemployment, favourable conditions for political compromise and “consensus.” If you were white and well off, it seemed like Avalon. Fed by the spoils of victory, I was bred with the haste and dispatch and muscle flexing of a nation buoyed by its own success and good fortune.

Getting back on their feet, my father’s generation, returning home could hardly be called lost. The desperate shortage of virtually all goods and services triggered a situation where there were more jobs than people to fill them. As the post war austerity measures were fading they saw fit to establish a business in a country town in northern New South Wales.

After being demobbed, Dad had become an employee of Australia’s largest confectionery company based in Tamworth. Allen’s Sweets. How could I resist with such a name? Such sweet memories for me. Boiled sweets, bullseyes, all days suckers. Goody, goody gumdrops! Driving their bright red van around and distributing their products enabled him early in the peace to reccy the area and look out for the best prospects.

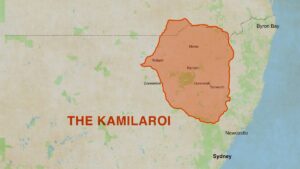

Tamworth lies inside Kamilaroi country, where the hills meet the plains, the red soil meets the black soil, the burr meets the spinifex and the rainforest meets the bush.

After giving it the once over, he decided upon Gunnedah, a prosperous town in the backblocks settled by squatters in the 1830s. They had followed in the tracks of the explorers, hewing a path with wagons and cattle,

putting down their loads. Claiming this rich soil and grazing land as their own, this common clay had to adapt farming techniques in an unfamiliar landscape.

They had lost every perch and rod of their own ancestral lands, their forebears having been forced off following the English enclosure acts. Initially unauthorised, they had the right of pasturage from the government on easy terms.

Stuffing all our belongings under a canvas stretched across our flat truck bed, westward we rolled to our new home.

Stone Broke.

On a visit to the Australian Museum in Sydney, I gazed in wonder, nose pressed against the glass cases, weaving the legends I had read in and around the groups of life sized figures with their woomeras, spears and boomerangs. My father entered a float in Gunnedah’s big yearly procession with exhibits of these artefacts on loan from the ‘Edgells’ food company.

‘What do you call boomerangs when they don’t return?’ I asked him.

As a nipper in Gunnedah I had a nanny, Rose Watley, from the Kamilaroi First Nations group.

Rose lived in a hut at the edge of the town. It was a step up from a humpy, but oh the location! location! location! Without electricity, running water or proper drainage, it was at the edge of the local rubbish tip where refuse was burned off.

‘How long does the burning go on?’ I asked her.

‘The garbage is always glowing, even at night, and you hear popping sounds. I think it’s batteries exploding.’

The dump was her shopping centre. It furnished her hut, made of timber, corrugated metal and old tarpaulins scavenged from the dump site. Surrounded by toxic smoke, this modern hunter gatherer picked over the garbage, careful not to step on rusty nails and broken glass, salvaging bottles, listening for the sound a prong makes when it finds a plastic container, searching the rot for glints of light-silver spoons, tin cans, pieces of machinery and whatever could be sold as scrap metal. These would all be recycled, an essential task.

Standing there watching cars and trucks arrive and leave, I tried not to breathe in the foul stench of everyday household waste as it gently rotted. Around noon in summer as the hottest part of the day approached, the fumes and the smell of the dump circulated. A constant black writhe of flies covered every moist surface, forcing you to speak with clenched teeth. The smell was so strong that it got into your throat. You could taste the smell. Your eyes watered.

‘Every morning I wake up,’ said Rose, stuffing lead pipe into a sack, ‘my throat is burning and my chest is tight. I have difficulty breathing. I just have to wait until it goes away.’

‘How do you put up with this,’ I asked her.

‘It’s awful, I know, but with time you get used to it.’

I could have. But only after I’d grown my third set of teeth. I had all the comforts of a decent home. Hers was the kind of poverty and destitution portrayed by Charles Dickens and Victor Hugo. The sight of my beloved nanny, one of the true working poor, fossicking through such waste was one that became burned indelibly into my young brain. I became colour blind.

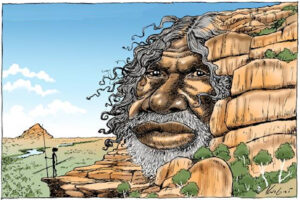

While her roots ran deep and straight, my scorched earth mother was not officially an Australian. The name of her tribe who lived in the area, the Kamilaroi (or Gamilaraay) means ‘having not’.

The name of the town derives from their word for ‘place of white stones’. I imagined the stones to mark the boundary between the Kamiloroi and Witchetty’s tribes.

Rose told me where the stones used to be. A sizeable outcrop of white stone where the public school stands.

‘My people used them as tools.’ said Rose. ‘For them, they were sacred. They put them in places where they were essential to survival.’

During construction the white stony outcrop was covered up – as were feelings for their loss. Her people hit rock bottom. They were so poor they had no dirt, They would not collect at the start. As they had come into the world, so they would go out. Every inch of the land that they could see, all that lay beneath it belonged to someone else.

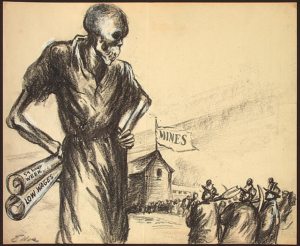

No one knew this better than the Kamilaroi miner outnumbered by his white comrades at Blackjack Colliery in 1917.

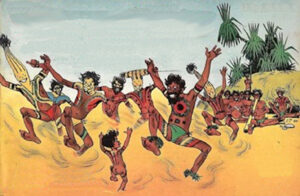

There were no vestiges of tribal life to beckon Rose. For most, her people largely sank without trace, except for local place names and tourist references. Strangers in their own country. A country with a black history, whitewashed when the wagons were corralled. The legends illustrated with paintings, acted out with dance and accompanied by music- and going back longer than anyone else’s were not being told. Sacred songs and performance of ritual had strengthened survival, playing a central role in their spirituality. One of the major purposes of traditional Aboriginal dancing was to tell stories, which were passed down through generations. These stories would be about the land, animals, dreamtime, and Aboriginal people. The stories and dances could also be used as an initiation process, or to celebrate a new stage of life. For example, ceremonial dancing and storytelling was a large part of coming to age celebrations for teenage boys and girls, initiating them into adulthood.

Rose’s mob had lived a nomadic existence around the Namoi River which rises on the western slopes of the Great Dividing Range before flowing westwards and downstream to Walgett.

They had lived like this since time immemorial, when all our ancestors were in the Stone Age. True children of nature, they lived in harsh harmony with the environment, not overly tampering with the natural balance, their ecological footprint modest.

They used fire to care for their Country , including burning or prevention of burning. This promoted the health of particular plants and animals.

It involved patch burning to create different fire intervals or be used specifically for fuel and hazard reduction purposes. Fire was used to gain better access to country, to clean up important pathways or to control invasive weeds.

They went from feast to famine, from flush to fallow, from stuffed to starved. Feeding voraciously during the all too rare rainy seasons, they built themselves up to survive the lean, skimpy years of drought.

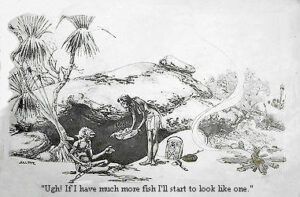

Their whole life style was based around the river. In the dry months of the year, Rose told me, they built a yard of boughs and brambles at a river spot. Then at flood time they would go out in their canoes and, spotting a shoal of fish, drive them as one would a herd of cattle into the yard where they would be an easy target for their spears.

They believed they were given the sacred land in trust. Their society had no school but children were educated by elders of the group. They developed their skills by taking part attentively in the group’s activities.

Aboriginals believe a person’s soul or spirit is believed to continue after their physical form has passed through death, After death their spirit returns to the Dreamtime from where it will return through birth as a human, an animal, a plant or a rock.

