The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose off the common

But leaves the greater villain

Who steals the common from the goose.

The law demands that we atone

When we take things we do not own

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who takes things that are yours and mine.

The poor and wretched don’t escape

If they conspire the law to break;

This must be so but they endure

Those who conspire to make the law.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

And geese will still a common lack

Till they go and steal it back.

A 17th-century rhyme that stands the test of time.

It was far from the ‘you’ve never had it so good’ scenario that Harold Macmillan spoke of, referring to post war prosperity. In January 1972 a good number were still on the breadline and the unions were at loggerheads with the government. The old image of class warfare which had been laid low the previous decade now reasserted itself. There was a nationwide miners strike.

During the state of emergency brought in to deal with the dispute Britain was plunged into darkness and holdups.

I was having to move around my flat by candlelight and torchlight, wrapping myself in blankets and duvets to keep warm and boiling water to wash in. I wore heavy coats and fingerless gloves constantly to guard against the cold.

The children at my school were well rugged up to counter the chill and insulate body heat with three layers of clothing.

I went into a lamplit general store in Notting Hill to buy some sources of lighting as electricity supplies had ran low.

‘Can I help you?’ asked the storekeeper, using a head torch to keep trading.

‘You could start by cleaning your teeth’ I felt like saying, noting their stains and, moving further away, his bad breath, but said instead, ‘I’d like to buy some candles.’

‘ What did us British use before candles?’ he asked me before supplying the answer himself. ‘Electricity’.

‘Miners and power workers are holding the nation to ransom, ’he continued. ‘Never has respect for established law and order been so disdained. The government has sold out to the unions. It’s anarchy, that’s what it is, ’he whinged . ‘They’ve had it so good. They might be willing to do an honest day’s work. The trouble is they want a week’s pay for it. They think running a business is a crime. That a businessman’s capital comes effortlessly. Where do you think this all came from?’ he asked, waving his arms to his well stocked shelves.’

‘From the back of a lorry?’ I said not leaving it at that.

The next time I went into his store I said to him, ‘ Morning. Is anything all right?’

‘The economy’s gone down the drain. It’s happening all over the shop. Now the storemen and packers are threatening to withdraw their labour.’

‘If you see these workers as hostage takers, why aren’t you taking a page from their book. Why aren’t you out picketing them yourself.’ I asked.

‘I’m against picketing, but I don’t know how to show it.’

‘You must give up easily?’

‘I did try writing an open letter to the miners’ leader but I couldn’t send it .’

‘Go on , say it. You couldn’t fit it inside the envelope.’

In spite of this crisis many doors were opening for me.

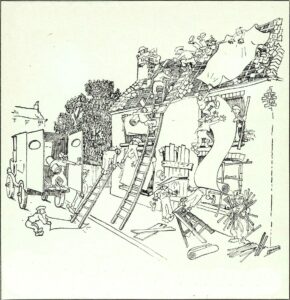

After checking nobody behind was them, me and my mates went round the back, scampered up drainpipes or trees to the first floor where necessary and opened the windows. These were in all conceivable types of empty properties from luxury flats to leaking dustbins, from abandoned schools, such as Paddington Lower Secondary where I had taught, to disused factories and theatres.

When everybody was trying to sleep, we were somewhere making our midnight creep until the rooster crow.

Some felt envy when they missed out on what turned out to be a good prospect. Many people know a good thing the moment someone else sees it first.

We picked locks and disconnected any constraining chains with our bolt cutters.

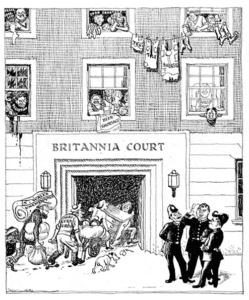

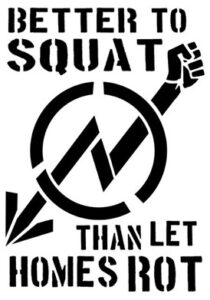

The guardians of the upper end of the property market looked unkindly on our backdoor bids for socially upward mobility. After a tip off, our occupation of an empty 25 room hotel like building in a quiet, quite expensive area was immediately emulated by that of the blue meanies. In the lock up Piers Corbyn, prime mover of squatter’s resistance, received a lecture from a Chief Inspector: ‘Squatting is one thing, you have to live somewhere, but squatting in Maida Vale is another. Stick to your own patch!’

It was in everyone’s best interest if you looked for a building that’s genuinely empty and out of use, and has been for as long a period as possible, because that’s more likely to last longer for and because very few people actually want to deprive people of homes or potential homes or their livelihoods.

Often the buildings we took over were ones from which the occupants had just been evicted. In a game of musical houses, they moved back into them straight away. We selected empty ones that had been out of use for as long as possible. These were likely to last longer because you were less likely to be discovered. We didn’t want to deprive anyone of their potential home or their livelihood.

In one regrettable case a homeless man mistakenly and briefly passed through an occupied apartment. It was in an block where most tenants had been moved out. Except notably one couple who kept mostly to themselves. The wife was agoraphobic. Her husband worked the night shift in the newspaper industry and went drinking afterwards. He came home to find the wannabee squatter exiting in embarrassment.

The husband went to Harrow Road cop shop later in the afternoon. He had been informed the squatter was apprehended and was spending the night in a cell.

‘I want to speak to the man who broke into my house last night’, he told the desk sergeant .

‘What’s the rush?’ the sergeant told him, ‘You’ll get your chance in court, ‘

‘I have to know how he got into the house without waking my wife, ‘ he pleaded, ‘I’ve been trying to do that for years.’

Before he was released the squatter, eager to leave, was given a strong warning from one of the Harrow Road Runners: Half a tick Mister. Before you go remember this. You can’t go walking into someone’s residence poking about their personal possessions, disturbing their privacy. That’s for the police.’

The uninhabited houses and buildings we cracked now became homes and social centres. At first our members had no services. No water, light or gas, no cooker, fridge, telephone or television. Just naked pipes and wiring. In some cases we had to dig in a connection to the main water supply.

You never knew what you were going to find in the unlit gloom. Might there be a dead body? Or a horde of giant mutant rats? Hidden drugs stashes, or money, evidence of occult ceremonies. Of course, there was never any of that, just a lonely sense of emptiness and neglect.

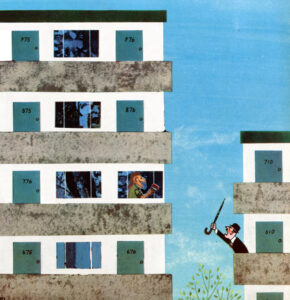

One family moved into the top floor of a long abandoned high rise soulless block of council units. The father said, We’ve got to do something. We’re afraid to look down.’

‘Because of the height?’ I asked.

No, because of the cockroaches.’

When rats visited, their whiskers bent. They scuttled away.

With any mucky places we went to work cleaning the bare floorboards of the detritus of months and years of neglect; sweeping up such things as pigeon skeletons, strewn masonry and bits of broken furniture. On first surveying the scene, I thought to myself, ‘I’ve had nightmares that look like this.’

Undeterred we patched the damage caused by vandals and thieves, hoovering up the dust of ages, caulking up holes in the walls, disinfecting the tang of mildew and urine .

It was said one house proud member wanting to clean up his boarded-up windows, went around round them with a sander.

We connected the gas and the water to the mains by bypassing the meters. We clamped industrial magnets to the ancient electricity meters to slow down their mechanical parts. We used the halogen street lights as a source of power.

We reconnected the telephone systems. For showering purposes, some devised their own Heath Robinson-like contraptions with lots of pipes.

Then to win over the neighbours. It’s crucial to take account of their feelings.

When squatters move into a street, they are observed in a way that few ‘legitimate’ occupiers experience. Their every actions such as building extensions are carefully noted.

They are inevitably commented upon.

It didn’t make it easy when some looked about as ‘local’ as a pride of peacocks.

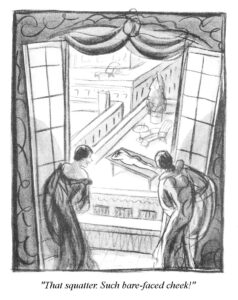

At the sight of the more exotic, the eyes of the local population opened wider and wider and then narrowed to unappreciative slits. Their patina of being different screamed ‘outsider’. There were plenty of people who believed we squatted simply to avoid what they saw as ‘mans inevitable lot’, namely the paying of rent and that we shouldn’t get away with such cheek.

If they were getting ripped off for living in some fancy box, it was only fair that others should too.

‘Get a haircut, a well paid job and buy a house like me,’ shouted one homeowner to the man squatting in the building across the way from him.

‘You don’t know what you’re talking about, ’the squatter called back, his girlfriend nodding in agreement. There was more to the situation than met the eye. She was in the bath which happened to be in the kitchen, turning the taps on and off with her toes, chatting to him while he painted the wall.

‘It’s not your place to tell me that. There’s plenty of great low rental properties if you take the trouble to look.’

