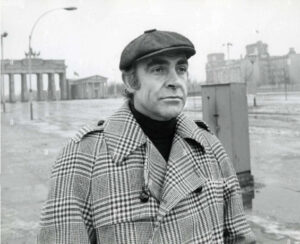

One of my first outings in Berlin was to inspect the Brandenburg Gate, this iconic potent symbol of Berlin’s division. It was situated right at the border between East and West Berlin, just inside the death strip.

From the western side I mounted a viewing platform, constructed so that western spectators could take a squiz over the wall into the east.

Atop the gate could just make out the back side of the Quadriga, a chariot drawn by four horses driven by Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory.

Berlin’s symbol as a place of both truculent militarism and enlightened idealism. The iron fist of rule and the velvet gloved hand of elegant ideas. The tussle over its adornments mirrored those of the authorities competing for power.

After being wrested back from Napoleon, the wreath of oak leaves, conceived as a symbol of peace, was supplemented with a new symbol of Prussian power, the Iron Cross, changing the figure’s interpretation from a courier of peace into a goddess of victory. The Cross wasn’t there during my stay, having been removed by the East Berlin authorities, deeming it an inappropriate symbol of Prussian militarism.

Instead, they displayed their own on the flagpole behind it. The something I could just about make out in the middle of the flag. The hammer and compass emblem of the German Democratic Republic.

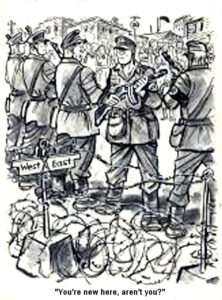

There was no crossing point here – indeed, the wall was particularly thick at this point, in case of any attempted attack by tanks. To view it as it faced the other direction, I had to go to some length via a slightly unassuming street, actually one of the most iconic locations of divided Berlin – Checkpoint Charlie.

The desolate Pariser Platz leading up to the gate on the eastern side was designated part of the border defences, so even walking up to the gate was impossible except for V.I.P.s.

This visitor standing there is facing the same direction as the Quadriga.

While West Berlin was for most the main attraction, I was more interested in what was going on in the East. Over there, da drüben, looking to steal away their forbidden fruit, I was more a rare commodity, as rare as a choice sweet banana.

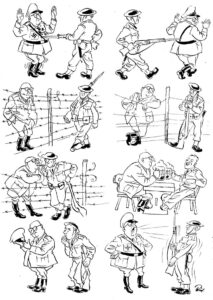

Some of the border crossing customs officers were gruff and stern while some had a good sense of humour. One who recognised me as a regular crosser issued me the following warning, ‘Make sure you’re back by midnight before your day pass expires- or else.’

‘Or else what?’I queried.

‘Or else you’ll turn into a pumpkin.’

Official coldness still being off-putting to many visitors, I found it easy to meet young people during the thaw that had set in. The Socialist Unity Party whose organs formed the skeletal structure that the entire state was based on, which reached into every corner of society whether it be schools, factories or residential areas, had relaxed it’s vice-like grip.

While they had made a lasting impression, the heavy stalinist days had long gone when one could be pulled off the street, when a phone call or a knock on the door in the dead of the night could lead to one being bundled out of one’s home like a common criminal and spirited away to some undisclosed destination. To the forfeiture of both public and civil rights as well as property. One joke told to me had a policeman having a confidential chat with his closest friend: ‘Wilhelm, what do you really think about Ulbricht?’

Wilhelm replied cautiously, ‘Franz, I think about the Chairman exactly the same way as you.’

Franz replied: ‘Well, in that case I’m afraid I’ll have to arrest you.’

Now was a period of petty strictures and impediments to serious dissent. Sounds familiar, you might say.

We can compare them to those imposed by the Western establishment where those it favours hold or control public powers in the state and institutions such as education.

These restrictions caused much dissatisfaction even among some members. One asked another, ‘Comrade Schmitt, why weren’t you present at the last meeting of the Party?’

‘No one told me it was the last one. If I’d known that I’d have brought my whole family.’