The 1830s was the beginning of the end for their traditional life, achieved through what Don Bradman called uncompromisingly ‘murder’ and ‘plunder’ of their tribal lands by his forebears and mine. They would lose access to common land as inexorably did the forebears of the white settlers with little to their name. Most would feel that they had been sold down the river. These have-nots would rub shoulders on the fringe of society. Where they had scattered chips of stone used for making tools, now there were just chips on their shoulders. They were all litterlouts according to the stoniest of hearts.

One of the most familiar faces on Australian television, Ray Martin, remembers in Gunnedah on a Saturday night at the pictures. ‘All the Aboriginal families were pushed down the front, usually to sit on the floor,’ he says. Their children could be discouraged from using the swimming pool.

Ray continues,‘ I was appalled as a ten or eleven year-old going down the swimming pool and seeing one of the lifeguards hosing down the aboriginal kids before they were allowed to go in the water. I wasn’t hosed down.’

He passed for white although he found out many years later his great, great grandmother was a Kamilaroi from outside Gunnedah.

My abhorrence at this degradation of one as worthy as Rose formed the basis of my lifelong identification with those living on the margin. It formed my serious concern for the fundamental values of human life.

Are You Being Served?

As a cheery chirpy lad, dry behind the ears, I took pride in the buckled belt holding up my pants. Eventually, my pants would have belt loops holding up the belt.

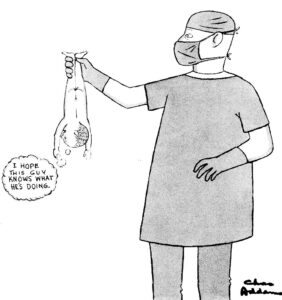

What would be going on here? Which of these two was the real hero?

Both feet on the ground, developing both social and resourceful sides of my forbearing character, I engaged in enterprises reflecting these as my stock-in-trade.

‘Waste not, want not, Al. Don’t let your eyes be bigger than your stomach.

It’s a sin to waste food. In Asia they’re as hungry as the wolf felt when he met Red Hiding Hood, so finish what you’ve got,’ Dad always told me at the table. Trundling around the town and environs with my billycart I scoured the scene for empty beer bottles. Fetching a penny each, recycled they would be filled with industrial fluids. With methylated spirits and turpentine these would often slosh down the same desperate glugging gullet as the original contents.

Another useful cargo was manure obligingly deposited on the roads by stockmens’ horses and in stables I cleared. Added to our strawberries a bushel and a peck – into the loam, naturellement– it made for big juicy fruit. Ever on my toes to the opportunity of combining pleasure with business, I stumbled upon a nice little earner, an offbeat financial sideline– selling the wool from dead sheep I came across.

However, this busy bee’s main job was working alongside my family. While shops closed at lunchtime on a Saturday and reopened on Monday morning, we operated without any personal boundaries. My parents’ store was open all hours. It was a general store, although customers could buy anything specific. I remember a local with a hearing problem come into the shop and ask, ‘May I have a bar of soap, please?”

‘Do you want it scented?’ I enquired.

‘No’, he replied. I’ll take it with me now’.’

In the old fashioned way, we dealt in groceries at first and later alcoholic liquor and all kinds of raw produce and fuel for the home and farm.

Our motto was “If you can’t find it at W.B. Davis’, you’re probably better off without it!”

My father got to know our customers’ individual needs.

‘Your finest Scotch, please.’ one asked him.

‘Yes, sir,’ Dad replied as he handed him a ten year old roll of tape.

I helped serving people, keeping stock and helping hold the fort until I left school. My orderly approach for storing both objects and ideas was established here: A place for everything and everything in its place. I made sure they stayed there ’til the right moment. What customers came in for was their business. With customers like ‘B.O. Plenty’ what they went out with was our business.

‘If you don’t want to pay for groceries, ‘I reminded B.O., ‘You’re going to get an awful lot of ‘No sir-ee’s.’

One day he came into our shop and asked for five shillings worth of methylated spirits.

‘Five shillings worth of methylated spirits?” I said, suspecting he might drink himself blind, ‘what is it you want it for?’

‘Two shillings’, replied B.O.’

‘I’m afraid I can’t help you out there.’

‘In that case thanks for nothing, If you happen to find yourself down by the river, drop in!’

Another day when he was presumably more on top of things he entered the store.

‘What can I do you for today, Jack?’ asked my father.

‘Ten gallons of red ned please.’ As well as bottles we a sold it in bulk straight from the cask. More bounce for the ounce.

‘Did you bring a container for this?’ asked Dad.

‘You’re speaking to it.’

‘Would you prefer an aged wine or one with with a short shelf life ?’

‘Wine improves with age. The older I get, the more I like it. Now can I get this on tick?’

‘B.O.,’ Dad answered, ‘You know the banks along Conadilly Street.’

‘I know where they are but I’ve got no account there to withdraw from.’

‘The thing is I’ve got a business arrangement with them.’

‘What’s that got to do with me?’

‘Well, B.O., the deal is they don’t sell grog, and I don’t lend money.’

As this retail trade became more self service based, turning our ledger from black to red, we still had to inform customers about the products they were buying. Some had difficulty understanding the contents and instructions. One customer fronted up and said: ‘I want to make a complaint – this vinegar’s got lumps in it.’

I corrected him: ‘Those are pickled onions.’

Another limped into the store to complain about the tin of soup he had bought: I haven’t been able to walk properly for days. The label said clearly, ‘Pierce lid and stand in boiling water.

Another customer asked ‘I’d like to buy some deodorant please.’

‘ Cream or ball?’

‘No. Underarm.’

Upon the introduction of the push up deodorant, one young male customer targeted a third area where he applied his. He asked me for some ‘bottom deodorant’. A little bemused, I explained to him that we didn’t sell anything called ‘bottom deodorant’, and never had. Unfazed, the guy assured me he has been buying the stuff on a regular basis, and would like some more.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said, ‘we don’t have any. Do you have the container it comes in?’

‘Yes,’ said the customer who lived close by. ‘I’ll go and get it.’

He returned with the tube and handed it to me. After inspecting it I looked at it and said ‘This is just a normal stick of underarm deodorant.’

He took the container back and read out loud from the container: ‘To apply, push up bottom.’

Another query: ‘This cereal box says it contains a free gift. Aren’t all gifts free?’

I got to know the area well as we delivered supplies to customers both in town and country. A small town where everyone knows everyone, -sometimes too well. Where everyone knows everyone’s business, their faults, what’s happening in their marriages and where the kids have gone wrong. It takes all sorts to make up a world. I got to meet lots of people from different backgrounds and got to understand the rituals and roles played out before me. I picked up on the differences between the classes, the perceptions, the privileges, the taboos.

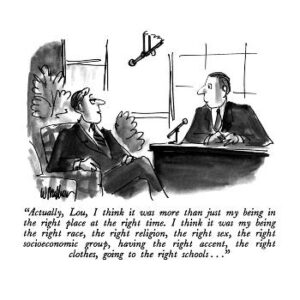

The distinction between the classes, cliques and castes seemed pretty clear to me – based on education, religion, accent, where they lived and how they worked.

These were groups of people with a common relationship to the means of production, with a common consciousness of identity and a common interest in opposition to those of other classes. Watching them go about their business, I observed their different lifestyles keenly. The owners of the stores, salespeople, doctors, dentists, nurses, builders and clerical staff. The butchers, the baker, the undertaker. Wealthy squatters on their large properties, the old money social set at the top of the pile, centred on the town, with their balls, picnic races and polo matches .

These were groups of people with a common relationship to the means of production, with a common consciousness of identity and a common interest in opposition to those of other classes. Watching them go about their business, I observed their different lifestyles keenly. The owners of the stores, salespeople, doctors, dentists, nurses, builders and clerical staff. The butchers, the baker, the undertaker. Wealthy squatters on their large properties, the old money social set at the top of the pile, centred on the town, with their balls, picnic races and polo matches .

The farmhands who worked for them and the shearers who were contracted to clip the wool.

We were often the only visitors some cow and wheat cockies or farmers on the land saw the livelong week. They greeted us with open arms, particularly in the summer. We could see them as we approached, waving their arms constantly. The great Australian salute to keep away the flies.