‘You don’t see the whole picture. It looks very different to that from where I’m standing. Let me take you by the hand and lead you through the streets of London’, sang the squatter through his window, ‘I’ll show you something to make you change your mind.’

‘ I doubt it very much if my own soft hearted wife can’t. She donates money to the homeless and I donate money to the topless.’

There was nothing the squatter could do to convince the mortgagee. They were arguing of course from different premises.

Some owners rejected any request to extend any squatter an electrical extension cord even if the squatter offered to cover the costs.

Then there were others who had been having battles with their landlords for years over repairs and were glad to see us standing up to them. Others welcomed our members with arms outstretched as we reanimated rotting structural corpses with homely repairs.

Squatters walk a knife-edge between acceptance and hostility.

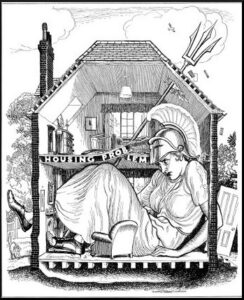

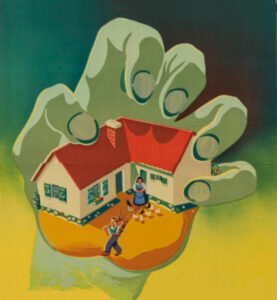

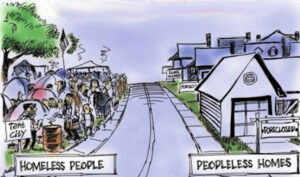

The epicentre of this housing conflict arose from the clash of two opposing ideals. The right to shelter and the right to absolute property ownership are in constant conflict. It is difficult to reconcile the obligation of the community to protect the homeless with an individual’s claim on their personal possessions.

‘This conflict seemingly ebbs and flows from what I can see, Piers.’

‘It boomed after each of this century’s two world wars, when returning soldiers and their families needed places to live. The end of the First World War in 1918 created a huge demand for working-class housing in towns throughout Britain.

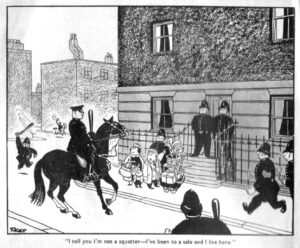

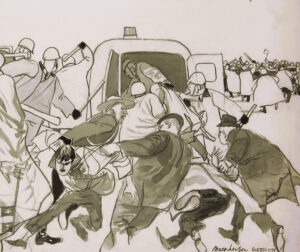

These squatters being led way by police officers were arrested during a forced eviction in Dagenham in 1932.

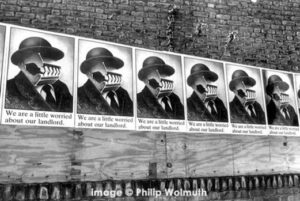

Tenants united to bring down those landlords taking advantage of the housing shortage.

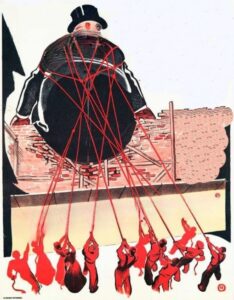

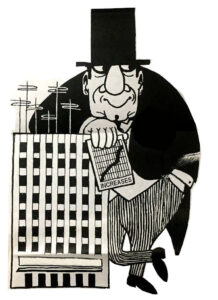

They saw them as unscrupulous, greedy and overbearing, more interested in property as an investment, rather than people’s home. Landlords who mistreat tenants by being intrusive, who overcharge, neglect maintenance and ignore phone calls.

After World War 2 the housing market was very tight.

During the War people set about repairing and occupying abandoned houses that had been damaged by the bombing.

At the end of the War there were thousands of badly housed families and those whose homes had been destroyed.

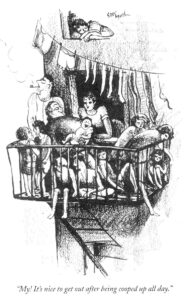

They moved into all sorts of buildings – from redundant service camps to hotels and luxury flats in central London. Overcrowding was rife.

Some did this out of necessity, others in protest against housing and other shortages.’

‘What happened to this movement?’

‘It was stamped out in 1946. It didn’t take long for our rulers to forget that wartime spirit of national unity they had promulgated. This vanished as those seeking shelter were evicted from properties they occupied.

‘And now it’s picked up steam again.’

‘It’s a barometer of the times.’

‘In one of the richest countries in the world, people still have to resort to such desperate actions. What’s brought this about again?’

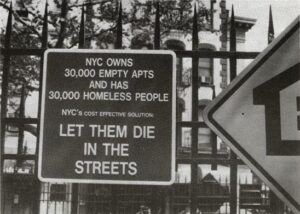

‘The housing shortage has become a permanent and chronic feature of British society.

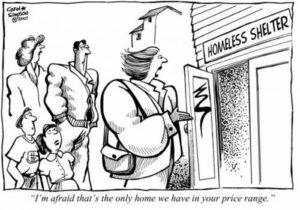

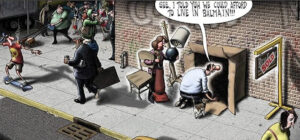

‘The current version is down to the emerging property boom we’re going through. House prices have soared, especially in the newly desirable parts of major towns and cities. The average price of houses has almost doubled in three years. As well as making it difficult for people to buy their own homes, the boom has made it extremely profitable for landlords to evict tenants and sell property. In many areas low income tenants are being pushed out their homes.’

‘What is government doing to protect the tenants?’

‘Their priority is to protect the owner rather than the dweller. The houses are often improved with the aid of government grants before being sold off to wealthier newcomers. Property companies also buy rented properties to demolish or refurbish for luxury homes, second homes, short lets as well as offices.

’‘And Council politicians facilitate this?’

’One councillor I know boasted, ‘ I can do so much for this place at grass roots. You know, high rise, tower blocks, malls .’

‘So property from densely populated relatively cheap flats are upgraded to owner occupied or more expensive accommodation.’

‘It’s all very calculated.

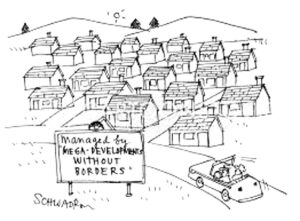

This leads to a decline in the rental sector and exclusion of lower income groups, singles and childless couples from affordable housing. And to the rise of New Men. New Men hacking out new fortunes. Altering the urban landscape through creating greater social division.’

‘Gentrification is just the fin above the water, ’said Piers. ‘Below is the rest of the shark: a new American economy in which most of us will be poorer, a few will be far richer, and everything will be faster, more homogenous and more controlled or controllable. We’re moving to a situation where there will be no land in Britain that is not owned by someone to the exclusion of others.’

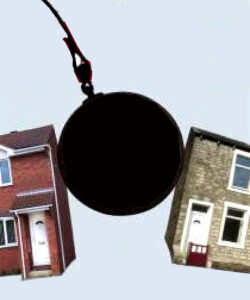

This picture became familiar. A property company intent on finagling planning permission to redevelop would buy up houses in an area leaving them obscenely empty when possible.

‘With land values steadily rising, ’said Piers, ‘the speculators buy property as an investment with no intention of using it. These land bankers withhold valuable land from use and deplete the nation’s housing supply. This is a scourge.’

‘You’ve just got to look around to see that’, I said as we gazed on a swathe of empty houses.

‘This damage precipitates the undermining of the community’s lifeblood. The spiral of decline leads to a fall in equity, vandalism and the collapse of local businesses. Residents lose heart and the will to fight. Those that can move out of their own accord and the neighbourhood deteriorates still further.’

‘And not every one of them is seen as deserving of housing assistance, are they?’

‘For those people who fall between the twin stools of home ownership and council housing, who would be traditionally housed in the private sector, opportunities are shrinking, rents rocketing and security diminishing. The dream of the older generation to pay off a mortgage is going to disappear like the darkness at dawn for many. As one wishful home owner who refuses to accept this reality tells me, ‘ I admit that I live in the past, but only because housing is so much cheaper.’

‘In that situation, at least some prospect of future security is held out. At least it appears on the surface the system cares.’

‘In what way?’

‘If you think no one cares if you’re alive, try missing a couple of loan repayments.’

‘Now the dream of young families is to get a mortgage.’

A generation is being locked out of home ownership.

‘I turn fifty next week’, said one of our local supportive tenants, ‘bearing the distinction of being a ‘no home buyer’. I don’t own property, never have and wonder if I ever will. In my street, a duff two-bedroom pied-à-terre with no view, no balcony, and a burgeoning case of concrete cancer will set you back a king’s ransom.

Me living here is largely been a lifestyle decision because to be in the bullish market for property around here you need to be an investor, Lord McAlpine, or an arms dealer, so I pay a boatload of rent instead of buying in more ‘affordable’ suburbs.

