The Matriculant

Rejoice, O young man, in thy youth; and let thy heart cheer thee in the days of thy youth, and walk in the ways of thine heart, and in the sight of thine eyes.

Ecclesiastes 11:9

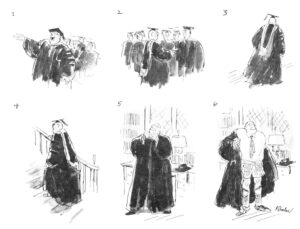

It was in the idyllic bush setting of the University of New England where, with a straight bat, I would embark uninterrupted on my maiden voyage of self discovery. I had never seen so much corduroy in the one place. For some it was their second skin, with complementary scarf and pullover. Layered over this with a roomy fit went the duffle coat. With its characteristic hood, reinforced shoulders, and toggle buttons duffle coats had achieved cult status among college students and intellectuals. The thick, combed woollen mix was extremely wind-resistant. It was ideal for the bracing New England environment which kept one alert, sharpened the brain and gave one an extra sense of perception. Although a loose coat like this doesn’t trap heat inside, the lack of wind chill was extremely welcome.

Putting away my childish things, this was where my world view would seriously take shape. I was the first member of my extended family to go to university. Bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, soft around the edges, I grazed contentedly on my chosen fields of knowledge, betaking myself ahead to where I wanted to go in leaps and bounds, like the kangaroos I passed on the way to classes.

In this natural progression, I completed studies in Economics, English, History and in Education where I would begin to bring all my catholic ideas together. For me it was just as important to understand the world around me and why it wagged as it did, as it was to understand myself and my place in it.

I took to scholarship like the ducks to Lake Zot, the on campus man made water feature.

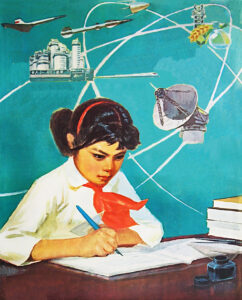

In history my interest lay in understanding the origins of man and ancient society, in understanding the global forces at play in shaping international relations, and in following the progress of the space race. History in the making.

The first rural university in Australia, UNE, an offshoot of the University of Sydney, has gained its own share of prestige, particularly in the agricultural sciences. The other career path it led graduates along were in industry and commerce.

My professional grooming in this seeding ground for professional identities would afford me qualifications recognized at home and abroad. First I would have to furnish myself with a basic degree.

At the heart of UNE’s success is the traditional collegiate system which is an integral part of its character. It introduced fresh faced callow me to a body of bright and brainy young sparks drawn from a broad spectrum of schools and countries – eligible by dint of our common capacity to swot.

This was a community in which scholarship flourished as best could be expected, where we could put our heads together to sift through ideas and opinions and hammer out our convictions in an atmosphere of tolerance and friendship. To say nothing of some getting off on having their heads hammered together in a scrum.

Because of its small size and emphasis I was afforded supportive personal attention in my initiation and progress in the academic environment. I felt right at home. There was a close relationship between teachers and students. All this led to the best student learning experience.

Moreover, consideration was paid to my personal welfare. Such encouragement helped me find my feet. Enabling my smooth transition from the high school regimen of compulsion to one where I was left to my own devices, it was the cornerstone of my fair to middling the undergraduate attainments. I appreciated this tremendously and was determined to make the most of it. Strongly motivated, proficient, but no whiz kid, I had no time to fritter away with fiddle faddle. I had to concentrate not dissipate. I came to study and one way or another study I did.

I couldn’t afford to flop or flounder in this demanding new world. For every student with a spark of brilliance, there are about ten with ignition trouble. After proving I was sound in wind and limb as well as sound in mind and character, I hoped to be accepted as a trainee teacher by the Department of Education. This would save me going through the graduate’s gamble on the labour market.

The first student residence to be built on the campus, Wright College, named after the university’s founder, was to be my home for the next four years. The colleges function as the primary housing, dining, and social organization for undergraduate students. Wright’s five white double storey wooden blocks, named after the first five Greek letters, were only marked down as makeshift accommodation but their use by date kept being stretched forward in time.

Their windows opened onto what had to one of the most impressive backyards in Australia – green, spacious attractively landscaped grounds blending into playing fields and seventy four hectares of heritage parklands, effectively running less than one student to the acre, with the beautiful Booloominbah at the centre and heart of it all.

All conducive to tackling both intellectual problems and sporting opponents. This bucolic setting belied the fact that the main university facilities lay within a hop, step and a jump. Classes were small. This was no degree factory. Scholars have rarely had it so good.

I revelled in what our upcoming Vice Chancellor Zelman Cowen described as ‘the blazing richness of life.’

A cross-section of the parent university – with the lamentable exception of the fairer sex – Wright College prided itself on its esprit de corps. It built this up through a wide range of activities – sporting matches, balls, dinners and debates.

The standard of debating was very high. Too high for me, an absolute beginner. I considered joining the College team, but somebody talked me out of it.

These activities and everyday matters of concern to the student were coordinated through councils The College fostered a lively fraternal atmosphere, anodyne but never staid – ensuring that all students were known, one by one, that no one was anonymous.

The Master of Many Tongues.

On introducing me to Wright College , the Master, Alan Treloar,

stood up from his office chair, put his hand out and welcomed me, ‘Take a seat, Allan. take the weight off your feet. ’

A reserved and dignified man, he was dressed ready to give a lecture. Over his crisp white shirt and discreetly patterned tie, his tweed jacket, and tailored trousers, he wore a simple black academic gown. An Oxford cap, the legacy of his time as Rhodes Scholar at New College, Oxford, lay on the desk in front of him.

‘ It’s a real honour to meet you, Mr. Treloar. ’I said, grasping his hand firmly.’

‘Hey shake it, don’t break it.’

Courteous, helpful, and profoundly knowledgeable, he explained the workings of the College to me.

Alan Treloar was one of Australia’s greatest linguists and classical scholars. Few could rival his knowledge as a scholar of ancient Greek and Latin.

I said to him, ‘I believe Australia has the fewest number of people who speak Latin per capita.’

‘Of course, that depends whereabouts you’re thinking about specifically?’

‘I’m talking about Gunnedah, Echuca and Toowoomba et cetera, et cetera.’

“Yes, what you say about them would be true vis a vis Sydney.’

At Oxford, he had chosen to read classical moderations and greats.

As well as supporting a tried and true system of self-government, his role was to help cultivate a variety of cultural and intellectual interests among the students. He had a special interest in the Roman poet Horace- best known today for his Odes- which often celebrate common events such as proposing a drink or wishing a friend a safe journey.

I was serving post prandial cocktails in the the Common Room on the occasion of the new Vice Chancellor’s first visit. Mr. Treloar asked me for a ‘martinus’.

‘You mean ‘martini?’ queried Zelman Cowen.

He replied,’ One will do the trick, Zelman. I’ll let young Allan here know when I want more.’

Mr. Treloar had read the entire classical literatures of both Latin and Greek at least twice. Among many other remarkable feats he could compose Latin verse in the most challenging lyric metres, a skill few individuals master in any generation.

To demonstrate he was no slouch himself when it came to languages, Zelman asked me, ‘Two Martinis, bitte schoen’.

‘ Dry?’

‘Nein, Zwei!’

I made many friends and acquaintances in short order with no shortage of others whose interests matched my own. Living with like-minded students allowed me to easily share knowledge about assignments and essays and ask advice when confronted with academic or course related problems. Senior students often gave personal advice about the talking points they found interesting, the lecturers they found engaging and tips about past exams – information that couldn’t be found inside a handbook. Around exam period my peers and I could often be found in the library or in tutorial rooms comparing notes, studying together or finishing group assignments.

It also meant that there were people to go to lectures with and share late night discussions. Perhaps more importantly, however, it made it easy to rub elbows with people across a range of disciplines, with different experiences, talents, and goals. – diversifying friendship groups and allowing a more rounded approach to university life.