We went for weekend drives around the surrounding countryside. After we’d pass a few of those kangaroo crossing signs that just went by, I remember I asked my father, “Dad, how do the kangaroos know that’s where they’re supposed to cross?”

We never got bored. We engaged in guessing games as we travelled on long trips. I spied with my little eye, but only a fraction of the things I could with my fully grown eye. Unlike kids and parents so often today we played as kith and kin.

I remember listening to a Japanese priest on the radio. He said what he thought to be the most appealing Christian slogan . It was ‘The family that plays together stays together’.

’He had replaced the ‘r’ sound in that coined by Father Peyton with a ‘l’.

I thought that his rendering was an even more effective one.

Our town and surrounds was a community where work and friendships firmly interlocked. Tenderfoot me spent school breaks on the land, plenty of room to swing a rope with our friends, the Roberts of Kelvin. I dabbled in bush skills, rolling up my shirtsleeves, putting my back into it, having a crack at everything. Lyle managed the property with his offsider brother Col, as spare as the bush itself, his quarry faced stubbled mush full of leathery old lines, all wrinkly, his hair as knotty as the jumbucks he drove. Each day revolved around the livestock, dictated by routine.

Col’s humble hut, where he batched, was unconnected to electricity, lit by smoky oil lamps and discouragingly limp candles. He would bring a battery into town to be charged so he could listen to the radio during the week.

‘Why do I need electricity? he reasoned. ‘It’s really just organized lightning. I get plenty of that out here.’

He had woken up every morning in his simple home for much of his life. The hut was without indoor plumbing. The cesspit was out at the backside. Pieces of newspaper hung on a nail for toiletry purposes. Washing was done in the outhouse- with a boiler, mangle, starch and blue bags. The wooden kitchen floor slanted left to right. He cooked on a coal stove and had no refrigerator, but somehow he made do. Like the pioneers he fashioned his situation to his needs, whether it be making a rough sawn table for the kitchen from a piece of unplaned timber, building a shelter in the scrub from bark and branches, or husbanding a fire when the leaves were damp.

I had my own go at improvising. Col wondered why I was pulling on and off my pullover repeatedly and vigorously. Why I was rubbing balloons on my head.

‘Static electricity’, I answered, producing that crackling sound, ‘to make things run more easily.’ I never could work out how to harness it for cooking.

The Roberts had one of the bovine ilk. One end was moo, the other, milk. The cow, had a lovely and tolerant nature, and would allow me to milk her. Like Romulus and Remus we often drank straight from her. Any left over was churned into butter. While ruminating on the origins of milking, the inevitable question was posed to me: ‘Who discovered we could get milk from cows, and what did he think he was doing at the time?

I learned from observation such facts as that a cow lies down one half at a time and gets up in reverse.

It is not a graceful movement. She goes down on her front limbs first, one after the other. Then she folds in her rear legs. About six inches above the ground, she lets herself fall, giving herself over to gravity.

I observed how a chicken can still keep moving even after it’s been decapitated. Its large eye sockets mean that there isn’t room inside its skull for all of its brain, so a bit of the brain functions briefly inside the top of the neck.

I learned a lot from their cattle dogs: obedience, loyalty, and the importance of turning around three times before lying down.

Col and Lyle worked very long hours. ‘Remember’, said Col, ‘the earlier we start the better. We work from from ‘can’t’ to ‘can’t.’

‘What times are they ?’

‘From ‘can’t see in the morning’ ’til ‘can’t see at night’.’

Sharing the hut gave me an insight into the backbreaking, dawn to dusk life of a weathered rough and ready farm labourer. Joining him ring-barking trees, clearing scrub for pasture land, mending fences, sinking a dam, rounding up the sheep and cattle. The rootinest, tootinest, shootinest, hootinest little sidekick around, singing ‘move ’em on, head ’em up, head ’em up, move ’em on, count ’em out, ride ’em in, ride ’em in, count ’em out’. Rattling my dags, I threw myself fully into this enterprise. Wrangling the herd towards the corral, we caught each pregnant ewe with a crash dive into the dust.

‘Our family was extremely poor’, Col told me. ‘Clothes were scarce. I sometimes had to pull my socks off after school so Lyle could wear them into town.’

With little schooling, thrown on his own resources, Col’s childhood ended early when he had to shove off from home to grub and sweat for his keep. ‘I went a waltzing matilda everywhere, humping my bluey every day on rough, dusty bush tracks looking for work.

Some days there would be no work and the tramping would have been for nothing. Many others had been on the road for months, walking up and down the country in a maze of jobless refusals. Things were crook on the land. For every job, so many men.

So many men no-one needed. Another day, another nothing. When I could, I rode a horse. The same did duty between the shafts of a sulky when it came time to choof off. I was always without two shillings to rub together. But we always managed to find grub. We lived on rabbit stew.’

‘Boy oh boy, you’ve been a real battler, Col’, I said.

‘Bloody oath’ he said. I’ve never turned a hair at a bit of hard yakka,’ he skited, tall in the saddle.

He was not a sophisticated man, but when he spoke, the words came out like the bricks of a wall built to last.

‘Don’t you feel cut off from life, here in the scrub?’ I asked ‘Don’t you ever feel like a shag on a rock?’

‘No bloody fear,’ he said, resisting the obvious play on my innocent words. ‘No one raises my hackles or bosses me around here. I like the peace and quiet where a man isn’t crowded.’

Wilderness, farmland, desert and country towns, the bush is a place where some people live and others never go. Even though most Australians were going to the surf and turf rather than the bush, it was the mateship and collectivist outlook forged through such isolated hardship which retains a transcendent place in the Australian ethos.

There was the commercial class who operated stores and businesses. Then there were the workers who provided the labour for them and for the coal mine and abattoir. They were the heavy lifters in my eyes.

Stifled by the permeating stench of ammonia from waste in the air, I watched the slaughtermen at work, herding cattle to their deaths, stunning them, then stringing them up on a conveyor belt, cutting their throats, watching them bleed. Later throwing away their inner parts, a hard and for many a horrible job. But for them above all one where they could bust their gut to demonstrate their strength and value.

I observed these workers engaged in their series of daily routines, in the striving and succeeding and failing that make up a life in which, because of poverty, there is little freedom of choice. The quiet nobility of their lives lived with values but without great opportunities. After knocking off work, there was just time to lay that bit of lino on the floor or work on the car before having a few middies and a game of two up at the back of the pub.

My knowledge of such hardworking people, parents of my mates, led me to the credo that work itself be elevated to a place of pride and esteem.

That even if you happened to be in a lower paid or manual job, you were valued for the work you did which was necessary for the functioning of society. Never touching it, my father made more boodle selling coal than the miners who, busting their gut, confronting cave-ins and the deadly black damp deep below the earth’s surface, dark as a dungeon, their lungs full of noxious phlegm, coal dust pitted in their skin, tore it out of the coalface. ‘Gas leaks, fire and water are our daily enemy’ said my friend Colin Sills’ father.’

Accidents showed why in an industry such as mining, you relied on your workmates – both to get the job done safely and to stand up for your rights. The battle was necessarily collective. A single miner possessed no power at all; the miners as a whole, however, could nearly shut down the entire nation, as they’d demonstrated in 1949.

It was while I was in my friend Andy Dall’s house one cold snap I learned about overproduction in the capitalist economy. Shivering he asked his miner father, lying on the couch, ‘Why is it so cold in the house?’

‘We don’t have any coal’, he said, rugged up like the Michelin Man.

‘But why is there no coal?’ Andy wanted to know.

‘Because I got laid off for the rest of the month’, he replied.

Still unsatisfied, Andy asked one more time—‘And why did you get laid off?’

To which he answered, ‘Because there is too much coal.’

Of course, it wasn’t that there was too much coal. It was just that it was all in the hands of his employer, the company that owned it. They were stockpiling their supplies expecting a rise in prices.

‘I made an investment in this country. Where are my dividends?’ asked Andy’s dad.