It’s fantastic if you’re one of those three groups and all you have to do is roll over in your hammock on the Costa Brava and count the pounds pour through the bank account. For the rest of us living on the Costa Packet, it’s not so great but it’s a situation we’re coming to terms with. We simply have no alternative, save moving to suburbs far away from friends, family and, often times, neighbours with teeth.

The thing that rankles, however, is the ‘golly, gosh, nothing we can do about it’ attitude spouted by different governments which is patent balderdash. Property is fast becoming an engine of wealth creation for investors. Its ballooning unaffordability is being encouraged, maintained and protected by governments led by both parties. While political parties profess to care about first-home buyers, the reality is they prefer to garner the votes of the owner-households that want policies that would increase house values’.

‘We have to distinguish between income that is ‘earned’, ’continued Piers, ‘and the economic surplus that disproportionately flows to those that “love to reap where they never sowed. The ordinary progress of a society which increases in wealth at all times tends to augment the incomes of landlords and ‘developers’.

‘They’re the ones who are sitting pretty.’

‘They have ‘lots’ to be thankful for. It gives them both a greater amount and a greater proportion of the wealth of the community, independently of any trouble or outlay incurred by themselves. They grow richer, as it were in their sleep, without working, risking, or economizing.

‘They’re as popular as piles, aren’t they, Piers.’ I remember this comment as I was being guided through Nottingham Castle:

‘This section,’ the guide informed us, “is hundreds of years old. Not a stone in it has been touched, nothing altered, nothing replaced in all those years.’

‘Well,’ said one one of my fellow visitors dryly, ‘they must have the same landlord I have.’

‘Property investment as a means of ‘creating wealth’, increasingly common in most western nations, sits at the root of many of our economic and social problems. That’s the case today and has been over many years as urbanisation pushed into the countryside.

It has both a debilitating and destabilising effect on the economy. This is evidenced clearly in a painful and rising trend of income and housing inequality that burdens the capacity of the ‘welfare state’ to compensate.’

‘The rentier class argues this incapacity develops because people are being given too much. They say there’s no such thing as a free lunch.’

‘That’s very true. They leave it to others to pick up the bill.’

‘If you live in London, the chain of injustice choking the world starts with your home. It’s what you have to continually have to worry about hanging on to.’

‘It’s them we have to worry about. Those who profit from such waste and worry.’

‘Unless profits from the ‘enclosure of the commons’ – land, water rights, minerals, and so forth – are effectively collected and shared for the benefit of the community, all productive gains, every improvement in society and the economy, will be capitalised into rising locational land values, enriching those that own the assets but more so, those who created the credit and trade on the debt. For them this is nature’s free lunch.’

‘London should belong to the millions, not to the millionaires, ’I said.

‘ Real estate speculation is rewarded over and above productive enterprise. It’s profiteers should have to pay for these gains.’

‘The government should collect society’s economic rents in lieu of taxes that impede productive labour and industry, including taxes on the improvement and the transfer of property. As Thomas Paine observed “Men did not make the earth…. It is the value of the improvement only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property. Every proprietor owes to the community a ground rent for the land, which he holds.’

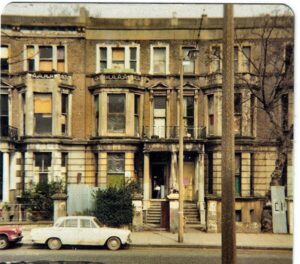

Along with the existence of many empty properties, remaining empty for long periods, there was a lack of adequate public housing. So the most tempting squatting sites were entire streets, sometimes entire neighbourhoods, which had been earmarked for slum clearance and redevelopment and which were left empty while the local authority and its planners got their act together. The increasing desperation of of people at the bottom end of the housing market, together with the growing number of empty houses, led to the growth of squatting . It led to the renewed fight for decent housing for all.’

‘All squatting is inherently political when I comes down to it, don’t you think, Piers?’

‘Property equals power, and squatting has been historically linked with the struggle of the dispossessed, anti-establishment movements, and the control of space. The appropriation of space as a protest tactic is part of a long-term strategy for solving the housing crisis. The practice is as old as the notion of property itself.’

‘Do any particular periods and people in English history stand out for you in this respect, Piers?’

‘Of great influence in the political context was Gerrard Winstanley and his Diggers.

They provoked a wave of short lived Christian communes in the 1640s. Winstanley questioned the very foundations of property ownership, and the class structure that resulted from it.’

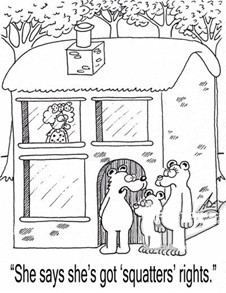

‘What rights do squatters have now and how far back do they go?’

‘The origins of ‘squatters’ rights’ lie in the ancient, unwritten law that if you could erect a dwelling overnight on a piece of land, it had the right to stay there. Similar laws can be found around the world.’

‘Where does the law stand on this? Does it see this as a criminal offence?’

‘Squatting has always been regarded as, at worst, a civil offence: squatters were first protected against heavy-handed eviction by the Forcible Entry Act of 1381.’

After people took up a squat in mid seventies Angry Anglia, the procedure was that if landlords wished to evict squatters from their property, they had to have them served with a summons. Plaintiff and defendant then attended court, and if, as happened in the large majority of cases, the court found in favour of the landlord, the squatters would be evicted. This could happen within days or months, depending on the bailiffs’ waiting list.

We occupied GLC buildings to stop yet more council housing being renovated for a fewer number or sold off to private developers.

The Greater London Council had a waiting list with thousands of people in need of quality, secure, and truly affordable housing that the peeling, flaking houses on Elgin Avenue and elsewhere once were. In the face of such housing need in London and the whole of the UK, sales of council housing was madness. The attempted sale of such housing was a part of the social cleansing that was happening across the land where local working class residents were being forced out so that wealthier people could buy them up.

This growth in squatting, both in scope and scale led to us raising questions not just about the amount of housing available but the very nature of housing and the quality of community life. This movement was the avatar of all that the social movements of the 1960’s and 1970’s were said to be. It became a means through which to challenge cultural norms and develop alternatives: by challenging traditional housing allocation systems, redefining housing from a purely functional to a fertile cultural space, redefining traditional concepts of the legitimate ‘household unit’; by working co-operatively; and by the self-provision of housing, a basic material resource.

Where houses couldn’t be divided into self contained flats, people had to learn to live communally. This acted to counter the adverse effects of individuals living alone- neurosis, their jobs, alienation, atomization, which can in extreme cases lead to psychosis and general personality breakdown. Every single human right we enjoy today has been won by people focusing outward not inwards.

We occupied one boarded up hotel which had been designed to squeeze in as many occupants as possible. We took advantage of this ourselves.

The resulting social mix contrasted with the desert-like council developments where the inhabitants are socially homogeneous. It gave people a sense of identity. They had a sense of living somewhere special.

The original residents of some of the high rise council blocks who had escaped the damp terrace houses looked down quizzically on where they had left. We had organic gardens. They were eighteen stories up in a broken lift looking down on their old homes.

On Elgin Avenue there was undoubted squalor -but it wasn’t general, seedy, or demeaning.

It looked like the cover of Led Zeppelin’s album, ‘Physical Graffiti’.

Unlike the GLC whose plans were ‘delayed’, we brought our own forward. As a counterweight to the nation’s gloom, there was an ongoing campaign to muck in and help out repairing and maintaining things.

Skills such as wiring or plumbing had to be self-taught and shared with people less able to do it. We embraced a belief in the principles of self help. We facilitated craft and print workshops, alongside practical enterprises like crèches and food co-ops. We made do and mended things. Pooling our supplies of tools and materials, people used ingenuity and inventiveness to make the better homes very habitable.

The lifestyle decision to squat conflated art and the everyday by circumventing the establishment. Adapting buildings to their needs, an ability normally restricted to wealthy owner occupiers, some uninvited guests went far beyond being able to choose their own paint, curtains and wallpaper.

They made light work of decorating the rooms with a shabby chic sensibility all of their own. This was a way to illustrate their flair for interior décor.

’What do you think about my walls?’ one decorator asked me regarding his floral pattern.

‘If they’re forcing you to use the door to get out of the room then it’s working.’

This cove installed a huge mirror thrown out of a department store which went from floor to ceiling.

’It gives you a feeling of space, doesn’t it?’

Why look there’s a whole other room in there, ’I said, ‘and there’s a man who looks just like me. I’ll leave him here with you while I go on my way.’’

His living room had been decorated with paper chains and lights that projected psychedelic swirls on the walls.

Living large, one artist occupied a warehouse by just himself and his wife. He had much more opulent, grandiose taste in wallpaper.

‘You’ve got such a lot of space. You live in this huge place all by yourselves?’ I asked him.

‘As far as we know. If there are any others living here too, they do so without our knowledge.’

‘Don’t you get frightened here on your own in a big house like this?’ asked a policeman carrying out a check on the property.

‘Only when people like you say things like that.’