‘Now’ was also a period of relative stability, social modernization and ‘consumer socialism’. Wages and pensions had been increased, paid holidays were extended, consumer goods became more available. Thanks partly to me.

In general, East Germans wore ersatz clothes that had gone out of fashion ten years earlier in the West. My friends there would have been some of the most comfortably dressed as I regularly wore two pairs of blue jeans there – just one coming back. The local ones looked as if they’d been made in an unsuccessful Soviet tractor factory.

At the same time my friends were protected from the affluenza that was prevalent in the West-the social condition where too much is never enough.

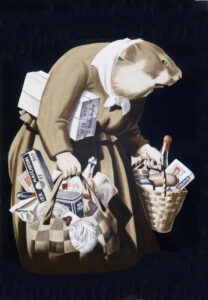

Carrying cigarettes, alcohol, chocolate and west marks, I was a travelling minimart. Smuggling goods and money exchanged on the black market were practices the Wall was intended to prevent. Before its construction many border crossers were living in the East but working in West Berlin. Because of the exchange rates, they were earning four or five times as much as West Berlin workers. They were reaping the benefits of the socialist state without paying a penny in taxes to it.

Yes, there were drab grey streets filled with houses in decay, gigantic, dreary, monotonous satellite settlements of brutalist unclad concrete tower blocks rising up on the outskirts. Outside, the smell of sulphur. Inside, through the inner courtyards and stairwells, the décor gaudy utilitarian. As for me, I lapped up the great number of surviving pre-war facades and old-world streetscapes, free from commercial signage, that hadn’t been given the cosmetic makeover. The whole country needed a paint job.

That was part of its charm. Crumbling buildings with masonry still peppered with the bullet holes from the closing moments of the Third Reich. Noirish downtown streets rain-streaked and lit, at night, by dim flickering lamps that reflect off the slick cobblestones and metal street-car rails, cloak and dagger drags where you might expect Harry Lime or Alec Leamas, collar flipped up, shoulders hunched, to appear in a dark passageway.

Better still in a midnight rendezvous, Lola to step out from ‘The Blue Angel’ to read my lips.

Or at the very least Bond to appear beside some classical statue watching out surreptitiously .

Was it for for his eastern bloc counterpart?

The suburban streets were free of traffic din, save for the put-putting like lawnmowers. The whir was conspicuous in the otherwise silent streets. Shutting my ears, I could have been back home in a bush town on a Sunday morning. Opening them I would have seen the odd Trabi, the legendary rinky-dink rattletrap with the clattering two-stroke motor, hurrying and scurrying about.

In the East the buildings and their surrounds were kept as clean as those I kept in the West. The residents took turns to clean the steps, cellars and sidewalks. During spring cleaning waste was removed, trees and shrubs were planted, often by voluntary labour.

One Russian resident of the DDR, a Mrs. Vladimir Putin, would recall the same observation as mine: “The streets were clean. They would wash their windows once a week.’

I made friends at rock music venues, a scene reflecting the zig zag policies of the regime-varying degrees of lassitude interspersed with twinges of kneejerk moral panic. its recurring error was to see lifestyle non-conformity as a political challenge when it really wasn’t.

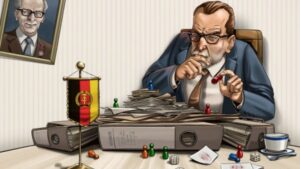

Fuddy duddy functionaries obsessed with stamping out what they deemed anti-social behaviour. In dealing with louts and hooligans, the political police were actually quite popular. There was high degree of participation in cooperating as “unofficial helpers” of the Stasi.

Not that any of this concerned my friends Renate Foerster her brother, Wolf from number 2, Glatzerstrasse, and her friend Kiki Klebowski. They had no reservations courting links with unknown quantities like myself. Like young people everywhere these East Germans just liked to have fun and were able to find private happiness and satisfaction beyond great ideological demands. Life wasn’t too stressful. It was frugal but secure.