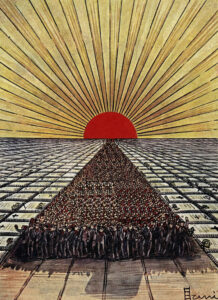

It was just the wisp of an idea at first. Then slowly but surely I came to the conclusion that workers, who produced the goods we needed, who built the town, the railway, ploughed the fields, without whom nothing can move, were the underlying motor and buttressing social stanchions of society and should be placed at the forefront. It was those who did heavy manual work, like miners or farm workers, the salt of the earth, who should enjoy certain privileges, better wages and health care than those in less strenuous or dangerous professions, like office work or managing – and above all those who made money off their backs by merely owning.

When these backs rested, their thrones were less than regal. I’d have run a mile rather than use the outhouse toilets at the homes of some mates. Unconnected to the sewerage, such ‘thunderboxes” were not built over pits. Instead, waste was collected into large cans, or “dunny-cans”, which were positioned under the toilet, to be collected by contractors or “night soil collectors” hired by the local council. Collected waste matter would then be removed from the premises and disposed of elsewhere.

My inchoate political leanings grew into a deep commitment to overcoming the big chasm between those who have and those who don’t.

Between those who run the world and those who make the world run .

As well as between those who dish it out and those who cop it.

There are two kinds of people. Those who divide the world into two kinds of people and those who don’t. I’ll leave it to you, the reader to work out which one I am.

Some of these business and working people were immigrants from The Old Dart and some were from Europe, the latest arrivals to wash ashore. The English were given a particular warm welcome.

They kept their wits, not their nits.

They learned the local slang

About the native fauna.

Many were geared up to venture outside the city.

They went where they were needed

And learned of the tyranny of distance

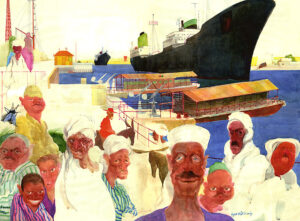

Some learned the great influence of distance on travelling to far-off Australia in 1956. The ships they travelled on had to pass through the Suez Canal.

That year the Canal was closed due to the Suez Crisis.

They found that some things moved differently than they did back home. The rotation of the earth gives rise to an effect that tends to accelerate draining water in a clockwise direction in the Northern hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern.

Some found other movements that could only be explained by indigenous lore.

Skilled, enterprising and happy to please, these ten pound poms and new australians fitted in quickly and were highly valued -more or less.

One bushy who made a packet gambling went to Europe on a holiday. When he returned, I asked him: ‘How did you find it?’

‘It was bonzer, Allan. Such a rip-snorting variety of landscapes – the Mediterranean, Black Forest, fjords and all those interesting old buildings. I even saw Cossack dancers at the Bolshoi.’

‘What were these Soviet people like?’

‘You know what the most amazing thing about them was? They’ve two legs like everyone else.’

And they come in all shapes and sizes.’

‘Would you live in Europe?’

‘You know there’s one thing I would find hard to hack about living there.’

‘And what’s that?’ I asked.

‘There’s too many New Australians.’ he replied. ‘But if I had to, I could live in Switzerland, though it’s very expensive.

‘What would be the best part about living in Switzerland, that peaceful country whose greatest achievement is—-the cuckoo clock!? Would it be the chocolates, the mountains, the fresh air?’

‘I’m not sure, I got into some hot water there in Geneva. I turned on the hotel shower tap labelled C’ and nearly got scalded. Their ‘C’ stands for ‘Chaud’ – French for hot. Still their flag is a big plus.’

‘And the worst thing about living there?’

‘Everything looks perfect on the surface but the people can be quite unfeeling. I was resting in a park while others were walking the dog or playing with children with soccer balls. Suddenly I needed to take a leak and couldn’t find a toilet. I had to do it against a tree. Then I realised everybody had stopped what they were doing abruptly. They were muttering to each other and glaring at me with black looks. One burger told me I should be charged with indecent exposure.’

Of the many who migrated to Australia, uncounted numbers changed occupation, their ambitions encouraged by the openness of Australian society to talented and determined newcomers.

One New Australian decided to have a go at coalmining. The foreman at Blackjack Colliery asked him to join his crew underground gathering pieces of coal and loading them onto rail trolleys. The foreman’s offsider was puzzled to see how awkwardly the new worker was trying to scoop up the pieces. On the long handle of his tool was fitted not a broad blade with upturned sides but a curved bar sharpened at both ends . To explain the misunderstanding the offsider told the foreman how he had instructed the new man.

My Dutch Uncle.

My cousin Beverley came up from Sydney accompanied by her new husband. Tom had migrated to New Holland from Old Holland as a teenager. Our family extended a warm welcome to this fine, wholesome gentleman.

I looked up to Tom. On one level it wasn’t surprising. I was still poised for my final spurt in skeletal growth. I got to wondering if I’d reach his height. I had read that Dutch men were the tallest in the world. My theory on this was based on a crude version of natural selection. As the Netherlands was so small, to all fit in they could only expand upwards. Secondly I reckoned it was also so they could keep their heads above sea level.

On another level, I found Tom to be thoroughly community minded, thrifty, practical and above all possessed of a good sense of humour.

He was interested to learn of my fascination with readings from the Apocrypha.

As an ornament we had a pair of yellow clogs on our mantelpiece which provided an interesting talking point.

Tom had presented Bev, his fiancée with a pair of carved wooden shoes as is the traditional engagement gift.

‘Thanks, my Old Dutch, but no thanks she said.’ I don’t fancy blisters, chipped bones or sucker splinters.

‘I’ll stick with my comfy leather shoes. How about you take me out for the day instead?’

‘O.K. but you’ll have to sit on the handle bars,’’ replied this son of a cycling nation.

This was before he had enough cheese to buy a car.

He took her out for morning tea and biscuits. This was a new experience for her. She had never given blood before.

While at lunch she slipped on some grease and dropped her tray.

In the evening he took her to the picture theatre. At intermission he asked what she would like to partake of. She said, ’Tom, I’d like some fruit and some sweet.’ He came back with an apple on a stick.

I thereby learned the custom of ‘Going Dutch’.

‘Clogs too have had an important place in our heritage,’ Tom explained to us. ‘Back in the day the Dutch landscape, full of bogs and swamps, was very suitable for clogs. They are robust, safe, waterproof, and as an extra bonus: they are cheap too. Our language has many idiomatic expressions associated with klompen.

‘Now my clog is breaking’ is one such saying. It is said in astonishment if something unforeseen happens.’

‘When would you wear them, Tom,’ I asked

I’d wear them whenever I had to keep my feet dry, wooden shoe?

No sooner had he uttered these words than such an opportunity arose.

Dad came into the house crying, ’There’s a crack in the dyke. There’s water flowing everywhere. What can I do? He knew that left untended the crack in the base of the bowl would grow larger, that from a single leak, a terrible breach might grow appreciably. He knew that the water could end up splashing out of the bog, the trickle turning to a torrent.’

‘Now our toilet is breaking,’ I groaned.

Before you could say Hieronymus Bosch, needing no persuasion, Tom slipped on our ornamental clogs and clomped, clicked and clacked to our outhouse. Thinking quickly he plugged the crack with his finger.

What caught my eye was the way he went about it. Although the crack was on the left side of the base, Tom reached his right arm around the back, pivoted while looking back searchingly before applying his finger.

‘Rest assured I’ve got your back, Tom. But wouldn’t it be easier to use your left hand to do this?’

Oh this, ’he replied. ‘force of habit. It’s the ‘Dutch Reach’. When I’m opening a car door, I open the door with the hand furthest from the door handle . That way I can look over my shoulder for cyclists. That way I can check out automatically whatever’s at my rear.’

‘You believe in playing it safe, Tom.’

‘I’m not going to tiptoe round the tulips with you. When you’ve lived through occupation, you never know what brutal behemoth is stomping close by.’

‘Tom’, said Dad,’ I hope you can keep the water in check ’til I can get the plumber.’

‘Bill,’ said Tom, ‘I don’t want to stay stuck out here for hours in this soggy, sweaty heat. I have a simpler solution. Why not just turn the water supply off at the mains?’

‘Of course,’ said Dad. Why didn’t I think of that sooner?’