‘ One day in the street this artist raised with me the matter of his huge electricity bills. I suspected it would have cost a lot to heat his huge place. He told me ‘You’d be most welcome to come by and give me some hints for lowering them. My door is always open.’

One long term occupant with an obsessive compulsion got carried away with this sense of artistic licence and painted his squat over and over again.

‘You’ve splashed a bit of paint around, I see. ‘It covers the cracks. I’ve been living in this place for a few years now, and every time I paint it, it gets me down. I look around, and I think, well, it’s a little bit smaller now. You know, I realize it’s just the thickness of the paint, but I’m aware of it. It keeps coming in and coming in. Everytime I paint it, it’s closer and closer. I don’t even know where the wall sockets are anymore. I just look for like a lump with two slots in it. It looks like a pig is trying to push his way through from the other side. That’s where I plug in.’

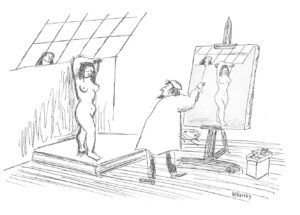

As well as painting walls squatting allowed some to purue painting canvases. Few young artists could afford to pay rent on housing and studio space at the same time. Fewer still could afford the luxury of a vast exhibition space they could do what they want with. “I’m damned if I’m going to work six days a week to pay for a workroom,” said this painter of unclothed figures. ‘This hitherto ignored large scale regenerated site gets my juices flowing without commercial restraints.’ It also provided him with keen spectators.

One art student decorated the house, including hand-painted lilies on peppermint-green walls. ‘The same as Cecil Beaton’s when he lived here in Paddington.’

‘The world is what you make of it,’ said Piers with faint traces of west country burr. ‘If it doesn’t fit you have to make alterations.’

This didn’t work well in the case of the guy who installed a skylight in his squatted ground floor flat. The people who lived above him were furious.

Or the naturist I had encountered in his stately loungeroom standing near the window. ‘Why are you all naked?’I asked him?”

‘Why can’t I be?’ he answered. ‘This is how God made me. This is my home while it lasts. There’s no one else here besides my missus.’

‘But why are you wearing a tie?’ I asked.

‘You’re the answer to that question. What if someone drops in to visit me?’

This jaybird took advantage of what he saw as his private backyard to chop down some high bushes blocking the sunlight. He could now get some overall suntan. ‘

‘It’s too hot to wear any clothes today, ’he told his wife. ‘What do you think the neighbours would say if they saw me with nothing on?’

‘That I married you for your money. ’she said laughing.

Unaware to him the foliage failed to adequately separate the view of his garden from that of his next door neighbour’s mansion.

Looking out her window, she saw his nakedness and was shocked indeed.

She called the police who charged him with indecent exposure.

When the roles were reversed and and he happened by chance to spy her topless, she rang the police who did him for voyeurism.

Our members learned not to take advantage of their ‘freedom’ to the disadvantage of their neighbours.

‘At 4 o’clock every morning,’ one squatting dance student told a friend, ‘my neighbours hammer on my bedroom door, on the walls, even on the floor and ceiling. Sometimes they hammer so loud I can hardly hear myself clicking.’

Squatters work tokens, financed by the street fund, and subsidized by ‘That Tea Room’, were introduced as a means by which unemployed people could work for the community and benefit directly. A one hour work token was exchangeable for a meal at ‘That Tea Room’.

People would be deployed on a variety of tasks: printing leaflets, petitions and news sheets, writing letters, handling the legal defence, organizing social events, raising money through jumble sales, finding new squats and liaising with the press. A number of Maida Hill squatters helped Radio Concorde, an illegal radio station which often broadcast squatting news. The station frequently broadcast from 101 Walterton Road, home of the 101ers. Along with others, Piers was arrested for illegal broadcasting.

Piers took upon himself most of the necessary leg work, negotiating with owners and housing authorities, lobbying, arguing vigorously at meetings all over the city, taking resolutions to conferences and preparing alternate plans. He facilitated communication with many spread out squats, a task made doubly difficult by the temporary and unstable nature of most and the consequent absence of telephones and contact addresses. Piers published a newsletter, ‘EASY’ an acronym for Elgin Avenue Squatters, Yes’.

‘Without a publication containing information about our activities, you cannot unite a community,’ he explained.’

Most importantly he and others sought out solidarity support from other groups. We gained this from, amongst others, the local member of Parliament, the trades council and the federation of local tenants and residents associations.

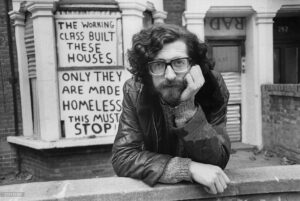

One GLC councillor, representing the owners, spoke of the strength of our organization and spirit. One name constantly cropped up in news accounts of our deeds was that of Piers Corbyn, a guiding light for me,.

A lasting success of his time as President of Imperial College was increased student representation on college boards and committees. He petitioned the Queen asking for students to be given greater say in the governance of the college.

I asked him once as he shone a torch up the tree I was climbing, ‘ ‘How can we achieve housing for all? How can we get any joy confronting such an intimidating force of large property owners, police and officialdom ?’

Piers replied, ‘Even though it may seem impossible, by steadily taking them on, one step at a time, a little at a time, we can chip away at them, we can take them down. Change comes about when lots of people do little things, which at certain points come together, and then something good and something important happens. I’m talking about a multitude of small acts in unison.’

‘Little strokes fell great oaks.’

‘Exactly. Let me put it another way. Do you know your physics, Allan?’ he said, hitting gently and repeatedly the front column of the building we were about to enter.

‘If you tap repeatedly on the a building post, and the tapping is relentless, it creates a rhythm. If you do that long enough and steadily enough, it will feed back. The frequencies will align, the molecules will scramble, and the whole thing, the whole building will come apart from the inside and collapse in on itself, and all come tumbling down. The structure of private propertied class domination comes apart.

Do you know which way that takes us? The way where we can fight the belief that political decisions are pre-ordained and that participation is futile.’

An all-round good egg, self sacrificing, no one personified squatted London more than Piers. He was always willing to put himself out for other people. Tousled, a shock of dusky hair, glasses held together by sticky tape, he spent no time at all on colour co-ordinating his wardrobe. His bedroom at number 19 doubled as his office. Piles of papers, clutter and all, seemingly willy nilly blanketed the floor. Any semblance of order was lost on the casual visitor. On one occasion I assayed tidying up this measured spread to Piers’ consternation. Extremely focused, with his sharp eyes missing nothing, he knew where everything was and didn’t need it disturbed. Putting anything extraneous aside, he avoided all distraction. This was true conviction. He planted quite a number of little acorns which would grow into oak trees.

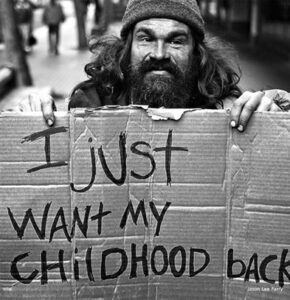

In Elgin Avenue we housed anyone looking for a home and those just looking for shelter, those who had pounded the pavement, knowing every crack, sleeping rough. While there may have been some people who squatted for ideological reasons, the on-going driving force for the thousands of people who did so was the lack of any other viable choice of a place to live. Some had been discriminated against by landlords and landladies.

‘Back in the day,’said Piers, ‘there used to be signs on the boarding houses saying, ‘No Irish,no dogs!’ Then it was, ‘No Irish, no blacks, no dogs. Then just ‘No blacks,no dogs.’ Things change.’

‘Unless you’re a dog. ’I replied.

‘I told my landlord I wanted to live in a more expensive apartment,’ said one man coming to our office. ‘He jacked up my rent. I’ve been slung out of so many flats that all my furniture has wheels.’

One lady and her infant told us, ‘I don’t have anywhere to go. I’m not married and my parents have disowned me.’

I reassured her we would fix them up: ‘If you don’t have any place to go, it’s probably a good idea to stay where you are.’

Some were referred by the Ruff Tuff Cream Puff Estate Agency which published bulletins of squattable empty properties all over the country. Desperately homeless families were referred by the Social Services Department of the GLC, housing advice centres, probation officers, and yes, our friends the police. We organized for them all to maintain their situation and live in well-knit harmony with others. We accommodated a patchwork of people- workers, students, tramps, waifs, actors, battered women, communards, ‘together’ people, roughnecks and nutters.

There were the rootless and the uprooted, especially the Irish escaping The Troubles, those facing foreclosure, disabled and elderly people and 30 children.

The only race that mattered was the three legged kind.

Well over 100 people lived on Elgin Avenue for various lengths of time. There were no gateway requirements. Everyone had a right to be there. People just had to get along, forming ‘unholy alliances’ with others they never would have in any other way. What we all had in common was that we were under threat of being chucked out-the same psychology you had during the Blitz. A community forging itself because of an external threat.

Another Day in Elysium.

