‘The Czech question is either a world question or it is no question at all.’

Thomas Masaryk

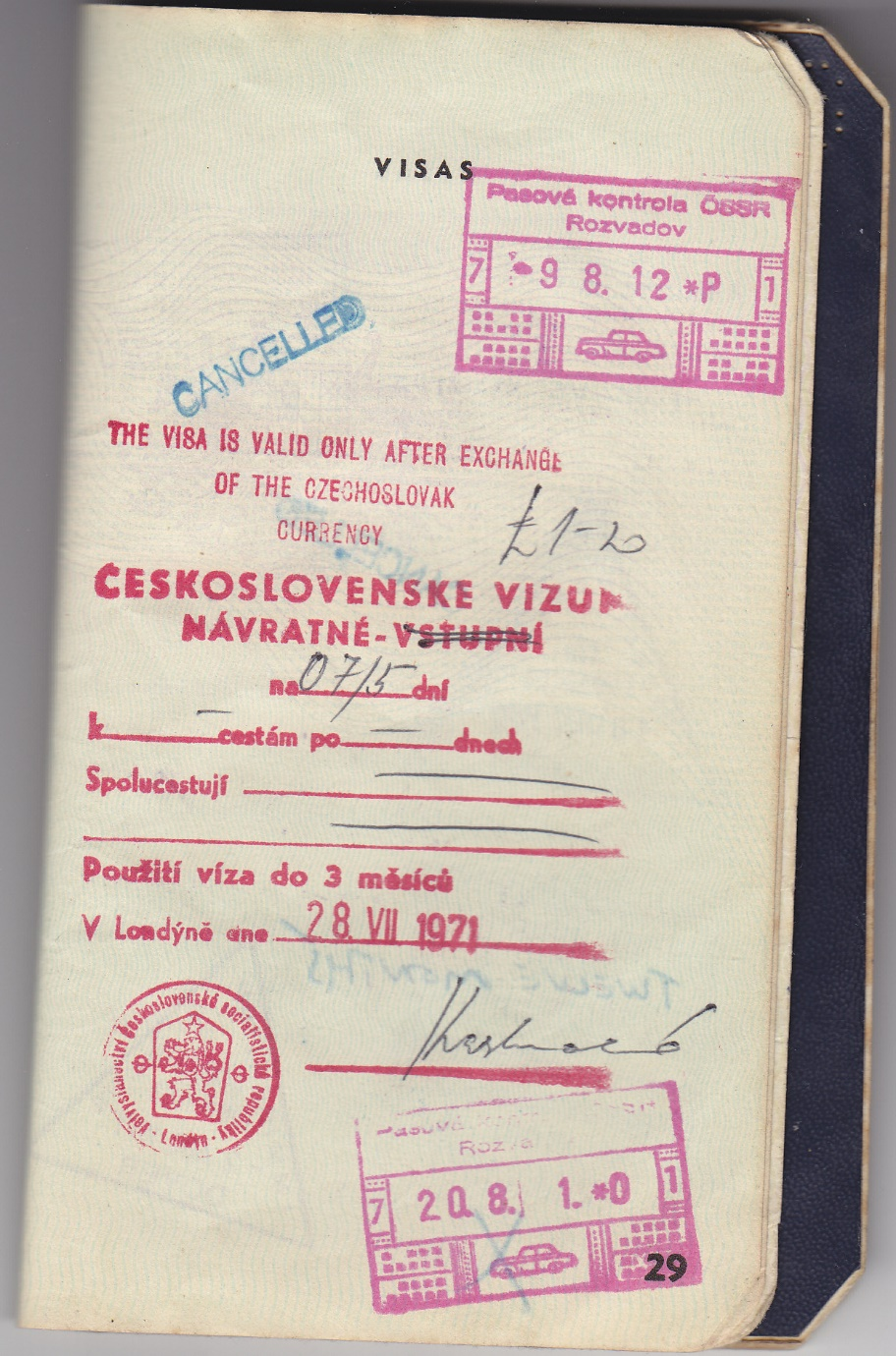

I bought a beat up Singer convertible and drove it to Prague, the Czech shining citadel.