GDR kindergartens didn’t cost parents anything, and provided free meals for children.

They held a job for a lifetime and would receive a steady pension when they retired at 60. Unencumbered, encouraged but not coerced into joining officially sanctioned organizations, showing ritualistic support when necessary. Allowed more independent agency than outside critics of the system give it credit for, they faced typical youth challenges such as friendship and love rather than great ideological demands of the state. They created a space for their private life.’

‘I can understand the authorities wanting to keep young people disciplined. Is it difficult to find a good party here?’ I asked.

‘In West Berlin, you can always find a party. Here the Party can always find you!’

As for their oldies, I found that left alone, they spent much of their free time in Balkonia. Rather than any Ruritanian retreat, this turned out to be nowhere more distant than the private niche of their apartment balcony. These were people with their own lives and goals rather than as a matter of course the Western portrait of poverty-stricken, oppressed folks with only escape on their minds.

Knocking about with their youth, I became familiar with the economic situation faced by the majority of East Germans. On the plus side prices for necessities such as staple foods and clothes were kept artificially low by the government.

An appreciable minority of people owned their own houses and some built their own privately. Most lived in rented accommodation at controlled and affordable rents. Because the vast majority of the country’s housing stock was built in the pre-war era, often at the turn of the century, the building administration [KWV] had to consider which were salvageable.

Likewise many factories and workshops were run down and obsolete.

At the same time factories and schools provided exercise breaks for workers and students.

Rents remained virtually unchanged over the life of the GDR and no-one could be evicted from their home. There was therefore little homelessness or fear of becoming homeless.

Then there was astonishing cultural provision – It wasn’t just that there was an abundance of cultural offerings, but that the appreciation of culture clearly had mass appeal. The art galleries were always busy, and the Brecht production I attended was absolutely packed. And not just with the kind of people you might have expected to see in the West, where such things tend to be perceived as middle-class pursuits. In the GDR there was nothing elitist about going to a classical concert or opera: it was simply something enjoyable and stimulating that was accessible to all.

Theatres and cinemas were heavily subsidized. People would often start queuing for concert tickets before dawn, even in the depths of winter, in order to be sure of getting them. Even though the opera tickets were still fairly pricey in relation to average wages, they bore no resemblance to the obscene prices charged in the West. Other cultural events were truly affordable for all. Life in the DDR was enormously enriched by it.

Everyone could use world class sporting facilities. This was very successful. So much so that it gave rise to the famous joke headline: ‘East German pole vaulting champion has just become the West German pole vaulting champion.’

I may well have met one of his ilk. At a track and field meet of Warsaw Pact countries I chatted with an athlete carrying an eight-foot-long metal pole. To test his English I asked him, ‘Are you a pole vaulter?’

‘No,’ he replied, ‘I’m German. But how did you know my name is Walter?’

‘Just a guess, Walter. Now some guess that athletes in the GDR are supplied with drugs. They call for drug testing. Do you believe in this?’

‘I believed in drug testing a long time ago. Preferably the multiple choice kind. Over the years I’ve tested everything.’

Whatever enabled their performances, the East Germans kept breaking records in track and field.

‘Was it something in the water?’ I wondered.

Public transport was basic but cheap. It got me from A to B efficiently. I was fascinated by the honour system for payment on transport. I got on a train, I put the fare in the box. No need for ticket collectors. It freed up labour. On the other hand, goods were more often than not shoddy, badly handled and wore out in a jiffy. The plain, cheaply-made currency itself was derided as stage money. This was all a sore point for Germans who pride themselves on their technical expertise and saw their efforts compared unfavourably with their Western cousins.

I bought a watch which went on the blink after a month. I reported this to a friend who told me the following joke:

‘Three DDR citizens are sitting in a prison cell and talking about why they have been pulled in for interrogation. The first says, “My watch always went ahead, and I would arrive too early to work so they said I was spying.”

The second says, “My watch was always behind, I always came too late, so they said I was engaged in sabotage.

The third said, “My watch always worked perfectly, I always arrived on time, so they said my watch must have come from the West.”