Because of its size, centrality and openness, our organisation attracted some of what are called ‘skippers’. Skips being those large containers waste materials are dumped in.

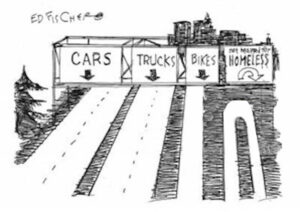

Most were rough sleepers who just wanted a roof for the night. Britain has a long history of such homelessness.

Often these destitute people didn’t even stay there during the day. Some had resorted to sleeping in abandoned cars.

So many had been living on the streets for three, four, five years, and they couldn’t handle living in a building.

They’d just forgotten. Knock knock jokes were wasted on them.

One foot in the gutter, some were so removed from settled society, they couldn’t see the point of getting their lives back on track .

‘Do you want a room with running water?’ I asked one dreadlocked skipper, the sole flapping off his shoe.

‘What do you think I am? A salmon ?’

‘You look a bit green around the gills. Where have you been spending these cold nights ?’ I asked him?’

‘You’re always looking for a back door into a building, or at least an open doorway where you can doss down for the night. ‘

‘How do passers by react to seeing this?’

‘Some curse us and tell us to move off. Generally they just ignore us and keep walking.’

‘Any other good spots.’

‘I’ve been spending the nights around railway stations. That’s where there are other street sleepers, curled up in the photo booths and phone boxes and stretched out on the pavement. Every couple of hours we are all moved on by the police. They don’t care where we go, they only want to keep us awake. So the man in the photo booth will lurch to the phone box, and the man in the phone box will roll onto the pavement.’

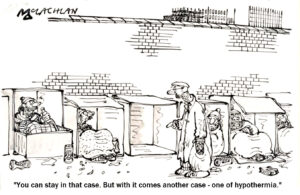

‘How do you find this experience?’

‘It can be terrifying. Every minute feels like an hour, and every hour like a day. You’re very vulnerable when you’re sat out and you’ve barely enough to keep yourself warm.

It gets desperate and it gets lonely, you are always trying to protect yourself.’

‘And your days?’

‘I find libraries to sleep in by day. I’ve spent winter in church shelters, sharing dormitory rooms. All the snoring is the pits,’ he said.

In your situation it must be difficult to form a steady relationship with a partner.’

‘You’re not wrong. I was on a date with a bird I met outside the supermarket.

I confided to her, ‘I have to admit, I’ve spent a small amount of time inside.’

“Oh my god!” she shrieked. “You’ve been to prison?”

I said, “No, I’m homeless.’

‘Are you resentful about that?’

‘It doesn’t make me feel good. People can be so insensitive, Like yesterday I had dinner in a soup kitchen. At closing time, the manager announced, ‘Come on, finish your meals, ladies and gentlemen, some of us have got homes to go to.’

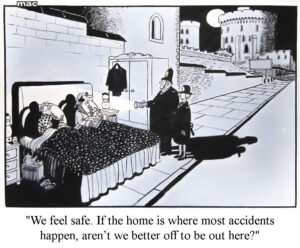

‘Look on the bright side of things,’ I said. Answer me this. Are you more likely to die on the roads or at work than at home.’

‘The first two both sound the most dangerous .’

‘The truth is improvements in road safety and workplaces mean that homes and leisure pursuits now cause far more injuries and deaths than car crashes and industrial accidents .’

One ageing couple who appreciated the risk in everyday situations took it quite literally.

In their old living room they had been scalded by hot cups of tea, burned by the gas fire, tripped on rugs and electrically shocked trying to fix a faulty plug.

Gone to the Dogs.

Other skippers got to like the idea of being more settled. One eccentric lady, born into the purple, had fallen down several rungs of the social ladder at once. She had taken to living with a pack of dogs in the not so well appointed shell of an empty house, a slug infested sieve that let in wind and water.

The dogs were both her best friends and her helpers.

When I knocked on her door, a neighbour yelled out, ‘She’ll be back in a minute. She’s gone to get some dog food. Is she expecting you?’

‘Only if she’s psychic?’

‘Maybe a bit psycho.’

When she returned she had a job opening the door.

‘The lock jams every now and then. The good thing is that you can hear when anyone is trying to break in.’

‘There’s a terrible smell in this place, ‘ I said to her when I accompanied her inside.

‘Maybe it’s the drains.’

‘It can’t be the drains, ‘ she replied, ‘this place doesn’t have any. And there’s nothing to worry about. As you can see the canary’s still alive.’

It didn’t have any table, cupboard or -come to that-any other articles that make life functional either. Nothing except for an old armchair and a rusty prehistoric fridge. She was in the habit when hungry of constantly returning to it in hopes that something new would have materialized.

As I sat beside her in front of a blazing open fire I asked, ‘Wouldn’t you like to have some furniture? We can arrange to find you some.’

‘I had a chair once.’

‘Where is it?’

‘It’s warming us right now.’

In her travels all kinds of stray dogs attached themselves to her troupe .

One was a sheep dog. It didn’t have fleas. It had moths.

Another was half Collie, half pit bull. It might bite off your finger but then it would go for help.

Once a dog lover approached to asked her, ‘Does your terrier bite?’

‘No.’

He said, bowing down to pet him, ‘Nice doggie.’

The pooch barked and bit him in the hand.

‘I thought you said your dog did not bite!’

‘That’s not my dog.’

One of her dogs got into a set-to with another. ’Look at my poor little terrier,’ she cried. ‘ A Doberman bit him on his hind legs and shook him around the belly.’ His wounds were indeed horrific . His ribs and jaw were broken.

‘That’s horrific,’ I said, ’That’s left him in such a sorry state.’

‘That much is true, but you should see the other dog.’

Dropping a big hint I asked her, ‘Do you know the Battersea Dogs home?’

She replied evasively, ‘I didn’t even know it was away.’

‘The dog’s home has been burgled – police say they have no leads.’

We looked for a replacement dwelling for her, one where she didn’t have to dance around buckets. A local tipped us off to a flat that he had described as ‘spacious’ . ‘Wait a minute,’ I said on inspection, ‘this flat doesn’t have a ceiling.’

He answered, That’s O. K. the people upstairs don’t walk around that much. But they might drop in now and again.’

‘I said to him, ‘I thought you said you have experience in estate management?’

‘No word of a lie. I used to have a Mini Minor estate, ’he replied, referring to the British station wagon.’

We looked through the latest bulletin from the Ruff Tuff seeking a suitable house for her. One, a closed down former three star hotel with just a hole in the roof now allowed any potential occupants the chance to view all three. It was described as having ‘a heavenly view’. 36 St Luke’s Road to which the 101ers moved was unavailable. It was listed as ‘would suit astronomer’, because it had no roof at all.

We eliminated this next one from consideration right off. It’s qualities were described as ‘Oozing charm, uninterrupted view with transport at door’. The bulletin translated these real estate euphemisms into plain English. They described a house that was ‘damp’, with a ‘ large hole in the wall’, where you had to ‘look both ways when stepping out’.

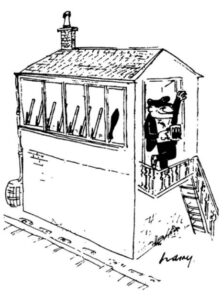

One former rail signalman reported to Heathcote Williams who ran the ‘Ruff Tuff’ agency that there was space available at the rail station where he had worked.

Owing to changes in rail technology the station was abandoned and he lost his congenial job .

The former refreshment room was available to anyone who would assist him in fixing up the place.

Heathcote was a keen reader of Charles Dickens and recalled that he had written a book called ‘Mugby Junction’. In Chapter Three he had made a scathing attack on railway refreshment rooms and their staff. One of his stories satirizes the refreshment rooms where Dickens was humiliated by the manageress when he was ordering a cup of coffee. She refused to pass him the sugar bowl until she had been paid, clearly not recognising the celebrity author.

‘You show signs of offering better hospitality than that silly woman. I hope as the new operators you will refresh the premises.’

‘We will carry out minor repair works to the building’s facade and supervise the landscaping of the extensive grounds. We plan to grow a garden and make the land more attractive by adding ornamental features and planting trees and shrubs.’

In London as elsewhere proximity to transport was and remains an important consideration in choosing one’s residence.

The best solution for us was a ‘hole in the wall’ described as having ‘unparalleled privacy’ meaning it was ‘ impossible to find.’

‘It’s not too big, it’s not too small, ’reported back our scout. In fact it’s just right for someone with pets.’

‘You know which one it sounds like. The one that used to be occupied by the blonde girl with the bears.’ I said.

We transported our bag lady and her animals to an empty house in the country where she was happy until the old bill brought them back to town.

She was not so impossible to find.

When she started roaming the London streets again with her pack I imagined the dogs thinking, ‘Man, this is the longest walk ever.’

After the odd bod had left us I entered her old quarters and was startled to find to find a young man in occupancy. ‘Oh! I didn’t expect to see anybody here.’

‘I’m not back from the grave, you know.’