After entering the country I pulled over as soon as I saw him raise his hand and gesture at my car. A young student in jeans, he was trudging along the shoulder of of the road.

After entering the country I pulled over as soon as I saw him raise his hand and gesture at my car. A young student in jeans, he was trudging along the shoulder of of the road.

Appreciative of all those who had ever stopped for me so many times, I was only too happy to be in the position to stop and repay such favours.

‘Where are you making for?’

‘I’m heading to Prague’.

‘What lush picturesque countryside you have.’ I said.

‘Why, thank you-and for picking me up,’ he said, his English colourful yet as good as gold. ‘There’s not much through traffic here so close to the border. You have no idea how long I waited,’ he said. ‘My patience had blasted well slowed to a trickle.’

He picked up on the slight but persistent wobbling and shaking of the wheels. ‘Your car is not properly attired. It looks like it has been maligned in the past.’

My decision to give him a lift paid dividends. He not only could get through to me but was willing and able to recite the episode of the Prague Spring and to give me his thoughts on the current mood.

‘After the cold snap we entered an era of fear and stony silence.

The majority of citizens have fallen silent. They pretend to work. The government pretends to pay them. Cowardice has slowly become a rule of life. Those who wish to get ahead do so by sacrificing others. They accept everything. After they crushed our reform movement in ‘68 the hardliners initiated a harsh backlash which you will feel here. Obedience to the Soviet Union is mandatory for those wind up dolls who govern. There has been in many ways a return to the dark days before.’

‘What was it like before?’ I asked.

‘It’s been bad ever since the Communist led government engineered their 1948 coup.’

‘I saw Costa Gavras’ film, ‘The Confession’ recently. It captures the relentlessly tense atmosphere of the show trials . If the trials hadn’t actually happened, one would guess they had been adapted from the works of Kafka.

The images of this terrible chapter set during are still in my mind.’

‘It will come as no surprise to you that it hasn’t been released here. It reveals the corrupt nature of politicized investigations and the manipulation of “truth” by those in power.

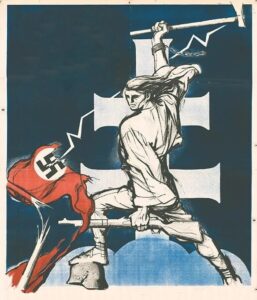

The Soviets have no respect for democracy’s ground rules. The corrupt nature of their politicized investigations and their manipulation of “truth” keeps them in power. We welcomed them on the liberation from the Nazis.

However they’ve long outstayed their welcome.’

‘Some cause happiness wherever they go’, I said, ‘others whenever they go. How have they justified staying on so long?’

‘They argue their model of economic management is superior to those of capitalism but we don’t buy that. They say without them the country would be reduced to unemployment, corruption and chaos. We reject that.’

‘Wouldn’t it be a mistake to see see the mastery of those directing the command economy replaced by the mastery of those directing an economy which rewards their privileged ownership?’

‘We want to be free to make our own mistakes. There is no people on earth who would not prefer their own bad government to the “good” government of an alien power.’

‘So how did they demonstrate the superiority of their form of rule after 1948?’

‘Their local agents set out arresting people all over the country without cause, charging them with subversion, forcing them to confess and say what they wanted. Their families were intimidated to give evidence against them.

In this hall of mirrors nothing was true except what was decided on high. The people they tormented were not really spies or counter-revolutionaries. The problem for their accusers, though was that they were considered unreliable and couldn’t be trusted . “They’re innocent right now,” was the view of the accusers. “But they’ll be guilty later on.”

Those targeted were hauled before public tribunals with the intention of influencing public opinion, rather than of ensuring justice.

They were denied a proper defence.

The prosecution could accuse them of the most ludicrous, outrageous crimes.

They branded them as traitors, throwing them into prison.

Once they were in there it was impossible to appeal.

‘The first wave of purged real or perceived political enemies ended up in harsh forced labour camps.’

‘It appears to me that nobody was above being treated like this.’

‘That is so. Even those with impeccable Communist credentials were not spared. Take Gustav Husak, our current Secretary of the Party, one of the leaders of the 1944 Slovak National Uprising against Nazi Germany and it’s puppet government.

He fell victim to the Stalinist purge of the party leadership and sentenced to life imprisonment.’