‘You got a bit flustered, Bill. Keep in mind You know the message at the front of your shop. ‘Keep cool, calm and collect our specials!’ Keep in mind the first part.

‘Three cheers for Tom’, I said, ‘our Dutch uncle has saved the day.’

‘And I’ll save on your specials,’ Tom replied. ‘Some cans of your salmon for sandwiches on our journey home. We Dutchies love a bargain. Who doesn’t?

‘I read that the Dutch spend less than any other Europeans on holidays and festivities,’ said Dad.’

‘Some people might just see this as being more frugal and less materialistic than others. Like many of my compatriots I grew up under the privations of the War. This certainly doesn’t have to mean that we have less fun. Perhaps not spending as much money leaves more room for other ways.’

In keeping with this thinking, it was not surprising that Tom was influenced by the preaching of John Wesley eschewing profanity, espousing personal discipline and abstinence in the consumption of alcoholic beverages.

It was also not surprising that he came to realise the world was changing and that the Church had to adapt. Through education and improvements in people’s living conditions more moderate and enlightened social behaviour would ensue. Two incidents on Tom and Bev’s northern pilgrimage reflected the changing times.

As well as tending our store my father sold fish from the back of an ice packed truck parked beside the Civic Theatre. He used to spruik his goods calling out, ‘Damfish for sale, dam fish for sale.’

Tom asked him why he was calling them ‘dam’ fish.

Dad said, ‘These ones were caught at Keepit Dam, so they’re dam fish.’

He brought some left over home at the end of the day and asked my mother to cook the dam fish.

She looked at him a little bewildered and said, “You shouldn’t use such language in front of Tom.’

‘I’ve explained to Tom why they are called that,’ he said so she agreed to cook them. When dinner was ready and everyone was sitting down, Tom asked me, ‘Please pass me the dam fish.’

I replied, ‘That’s the spirit Tom. Now please pass me the bloody potatoes!’

While Tom was in Gunnedah he attended a service given by one of those old Ministers who rail against alcohol, warning of the fiery furnace.

When he was completing his temperance sermon, with great expression he cried, “If I had all the beer in the world, I’d take the demon drink and throw it into the Namoi River.”

With even greater emphasis, he said, “And if I had all the wine in the world, I’d take it and throw it into the Namoi River.”

And then, finally, he said, “And if I had all the whisky in the world, I’d take it and throw it into the Namoi River.” He sat down.

The song leader then stood very cautiously and announced with a wide smile, “For our closing song, let us sing ‘Shall We Gather At the River.'” from The United Methodist Hymnal Number 723.

An Inquiring Mind.

I was always wanting to learn new things, about what people had to say and how they got to where they were. With an incipient searching point of view, I wanted to know everything about everything.

Articles of Faith

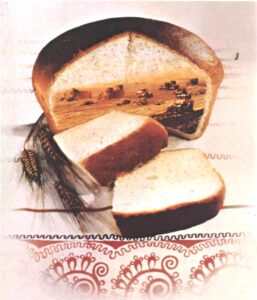

As you might have guessed, ours was a political household. From a tender age politics and history were food and drink to me. And vice versa. It was my grocer father who was the purveyor both of articles of sustenance and of faith. He doled them all out with care : ‘Here’s a half a pound of reasons,’ he told us, ‘and a quarter pound of sense, a small sprig of time and as much of prudence.’

My mother, his right hand woman, went along with whatever he dished up to all intents and purposes.

Items of knowledge about the tea, butter, flour, sugar, spices, tinned foods he trafficked in, were served up at the dinner table as a matter of course, as were the names of those responsible for producing and marketing them.

He told me a great tale about how marketing can work wonders in boosting sales.

‘You know how we sell much more red salmon than pink.’

‘Sure. Red has much more flavour.’

‘Well the advertising men turned this insurmountable handicap around to get ahead of the game. Their client, a cannery stuck with a glut of less marketable pink salmon boldly labelled their product as ‘Guaranteed not to turn red in the can!’

I read the labels on various packaging to sharpen my own wits.

When I first started reading I took things rather literally.

Later when more literate I asked, ‘Dad, how a product could be labelled as ‘new and improved’? ‘If it’s new there has never been anything before it. If it’s an improvement there must have been something before it. What was being passed off then?’’

‘It’s just an advertising technique used to persuade you to buy. We tell people in our advertising that our sale is in it’s last week. That way they’ll be more likely to shop sooner.’

One of our customers wasn’t happy when we used that approach.

‘The ad in the paper said ‘Big Sale. Last Week.’ Why advertise? I already missed it. You’re just rubbing it in.’

Bandied about at our table were the names of the various companies, their workers, the politicians who represented them and what was at stake in their disputes. Coming up for discussion most often was the question of who was running the country, whether it be Ben Chifley, the pipe smoking leader of the Australian Labour Party, who had spoken of the Light on the Hill, or Robert Menzies, protector of imperial values, leader of the Liberal Party, which governed in coalition with the Country Party.

We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.

Henry John Temple, twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century.

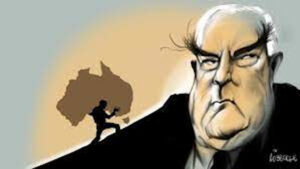

It was Menzies whose nodding acquaintance I made early in 1953-December 10 to be precise, Chifley, having been laid to rest. The formidable Ming as he was known dominated the Australian stage like no one ever has done.

My father took his chip off the old block to witness his performance on his whistle stop, pork barrelling visit to Gunnedah. On the black stump, he was coming to pitch the woo and endorse the government candidates in an upcoming by-election. He could be guaranteed a good turnout in this part of the sticks, seeking assurance of its importance on its part.

It wasn’t everyday that such a notable man of affairs dropped into the state’s northern wheat belt, its breadbasket.

While my father was from a different faith, he knew the good sense of hearing out disparate voices. After all this was the dyed-in–the wool conservative heartland where his business interests required him to tread on eggs as well as sell them.

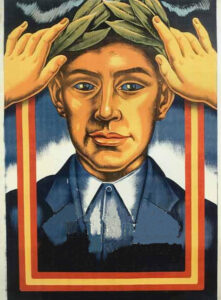

Waiting to file into the town hall, no vetting, no admission by ticket only, we were at the end of the long queue that reached the side entrance when the bestriding figure loomed up. Jumping jellybeans, there was no mistaking this famous head, large as life bending down and up ever so slightly, its dewlaps as pendulous as a sea lion’s, its dark bushy eyebrows even more luxuriant than its crowning white cap.

You could tell this tall man , well proportioned, although with an ample girth, was one who commanded authority by the close attention paid by his minders and the obeisance displayed by those in attendance. He arrived directly after his luncheon. Nothing fancy-just hot tongue and cold shoulder for those his followers found distasteful. Along his path his minions fell over themselves bowing, scraping, curtsying or moving their heads to express their assent.

Not known as ‘a man of the people’, this redoubtable father figure was nevertheless moved by my civic minded presence to bequeath to me words of wisdom. ‘Good evening young fellow, what’s the good word?’ he enquired, ‘Are you winning?’

‘Well, Mr Menzies’, I replied, clearing my throat, eager to make an impression, ‘‘I’ve been having a lucky trot. I’m top of my class at school, I’m happy to say. I get lots of holy cards and koala stamps. Lots for spelling.’

‘Young fellow, there’s no such thing as luck – only an alertness to the opportunities life has to offer you.’

I was on a winning scholastic streak at this stage with pats on the back. ‘Mum and Dad call me a walking encyclopaedia. I’ve got information vegetable, animal, and mineral.’

‘That a boy.’ he said. ‘And do you help your parents?’

‘I assist them in our grocery shop’ I replied, my father beaming beside me.

‘Well done, if I don’t say so myself. So did I. Whatever you do in life always strive to do your best,’ he advised, ‘and you’ll go a long way. Whatever you do always give one hundred percent. Unless you are donating blood. You be good now.’

As he proceeded into the hall, festooned with flags and bunting, my father said to me, putting me on, with his usual term of endearment: ‘You should take him at his word, Allypal. You never know, you might well wind up in his shoes one day’. Alas little did my dad know how true this would be, at least in the physical sense.