They shared their stories — of beginnings and challenges, landmarks and turning points. In so doing, they provided me with a unique perspective on the roads we, as a country, have travelled.

Finding my feet, I got into the academic rhythm in earnest, passing my days bustling round lecture theatres and tutorial rooms, retreating to my quarters for frenzied bouts of writing and hitting the books left, right and centre.

Interspersed with lobbing in on friends or vice versa – entering into discourse of all kinds, running ideas by them, toing and froing into the wee hours of the morning, listening to music, sharing tucker and, playing games.

I loved all the neat tricks of playing snooker and billiards. I really miss these though I’m not sure if I miss them on purpose.

Floreat Wright.

Coming the Raw Prawn.

When I met Rick Lay at the beginning of term he was swaybacked and his legs were buckling under the weight of his bulging suitcase which he was lugging up the stairs. ‘I always wanted longer arms,’ he said.

Lending him a hand, I couldn’t believe how heavy it was.

“What have you got in here – bars of gold? I asked.

“Better” he replied, “Sugar and spice and everything nice”.

Upon depositing the suitcase in the room, it popped open with a slight touch of the catch. Bursting at the seam with all kinds of packets, jars and cans, a strange sharp aroma emanated from within making my nostrils twitch.

“What I have down here is the essential part of my identity.” he said, reaching into the case. Rummaging around for what I expected to be his passport, he fished out a package that smelled like the source of that powerful odour. Un-wrapping several layers of plastic revealed the shape of a bar covered in paper. Peeling back the corner, Rick handed it over for my perusal. What then ensured I can only describe as a full frontal assault on my senses. “Holy mackerel”, I thought to myself, “‘What have we here? This dark sticky substance resembles the hashish I saw pictured in a copy of the National Geographic. Was this one of those ‘dope freaks’ I had read about.

My suspicions seemed borne out by the stuff’s olfactory effect. Stinking to high heaven, it nearly bowled me over. Was this the so called ‘high’ that I had heard about? What kind of fishy business was this? Was he coming the raw prawn, Aussie slang for having someone on? Noting my concern, Rick put my mind to rest, explaining the matter at hand. “This is fermented shrimp paste. It blends wonderfully with the robust flavours of chillies, garlic, fragrant spices and aromatic herbs. A little goes a long way”. “I’m not surprised”, I said to myself, “so should I”. Rick said “We Asians appreciate the prodigal amount and quality of food here in Australia but feel you lack a lot with regard to flavour. Being poorer than Australians we have to be more resourceful and inventive in our cooking. We get homesick for our customary dishes and make sure we bring a supply of our seasoning agents and condiments when we come here to study. I’m sure you’ll join us and enjoy a break from the college kitchen”.

Hot Stuff

It was the sizzling sounds that first put me onto the whereabouts of Epsilon’s kitchenette. Then, the air heavy with it, titillating my jaded nostrils, the scent of piquant flavours wafting through the corridors, leading me to sniff out their sauce. Pungent curry bubbling away in a melting pot of race’s and culinary influences. Steaming away was the blander stuff – the vegetables and rice so reliant on this rich concoction. ‘Double, double toil and trouble, Fire burn, and cauldron bubble’, incanted a figure stirring a large pot. Through this mist I made out the shape of David Evans, a highly visible agent of supportiveness amongst collegians from overseas, who had been pointed out to me in this respect. Surrounded by a posse of such students he greeted me “Welcome to Australasia!” emphasizing the latter part of this archaic geographic entity, stretching its ambit somewhat.

He introduced me in turn to this black and brindle band from various corners of the region. They were expressing their sense of difference from each other through comments about such dining niceties as whether to use spoons or just fingers to scrape up their portions. “Feel free to sample some honest-to-goodness Indonesian nosh” he invited lackadaisically. ‘Tuck in. You’re in for a real treat, fit for a Javanese sultan. Wrap your chops around this. It’ll put hairs on your chest”.

I started to probe this offering gingerly, just a smidgen. ‘Well I’ll be blowed. It was nothing if not hair-raising. It was several orders of magnitude more fiery than anything that had ever passed my lips. Where was the fire extinguisher? Was it possible to burn out taste buds? Pressing on, gulping down water to take off the edge, I sweated it out, my palate burning from the unmistakable sting of chillies and god knows what other seasonings.

One of these turned out to be nothing other than shrimp paste. “And how do you find your first taste of Indonesia?” queried David, paraphrasing the question put to the infamous heroine Becky Sharp on being introduced to Indian curry. I couldn’t in all honesty manage ‘Delicious’ as had Thackeray’s neophyte from ‘Vanity Fair.’ trying to ingratiate herself. “I’ll stick to my hair shirt, thank you” I grimaced, choking back my tears, declining the chili offered to ‘chill’ my interior.

David’s response owed more to Russian literature than the ‘Vanity Fair’ he taught. “A budding Solzhenitchen eh!” quipped David, playing on the name of the ascetic Russian writer and his mortifying habit. “Do yourself a flavour. Give it a little time to agree with you” he urged. “You’ll come around to it. Let your enzymes do their work. Once you get past the initial kick, you’ll never again consider denying your taste buds such an earthly pleasure”. Slowly but surely as the heat subsided and a mellow tingling glow settled over me I sensed what he was on about. Real curry was like so many tastes – an acquired one which you had to be exposed to in stages. Nowadays after so many have acquired a taste for it, it commands an established place on the menu .

I was amazed that anything containing shrimp paste could taste so good.

‘It’s the same with oysters. Some say at first they want their food dead. Not sick, not wounded, dead. Then they can’t get enough. So how do you feel now?” he asked, nothing the change in my face. “Itchen, David, itchen to come back to your kitchen”.

Lingua Franca

The college dining room was the ideal arena for my scintillating intellectual confab with all comers. In this meeting place of minds, students and members of faculties mixed freely. Although there was a designated ‘high table’, most Fellows chose where to sit on non-formal occasions, partaking of the same hearty conversational fare as we undergrads. To supplement my modest stipend, I waited on the elevated table on formal occasions, enabling me to size up these men of learning and to observe how they interacted with others from different disciplines, and with simpler minds such as myself.

Amid this fellowship, one stood out as embodying the collegiate spirit of promoting both the personal and academic welfare of students. David Evans, a non-residential member from the English faculty, straddling the social and cultural gulf of town and gown, went the extra mile. A former high school teacher, David bewildered and excited students with his deep silences, teasing speculations and appreciative chuckles. He took great trouble with his students, had a shrewd judgement of them, and was much appreciated by them.

‘How’s that memory of yours working?’ he asked as I lay on a couch in the Common Room, going over in my mind my preparation for the upcoming English examination. Are you in a good pensive mood? Are all the right words flashing on your inward eye?’

‘Some people in their sleep count sheep sprightly prancing and tossing their heads,’ I replied. ‘Like Wordsworth I now count daffodils, their yellow heads gaily reeling and dancing in the wind .’

‘Then since they please your recall should be but a breeze.’

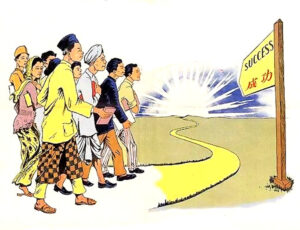

He eschewed the notion of the university as an ivory tower, rather building on its communal character in practical terms to promote better understanding between the people of Australia and those of our neighbours.

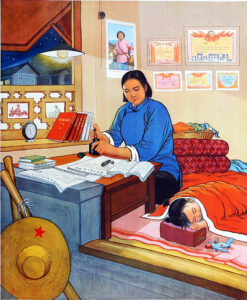

David had taken upon himself on the role as mentor and friend of Indonesian and other overseas students. Starting from a desire to alleviate the difficulties of these young people living in an unfamiliar culture. He told me he wanted to go beyond the occasional easy lofty gestures and cheap grace, actually spending some time trying to some social good. Being in a position to liaise with the university as to what reading was required of his fold, he assisted them with their scriptural work.