‘So you didn’t have to commit any crimes to warrant such punishment?’

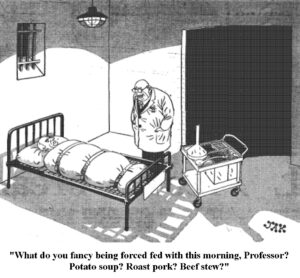

‘A mere positive mention of anything Western could send one to ruin, prison and total ostracism. Or you could be put in a psychiatric institution. A prison for those declared insane.’

‘You know how I view insanity: a perfectly rational adjustment to the insane world.’

‘Well this neurotic pursuit of sanity was driving us all crazy. The official thinking was if you don’t like our superior government, you must be insane.’

‘I do not like thee, Doctor Fell, the reason why, I cannot tell’.

‘Doctor Who?’

‘Oh it’s just an old nursery rhyme. How did people cope with such a grim time?’

They had no alternative but to hang on and even take jokes about it to their logical extreme.’

‘Can you tell me one of these jokes?’ I asked. ‘I believe they usually start the same way.’

‘Yes, By looking over your shoulder. Here’s a well known one. ‘Two policemen were on their beat when they spotted a guy next to the local Party headquarters holding a paintbrush. On the wall, he’d just written ‘The government is run by idiots!’ The first policeman pulled out a pair of handcuffs and asked the second, “Shall we arrest him for vandalizing public property, or for divulging a state secret?’

‘Here’s another: ‘One political prisoner asked another: ‘How long is your sentence?’

‘Longer than I care to remember,’ he replies. ‘Twenty years in fact’.

‘What did you do?’ the first asks.

‘Nothing’, the second replies.

‘Oh come on, tell the truth,’ the first demands, ‘everyone knows for doing nothing you only get ten years.’

Later in an unguarded moment he was caught telling a joke about the Party which led to his appeal being denied’.

The presiding judge responsible for this travesty walked out of his chambers laughing his head off. These salvos of deep rasping inhalations brought to mind an asthmatic walrus. A colleague approached him and asked why he was laughing.’ I just heard the funniest joke in the world!’

“Well, go ahead, tell me!” said the other judge.

‘I can’t – I just gave someone twenty years for it!’

‘And none of such abuses went reported?’

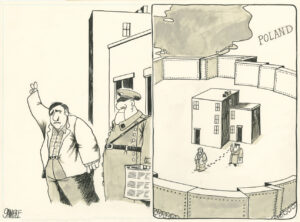

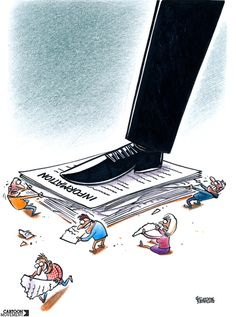

‘They instituted strict censorship over everything. Even in science the scientific process was distorted as a way to reach a predetermined conclusion as dictated by tendentious Stalinist ideology. Commonsense plans were rejected on the grounds that they worked in practice, not theory. They closed the borders to us. No one could complain.

One scientific writer, the manipulation of science wearing on him, applied for an exit visa to emigrate to Britain.

On the orders of hardline President Novotny, the police came to interview him, wanting to know his reasons.

‘Why do you want to leave our country that nurtured you? The pace of life here too slow for you. Let me remind you when you walk on thin ice you’ll have to go faster.

Isn’t your very respectable salary high enough?’

‘Oh, I can’t complain.’

‘Is your work here such a bed of nails ?’

‘ I could do worse than that.’

‘Isn’t your subsidised apartment, free schooling for your children and health service good enough?’

‘ Again I can’t complain.’

‘Then why do you want to go to Britain?’

‘So I can complain. What about you, Inspector, do you yourself ever complain?

‘I have nothing to complain about either.’

‘But you presumably don’t do much writing .’

‘That’s why I have nothing to complain about.’

When he finally settled down in Britain, he took out a picture of Novotny. A friend who was intrigued asked, ‘Why do you carry that with you?’

‘Well, when I miss my country, I take it out, look at it and stop missing my country.’

‘What was the end result of all this repressed discontent?’ I asked.