Know for his rapier wit and razor tongue – even among his colleagues – in the hush of an appreciable, mostly loyal audience, this heavyweight could lower his guard and leave them sheathed. Those beetlebrows could rest unruffled with no one to bristle at. No one would have dared heckle him. While I did not follow all of his references, his clear simple English and re-cap of the points he was making enabled me to get the drift. He conveyed his views forcefully in his sonorous baritone voice, striking a distinctive pose with his right hand raised and clenched, his other hand on his hip. Absolute silence during his pauses. Not a dicky-bird. Most of his address was self-congratulatory directed towards those who showed the clear solid values that he stood for: industriousness, thriftiness, self-reliance and commitment to family life, parliament and the Queen.

He exalted the home as where the life of the nation was to be found and emphasized the role of women as custodians of this site. To the cheer of ‘Hear, Hear!’, he referred to the audience as ‘the forgotten people – not Rose Watleys mob – but the middle class, whose neglect he put at Labour’s door. Trumpeting his government’s sound management, ‘What we have done is right for Australia’, he said that the proof of the pudding was in the eating. While Australia’s famous ride on the back of the sheep

had come to a halt and prices of world and other agricultural exports were plummeting from their record levels, there were plenty of jobs. If only the unions would toe the line. In their selfish pursuit of greed, they were forcing up costs and stopping competition. They were bullying every worker to become a member. And their ringleader, none other than the leader of the opposition, Dr. Evatt who promoted compulsory unionism. A hypocrite, charged Menzies, because while President of the General Assembly of the United Nations he had championed its Declaration of Human Rights. It declares: ‘No person shall be compelled to join an association”.

In his peroration, Menzies reminded people that they were now foremost in the mind of his government, and that things would pick up even more. Waving glittering promises before their eyes, he told this rural audience that if they worked hard they would be rewarded accordingly.

During the course of his address his audience gave forth great guffaws when he said his opponents had invaded the area like grasshoppers. ‘It is up to you to find out how destructive they are,’ he added.

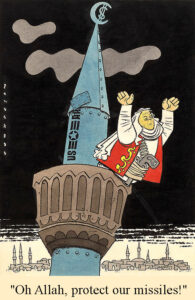

He claimed that the Labour Party led by Dr. Evatt had had their tongues hanging out in the hope of another depression. I picked up on his view that the Communists he said we had on the run in Korea were not to his liking and that ‘we are dealing with them’.

As to what he meant, a nod was as good as a wink to a blind horse.

He knew how to tap into the mood of genial provincial optimism that had settled over middle Australia during these years of unprecedented prosperity.

The funny thing is Dad had a grudging consideration for Menzies. ‘He advanced himself as a self-made man – although he would have been wise to get some help.’

His own beginnings were not unlike that of Menzies: “He wasn’t born with a silver spoon in his mouth. Menzies father ran a grocery store in a country town”, he pointed out to me. “And things weren’t easy. Like you Menzies lived in rooms at the back of the shop”. Typical of Scots of humble origins, Menzies senior respected schooling and nudged his son to avail himself of a scholarship to rise in the world.

My father’s own father had had a saddlery business, a farm and investments in property. Neither my father nor mother completed the final years of their secondary schooling. However, his experience of the hardships of the Depression and of working for others had affected him deeply. ‘This man-made calamity swept across this rich country like a plague. Time was when banks and businesses folded. Farmers, bothered with mortgages, debts, unable to pay their bills lost their plots of land. Workers lost their jobs and their shirts. Debt collectors and money lenders hammered on their doors. So many hands were available that wages were pushed steadily downward. Opportunities for most people dried up. Many of the displaced migrated wherever in search of work’.

Like most people, what concerned him was that once the slack of wartime shortages had been taken up, dole queues, soup kitchens and swagmen vainly scrounging up work would boomerang to the land again. You can guess what I’m going to say next. In the long run he was right, but it would take another thirty years for the capitalist economic engine to start running into big troubles again.

Experience of this crucible convinced him of the value of children, every last one of them, having the best education of which he or she is capable. This would also of reduce social and economic inequalities. Menzies grandfather, a trade unionist miner, taught his grandson the same, but the second part didn’t seem to take root as deeply. That’s where Menzies needed more help.

These things engrained in my father’s thoughts the true belief that through both self improvement and greater equality Australians could ensure that war and depression not happen again. He saw the ALP as the engine of change. His hero had been the unlettered Ben Chifley, who rose from being a railway engine driver to becoming Labour Prime Minister during the last year of the War. I often saw this man of great dignity in photographs and even in newspaper cartoons staring intently through white twirls of pipe smoke. Somehow this suggested to me he was a benevolent, wise man, a man who would not rush into doing hare-brained, worrying things.

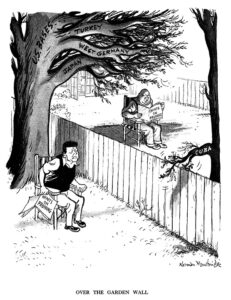

‘There are others who see the way forward to a classless society differently’, he told me when I asked after the subject of a magazine cover. ‘They take a different road than us. There’s been no end of argument about this.’

‘What is this argument about?’

‘It’s an argument about means, not ends. They don’t rule out a violent overthrow of the ruling class whereas we work on the hustings with the ballot box.’

While I was helping renovate our living quarters, peeling back a layer of old linoleum covering the floor, this stripling historical archaeologist unearthed engrossing yellowing, mottled old newspapers used for insulation purposes, including a faded cover of the establishment ‘Australian Women’s Weekly’. It had not seen the light of day for a decade. The portrait, that of a fleshy faced, mustached avuncular man in uniform, pipe in mouth, was labelled Joseph Stalin.

‘He’s the ruler of The Soviet Union, the largest country in the world, one which has nuclear weapons.

He heads up The Communist Party which rules the country without opposition.

The iron curtain he has erected blocks the Union and its satellite states from open contact with the West and its allied states.’

‘So people can’t get into their territory easily.’

‘Nor can they get out. The barrier is impenetrable.’

‘So what is his appeal?’

‘Stalin says Communists are the only ones who can bring peace and prosperity to the world through wraparound state ownership of wealth and the means of distribution.’

‘What does this mean, Dad?’

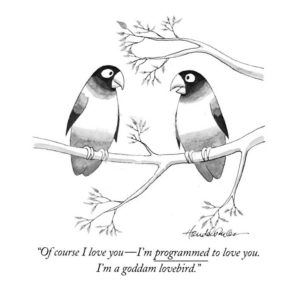

‘It means their government will see to every need. Stalin says they’ve already demolished class differences. He says the solidarity of their workers and farmers will do away with hunger and greed. In the Soviet Union they embody it’s social ideals — mighty workers forging the nation’s well-being with a hammer, side by side with farmers sure to feed the nation with a wheat-cutting sickle.’

’‘Is Stalin really good or bad, Dad?’ I asked, studying this image of an avuncular, thoughtful figure. ‘He looks like someone you can bank on and trust. But Mr. Menzies talks about Communists as our enemy.’

‘During the war when the Soviets were our powerful ally we used to call him “Uncle Joe”. His air force was fighting the Luftwaffe together with British Hurricanes.

Before the War many saw him as a monster. As the 1940s was a fretful time with war and economic difficulties, it seemed good to have such a man in charge of our ally’s affairs. He brought his country from nowhere to become very powerful. His Chinese allies are doing the same. Foreign visitors are struck by the abundance of fruits, vegetables and poultry in all the cities. Beggars, barefoot children, men or women dressed in rags, are now seen only in a blue moon. People there now live with more dignity. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Geoffrey Fisher, put it this way when he visited Australia: ‘Its creed appeals to peoples which have throughout the ages known nothing but semi-starvation and poverty.

They see here a promise of delivery and hope.’

‘Does this mean the Archbishop approves of Communism?’ I asked.

‘No fear. He suspects their intentions.’

‘Weren’t the Communists on the same side as us during the War?’