Our paths crossed frequently around the lecture halls and on the evenings at college when he helped students refine their English. Running across David one Friday evening, I expressed an interest in his activities along with my desire to deepen my understanding of literature. “Why don’t you join me for a meal at the local Chinese and we’ll put our heads together? While you fill up, I‘ll fill you in on what I do. Do you like Chinese food?”.

‘Is there any other kind?’ I was more than happy to take him up on this, fain to gain the company of a seasoned litterateur, receive his wise counsel and bounce ideas I was working out off him.

Well worn, chintzy and unassuming, the restaurant still made an effort to conjure up an oriental ambience what with its traditional lanterns, chipped willow pattern dinner service’ and red, gold and green décor.

‘If we were now in Peking, said David, ‘You wouldn’t notice the golds and greens. Traditionally red symbolizes joy and prosperity for the Chinese, but now the the revolution’s palette seems to follow this trope religiously. It’s the dominant color, infusing practically everything.’

Pride of place on the restaurant wall was taken by a large handing scroll painting, the subject of which would set the prevailing note of David’s explanation.

While waiting to order, David introduced the group depicted in the painting. “Sitting on the throne, holding court, is Wen Chung, arbiter of the fate of scholars” he said. “Because of their long emphasis on scholasticism and the high status placed on the literati, it is only natural that the Chinese have a god of literature and scholars. Deified from the soul of a student, failed by the Emperor on account of his disfigured face, the Chinese make much of his influence. Seated facing Wen Chang to one side is Kuei Hsing Minister of Literary Affairs on the World, conferrer of degrees and diplomas to whom students prayed for success in exams. My students from the Chinese diaspora have bestowed this honorific title upon me, of which I am touchingly proud”.

“Facing Wen Chang on the other wide is Chu-I, Minister Who Looks After the Welfare of Students.

Chu-I, regarded as protector of those close to the borderline, is also know as Mr. Red Coat. This is a mantle you might wish to assume. Unless I’m very much mistaken by spreading the words you would fill the bill. But first let me explain what deeds it entails”. David proceeded to outline to me the operations of his informal personal peer and staff support network and some of the difficulties faced by his charges.

“Allan,” he said, “if native speakers such as yourself have stresses enough keeping up with work and coping with life at uni., think of the lot of the students from abroad.

They have extra drawbacks through deficits in their language and cultural skills. “They usually know quite a bit about English grammar before they come – maybe more than native speakers – but when the time comes for them to talk in class, they’re not too sure of themselves. They need to be able to speak comfortably in public”.

“Ongoing language support is the alpha and omega for these students’ progress.

As it is they are over saddled with the quantity of required reading, full of the screaming abdabs about competing with native speakers, facing the risk of flunking and flubbing, plain loneliness and a yen for home. They are in an alien land without the support of extended family. They are surrounded by strangers who hold seemingly free and easy attitudes to matters like sex, that are in direct conflict with traditional values back home. Australian informality contrasts sharply with their stricter codes based on respect and harmony. Asians generally frown on the swilling, overt lustfulness and rollicking bacchanalia that our boys get up to, whereas they in turn are seen as blue nose spoilsports and swots.

‘They’re not wowsers are they.’

‘Nothing of the kind. They don’t attempt to force their own morality on everyone. They are just more reserved. They are too often backward in coming forward to seek advice from peers and tutors. Their concern is to maintain face. This is where you could come in Allan, if you don’t have too much on your plate.’

‘I don’t, but I think he or she has – wherever they are,’ I said quietly nodding to the bowls of of soup and rice and mountain of roasted suckling pig sitting untouched on the adjoining table, in front of an empty chair, long after the large family of Chinese diners had started hoeing into their dishes. A couple of other diners had noticed it too and couldn’t contain their bemusement.

‘In discouraging waste, my father always spoke of the undernourished poor in China. He reminded me with his own Confucian saying: ‘Man with one chopstick go hungry’.

Looking at the difficulty some of our fellow diners had in wielding theirs, I thought many like them would go hungry even with two.

Dad extolled the Chinese cuisine with its preparation of small cut up pieces for facilitating careful chewing : ‘Each morsel you eat, if you’d be wise, don’t gobble your food or prize it by its size’.

‘This time is an exception for the Chinese. Now is the Festival of the Ghosts ’, said David. ‘During this time, the gates of hell are opened up and ghosts are free to roam the earth where they seek food and entertainment.

People put out plates of food to please the spirits of the deceased, to celebrate their return to earth, and ward off bad luck. This symbolises the continuity of the living and the dead.’

‘Some people laugh at this, I notice.’

‘They think that Chinese lives are controlled by childish fear. They’re dismissive of what they see as old wives’ tales persisting in the culture of such a long-lasting civilisation. They see it as wasteful contrasting it by association with their own pragmatism and level-headedness.’

‘It doesn’t seem so different to the medieval myths and superstitions I was brought up with. Not so many years ago, I wouldn’t have dared eating meat on this day of the week. And I believed when swallowing the communion, I was eating the body of an invisible dead man doubling as a holy ghost. An all seeing, all beneficent sage living in the sky who watches everything we do every minute of every day with a list of ten specific things he doesn’t want us to do. I worried about the souls of the faithful parked in purgatory. At death I was led to believe they had not been cleansed from temporal punishment due to venial sins and from attachment to mortal sins. I believed that after Judgement Day they’d be in night gowns and snowy white wings, dancing on a cloud with fairies. Through the sacrifice of the mass on All Souls Day and strenuous candle burning, lauds and vespers, I believed I could help push them over the finish line to attain the beatific vision in heaven.’

“Beliefs like this go back through early Christianity and other creeds to pagan times. It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Souls Day. All Hallows’ Eve, which became Halloween, provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognised by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes to disguise their identities. It’s customary still in parts of Europe to lay out offerings of food then for the dead.”

‘ ‘I’m sure even those who see laying out food for the ghosts as wasteful splash out on buying bouquets and wreaths for their own dead.’

David and I exchanged smiles as the family were leaving. At the door the restaurateur was handing them their doggy bags, exhorting them to keep in mind the confucian virtue of considered fletcherism: ‘Don’t forget, many a man can gorge but Fu Manchu.’

Before we left the waitress brought us a a little book in which she had placed our bill. ‘What is this?’ I thought, ‘Mr. Redcoat’s Concise Guide to Chinese culture? ‘Once upon a time there were many starving people in the far off Cathay.’ And what is this? A little gold tassle hanging down? Am I graduating from the restaurant? Is this about teaching English as a second language?

‘Seeing as you have common interests and share activities with many under my tutelage,’ David picked up, ‘why don’t you accompany me on my circuit?’

I placed my soup spoon down carefully, for as you may imagine, he had secured my full attention at that particular moment. ‘By going over the same ground as me with your wide lexicon, clear precise diction and art of conversation, my efforts will be consolidated. While they won’t be composing sonnets in a week, this could help me raise their communication skills to another level. This would be a very loose arrangement where you can come and go to fit in with your own regime. You can cut your red coat according to your cloth. You’ll feel a great deal of satisfaction as you boost their fluency and help them get into the swing of things. It would mean so much to them. You’ll forge enduring friendships which will hold you in good stead when you travel the new neighbourhood. You can build your linguistic repertoire into the bargain. Even a smattering of other languages will take you far. I’m studying Bahasa Indonesian myself with the aim of mastery, but even when I can only greet people in their language, they are so impressed.’

‘It’s really speaking in diverse tongues’.

‘It is, Allan. Kismet lies with our northern neighbours, Allan. Let’s shape it together’.