This shoddiness was obviously put down by critics to guarantees of employment by the state and lack of competition, leading to a lack of responsibility, bringing out leisureliness and laziness in some. Moreover, all goods and services that were not necessities were thin on the ground. This necessitated a time-consuming searching and waiting in line for “luxury” products such as tropical fruits. It was Time for a a new national anthem based on honesty, I thought: ‘O yes, we have no bananas.’

The delivery time for a Trabant 601, the cheapest car made in the GDR lay between 13 and 15 years.

‘What does the ‘601’ in Trabant 601 stand for?’ I asked Wolf Foerster.

‘ 600 people will order one, but only one will get it delivered,’ he answered.

This rugged compact vehicle looked like a cross between a golf cart and an amusement park bumper car. ‘You have to step outside to shift gears,’ I wrote home. ‘You don’t drive it. You mail it. In the water, it becomes an outboard motor.’

The story went about a customer who ordered one. The salesman told him to come back to pick it up on November 7, in fourteen year’s time. The customer asked: ‘Shall I come back in the morning or in the evening then?’

The seller replied: ‘You’re joking, aren’t you.’

The customer said, ‘No, not at all. It’s just that I need to know. The plumber’s coming at 3pm.’

Then again there was no autobahn carnage.

Not that Honecker was setting the right example, demonstrating the benefits of walking and an efficient public transport system. His main vice as regards corrupt luxury was automobiles. He had accumulated a fleet of cars including a Soviet Chaika, two Land Rovers, and two Mercedes 280s.

This bad example crossed over into the joke about his driving them. One day Honecker stepped out of his office to run some personal errands. He thought his chauffeur was going too slow and urged him several times to hurry up. But there was a big traffic jam and Honecker remained frustrated. Finally, he took control of the wheel by force, pushed the driver into the back seat and drove the Mercedes himself. He wove in and out of the traffic creating great chaos. A policeman called the head of traffic control to report the situation. The head angrily questioned the traffic cop on the scene: ‘Did you get a good look at this troublemaker?’

‘Yes, I did to be sure.’

‘So why didn’t you arrest him?

‘I didn’t dare. He’s a very high official.’

‘How high?’

‘I don’t know. But I can tell you this much – Comrade Honecker was his driver.’

Whatever homes I went to, things inside looked very much the same. I was already familiar with the contents. People only had one or two kinds of each product. They all had the same laundry detergent, the same deodorant, the same scales at home. That was unless they had Western currency and were able to shop at Intershop. Then their home had a bit more variety. But in general, they had one or two varieties of a product, and they had to make the best of it. On the positive side, this avoided the wasteful duplication of the capitalist economy.

Many people had allotments where they grew their own fruit and vegetables; or if they weren’t gardeners, they were good at ‘do it yourself’ and could repay the favour of a few kilos of soft fruits in the summer by being willing to fix a neighbour’s dodgy plumbing. This was partly because of the poor supply situation and partly, too, because of the interminable bureaucracy.

DDR life was eased considerably if you had “Vitamin B”, where the B stood for Beziehungen- Contacts. But such contacts take time to build up. To move up you had to have heavy contact. It was important to know the right people. Private connections to producers and political decision-makers were often more important than crossing their palms in order to be able to purchase rare goods.

While socially life with friends and neighbours was close, it was otherwise restricted and controlled. ‘I would love to travel to France’, sighed Renate, but I guess I’ll just have to wait.’

From Royal Hunt to Battle Royal.

While travel within the DDR was strictly controlled, having the universal door opener, hard currency, I got approval to make a day return trip to Halbe. My interest in going there was raised by the military liaison officers at my workplace.

The train was typically dated and extremely slow, its carriages tired and worn, but that was fine by me.

Halbe is now forever associated with hunting.

As the train headed into the platform I was awaited by Germany’s first Kaiserbahnhof station.