I informed him of the services available to him. As I was doing so he opened the fridge he came across it’s sole contents-a half bottle of port, two empty beer cans and an ancient piece of steak.

‘Would you care for a drink, Squire. I like to be hospitable to my visitors.’

I guess I’ll try the port. I suppose a beer is out of the question?’

‘They’re reserved for my guests who don’t drink.’

As he gazed on the steak, licking his lips I said to him, ‘I wouldn’t touch that if I were you. It might be contaminated. It’s safer to eat at ‘That Tea Room’. Red meat might not be good for you, but blue green meat—that’s really bad for you!’

He listened to my advice and decided to throw it out the window immediately. The following day walking by outside I noticed a cat lying under the window the ninth of all of it’s lives run out.

This was a veritable baroque cavalcade of humanity. A visual reminder of how much of a social movement takes place in a profusion of lives, under the surface, among the unfamous.

I remember one apprentice bricklayer who came to us, living hand to mouth, as he had been learning the craft of building houses. I need not point out the irony there.

‘I’ve been laid off from work,’ he said, ‘my rent is due. I went to the bank to see what they could do. The manager said, ‘Young man, it looks like bad luck’s got a hold on you.’

One elderly couple had been forced out of their council house, the one they’d lived in for 50 years, paying for the property many times over.

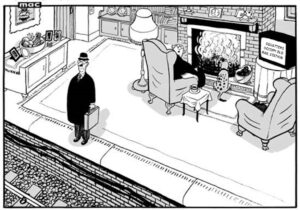

Having clattered about on the roulette wheel of London’s housing market, I was eager to get out of the restrictions of life in private rentaville, hemmed in by junk furniture and petty regulations.

One of the first landlords who I’d spoken to had showed me a ‘bijou apartment’ the size of a large cupboard with tiny windows, yellowing curtains, and fading, flowered wallpaper. The front and back doors were the same door.

He occupied a bigger unit in the same building.

‘Rent’s a hundred a week including the service charge,’ he pointed out. ‘Four weeks upfront, four weeks notice. Cash, no cheques, no excuses and we’ll all be happy.

He advised me: ‘Before you can sign the lease, let me point out I run a respectable establishment here. There are a few rules I’d like you to keep.’

‘And what might they be?’

No late phone calls, no women visitors, no funny freaks. no wacky baccy, hallucogenics or magic mushrooms.

No acquaintances with sexually communicable diseases.

No foreign friends, no children, No dogs, no cats.’

‘You’re having a laugh, aren’t you. There’s no room to swing a cat. Nor for swingers parties or threesomes. I’m sure the mice are hunchbacks. Even if I wanted to rent this crummy claustrophobic cubby hole, you wouldn’t have to worry about any visitors of mine. It’s so small that when they walked in, they’d be already coming out. If they turned around, they’d be next door. If I were to talk to myself, one of us would have to step outside to reply. It’s so small I’d end up sleeping with the doorknob in my mouth. And how can you call it an ‘apartment’? It’s crammed tight right next to all the others.’ ‘I did warn you there was one tiny flaw. Oh, did I mention. I’d need six months rent in advance.’

‘And what would you like me to pay with? A sack of flour, some cowrie shells or coloured beads?’

Seeing I wouldn’t be home much, I had on first entering considered it’s central location. I had to go outside to change my mind.

Not knowing when any new landlord might take it into his head to evict, I had nothing to lose by moving to Elgin Avenue. If I played the game right and housed myself legally, I still got thrown out anyway. I myself arrived on the avenue after the next digs I shared with teaching colleagues folded up after burglars broke in.

As did the police, backed up by Alsatian dogs, at my new home, the self-contained, commodious basement flat of Number 19., acquiring us as a target for an early wet morning lightning raid. I let them in following their banging heavily on the door at 4AM.

‘If you’re after a cup of sugar, I’m afraid you’ve come to the wrong door,’ I said as I opened mine, ‘or are you after my overdue library books? After they pushed their way past, ignoring my request, ‘Shoes off! I asked them, ‘Are your pets housebroken?’

‘I can only vouch for Fluffy.’

I then asked them, ‘Is there a problem, officers?’

‘Not yet,’ replied the head intruder. ‘Now what’s your name, mister?’

‘Is this where I say, ‘What is all this about? ’And he says, ‘That’s enough, I ask the questions?’

‘That’s right, so just answer the questions. Wouldn’t you like to know why we’re here?’

‘I find in life it’s always best not to spoil a surprise.’

‘ Or maybe it’s not a surprise at all. Who exactly lives here?’

‘Maybe if I knew why you wanted to know, I could remember.’

‘You’d better jog your memory quick smart. You don’t have any choice but to do so.’

‘Whatever it is you want to know, I didn’t do it. Nobody saw me do anything. Wait, don’t tell me-you’re here to catch people you consider don’t have any rights.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘You just did.’

‘We’re here to do our job. Protecting the public.’

‘So why precisely are you here?’

‘Let’s just say we didn’t come here to get out of the rain.’

‘Now this is just me guessing but do you have reasonable grounds for your suspicions? What exactly is your line of inquiry? Do you have a search warrant?’

‘Just be quiet.’

You did say that politely but it doesn’t make up for the fact that you’re in contravention of the legal code.’

Unfortunately so too was I. All the signs were there.

‘We could bust you for illegal possession of public property,’he said, pointing to the wall on which hung an old road sign I’d souvenired from a skip. It’s white lettering on blue ground read ‘Turn Left.’

‘I apologise unreservedly, Officer. It just followed me home. I’ve been intending to hand it in to Harrow Road Station.’

‘And this ‘Exit sign’. How do you explain that?’

‘It’s very rusty. Just look at it. It’s on the way out.’

‘I just thought I’d let you know.’

‘ I appreciate that.’

‘ Is that painting yours?’he said, looking at another wall.

‘Bought it at Portobello market.’

‘It’s rubbish ?’

‘It’s a mirror. Now do you you mind telling me what you’re looking for?’ I asked.

‘We’ll ask the questions if you don’t mind. You won’t object of course if we look around, will you?’

‘Go ahead. Poke about. Sniff around. Time is no object. Make yourself at home. Don’t mind me. I just live here.’

‘We won’t keep you up longer than necessary.’

‘Why should I mind? What’s a little sleep?

‘How many people live here? ‘he asked with a leering glance.

‘There’s just me at the moment.’

‘Just you, eh? Then why’s your table set for three?’

‘That doesn’t mean anything. My alarm clock is set for eight.”

‘What about this? ’the orificer asked his colleague, pulling out a taped shoe box from under my bed. I kept passport and assorted documents in it. He put his ear to it.

‘I said to him, ‘ Isn’t this where you say to me, ‘We know what makes you tick, punk, and we have ways to make you tock!’

‘Doesn’t tick, does it?’ replied the orificer.

‘Only in wet weather. English weather, ’I assured them. ‘In the Bible, God made it rain for forty days and forty nights. That’s a pretty good summer for here as I’ve learned.’

‘At least the rainwater is warmer.’

“You know what catches my eye in this country?’ I said, aiming to humour him. ‘Short people with umbrellas.’ He didn’t laugh. He too was short.’ I held my hands together in the air and waved them. ‘Get it—umbrella,’ He still didn’t laugh at the subject- my imaginary brolly. It must have gone over his head.

I came to realise the extent to which the climate of England had been the world’s most powerful colonizing impulse.

‘Now would you and your pets like some mince meat?’ I offered as they sniffed around. ‘Oh, that’s right, I remember now. You can’t eat or drink on duty. Perhaps I can help you find…’

‘Don’t worry, Mr. Davis. If there’s anything of interest to us, we’ll find it. We have all the time in the world.’

After they had conducted their search some time, it was obvious to them they’d find nothing. I just wanted to turn in again.

‘If it’s Easter bunnies you’re looking for, it’s a bit early. Now you don’t object to my going back to bed, do you? I’ve got a habit of sleeping late, often right up to 6. I’ll leave the front door unlocked. You can storm in anytime you like. Bring your friends and pets for the festivities. Work the place over. We could have a policeman’s ball.

‘Nice doggies. You must be Fido, and you must be Fluffy,’ I said to their pets, giving them a pat as as they were being led out. I would never have dared escape from these canine constables. They knew all the tricks. If you’re being chased by them, you can’t go through a tunnel, onto a seesaw, jump through a hoop of fire or form moving pyramids. I’m not trained for that.

‘These dogs look well behaved, I said to the policeman. ’You probably heard some dogs around here have been chasing people on bikes.’

‘Well they’re not ours. Our dogs don’t even own bikes.’

.What had gone through my mind was that their handlers might try to to plant incriminating evidence on me or my home for later discovery and use in prosecution. They had tried twice to fit Piers up with drugs but couldn’t make their charges stick.