‘That suits me down to the ground.’ I replied. I didn’t need to be asked twice. I want to contribute to strengthening English as the ‘lingua franca’ in the region. So, people will learn it because they love it, not because they are pressured to do so. I hope to travel there soon.’

‘Spoken like a real Mr. Red Coat’, said David. ‘Together we’ll help shape the way in which our neighbours view Australia’s accomplishments and our way of life. Now have you had enough to eat?’

‘You might say I’ve had eloquent sufficiency.’

We thanked the waitress Charmaine for her service and her chow mien.

Shadowing David, I helped him spread the words. I helped his charges expand their vocabulary, improve their pronunciation and words to pass their lips with a more natural rhythm and pausing.

They asked me about my own, ‘Mr. Red Coat, do you speak Chinese?’

‘I don’t speak it but I try to. I’ve got to be saying something.’

‘Would you help us if we get stuck trying to say the right thing.’

‘Anytime you’ve got a linguistic problem reach out to me.’

In this process I was gratified to observe first hand the quiet achievement of David, this bounteous unsung educator, to see the gains accruing to those he instructed come before they knew it .

Milk, Honey and More.

“Variety is the spice of life”, said David, recalling the famous proverb penned by William Cowper, the English poet. David’s dialogue was peppered with literary quotes as liberally as the gastronomic concoctions that came his way. “Life is so much more exciting when we try different experiences. It can make for a magical quality when you make a special blend of components that by themselves are no great shakes. Take these ingredients”, he said, pointing to some of the commonplace items on the dining table in front of us. “Potatoes, tomatoes, peanuts” he said, “all introduced to the West from the New World and now things we take for granted. Chips for our fish, tomatoes for our salad, peanut butter for our bread.’

‘Matches grown on earth but made in heaven,’ said Russel Ward the historian who was sharing our company.

Looking like a retired colonel, Russel sported a neatly clipped military style soup strainer, leather patches on the elbows of his tweed jacket, and a cravat.

The hunched back of the scholar may be considered a trait contradictory to the ramrod soldierly disposition but Russel bore no suggestion of scholar’s droop. His nose slanted downward from right to left at an angle of about ten degrees from the perpendicular, the result David told me later of a body surfing mishap.

‘The greatest marriages took place in Asia where people adapted their dishes to whatever was going. You’ve tasted how scrumptious these humble tomatoes and potatoes become, garnished in their hands, and how peanut butter can be transformed,’ Russel said. Upon my word I had, having tasted how it can be enlivened with shrimp paste in gado gado. And rinsed down with a good cup of tea.

‘And tea is not just tea, I said. ‘I’ve now learned just by the smell of it whether it’s assam, lapsang or broken orange pekoe. Whether it’s from Kenya, India or Ceylon. The British Commonwealth runs like a river through this dining room.’

’Courtesy largely of the East India Company a monopolistic private company which preceded both Empire and Commonwealth.’

‘Come on, wealth!’ it’s explorers pointed and cried to each other when they came upon new territories’, said Russel. ‘The main actor in this tremendous globalisation of the world, the Company secured land from Indian rulers, formed alliances with local craftsmen and exported a wide range of highly profitable commodities back to Britain. It was really the model for the multinational company of today in terms of the management of long distance supply chains. It’s wealth rivalled that of the British state. They poured much of it into the pockets of their British shareholders.’

‘How did this tiny band of adventure capitalists and glory seekers manage to achieve this in such a bountiful, populous country.’

‘They secured land from Indian rulers, formed alliances with local craftsmen and exported a wide range of profitable commodities back to Britain.’

‘Virtually running the country, deposing rulers with it’s enormous private army and navy, these merchants traded in not only tea and spices but commodities such as cotton, salt, silk, dyes and opium.’

‘So these British businessmen were international drug pushers.’

‘Quite so. Their export to China enabled them to export hugely profitable consignments of tea to Britain.’

‘This wouldn’t have led to a happy ending obviously.’

‘Getting the Chinese hooked on opium led to two wars against them. It enabled the British gunboats to humiliate their military and gain control of the ports and interior trade, win favourable treaties and buy whatever they wanted primarily tea. Pumping such huge amounts of this drug led to massive addiction and health issues there.’

‘So, the deal was that the British drank tea out of porcelain while the Chinese smoked opium.’

Their business grew to account for half the world’s trade.

‘If they controlled so much trade why was it replaced?’

Because of what the British government saw as their mismanaged and greedy operations, it stepped in to protect ‘their’ valuable assets, too valuable to be left to the Company threatened by local rebellions.

They surpassed the most rapacious of modern multinationals in their exploitation.

‘That reminds me, I’m feeling rather voracious right now, ’ I said.

“You can work out your own formula for combining foods,” David said. I gave it a whirl, going for a soft approach, indulging my affection for the confection. David had told me to take those ingredients and I took him at his word. Helping myself from time to time to some of the copious amounts of peanut butter, honey and fresh creamy milk provided in the dining hall, I conveyed these discreetly and in a trice to Epsilon, a whisker away. Churning out the frothiest, crunchiest, thickest milkshakes to all and sundry.

The creamiest kind that Mia Wallace would thirst for.

With an old industrial strength machine from our store, in a time before domestic blenders were widespread. These cool refreshing thirst quenchers hit the spot, going down a real treat whether in soothing the palate of curry munchers or the battered bones of rugby crunchers.

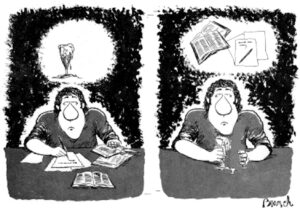

The very thought of indulging in one filled a student’s mind when doing assignments. The very thought of doing assignments filled a student’s mind when indulging in one.

I made a stir as a blend of resourcefulness, smoothness and conviviality.

In this rite of passage I crossed the Jordan River prehumously, getting more than my promised share of milk and honey. I was rewarded with the stick to your mouth palate pleasing power of the peanut.

The Milky Way

Taking a leaf from David’s book, I developed a discerning ear, picking up the idiosyncratic features of the various accents and ironing these out. A la Peter Sellers, I became particularly fascinated with Indian English, an exponent of which lived right next door to me in the residential tutors flat. Ashok Rathore was a perfectly fluent speaker of this juicy branch of our language, cut off from its trunk with a life of its own, important in its own right.

I worked on him not to ‘correct’ his speech patterns but to help him adjust them. For them to become more consonant with those of Standard English. For him to be aware of Indian grammatical peculiarities and what we consider archaisms. It being the practice of Indian speakers to substitute the ‘w’ sound for the ‘v’ sound, I primed this animal physiologist to pronounce ‘heart valves’ rather than what sound to us like ‘heart wows’. Thus obviating any bewilderment in his audience he could wow them with his linguistic clarity.

Our paths met one afternoon while walking down the eucalyptic hill to College. Our conversation touched upon a subject close to Ashok’s heart – the welfare of animals. Sighting a pair of kangaroos grazing contentedly a hop, step and jump away, unruffled by our presence, he remarked. “It is pleasing me so much to see our fellow creatures roaming free as nature demands”.

“It pleases me too”, I replied, supplying him with the present simple tense in place of the present continuous that Indians are wont to use. Fine tuning his solecistic speech without labouring the point, without disturbing the flow of this thought.

“It pleased the aborigines too, Ashok. They didn’t hunt them indiscriminately. They wanted to avoid an inordinate extent of hunting in certain areas. They understood that their existence was ultimately linked with the survival of their homelands plants, fauna and ecosystems.

“We have to pay closer attention on this balance ourselves now. We have to share the land with all things bright and beautiful, isn’t it?” he reasoned.