‘We slipped into a situation where little by little we lost our individual freedoms. The secret police could follow you. They hid electronic devices to listen in to conversations.

Informers could provide them with intimate details of your private life. They could hold this kompromat over you. One of my neighbours even had her bedroom bugged. She was very much a recluse.’

‘Maybe they listened to her talking in her sleep. About the class enemy.’

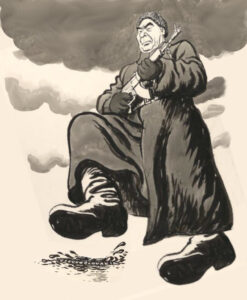

‘These ‘protectors of the people’ monitored our every movement. You could see them at their windows, small mildewed minds looking for little things they thought others might miss.’

‘Every bowel movement by the sound of it.’

‘It was like a disease. One over zealous man who wrote to them regularly exposing ‘undesirables’ and ‘detriments to the dignity of the state’ even informed on himself. In a society where you know that you are being watched, eventually you will watch yourself, and save the authorities the trouble. Our country became enfolded in a curtain twitching Kafkaesque depression. They could call on you at any time.

They could invite, “Come as you are. Just the clothes you’re in plus your papers”.’

’So how would you compare the clampdown now compared to before?’ I asked.

‘Today’s regime is not a complete return to the heavy-handed Stalinism that prevailed during the first 20 years of Communist rule in the country. It’s not as violent-no more being picked up on the street, no more dull panting of motors rumbling outside your house at ungodly hours, your house being taken apart – it’s more subtle, more pervasive and intelligent. Agents packed-up in black leather jackets can knock on your doorstep dropping hints. Their bosses can let it drop-‘accidentally’ of course-that you’re sleeping with your friend’s spouses or that you’re a pedophile. Your family could end up not getting a place at university.’

’‘Just how aggressive was their questioning technique ?’

‘Their interrogation technique wasn’t really about asking questions. It was more of a rhetoric. When you install the answer inside the question, you don’t really let the other person choose his own answer. For example, they said something like, “As someone who justifies and legitimizes the attacks by the West against our socialist motherland, don’t you think that…” — you know, that was their technique.’

‘You don’t mess with the intelligence agency here, there or anywhere’, I said. ‘That’s my conclusion’.

‘Because of it’s very size here, it’s sometimes slow to awaken. Like Cerberus, the monster guard dog of Hades, put to sleep by Orpheus. If you walk by it, it may lift an eyelid and sniff at you. But if you awaken it—‘

‘Heaven help you. Let sleeping guard dogs lie.’

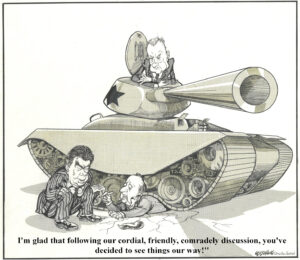

‘The regime kicked hundreds of thousands out of the party and their jobs. All the problems from before it ignores and marginalises. It has offered us a new social compact: ‘You don’t meddle in politics. You go along with us and the world will take care of itself. You’re entitled to your opinions-just keep them to yourself. You got to work, you do your job, you go home. That’s all. You leave politics to us. As long as you retreat into privacy and mind your own business, you’ll be O. K.’ . This is an offer we can’t refuse.’

‘It sounds familiar’, I said. ‘Total contempt for democratic ideals.’

‘It restrains you from sharing your thoughts with others.It led us to adopt the following self-regulating precepts: ‘Don’t think. If you think, then don’t speak.

If you think and speak, then don’t write.

If you think, speak and write, then don’t sign.

If you think, speak, write and sign, then don’t be surprised.’

‘Talk about the Prague Spring.’

‘Dubcek and his reformist faction wagered that without reform within the socialist framework, the Party would remain unpopular and despised by the majority of the people. To really renew it as a legitimate vanguard leading society. They brought in sweeping liberalising changes, an important break with the Stalinist period. They were basically saying to the people, without saying it literally: ‘We’re sorry. We’re going to give the country back to you.’ This meant lifting one of the party’s sensitive policies-censorship. The question arose how far people could go in voicing their opinions about the thaw.

In Moscow things were seen rather differently.’