They must have been disappointed our’s wasn’t the London headquarters of the Irish bombing campaign. Their excuse: the IRA had bombed a pub in Guildford in November 1974 in which five were killed and one the following month in Birmingham. The public anti-Irish hysteria following these atrocities was whipped up by the tabloids. It would have seemed only natural to some readers that terrorists would gravitate to living amongst those who the same rags reported wouldn’t hesitate to occupy your home if you vacated it briefly for repairs. In the final analysis the last place a terrorist, particularly a well funded Provisional would choose to stay would be in a residential limbo somewhere between legal and illegal. A professional terrorist instinctively wants to blend in more in the mainstream than many a squatter. Otherwise his cache would be vulnerable and he would come in for occasional police raids.

The squat in Kilburn where Gerry Conlon had set up camp was raided by the police three times in the months before the Guildford bombing and on each occasion his flat mates correctly identified themselves. The police didn’t lay off fitting up false charges against them. Leaving the Belfast scrap metal industry behind, Gerry had shipped out to escape the clutches of the IRA. They were out to blow his kneecaps off. He had brought the heat of the security forces upon them. Gerry was falsely implicated when apprehended under the Prevention of Terrorism Act which allows the suspension of civil rights. He spent the next fifteen years in jail. His story is told in the film “In the Name of the Father”.

Here Comes The Neighbourhood

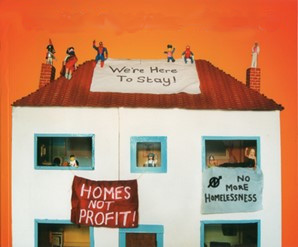

We demonstrated our opposition to these powers and proposed criminal trespass laws to be used against squatters, students and workers occupying workplaces. Finding strength in each other we backing each other to the hilt when it came to a pitched showdown. We put the word about: ‘Make a big scene, let them know what we really mean.’

This familiar scene with its regular role call was frequently played out on household screens. The large police presence to ensure public order in civil matters such as this. The police spokesman explaining their role as being to observe the evictions, prevent any breach of the peace, and ensure the right to peaceful protest was balanced with people’s right to go about their lawful business. ‘ One side,folk. Can you step aside, please!’

That’s when they sent in the clowns. The bailiffs arriving in their panel van to batter down the doors and help us on our way.

The police forming a line to protect these biggies and to warn us off: ‘Stand down. We appreciate your fan club wants to get close but let these men do their work.’

There’s something to be said about being a bailiff. You can assault people in broad daylight if you are standing next to a policeman. It must have been wearying for them to be hounded relentlessly with such mundane questions as ‘Where have your wife and children gone?’ And ‘How much are you selling your soul for?’

The large crowd assembling to support the squatters in their attempt to resist the force majeure of bailiffs, fully equipped with steel cutters, sledgehammers, and even cherry pickers . If these couldn’t get them through the doors and windows to get us out they would try to winch these fittings out with grappling irons.

The plain-clothes man masterminding things, with a beck and a nod, indicated to the uniformed men any he considered troublesome to be singled for nabbing. These being fingered as ‘You, you and you. No, there’s no point hiding your face, You’re done!’

To get them inside the van, they seized any reluctant to go, any slowing down their operation.

Then working to detach them from any ‘lock-ons’, they pinned arms behind backs, frogmarching them out, filling in the vans, clanging the door shut, off and away.

To the mingled cheers and boos from the footpath, some in those arresting moments would mount the steps of the paddy wagon like aristocrats going to the guillotine, still protesting defiantly away until the steel doors clanged shut. Others of those pinched going limp, others resisting thrust bodily into vehicles, others thrown back into the crowd. Lots of noise, the thump of bodies, the scuffle of feet, the vigorous rocking of the wagon coming through.

Thinking globally, acting locally we banded together arms locked to challenge every eviction both in the courts of law and public opinion, and in the streets, putting thorns in the sides of unfeeling bureaucrats and spanners in the bailiffs’ works. This is where our Irish brothers came to the fore, merry men you could count on, no slouchs when push came to shove. Forming steps with their hands for climbing above. Going up the side of a house like a ladder.

It was always essential to make double sure the targeted property was empty and the coast was clear.

I attended the court hearing of two paddywhacks charged with aggravated break and enter. They had been nabbed dead to rights trying to climb into a vacant house. Once in, they would have been home and dry, able to argue that a window had been left on the latch. With no sign of forcible entry they were protected by law. Unfortunately they were without a lookout.

‘Give me a hand, Mick’, called O’Reilly to his mate on the ground below.

‘Hold it right there, Spiderman! I’ll give you a right-hander if you don’t come down at once’, was the reply. It wasn’t his mate talking but a policeman.

‘What’s all this then? Who do we have here? What’s your game, gentlemen?’

‘O’im distributing ‘The Watchtower’.’

‘You’re pinched you are. Now where are you from? asked the arresting officer, patting O’Reilly down. ’Where do you pitch your tent? Now let me take a wild guess.’

‘Ye’d never guess. Oi’m a son of Erin.’

‘Oh really.’

‘No. O’Reilly.

‘In that case I’ll talk slowly’, he said, taking out his notebook. ‘And what do you do for a living?’

‘I’m on subsidence.’

‘So do you do anything useful with your time.’

‘I’m a scoutmaster.’

‘Well don’t ever try to help my mother across the street.’

‘ Oi refuse ter answer dat on de grounds dat it might incriminate me.’

‘And what about your partner in crime here. Where are you from, my friend?’

‘I’m from Alcoholics Anonymous.’

‘Your name?’

‘Well we’re anonymous.’

‘No funny business now. Give me your name and tell me what you do?’

‘And what about your partner in crime here. What do you do, my friend?’

‘Oi’m Mick Molloy, Ossifer. he said, talking slowly. ’Oi work in construction , aye. Oi work on da buildin’ sites,’ he replied .

‘O. K.,’said the bogey, trying to catch him out, ‘so you won’t mind if I ask you to explain the difference between, say, a girder and a joist?’

‘Ah,’ said the navvy, wanting to put P. C. Plod in his place, ‘Dat’s a tricky one, any difference inadmissable if true, hmmm. Girder and a joist you say, a girder, and a joist….. hmmmm”

‘There was a long pause until he dealt the answer.

‘Girder wrote Faust and Joist wrote Ulysses!’

Unread and unschooled, the policeman was caught completely flatfooted.

‘Have you got a plumb line?’ he asked.

The one Oi usually use is, ‘’Av yer got a plum? But it’s pitiful. Oi both ‘ear an’ see yer don’t ‘av wan,’he said, looking in the bobby’s mouth. ‘Now are ye going to read me my rights?’

You have the right to remain silent and if you don’t, you cat lick leprecoon, you’ll end up with a split lip.’

‘Pogue mo thoin. Oi’ll waive me rights.’

While patting hm down the policeman felt an interesting object in Molloy’s pocket. A small rubber statuette of a little bearded man wearing a coat and hat attached to a key chain.’

‘What’s this, Molloy?’the bobby demanded as he unclipped the chain.

‘It’s my lucky leprechaun charm.’

Well this mischievous midget’s not working for you today I’m afraid, said the cop, swinging the chain against Molloy’s cheek.

He then called for backup to help him bring in the pair for further questioning.

His colleagues gave him quite a ribbing about his capture as he escorted Molloy into the Harrow Road nick.

Later on two men who spoke with heavy lilting accents were not helping the police with their inquiries one little bit.

After the fact the men were brought before the court. The clerk announced their matter by name in the list. Upon hearing the announcement, their legal representatives approached one end of the bar table facing the judicial member and said in turn:

‘If Your Honour pleases, l appear for the Mr. Molloy in this matter.’

‘May it please Your Honour , l appear for the Mr. O’Reilly in this matter.’

‘If Your Honour pleases you, Sir, Oi appear to be not sure why Oi’m here.’ declared Fearghal O’Reilly, forthright in expressing his thoughts.’

The bailiff said to him, ‘When you are addressing the court you must say ‘Your Honour.’

“I don’t know whether he has any or not. Moreover I don’t recognise this court,’

‘Why not? Is it because you’re Irish?’

‘It’s because it’s been done up since I was here last.’

He had been out on the rip one St Patricks Day and took a bus home. That may not be a big deal to most people, but he’d never driven a bus before.

After Fearghal and friends abandoned their transport, Fearhal was arrested for chorusing and carrying on and was brought before a different magistrate. The judicial officer was just about to address Fearhal when there was a loud commotion from the gallery. The magistrate angrily pounded his gravel on his table and shouted, “Order, order!” Mick immediately responded, “Thank you, your honour, I’ll have a whiskey, make it a double.”

The magistrate on this latest occasion asked Fearghal, ‘Have you been up before me before, Mr. O’Reilly?’

‘Oi don’t know, Your Honour, Fearghal answered slowly, ‘What time do you get up?’

‘Would you please project your voice to the back of the court, Mr. O’Reilly. It’s not just your strong accent but a matter of volume.’

He then asked Fearghal for his address. He replied, ‘No fixed abode, your Honour.’