“We do, don’t we, Ashok” I replied, noting his curious Indian way with a prepositions and interrogatives. “When I was a kid I was knocked for a loop to come upon the rotting carcasses of these iconic marsupials, considered a pest, littering the ground after a spotlight shoot. I had gone on one such foray. Undone by their own curiosity, the great reds sat upright, silent, staring at the shooter’s trucks, as though waiting their pleasure. We have to pay closer attention to conserving them. The aboriginals were instructed not to hurt or take certain species until they had regenerated. They never wasted them but revered them as sacred”.

“As we are doing – whoops, I’m talking like this always – as we do with our cows” he pointed out.

“Indians have always exalted the status of cows” I chimed in, taking the opportunity to link his adverb with its verb. Having arrived at Epsilon, I invited Ashok to continue our talk. “You look as though you could do with a drink? We can discuss about this further over a cool milkshake.” I suggested, planting this deliberate boo boo to gauge his response.

“I won’t beat about the bush, Allan. That’s for kangaroos. We don’t need it here, so let’s just plain chew the cud,” he replied without hesitation, impressing me with his repartee.

“Hindu scriptures identify the cow as the mother of all civilization. It tills the fields, and its dung is essential as a source of fuel and fertilizer”, a point not lost on me having boosted the growth of my radishes and strawberries with its equine equivalent. “However, of paramount importance”, he stressed “is its role as a service of dairy products”.

“It’s one jump ahead of the kangaroo here, Ashok. Just how do you milk a boomer?”

“With extreme caution” he admonished, “their long claws are super sharp. Actually the kangaroo pouch is a mobile milk bar”. The milk, of varying fat and protein content, supplies joeys of different ages according to their individual specifications”.

“Milkshakes on tap, made to order”, I suggested. “What’s yours by the way” I asked him.

“Chocolate with malt. Twist my arms. Pile it in, if you get my weaning”, this fully grown hominid joshed.

“Both aborigines and Hindus view their sacred animal as sharing a common ancestor possessing profound wisdom’, I said. “Did you know that they share the same name for this omniscient being?” I asked.

“How’s that?” he enquired.

“Gu-roo”, I replied, keeping a straight face. “You’re pulling my legs”, he exclaimed.

“Just one”, I replied. “This is a standing joke. I don’t want it to fall flat”.

“Jokes apart”, Ashok ruminated, “Milk holds a central place in our rituals.”

“I think a toast is in order” I proposed “Raise your glass to our animal kith and kin. We sacrifice their lives to nourish and clothe us. We take their precious gifts to nature us. Let’s husband them wisely. Lest we kill the goose who laid the golden eggs,” I said, chinking the canister with my egg nog against Ashok’s.

The Rules of the Game

As of our being introduced Russel generously shared his knowledge of the world with me. He was a mine of information. I would often drop into his quarters unannounced just to natter about the wide range of subjects on my mind. He stimulated me and other young scholars to explore beyond accepted bounds, to question accepted interpretations, and to experiment.

One Saturday afternoon, I met up with him in the company of my English professor Herbert Piper in contrasting winter shades, beige scarf at a jaunty angle, watching Wright College butting heads.

This led to me thinking about those sportsmen spreading butts. One of those rugby players, an athletic jock from another college, famously treated women just like a football. He’d make a pass, play footsie, then drop them as soon as he’d scored.

As I wandered up, I overheard the Prof saying to Russel, ‘I honestly believe there is absolutely nothing like going to bed with a good book… or a friend who’s read one. Take Trollope’s novels. Harold Macmillan won’t go anywhere without one. I like a little Trollope in bed before I go to sleep.’

‘I’ll only take to bed what the parson allows.’

‘I didn’t think you were religious, Russel.’ Which parson is that?’

‘The one brought to mind by Nicholas Parsons.’

‘The English entertainment personality, adored by so many women?’

‘Right. Mine is the parson who likes knickerless women.’

‘Mine is the parson who brought a pair of knickers to the parish Christmas party.’

‘What has that got to do with Christmas?’ the bishop asked him?

“They’re Carol’s.’

‘Who’s Carol?’ asked the bishop.

‘She’s my mistress. What goes between a mister and a mattress.’

‘You know, like the fictional Leonora Vail in ‘The Astonished Heart’. She was mistress to it’s main character.’

‘And what’s that got to do with Christmas?’

‘The actor playing the main character is afraid of this time.’

‘Who is he then?’

‘Noel Coward.’

‘I’m sorry, am I disturbing your sporting conversation?’ I said. ‘I hope I’m not acting quietus interruptus.’

Professor Piper said to Russel, ‘Half a mo, I’m just going to get a few bacon and egg sandwiches. You can catch up with this young expanding man.’

‘Now Hercules be thy speed, Herbert. We don’t want them cold.’

‘Herbert and I were grown from the same soil. We go back a long way’, Russel said when the Prof had gone, ‘back to our varsity days in Adelaide.’

‘You would have followed Australian Rules football then, I guess.’

‘Rugby union was introduced to Herbert and I at university.

I drank pints with him at his dad’s pub after the rucks, mauls and lineouts. ‘Swallowed your whistle, Ref?’ he interrupted to catcall at what appeared the referee’s failure to call a clear violation of the rules.

‘Despite ten years of compulsory football practice, I was hopelessly bad at what you New South Welshmen call ‘aerial ping pong’-Australian Rules football. . I thought all football games were basically the same, that once you’ve seen one with players bunching up, you’ve seen a maul. I had no ball sense and no turn for speed-but rugby was quite another thing. It’s rougher and tougher.

Yet to draw crowds like those of Australian Rules, it’s always experimenting with novel ways to maintain the flow of play and minimise stoppages.

Sure, it was handy to run like landy, ’Russel said, referring to the Olympic runner, ‘but given enough brute strength, ignorance and willingness to do draughthorse work, one could do a useful job in the forward pack without ever necessarily even seeing the ball during the whole game.

That’s why I enjoyed it.’

‘It sounds like working in the N.S.W. Education Department’, I said.

‘Where teamwork, numbers and rough stuff are mixed, said Russel, ‘a lazy person can easily go unnoticed.’

‘I wish I’d said that.’

‘You will, one day.’

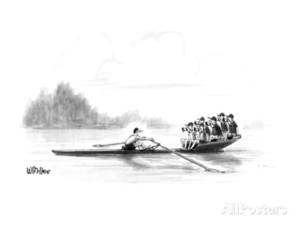

By then, Professor Piper had come back and hearing the tail-end of our conversation, said ‘Half a mo, surely rowing was easily the most enjoyable aspect of your undergraduate life.’

‘It’s the best team sport ever devised, albeit as you know, Herbert, a snobbish one.’

‘For a really posh one you’ve got to go to a school that’s got a river flowing through it. You can’t sit in the bath going, ‘It’s pretty good in the bath. The water’s got to be on the outside.’

Feathering the Blade

‘There’s special skills involved. Rowers don’t possess the nimbleness or quickness of the ball players hand, one that deceives the eye. But they do learn to control and co-ordinate the functioning of every muscle in their bodies with great precision.’

‘Steady from stroke to bow.’

‘What is more, they must make every movement of every muscle at the same instant as every other crew member, no more, no less. In every other game, a team member may excel by executing certain movements more brilliantly than others. In rowing any movement which differs by a hair’s breadth from that of others in the crew marks its perpetrator, not as a star performer but as a clown. There can never any such thing as a brilliant oarsman, better in some ways than his crew mates.

‘Moreover you don’t want to get the team makeup backwards: It’s got to be eight guys rowing and one guy yelling!’

‘All eight must row in harmony. There are only crews, units which may approach excellence precisely as each in proportion as each individual eliminates differences to become an integral part of a powerful, perfectly synchronised machine. All of which takes a great deal of time, sweat and sometimes a little blood on blistered bums. Moving as a single machine the eye of the beholder is never deceived by eight blades striking the water as one. Either they do or they don’t.

They also must acquire the stamina to go on hammering themselves mile after mile, forcing their minds and bodies to keep functioning up to and beyond the point of exhaustion.’