‘The Soviet Union and the Chinese Communists were our allies when America was still neutral. When it entered the Communists were given reluctantly a temporary pass. The sacrifices of their people helped to turn the tide against the Axis.

With the war all over bar the shouting, we were suddenly led to believe it was the Soviets who wanted to dominate the world.’

‘Do you believe this, Dad?’ I asked.

‘I go along with Doc’, he said. He believes the Soviets are only establishing defensive zones of influence in Eastern Europe, not unlike what he has been trying to get Australia to do in our north. He believes we should develop a positive relationship with the Soviet Union.’

‘So what about Stalin?’

‘That’s not to say Stalin’s a good guy by any means. It’s London to a brick on he was never the kindly man the Woman’s Weekly showed him as. Is he as bad as they say he is now? There are too many horrible stories coming out the Soviet Union to say otherwise. Behind this mask lies a fiend who knows nothing of honour or conscience. They are quite unknown to him. If you don’t obey him you can get sent to a forced labour camp and be mistreated badly.

He rules with an iron fist’, he said, closing his hand, bending his fingers to the palm. ‘The problem is the Communists – like the publishers of The Women’s Weekly – don’t put up with newspapers saying it as it is. The Packer press here accuses The A.L.P. of being in bed with the Communists. The newspaper barons and the companies have so much dough to keep the Liberals and silvertails in power, it seems to grow on trees.’

By bringing to light this paper, something clicked. It was an early lesson for me about political flip flop, how history can be turned on its head, how by blowing hot and cold, yesterday’s goodies can become today’s baddies.

As I matured I traced this back to the Peloponnesian War. I traced it back to the good guy, the Athenians, and the bad guys, the Spartans. And after a while, the Athenians become ruthless and cruel, like the Spartans.

I learned how yesterday’s baddies can become today’s buddies.

I learned how the media can glorify a country we’re backing to vilifying one we oppose.

As I got older I realised we need to adjust this fairy tale perception of conflict as good versus evil. We need to move away from this Little Red Riding Hood pattern, where Little Red Riding Hood was good and the wolf was the bad one.

What did you learn in school today,

Dear little boy of mine?

What did you learn in school today,

Dear little boy of mine?

I learned our Government must be strong;

It’s always right and never wrong;

Our leaders are the finest men

And we elect them again and again.

Pete Seeger.

Doc Comes To Town.

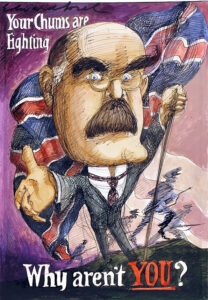

Hot on the heels of Menzies’ flying visit was that of the larrikin leader of the federal opposition, on his barnstorming tour to drum up support for the Labor candidates. The outcome being important for the balance of power, for one week the ticklish national issues were being thrashed out not in Canberra but at our own parish pump. Dad took me to hear out this son of a country publican at the well-attended street meeting the following Friday.

On the way we passed the Commonwealth Bank to which he had accompanied me the previous week, toting my money box.

About a bank I learned that it’s a place that will lend you money, if you can prove that you don’t need it. A place where they lend you an umbrella in fair weather and ask for it back when it begins to rain.

About money, I learned very early there is never enough in creation, that some people have more of it than others, that it determines in many cases how people look at you, talk to you and treat you.

‘Show me how you’ve been saving’, Dad had said’. When I handed it to him he shook it but there was no rattle. It was packed tight.

‘Good for you.’ he said. You know what I say about rainy days.’

How could I forget. It had been on such a day when we had taken shelter in the bank’s classical building in Sydney. It was in its likeness that my uniquely designed Heritage pressed tin container was printed and shaped.

‘People recognise this model, like the bank ’, he said, squeezing the sides of the tin without being able to bend them, ‘as something substantial, constant, and reliable.

These boxes were sealed, without an opening for small fingered temptation. Unlike today when personal savings count for little and financial credit and spending for everything, people were encouraged to actively put aside. Upon my handing the tin to the teller, he proceeded to rip it open and disgorge the contents. He then handed me a new one.

Dad told me on the way home, ‘Like your box, unlike the private banks, The Commonwealth belongs to the Australian people. Chifley and Evatt tried to have them all publicly owned. They moved to nationalize them to serve as a model. They wanted the elected government, not the private bankers, to direct the course of the nation’s economy. They had done this to steer us through the war. And what direction would that be that?’

‘Straight ahead, on the up and up’, I said stretching my arm forward and curving it upwards.

‘Too right.’

‘And how do you think the bankers responded?’

‘I bet they didn’t like that.’

‘They kicked up one hell of a stink’ he said, pinching his nose. ‘So strong, I wouldn’t wrap fish in it. Before the last election these enemies of Labour made much it as signs of— ‘creeping Communism, he said putting on a scary voice and face.’ They spent big bikkies in a publicity campaign to scare people. They marshalled bank clerks to demonstrate in the street and at public meetings. Supporters feared being stabbed to death by a fountain pen.’ he jested. ‘Even though it was popular, many people remember the bankers from the Depression as greedy bloodsuckers who drove people out of their homes for not making their payments. Shylocks who produce nothing. Labour lost.’

‘So Menzies had the private bankers in his corner’. I said. ‘Always circling each other, he and Evatt must be very different kinds of men’.

‘On the face of it, they are alike. Like Menzies, Evatt is a legal eagle. Both chose public life instead of enriching themselves through the law. They are both silks, having reached the acme of their profession. But there the similarity stops. Menzies is as cunning as a fox. He can pull a swifty as niftily as Doc’s dad could pull a beer. He could find a loophole in The Ten Commandments. He could then turn it into a noose.’

What does he stand for?’

‘He used to stand for something but eventually stands only for Menzies.

‘Which groups does he aim at capturing?’

‘His appeal is to what he sees as the great sober middle class, the ‘forgotten class’ he talks of. He credits them as the real Australians, having the strong arms of “lifters”‘, he said, flexing his biceps, ‘instead of the flabby bellies of “leaners”.

He plays them off against those he portrays as the monied and powerful on the one hand, and the unionised working class on the other. He wants better paid workers to see themselves as middle class.’

‘The working class can kiss my arse, I’ve got the foreman’s job at last’, I said, getting the drift, echoing and amplifying cynical comments I had picked up around the traps. ‘Working class! These layabouts are so lazy, they can’t even spell it. So lazy they can’t even fake working. They’ll never get to the top sitting on their bottom. Like those employed by the council. How do they earn their keep? Those bludgers have never done an honest day’s work in their lives.

‘It’s alright for some. Look at that one,’ I pointed out to him when we were driving around.

‘He’s doing the work of two men. Abbot and Costello. Come on Australia, Tote those planks! Lift those bales! They never seem to be doing anything, and yet they do not like to be disturbed at it. Some are like blisters. They don’t show up until the work is done. People say nothing is impossible, but they do it every day. Yet they want something in return. Work fascinates them – they can look at it for hours! Where are those elbows and backs? Why can’t they put some muscle into it? Are they afraid they’ll wear themselves out? All the time their foremen can be heard urging them in vain, ‘Don’t just sit there. Give me a hand!’ They wouldn’t work in an iron lung,’ I said, bunging it on.’ They say it’s against their religion. Some of them are like blisters. They don’t show up until the work is done. They think manual labour is a Spanish worker. They lean on their shovels in the fresh air while honourable accountants sweat in their offices lifting their pens and businessmen break their backs lifting their takings.’

‘You’ve got it, Al,’ he said, a little surprised at my precocious parroting. “They don’t have the Protestant work ethic.’

‘What about the Catholic work ethic?’

‘They have that. They don’t work more than they have to but feel very guilty about it. Of course, every individual worker faces hard work differently. How they approach it spotlights their character: some turn up their sleeves, some turn up their noses, and some don’t turn up at all. As for Doc’s work, he’s, in principle, dedicated to doing away with poverty and unemployment. He sees them as the worst menace to peace. Menzies wants things to be kept the same through free enterprise. Free of government control. Evatt wants social change to be achieved through a strengthened central government.’

‘Like in the Soviet Union?’ I asked earnestly.