I saw the evidence of this Wenceslas Square. I was nearly arrested there. A police officer claimed I was photographing a military subject. I was. They were bullet holes still intact, riddling the façade of The National Museum, one of the backdrops to the invasion.

Soldiers in tanks had confusedly showered the Neo-Renaissance building with machine gun fire.

The shots had made numerous holes in the sandstone columns and plaster, damaged stone statues and reliefs, most of which remained visible.

The museum remained a potent symbol of the occupation. It wouldn’t have been the Czechoslovak nation if, even in such an event, the people didn’t manage to find a spark of humour. People nicknamed the damaged façade: “the mosaic by El Grechko” after the Soviet Defence Marshal.

I followed the policeman’s directive, moved on and reported this back to Jan.

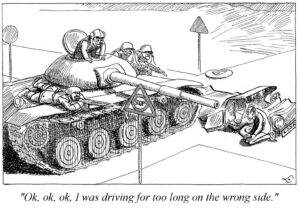

‘At the time,’ he explained, ‘the hardliners felt they would lose control and we’d send them on their way. Just before midnight on August 20 I was awoken about midnight. People were crying out: ‘The Russians are here!’

I was terribly afraid. Once inside the capital Soviet forces took up positions in front of government buildings including the offices of Czechoslovak public radio. When I was crossing the street here the soldiers were sitting on their tanks with their machine guns. They were aiming and shooting at us. That didn’t stop us in the following days and weeks pouring into the streets in our thousands.

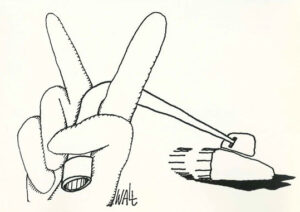

As you know we learn Russian since fourth grade in elementary school. We carried out pranks of changing street names and road signs, of pretending not to understand Russian, and of putting out a great variety of humorous welcoming posters. When things got serious we accosted the soldiers, telling them ‘Go home! Natasha is waiting for you.’ Some of us jumped on the tanks haranguing the soldiers. Some threw insults at them.

Others went to the point of ramming rags into the tanks’ exhaust pipes and lighting them. What more could we do? All resistance was steamrolled. The liberalizing and pro-democracy movement initiated by Dubcek was smashed.’

‘We know he was forced to resign his post.’

Yes, this was an example to the whole country not to overstep the bounds set by the hardliners.’

‘Was that the end of the protests altogether?’

‘The political ideals of the Prague Spring were slowly but steadily replaced by the politics of accommodation to the demands of the Soviet Union.’

‘What about the role of Husak?’

‘He was originally Dubček’s ally. He is a pragmatist and called for caution when he witnessed the response of the USSR to the reforms. He reversed them, purged the party of its liberal members and remained loyal to the central organs of the Czechoslovak Communist party.’

‘How has he managed to get away with this?’

‘He has managed to appease our outraged civil population by providing a relatively satisfactory living standard. There’s a joke about him that goes as follows: Two friends are walking down the street. One asks the other: “What do you think of Husak?’

‘I can’t tell you here,’ he replies. ‘Follow me.’ They disappear down a side street.

‘Now tell me what you think of Husak,’ says the friend.

‘No, not here,’ says the other, leading him into the hallway of an apartment block. ‘OK here then.’

‘No, not here. It’s not safe.’ They walk down the stairs into the deserted basement of the building. ‘OK, now you can tell me what you think of our Party Secretary.’

‘Well,’ says the other, looking around nervously, ‘actually, I quite like him.’

‘He was wise to implement moderate reforms and not to go too hard on critics,’ I said.

‘Husak has avoided any overt reprisals[ as was the case in the 1950s. A number of political prisoners have been released though how free are they when they can’t leave the country.

He is allowing those who were purged in the aftermath of the Prague Spring to rejoin the party. However, they are required to publicly distance themselves from their past support for reform.’

‘So there’s nothing happening in the street to protest this situation?’

‘Nothing of the kind, I’m afraid. However there was a short lived series of protests that took place in response to Czechoslovakia defeating the Soviet Union in the 1969 World Ice Hockey Championships. In response Brezhnev tightened the hardliners grip even more securely, tying down Dubcek even more.’

What do you think Marx would have thought about this abuse of power, Jan?’