At which point Professor Piper announced ‘Half a mo, I’ve had a long week and I’m a bit done in too. I’ll be off now. Catch you later, Allan. Enjoy the rest of the game.’

After he departed, I said to Russel, ’ From what you say rowing should be promoted universally to train all the youth, not just those with the old school tie, to co-operate, work together and be seen as doing so’.

‘That’s an interesting thought to entertain, Allan, ‘he said, finishing his sandwich, and, taking a flask of whisky from his pocket, taking a short draught. ‘It would require a forward thinking government to subsidise it though. Would you like a swig, ’he said, offering me his flask.’ This drop’s thirty years old.’

‘Old enough to go out by itself. Incidentally, Russel, why doesn’t Professor Piper say ‘Half a moment’? Why does such a highly literary mind as him abbreviate it and come out with such slang as ‘Half a mo?’

‘ Half a Mo’s a nickname for me, ’he laughed, ‘to do with my erstwhile abbreviated moustache. Let me explain. I grew it as a fresher, possibly in a vain attempt to make myself look older, if not necessarily wiser than I was. When chosen to row three in the first eight, I was the only member of the team not clean shaven.’

‘I moustache you this. Was this clean cut aimed to cut down wind resistance?’

‘Not at all. Basing themselves on the well known fact that those who served in His Britannic Majesty’s ships had either to grow full beards or none at all, the rest of the crew conspired to regard my soup strainer as a provocative breach of rowing tradition. Just as there is honour among thieves, there is a certain levelling egalitarianism among snobs. Converging on me suddenly after practice one evening, they held me down and shaved off the right side only, confident that the resulting lop-sided cut of my jib would speedily force me to remove the other. Honour demanded however that I remain a figure of fun for the month or two it took for my facial hair to grow back into balance- and then that I retain ever after such a hard won, if intrinsically absurd, decoration. To this passion for levelling or conformity may be traced the continued existence of the moustache for the last decades.

‘One might say it has grown on you.’

High Hopes.The True Spirit of Learning

“Education should be an adventure, something that we undertake because it is interesting as well as instructive. Democracy cannot survive if decisions are to be made by the people and the people do not understand what they are asked to decide. To me the success of our scheme will be measured by the number of men who become more tolerant of the other man’s opinion.”

Robert Madgwick

I got clerical work in the external studies department preparing printed lecture and assignment material for distance students. As I was collating, stapling and bundling this one day we had a visit from the Vice Chancellor, Robert Madgwick.

‘Keep up the good work, folk. ’said this reserved, unruffled chief administrator. ‘Keep in mind the value of what we’re achieving. We’re meeting the intellectual and technical needs of our local region and those far beyond. We’re providing opportunities for people who cannot easily travel, often because they live in the shires, to attend lectures and obtain a university degree. We’re slowing that drift to the cities. People in New England have come to realise that the expertise and knowledge of our university can be used for the benefit of the surrounding area. Let’s not let them down.’

Close to Madgwick’s heart was the idea that people should have access to educational facilities over their lifetime. He saw this as a civilising force as well one bringing prosperity.

He was an influential proponent of ongoing adult learning in all it’s forms. He had been influenced by how the U.S. had created programs to help soldiers readjust to post war civilian life.

The university’s popular adult education courses were based on feedback from the local populace as to what they wanted to study. They boosted the prosperity of a wide area.

He promoted distance and extension studies in tertiary education and battled those academics who wanted formal studies kept in ivory towers. Traditionalists had rejected the idea of training and certifying schoolteachers by external studies and/or correspondence courses, stating that external degree or certification programs would be significantly inferior to residence education. They considered that they diluted academic standards and provided a sub-standard education Madgwick had enthusiastically supported it knowing that these objections could be overcome providing adequate standards were maintained in both the lectures and the subject matter. He knew that it would widen the base of support for UNE.

The program’s instructors also participated in internal education and had to be considered on a par with their internal colleagues. The examinations given to external students were the same as those given to internal attendees. External students were required to attend some residential courses as part of their degree programs.

‘What are you training to be?’ he asked me.

‘You might think this is a romantic wish but I’d like to join the diplomatic corps. I don’t know if I’ll make the grade as the selection process is very rigorous.

‘I might have to settle for becoming a teacher I guess.’

‘That’s a more sure bet and a great one. After my training as a schoolteacher I taught at Nowra and Parkes.’

‘How did you find that experience, Dr. Madgwick?

It was an invaluable one for me. It taught me that all young people are not equal either in ability or motivation, but that each one is a worthy object of the teacher’s endeavours. Each one is interesting in himself or herself and has a right to be helped to achieve their potential.’

As educators we have to to appeal to a community of people with many different backgrounds and goals.’

All That You Desire

Over coffee one evening in the Junior Common Room I gave David Evans my ear after asking him his recipe for attaining sophisticated taste. “Just as it is with different spices so too it is with our aesthetic appreciation”, David declared. “Learn to distinguish between the various products each bearing the special flavour of their agricultural belt, of a particular crop of writers and artists. Get to know their contents and their special ingredients. As for literature, read widely and as much as you can.’

‘Right on!’

‘Don’t worry about the categories, the constructs, whether you would agree with the writer or if you like the politics. Decide for yourself. Great writers are not to be bowed down before and worshipped, but embraced and befriended. Their names resound through history not because they had massive brows and thought deep incomprehensible thoughts, but because they open windows in the mind, they put their arms round you and show you things you always knew but never dared to believe. Appreciate the subtle variations. Reach out to find the ones that suit you. Keep in mind what I underlined before”, he mused, “Whether it be food we are talking about or fashion or books-the finer things- our tastes are often an acquired one. You’ll be amazed the kinds of things that grow on you once you get past their strange unfamiliar appearance and try them several times. Once you get past a certain threshold, trenchant insights and surpassing delights will flow in abundance.

Thenceforth too much of a good thing will be barely enough.

‘Good things come to he who waits.’

‘Yes, everything in good time. When it comes to taste, don’t act in haste. Work against the grain or you’ll never know what you missed. You may not end up taking to some, but at least you’ll have given them a go. Don’t give up on things easily. You’ll need to roll some new flavour around your mouth to see if you like it. Remember the proof of a pudding is in the eating.

At the same time be honest in your criticism. If something’s not to your taste don’t pretend otherwise. Whether it is or not, aim to justify your opinion, bringing to bear all your knowledge and discernment. You’ll become ever so cultivated in your tastes, widening your horizons, replete with your heart’s desire. Why then the worlds thine oyster, which thou with sword will open,” said David paraphrasing Pistol’s metaphor from ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’, ‘and suck out out to your heart’s delight,’ he added, winking.

Chaucer

It wasn’t long before I was sinking my teeth into some rich literary pudding. My plum assignment, analysing the work of the ‘father’ of modern English literature, the first author to use many common English words in his writings, was served up by none other than David himself “My task is to accompany you” he told our class “into medieval England and introduce you to a cross-section of its society – the world of the Canterbury Tales. More than five centuries and a huge landmass may separate you from this motley group of pilgrims swapping rattling yarns on their pilgrimage to Thomas Becket. But with Chaucer’s keen eye for how humans behave, these wayfarers’ tales are far from remote. Entry won’t be automatic mind you. For the journey you’ll be required to sharpen your language skills as were these pilgrims. Hard work will be the sole passport for admission. You’ll have to read Chaucer’s lapidary verse in the language of his day to uncover his gems– the hidden messages about the characters, the double-entendres, the bawdy jokes, the hilarious regional accents and the levity with which he undercut respected figures. The further you put your best foot forward, the more you learn this language, the more you will be rewarded. It will add an extra dimension to your experience. You’ll broaden your horizons of fourteenth century England and Early English literature – a seminal influence on our cultural development.