‘Nowhere to that extent,’ he answered. ‘I share Doc’s faith and reliance in our existing political and legal order. My money’s on us achieving social and economic reform within our institutional framework. I’m of the firm belief that we can achieve social and economic reform within our institutional framework. We can legislate socialism into existence and capitalism out of it. A violent overthrow of capitalism could lead to more problems than it solves.’

‘What has Doc done in the way of improving things?’ I asked.

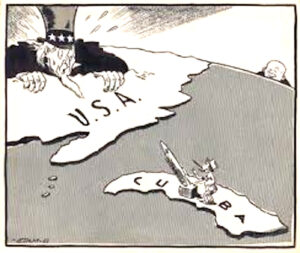

‘He’s really shone on on the world stage. As Australia’s foreign minister, he worked to make Australia an independent nation in the Asia Pacific region, with its own voice. He learned during the war that we have to stand on our own two feet. Our American cousins promised him more planes for us but never came through with the delivery. Like piecrust their promises were meant to be broken. He discovered both Britain and America were committed to a ‘beat Hitler first’ strategy. They made decisions that affected us without consulting us.’ ‘How did he help us stand on our own two feet?’

‘From his years in office, he has left two lasting contributions to our security that really stand out. The first was to swing Australia behind the Indonesian Republic, to help it become independent from the Netherlands. He believes creating fast stable allies near to home safeguards Australia’s northern approaches and means a better defence for Australia. We can’t forget the little resistance the Japanese encountered as they marched down through Asia. I never want to see you having to go through what we did,’ he assured me, putting his hand on my shoulder.

‘And the second?’

‘Doc Evatt’s’ other big part was in the founding of the United Nations whose charter he witnessed the signing of.

He took on the task of fighting for the rights of the smaller powers. This gave the ‘big boys’ who stacked the odds against them the pip. They saw him as impertinent.

‘How does Menzies see him,’ I asked?’

‘As for his main adversary, there’s no love lost between these two’, he said. ‘During the war, Menzies and Co. dished the dirt that Doc was fleeing the Japanese when he attended talks with our allies.

‘Gosh, Dad that’s terrible’, I said.

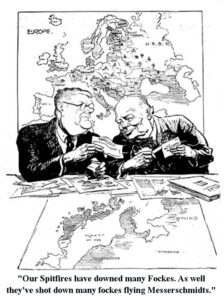

‘He was there to argue Australia’s case. Never let it be said Doc was in in any way, shape, or form yellow’, he scoffed. ‘He was constantly flying the Pacific in Navy planes that could be shot down at any given time. After he and Churchill appraised the global situation together, the British PM Churchill promised to send Australia three squadrons of Spitfires which had been successfully taking on the Luftwaffe’s fearsome Fockes.’

‘Nevertheless they made false and damaging statements about him.’

‘It wasn’t just about the course of the war. He always attracted the worst kind of vicious scuttlebutt. From those who should have known better. Archbishop Duhig said in 1942 he regarded Evatt “as the most dangerous man in Australia, an out-and-out Communist in sympathy, anti-religious and particularly anti-Catholic”. And the mud stuck. But who was he to talk? He and other knockers were all for Franco and Mussolini at the time. Because they were taking on the Communists.’

‘I thought Franco was on our side,’ I said. ‘Some of the nuns and priests speak highly of him.’

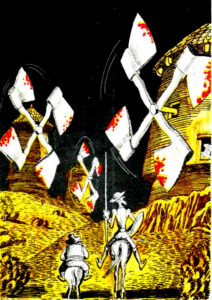

‘ He’s not in my family album. Franco brought in Moorish infidel troops to put down the democratically elected Spanish government,’ he replied. ‘Hitler sent his planes to bomb the loyalists, most of whom were Catholics in name.

But he’s on our side. Work that one out.’

I did- but it would take a bit longer.

I would find out the US overlooked his past and were comfortable dealing with him as long as he allowed them military bases in Spain.

It and the Church, I would learn, had a lot to answer for soft pedalling fascism.

We reached the designated meeting place where a crowd had gathered and we squeezed through for a ringside view. It was just about time for the return bout. We waited expectantly, me on tiptoes, for the bare-knuckle contender to take on Menzies, his reply in their stem-winding stoush.

It wasn’t over fashion. Just as well. In all his visits to London, Norman Hartnell’s had not been part of his itinerary. Clothes-wise he was lagging, his suit it was sagging. The rumpled contender turned up, pressing the flesh, wearing a plain baggy grey suit that hung on him loosely, his hand clasping a large grey felt hat. After an introduction by the local ALP party representative, the Maitland Militant took up his position. His delivery platform was no less the tailgate of a utility vehicle. However, as a sharp speaker, Menzies had his match in Evatt. The stocky, broad-shouldered figure of earlier years was acquiring a paunch, but spoke with a punch, with a carefully cultivated broad, nasal, flat-toned, proletarian twang. In concise, understandable language, this stormy petrel parried Menzies’ earlier thrusts, getting stuck into the government’s policies and answering a host of curly questions bluntly with conviction. While Menzies was not present, a sprinkling of his barrackers were on hand to badger Doc.

‘We’ve got to stop the sale or sabotage of successful public enterprises’ he cried, going on the attack.

‘Well stone the flaming crows, what’s it to you?’ one impudent heckler chiacked from the back.

‘Most of us lose by it’, Doc said matter-of-factly. ‘In each case the area of exploitation is widened because the safeguards against monopoly-namely competition by successful undertaking – have been removed. These belong to the people. That’s about it.’ he declared. He didn’t hold back exposing the motives of his coalition rivals. He declared that despite their name changes, today more than ever they represented the almost unbridled financial power of a few wealthy trusts, combines and monopolies.

‘What’s in it for you? ‘the heckler continued.

‘A wigwam for a goose’s bridle,’ shot back The Doc, realising the extent of the heckler’s maturity. ‘Do you want to try it on?’

His offsider obviously did. This ruddy faced mug lair in gabardine riding breeches and polished riding boots craked, “What are ya? If you don’t like it here, go back to Russia!”

Without skipping a beat, Doc ignored this, refusing to become unstuck by such distracting ratbaggery.

‘You’re all about sharing wealth’, cried the lair. ‘If you had two cars, would you give me one.’

‘Nothing of the sort. But if I had two brains, I’d give you one, sport,’ replied Doc, cutting him off at the knees. ‘Now where was I? Of course, this power is why these bigshots have imposed the ‘wool grab’ ’. Doc picked up, referring to the tax on wool producers. ‘This is why they’ve broken their solemn promise to impose an excess profits tax on wealthy corporations.’

‘Political promises, ‘cried one supporter, in one year and out the next!’

They’ve let prices run away. These groups believe in one freedom – the freedom to exploit the rest of the community.’

‘Bullshit!’ cawed the the first taunter raucously.

‘Ah, my friends, we have an artist in our midst. I’ll come back to your chosen field of interest in a second, Sir’, said The Doc without batting an eyelid.

At the bidding of a few wealthy graziers, the Country Party has scuttled our policy of bringing more industry to the bush.

The second moleskinned heckler cawed once again derisively, ‘ Bullshit!’

Unruffled, The Doc put this silage heap in his place: ‘ I assure you, old son, there’ll be more of this than you can handle. As with grain handling, we’ve decentralised slaughtering and this will continue. The Country Party is afraid this trend will tip the voting balance of power in our favour. ‘They’ve become the slave of the Liberals, hardly serving country interests at all. It’s nothing to crow about.’

‘So what have you got to be proud of? You lack the sharp thinking of Bob Menzies. He thinks quickly, intelligently, and accurately, with a keen awareness of detail and a capacity for insightful analysis. He has a mind that is agile, perceptive, and able to grasp concepts and situations quickly.’

‘I have to admit he does has a mind like lightning. One quick flash of light and then total darkness.’

Strong stuff indeed in these days of obsequious laborite subservience. Where its leaders say one thing and do another, their words not matching their deeds. Overall, most of the people who showed up to seemed to be Doc supporters. They gave it up for him when he laid into the Liberals. They gave him a thirty second standing ovation, as if to send word to Heckle and Jeckle.