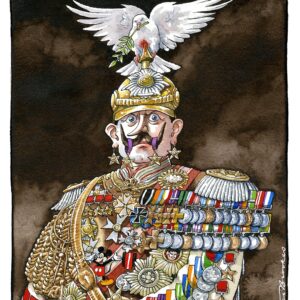

It was built for Kaiser Wilhelm I of the royal Hohenzollern family.

Seriously neglected, but still looking impressive, the bullet pocked structure would have to await the collapse of the DDR to be abandoned then painstakingly restored.

The Royal reception building served as the starting point for the hunts of the emperors in the extensive forests surrounding Halbe. The Kaisers and their families used the private facilities at the station to refresh on their way to their hunting lodge – there were separate entrances and rooms for the Kaiser and his ministers and attendants. They probably only spent fifteen minutes in the building before heading off, but there was always a dinner there on the way home, after they had gone on a massive hunting spree that decimated all the wildlife, probably for several years. There are figures of 560 animals being killed in a single stay at the lodge.

The hunt was quite often the place where important political decisions were made. It was like a boys’ club. The men were together and they felt free to talk about power. They could execute their power in a very direct way by killing living creatures. They also took their sons with them so that they were sure to pass on the flame.

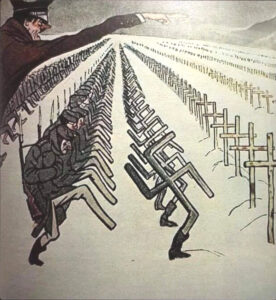

After looking round the station I sought out the huge cemetery outside Halbe. This is the final resting place of many thousands of German bodies.

Some of the earlier ones had been brought back from the battlefields in the East.

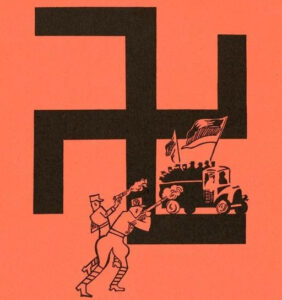

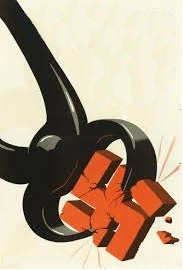

The swastikas on their gravestones were later removed.

Most were from the forces hunted down and decimated by Soviet armies during the march on Berlin.

As well as many Russian fallen, they had been buried in unmarked graves. Tall pine trees stand silently above row upon row of graves, some bearing names and some just listing a number of soldiers and civilians whose remains have been interred beneath the simple plaques.

In the forests around lay and still lie many more victims of the fierce battles of WWII. The numbers of dead and missing are impossible to quantify. Bodies lie at all different depths in the forest, depending on whether they were split apart by bomb shards and lie in the crater or were shot dead or crushed by tanks.

The earth’s structure is completely changed when a bomb has exploded. Some bodies lay or lie just fifty centimetres below the surface of the sandy soil. Others can be one, two or three meters down. After the big bombs went off, the bodies could and can still lie as deep as fifteen metres.

As I made my way along the rows I thought about all the innocents-those military elements reluctantly forced into battle, the civilians caught up in the fray, the refugees fleeing and the children.

What did they have to do with all this horror?

So many children paid for this war with their lives. Really tiny ones, new born, or two or three years old as well as teenage combatants.

Observing one guy squatting down at the foot of a pine furtively scratching at the ground, I realised there was a more recent category of hunting at play. Artefact hunting.

There are some reckless enough to risk the price of death searching for memorabilia and ordnance from the war.

Back at the quiet, peaceful town of Halbe, waiting for my return train, I imagined the scene just twenty five years before. When it rang with the thunder of cannon fire, the distant horizon suddenly turning a fiery red. The rumbling in the distance, the huge bulging clouds of black smoke, the mad scramble for escape.

Entire roads rammed with abandoned vans and trucks, dead soldiers and civilians left and right, some mown down and flattened completely by tanks. Bullets and shells flying every which way, survivors staggering alongside vehicles at a snail’s pace. The call going out from front to back, from vehicle to vehicle: ‘The Russians are Coming! Tank to the fore!’