Henceforth our English class engaged Chaucer directly. We read aloud his masterpiece as he wrote it, pronouncing the words in the round rolling cadences of medieval English, discussing them keenly and writing about them.

David proved to be the perfect lodestar for this journey of discovery. Totally devoted to his subject matter, he knew it from top to toe. He had a contagious enthusiasm and handily made such difficult work fresh and exciting. With his clear silver tongue, he brought Chaucer’s characters to life. He brought clarity and even excitement in his own teaching. He obviously cared about his students and that they share his knowledge. Judging every individual with a single eye, he refused to move on in lectures until every student had a firm grasp of the content. He got such pleasure out of his work. The delight on his face with discussion briskly firing, even among students who were normally quiet, was plain to see. He illuminated everything we read with the same sharp eye as Chaucer himself. I could see more in the tales that I didn’t tumble to at first, especially with the context and background that he provided.

Each of us students chose one of the pilgrims to follow and study in depth. This meant giving some historical background that would elucidate the character’s tale for the rest of the class. In becoming invested in the Miller, I taught the class about The Peasant Revolt and the finer points of cuckoldry, bared buttocks, flatulence and a sadistic rear end attack.

Illuminated Texts

Chaucer’s early texts and others of the same ilk fanned another flame of David’s – his love of art. These handwritten books attracted my eyes in the first instance with their lavish illustrations – their addition of decorated initials, borders and miniature pictures, sometimes illuminated with gold, silver and brilliant colours.

“In the middle-ages these illustrated books were very popular, particularly those on the lives of saints such as Thomas Becket. These pictures were important as many of the people who looked at them could not read or write.” he explained.

“From what I gather reading in the papers and from my observations, many people still don’t read or write very well” I commented. “Why don’t we have beautifully illustrated books like these for all to learn from?”

“That’s a good question, Allan. The school authorities would argue that they don’t have the resources and that if they did they would most likely get vandalized. The way things are going with the spread of television, they’d probably say kids have got enough to look at. Its up to teachers to push for top drawer reading material in the schools. As for me I love drawing and painting in a variety of styles with the widest range of subject matter. That love is what I aimed to impart by example when I taught in high schools.”

“What are you working on at the moment, David?” I asked.

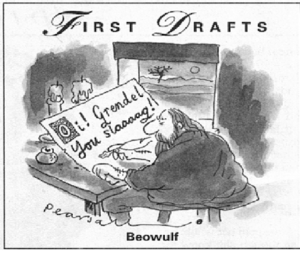

“I am working on illuminating manuscripts inspired by medieval art. My goal is to recreate the Old English epic Beowulf.”

‘The first draft is the hardest, I believe.’

He wanted to feel sure the art of illustrating manuscripts was safe.

‘This is an art that requires careful preparation, ‘he told me.

It’s one that would demand adaptability to technical change.

Men of Letters

More and more the aspiring intellectual, I plied David Evans with myriad questions about literature. I was set on my mind being as well stocked by reading as our shop had been with merchandise. “I want to be well read – not just well fed, David. How do I know which books stand the test?”

“Try this for size: Read widely, read wisely,” David adjured me earnestly picking up the theme we had touched on earlier “Tous les genres. Writers of substance. Take up their invites. Enter the settings they bring so vividly to mind. Meet the vast array of characters they give birth to and share their lives. Explore the ideas running through them. Look for connections. Follow the tales they spin moving us through delight and fascination. And when you read, don’t just consider what the authors thinks. Consider what you think Let them know what you think of their books. They welcome feedback – indeed rely on it to gauge their skill and shape whatever they’ve got in the pipeline. They ignore their readers’ thoughts at their peril. The same goes for the actors who bring the dramatist’s characters to life. They need to know how well they convey the spirit of the playwright. All in all the sky is the limit – so open your eyes, spread your wings and cover as much ground as you can”

“What do you see as great literature, David?” I enquired.

“The gist of great literature in all its diversity, when it all boils down to it, once we look past the particularities of place and time, is how it enriches our understanding of the human condition, what it tells us about ourselves,” he declared.

“Of course greatness is in the eye of the beholder” added David, “what a reader takes away from a particular work is a very individual thing depending on where he or she is coming from. We all relate differently in some way to the people, place and events we read about. As boys from the bush you and I probably relate more viscerally to accounts of the harsh realities of life on the land than some young city slickers. They in turn will be more familiar with the nitty gritty faster paced anonymity of city life. The crux of literary criticism and discussion is to seek out the very qualities that make for great literature and arrive at some common agreement about these.”

Passover and the Plotnicks

I waited on tables in the College for special occasions on the social calendar. This helped pay my way through. I got to know the various academics and caught snatches of their discourse. One who dropped in to dine on the high table was was Zelman Cowen, the new Vice-Chancellor. A former Fulbright scholar and significant expert on constitutional law, he was part of a global academic network.

His style was profoundly collegial. He believed that the ethos of a university must be that of an academic community, not a managerial unit. He worried that the focus on research could come at the expense of focus on students. He saw a key role of universities as preserving and transmitting a shared culture.

This spirit of sharing extended to the dinner function held to welcome him.

‘Gentlemen,’ said Alan Treloar, ‘I trust this hearty repast does not disappoint your refined palates as you share information about the latest developments in your respective fields.’

‘Pass me over the salt, please Dr. Ward’,’ Zelman requested Russel Ward

after my fellow waiters and I had laid out the various dishes..

‘Would you pass me over the salad dressing when you’re finished,’ Alan Treloar asked Professor Le Gay Brereton.

‘Pass the parsley over to Professor McClymont,’ Master Treloar asked Russel Ward. ‘I recall he sprinkles on heaps as a garnish.’

‘I feel right at home here,’ said Zelman. ‘We call a feast such as this Passover.’

‘These green grapes pair well with camembert,’ said Alan Treloar, spreading the soft, creamy cheese onto a cracker.

‘A lot of time has been spent in selective breeding to come up with this pleasing union. Scientists in rural science have been able to come up with the very best table grape cultivars. They tend to have large, seedless fruit with relatively thin skin.’

‘I imagine there must be many challenges to face in achieving such results,’ said Russel Ward.

‘Our work is at the forefront of the agricultural industry. We are ready to solve complex problems in agricultural systems across enterprises, landscapes and the globe.’

‘ I Hope you can fnd a solution to a problem came across recently,’ I said. ‘I had no sooner sunk my teeth into a nice jucy apple than I felt something wriggling against my tongue. It was a worm. I spat it out Ugh! Should I be concerned? ’

‘That’s the caterpillar of the the codling moth,’ said Professor Le Gay Brereton. ‘It lays its eggs at the base of newly formed apples. The caterpillars then hatch and work their way into the center of the newly formed apple often without detection, where they stay put until they mature and work their way out .’

Professor McClymont added, ‘We’re researching ways to control these pests without using pesticides. There’s nothing for you to worry about. Whilst unpleasant for humans, they’re harmless. You would only have digested some extra protein.’

‘What are some potential problems with potatoes ?’asked Russel, spearing a serve of the crispy potatoes from the tray of roasts.

‘We help potato growers to combat pests, disease, or deficiencies that could potentially ruin a harvest, ’said Professor McClymont . ‘That way they can expect a bumper crop.’

‘What improvements have been made in the production of corn?’asked Alan Treloar as he helped himself to a cob of it from the tray.

‘Advancements in corn research have led to firmer, resilient types with more desirable characteristics,’ said Professor McClymont.

They certainly go well with green beans,’ said Alan Treloar.

‘We’re working on ways to increase the size of corn kernels as well as their length and number in rows.

‘Corn is a very versatile product, isn’t it,’ I put it to the professor.

‘It was used during World War II for all kinds of military industrial purposes.