‘I feel sure he would have been full of contempt for people like Brezhnev.’

‘Do you think such a period of economic and political liberalization will come again any time soon?’ I asked Jan.

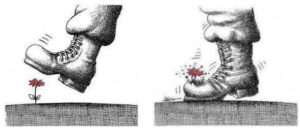

‘Eventually. You can crush all the flowers but you cannot keep spring from coming .’

Jan offered to put me up at his family home in Prague. When we arrived his mother served me some schnitzel. We used to call the good stuff way back the ‘Emperor’s Schnitzel.’ We call this one the ‘Proletarian’, she told me. It’s been decorated by the state. A hero schnitzel-made of granite. Awarded for it’s toughness.’

I noticed she had a bloodstain on her apron’’

‘You had a hard job cutting that meat?’

‘You can’t get blood from a stone. For a long time I haven’t seen anything fresh enough to bleed. That spot is from my finger. My knife slipped while I was trying to cut this schnitzel.’

I found out the bread she selected from the bakery shelf was stale and also extremely hard to cut through.

Sitting in the corner chair at the table for breakfast, I felt a thick bulge under my foot. There was a wad of paper stashed under the carpet. Bringing this to Jan’s attention, He pulled out two slim volumes explaining:

‘Any critical writing is forbidden here.

Concerned writers have to publish on the quiet. This is how they reach us. By samizdat.’

‘I’ve heard of gosizdat, the Russian state publishing department. How does samizdat differ?’

‘Samizdat’ is a play on this official abbreviation. It means ‘I publish myself’.

‘Izdat write’? I quipped.

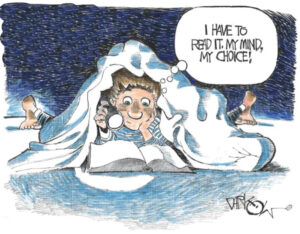

‘It’s publishing of a kind. It’s a way of making information and literature available for the public to view when you’re not allowed to publish. The techniques are primitive. Take this book for example,’ he said, handing me one of the two.’ It was made on a typewriter. From there, by the law of samizdat, it was handed on to people, some of whom would have typed up their own versions and passed them surreptitiously to friends, and some of them would have done the same. Thus can a book shuffled from hand to hand in a chain of delivery reach hundreds and, perhaps, even thousands of readers. In exponential progression.

‘Like rabbits,’ I said. ‘How is it made possible?’.

‘Through the technological magic of carbon paper. Each time someone types a single page of a future samizdat book, he or she is actually creating anywhere from five to ten copies at once. The carbon copies are bound together. Then other people who want to read them either buy a few copies or retype more copies.’

How do they differ from official publications? I asked.

‘Make no bones about it,’ he said, handing it to me, the first pages open, ‘this one is an original, the letters are crisp and clean, with no distortion whatsoever. With this other one’, he said, rustling through the pages, ‘the typescript is rudimentary, words crammed to the edge of the page, scribbled with edits and uncorrected errors. The overtypes in the carbon copy are invariably a mess of ink that leaves you guessing at what the writer actually has in mind. Moreover with this one-a novel- it’s only a portion. No one has a complete copy of the text at one time.’

‘That’s a pity,’ I said.

‘That being said, such books are a good conversation piece. People meet and put their heads together to work out what really happens in the story. They are so well researched and informative that the public devours them in the manner of best sellers.’

‘I gather the writer here is held in the highest esteem. They must be very well educated,’ I suggested.

‘And strong. With muscle and fury to hit the keys hard’.

‘And courageous,’ he added. They can be imprisoned if caught. Then of course we readers have to hide the books. The consequences of being caught with them are harsh’.

‘Are they popular? I asked.

‘You’d be surprised who reads them. Even children do.

There is a joke that testifies to their popularity. A Party V.I.P. asked his secretary to type ‘The Good Soldier Schweik’ for his daughter.

‘For heavens sake, why?’ she asked. ‘The book is on your library shelf. It’s perfectly legible, you can read it in print.

‘The book is on your library shelf. It’s perfectly legible, you can read it in print.

‘She has to read this novel for school but she doesn’t read anything but samizdat,’ he replied. ‘She won’t read anything unless it’s been typed.’