The beak then asked Mick Molloy for his. He replied, ‘ I’m in the gaff above Mr. O’Reilly’s, me learned friend’.

‘And have you been up before me before, Mr. Molloy?’

That Oi have, Your Honour. I got into a barney with a friend.’

‘Couldn’t you have settled that out of court?’

‘That’s just what we were doing when the police came and interfered.’

‘Now as for this entering other people’s property, there’s too much of this illegal trespass going on these days. How do you justify yours?’

‘Oi wish to plead contemporary insanity, your Honour.’

‘You’ve got to ask yourself, Mr. Molloy, ‘Do I keep doing the same thing, or am I going to choose a different path and question my convictions?’

‘But Your Honour, Oi don’t ‘ave any prior convictions.’

‘Mr. Molloy, I want an explanation and I want the truth.’

‘Well, which is it Your Honour ?’

‘Mr. Molloy, Some might be taken in by your air of rustic humbleness . I find it both put on and off putting.’

‘Oi beg to disagree, your Honour, as does me missus. Oi am appealing.’

When came the turn of the arresting policeman to outline his version of events, the magistrate asked him, ‘Officer, Did you actually witness Mr. Molloy climbing up to the window aiming to get into the house?’

‘No, it was told to me by a wise old swami from Southall. Of course I witnessed it.’

‘Please speak more respectfully in court, Officer. As a representative of the law you should know better. If you spoke like this to these two men before me, I’m not assured of your sense of esteem. Case dismissed.’

All the while we argued that it’s plain wrong to leave properties empty and neglected.

That those responsible produce diddly squat. We put pressure on the governmental housing agency to compulsorily purchase others. We put pressure on it to exercise it’s responsibility to allow homeless people to live in all until decent affordable alternatives were available. By abandoning properties, it signalled brass necked lead strippers to start work. This would lead to rain drops showering through ceilings, soaking everything, like someone turning on sprinklers inside . The waterlogging damaged walls, floors and the electrics.

Then came their second line of attack. Deterrence.

Demolishing houses long before sites were actually required, fencing off the empty sites which became used for dumping rubbish, with half demolished houses butting up against people’s homes. Otherwise they gutted, sealed them up and made them uninhabitable . What the local authorities would do was to brick up windows, seal sewer connections, concrete up lavvies, smash holes in roofs, rip out staircases, floorboards, internal doors and wiring, saw through support joists, leave behind broken windows, unfurnished hallways, strip fittings and appliances, and generally vandalise the properties they were supposed to have due diligence for, to stop people living in them. They tried this on in Elgin Avenue attempting with some success to structurally weaken occupied adjoining houses, demoralise the occupants and make the streetscape more of an eyesore.

Demolishing houses long before sites were actually required, fencing off the empty sites which became used for dumping rubbish, with half demolished houses butting up against people’s homes. Otherwise they gutted, sealed them up and made them uninhabitable . What the local authorities would do was to brick up windows, seal sewer connections, concrete up lavvies, smash holes in roofs, rip out staircases, floorboards, internal doors and wiring, saw through support joists, leave behind broken windows, unfurnished hallways, strip fittings and appliances, and generally vandalise the properties they were supposed to have due diligence for, to stop people living in them. They tried this on in Elgin Avenue attempting with some success to structurally weaken occupied adjoining houses, demoralise the occupants and make the streetscape more of an eyesore.

In this vendetta, they instructed service authorities to disconnect gas, water and electricity. Using back door methods of harassment, London Electricity Board workers were instructed to dig holes in the street where John Mellor lived, intending to cut off supplies, but an instant picket knocked that on the head. In the days that followed, the holes were successively dug up by the workmen and filled in by squatters. What followed was a widely reported campaign involving court cases and occupations to decide the right of squatters to receive provision of this basic source of energy.

The BBC World News, January 11, 1974 reported as follow: ‘An occupation of the London Electricity Board showroom in Notting Hill Gate today by a a group of about 100 squatters demanding the right to be connected to electricity was brought to an end when the Special Patrol Group smashed their way in upstairs. Initially the police stood 200 yards away while crowds inside and outside the building waved and chanted ‘Electricity for all!’

The police had been locked out while senior LEB officials were brought in to negotiate. After the police entry the occupiers were dispersed with 31 arrests.’

Most were eventually fined though one man received a six month prison sentence. While the GLC and LEB backed down due to the unpleasant light in which they were exposed, allowing connection to Walterton Avenue, the matter of the right to connection remained left to the the discretion of the authorities and continued to be determined on a case to case basis.

As Minister for Energy, Tony Benn stated in Parliament in 1975 that squatters would be treated as any other occupiers.

‘Are they being treated so in practice?’ top ABC reporter Paul Lyneham asked Piers. Paul was doing a story on Elgin Avenue for ‘Four Corners’.

‘In spite of this directive property owners continue to be able to deny us gas and electricity supplies. These dogs in the manger divide people by accusing those of us most insistent on receiving attention of jumping the ‘housing queue’, of being less ‘deserving’ than those at the official ‘head’, even though most squatted houses are not intended for immediate use.’

Why would anyone other than property owners regard keeping squatters out a good thing? They have the initiative to solve their problem rather than sitting round and waiting.

‘This is not Russia’, said Piers. ‘Why should people here or anywhere have to queue for basic requirements? The ‘waiting list’ is a political device to divide and weaken the real housing movement. It’s designed to encourage those who get a roof over their heads to forget others and pull the ladder behind them. The homeless are not responsible for homelessness. For the vast number of people on it, the housing waiting list has become exactly that, a list upon which they wait—and wait— and wait.’

We put into effect grassroot procedures whereby everybody could voice their views at a weekly meeting or at special meetings held to deal with matters that might arise suddenly. We couldn’t rely on being spoken for. We established our own voice and took actions on our own behalf. We held open days in which we invited the public to visit our homes in order to see the improvements, something other than temporary crash pads.

I said to Piers, ‘We could invite the Queen to come. You could escort her around once again.’

We showed off our photographic counter exhibition to the balsa wood model commissioned by the GLC to show their plans for the avenue. Ours was was not as fancy but less lightweight. Local papers reporting on our ‘best kept squat’ printed photos of the winner, a little girl who ‘the GLC want to evict.

This was a microcosm of a participatory, pluralistic democracy. An example of what people can do if left to their own devices.

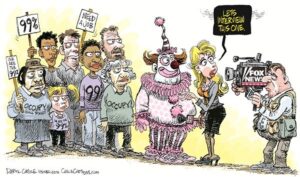

We put great store on a positive representation of us in the media and in the wider society. In lobbying for stronger measures against squatting, private property owners tried to feed us to the yellow press which focused on grabbing people’s attention rather than conveying well-reported news .

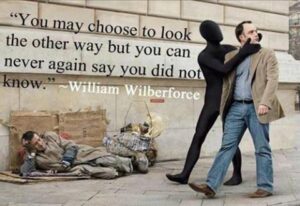

The hyenic media carved effigies which proliferated as the stuff of home owners’ nightmares. They stirred up feelings against squatters, portraying them as being uninvited lice ridden vermin darkening their doorstep, workshy dossers, posh trustafarians, club wielding scroungers bent on destroying ‘law and order’, ‘crusties’ out to create a dysfunctional medieval wasteland by challenging the right to exclusive possession, abolishing sacred property rights , ‘smash and grab’ serial thieves who wouldn’t skip a beat to steal houses of people slipping out to the corner shop. In their narrative an owner could come home from a holiday only to find a cuckoo taken over the nest. In this powerful and cruel myth swarms of Hell’s Angels swamped people’s homes while they were away for the weekend, changing their locks and inviting the local drug lord round for tea. One of the media stock headlines was that ‘a man must once again be king of his castle.’

‘What made this country great was a place for everyone and everyone in his place-and this is my place,’ they quoted a rachmanite rentier in front of one of his reclaimed possessions.’ He had paled at the sight of the poor squatter being dragged out . Not at his predicament but at his cincture. The dude being evicted was keeping his pants up not with a belt but a tie. ‘I say,’ he spluttered, ‘that’s my club tie he’s wearing!’

What the the tabloids deliberately omitted was the fact that the small number of privately owned squats had usually been empty for even longer than council stock, and were in advanced states of disrepair.

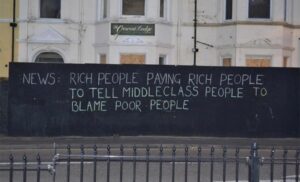

Whipping up this moral panic, the stereotypes focussed on the homeless, blaming them as individually blameworthy. obscuring the inequalities created by the capitalist market.

Blaming those who face the brunt of these inequalities is central to the strategy of those who defend this market.Those who cannot find jobs are held responsible for unemployment. Those who don’t perform well at school are responsible for this outcome as they lack the necessary intelligence and drive to do better. And it blames us all again and again for the pollution and ecological devastation that have been imposed on the population without our consent and often against our will.

They portray the people as innately greedy, selfish and complicit in this. By doing so they place mankind in opposition to nature.