It was used to produce ethyl alcohol that would be made into synthetic rubber to replace imported natural rubber supplies cut off. The tyres of many vehicles that rolled across Europe in 1944 were made from synthetic rubber that “grew” in Nebraska cornfields.’

‘That’s amaizeing,’ I commented.

‘Where does Agricultural Economics fit in with solving those complex problems you talk of, Bill ?’ asked Russel.

‘Our sister science deals with how producers, consumers, and societies use scarce resources in the production, marketing, and consumption of food and fibre products. The farm-to-table approach emphasizes the use of locally sourced ingredients, typically through direct acquisition from the producer. This direct approach ensures fresher, more nutritious, and more sustainable products.

Of course with some products involving more distant transport the acquisition is less direct.

Curses Are Forever

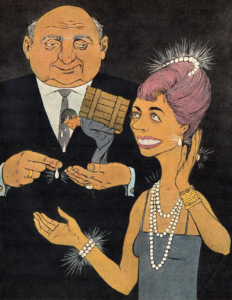

I was aware of Professor Cowan’s keen interest in the immigrant and specifically Jewish experience. He liked to tell droll jokes. The whole megillah. His favourite involved a certain Mrs Plotnick whose husband was the hard-driving boss of a business company. From the sweat of his employees’ brows he came up with diamonds for her.

. ‘This is a classic one’, he told his auditors. ‘ A younger woman says to Mrs. Plotnick at a dinner party, ‘that is the most enormous beautiful diamond necklace I have ever seen’.

Mrs. Plotnick woman answers, ‘You don’t want this necklace, do you?’

The younger woman says, ‘Why not?’

The older woman replies, ‘because it comes with a curse.’

‘ A curse?’

‘Yes, it can bring you misfortune.’

‘What kind of bad luck does it bring?’ the younger woman says.

‘It’s called the Plotnick curse,’

‘The Plotnick Curse? That sounds horrible, what is it?”

The older woman says, ‘Mr. Plotnick.’

Quick on the uptake, bold as the brass tableware I had laid for him, I said ‘Mazel tov, Professor, is anything all right?’

I had heard he liked to have a bit of a laugh at his own expense and didn’t take himself too seriously. Here I was referring to the stereotype that Jewish people gripe a lot.

‘Young man, I assure you everything is fine. The victuals have been cooked well. My seat is comfy and the temperature’s perfect.’

Professor, I hope I’m not out of turn, but I couldn’t help overhearing your joke and have reached this conclusion. Many a necklace becomes a noose. Is that Moses Plotnick, the restaurateur you’re talking about?

‘Moses Plotnick? Never heard of him,’ said Zelman. ‘Who is he?’

‘He runs an establishment in Chinatown, ’I said, decanting his wine. ‘Moses Plotnick’s Chinese Restaurant.’

“My goodness, how did a Yiddish boy get into that line of business?”

‘Therein lies the joke,’ I said, full of chutzpah. ‘I asked Moses about this when I ate in his licensed restaurant. This was his explanation: ‘After I arrived in Sydney in 1949, having escaped the probrems back home, I had to report to the Department Of Immigration. I was reery worried that I would be rejected. I knew they didn’t let vewy many of my countrymen in.’

‘Why didn’t you stay in China. You’re enterprising, successful and would have done well wherever you settled. Don’t you miss your country?

‘Ret me answer by telling you a story. Once upon a time there were two Chinese. Now rook how many there are. More than half a billion people.

‘Half a billion. That means even if you’re a one in a million kind of person, there are still many hundreds of others exactly rike you.’

‘Apparently, one in six people in the world are Chinese’, said Zelman. And there are six others in my family, so it must be one of them. It’s either my wife, Anna or my son, Ben. Or my next sons, Shimon and Yosef or my daughter Kate. Or my youngest son, Ho-Chan-Chu. But I think it’s Shimon.’

‘Did you hear about the rook-a-rike competition in China?’ Moses asked me.’

‘No I haven’t,’ I replied as I tried to chew my first ever fortune cookie, ‘Who was the lucky winner?’

‘Everybody won.’

‘It’s probably best to be a little bit different but not too much.’

‘Anyway,’ Moses continued, ‘I was anxious to be just a bit unusual in a good way here Down Under, to stand out from the crowd, to risten and to rearn. So while I was waiting on the queue at the Department, I overheard the officials ask the Englishman three places ahead of me, ‘Do you have any felony convictions?’

The man replied, ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t realize that was still a requirement.’

They then asked the man two in front of me on the line, ‘What is your name?’ he replied, ‘Shayn fergessen,” which in Yiddish means “I’ve already forgotten.” When we eventually finished being processed the man told me outside the official recorded his name as Sean Ferguson.

They then asked the man in front of me his name.

‘Moses Plotnik’ he replied.

When my turn came to answer the same question, I replied ‘Sam Ting’.

After I managed to swallow my dessert, Moses asked me, ‘Did you enjoy the cookie? I hope it predicted good luck for you.’

‘I don’t know about that. To be honest it tasted rather papery.’

‘You’ve got to take the message out. Ret me order you a drink to help it go down. Nodding his head to the barman, he called out to him what I took to be ‘One gin sling!’

‘No thanks ,Moses, I’d prefer a beer.’

‘Ret me point out something, Sir, Wun Jin Sling is our barman.’

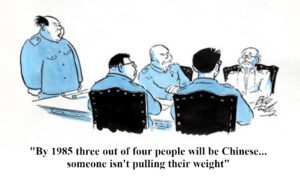

On a more serious note, I heard Zelman on another occasion talking to Russel Ward. They were discussing the incident sparking off the Chinese cultural revolution.

‘It was all given impetus to midway last year’, said Zelman. ‘A big character poster went up at Peking University lambasting the university president, Lu Ping. It took on a momentum of its own.’

‘His role must be mostly the same as yours.’

‘Quite true except on a much bigger scale. He was accused of suppressing political debate. Mao announced his support for the critics and, using his prestige, called on millions of students at secondary schools, institutes and universities to join the Red Guards to ferret out other ‘reactionaries’. This is outrageous. Can you imagine our Prime Minister butting in to support that here?’

‘This is true, Zelman. But let’s not be naïve. Our dear leader may not come out openly and be so one-sided, but he can, I assure you be a big influence behind the curtain.’

‘You’re talking about Robert Menzies,’

‘The Kings Counsel. The youngest one in Victoria. A big influence on you, Zelman?’

‘Certainly on my mother, so ambitious for me. She wanted me likewise to achieve so much in the law, she called me KC.

Interpreting this as ‘Casey’, Russel said, ‘She chose this so that you sounded more gentile? ’

Actually it was my father who changed our surname from Cohen for that very reason.’

‘It hasn’t been uncommon for jewish people to anglicize their names, has it,’ said Russel.

‘It could lead to episodes of confusion. There were two partners in a Melbourne legal practice named after them, ‘Lipschitz and Aarons’. One day Lipschitz said, ‘We’ve got to change our image. I don’t want to have such an stigmatised name. I want it to sound more Australian. I’m changing my name by deed poll to Churchill. Aarons looked at him and says, I like that idea. I’m going to do the same thing. I’ll be Churchill too. We’ll be known henceforth as ‘Churchill and Churchill’. They shook on it with satisfaction and got a new brass plate on their door and new business cards.

The first day under their new name they’re in their office and the phone rings. Their receptionist picks it up and says, ‘Churchill and Churchill’. The two partners look at each other proudly until she asks the caller, Which Churchill do you want, Lipschitz or Aarons?’

‘You kept your first name, Zelman.’

‘You can take away the strange letters, the Zs and two As. You can change Cohen to Cowen. But you can never take away the Jewishness. A Rosenberg by any other name remains the same. I take great pride in my first name. I’ve been very successful in spite of it. I’m no token. I’ve progressed I believe on the basis of my merit. I realised very early it was possible to get to the top… if I worked hard. With a little bit of luck for good measure.’