Suddenly appearing, one of those monsters on chains, pushing ahead past stalled vehicles, grinding the dead on the road right into the dust, civilians in their midst. Dead soldiers lying simply everywhere – in houses themselves, in front yards, on the steps, in the garden, outside the gates stuffed to the very top with the bodies of dead German soldiers to keep those huddled inside in and to keep those outside out.

Arms hanging down limply, overlapping, heads dangling. So many dead, with no one left to bury them, still around far into the fly infested summer after all the shooting stopped, the stench unbearable.

I wondered the fate of those who managed to escape from Halbe.

An Exception to the Rulers

Hans Jochen Scheidler, a fellow francophile and a man to know, was one of the lucky few amongst his generation to have already made it to the City Of Light.

‘Of course’, said Jochen, there’s plenty of lovely places we can go to like Prague, the Dalmatian coast and Lake Balaton. The world doesn’t begin west of the D. D. R.’

‘It’s all relative to where you want to be,’ I said. ‘For a number of English people wogs begin east of Dover.’

‘You can go anywhere but wherever you still have to deal with yourself.’

I knocked around with Jochen, doing the rounds of the smoky clubs with him and his friends, sharing stories of our past and hopes for the future. Patrons partied on hard, but for all their natural enthusiasm, the hardship of their imposed isolation left smiles diminished and eyes averted once the music had stopped.

Clärchens Ballhaus was rather classier, especially in the upstairs chandeliered Mirror Salon room with its fin-de-siècle vibe. Like myself Jochen was fascinated by the epoch immediately preceding our own. On one occasion a recording of Satchmo playing ‘Mack the Knife’ was playing in the background. ‘A great cover of the Brecht-Weill song,’ enthused Jochen. When Louis came to Berlin, I greeted him along with the Tower Jazz Band.

You appreciate such artists more when they are a rare treat. We couldn’t hope to ever see him in America so we had to wait for him to come to us.’

‘If the mountain can’t come to Mohammed, then Mohammed must come to the mountain,’ I said.

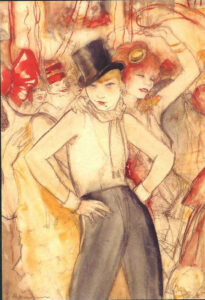

‘Mind you we treasure what we’ve salvaged from our own rich heritage,’ he said, looking around at the beautiful décor surrounding us. ‘See for yourself’, he said, pointing to the high ceilings, the huge cracked mirrors, ornate moulding work and candlelight sconces that transported us straight back to the glamorous café society and the far-ranging cabaret scene of the 1920s.

‘This was a time like no other’, Jochen explained. ‘Freedoms of expression, sexual, political, artistic, all coalesced like never before to make fun of commercial fads, fashions and the extreme politics of the day, showing off a new aesthetic.

‘What was this set of principles?’ I asked.

‘It was a special mixture. It mixed up chanson, raillery and the artistry of the body. Artists sometimes appeared without a stitch. To be seen as avant garde, it seemed all you needed to do was take your clothes off.’

‘Where could you see such performances?’

‘You could see them here and at all the nightly parties, places of supposed respite from the horrors encircling them. Families begging for food, goon squads marching in the streets.

At places like here you were supposed not to think about the sickness closing in. Nevertheless they were always accompanied with a hint of danger. Some likened it to dancing on the edge of a volcano. These events were punctuated by daily dust-ups and deadly ambushes in the street.’

‘It’s incredible how much change, tension, bloodshed, division, but also creativity and freedom could fill one city in such a short space of time’ I said.

‘Berlin defined what it meant to be modern. It was the intellectual fulcrum of a liberal republic’, Jochen continued. ‘People gathered right here to talk about the rich developments in the arts.’

‘Such as?’ I asked.

‘Such as Dadaism, Expressionism and the Bauhaus – and sciences that had their origins here. It was in this scene that Ernst Busch first rose to prominence as an interpreter of political songs.’

‘Who was he?’ I asked.

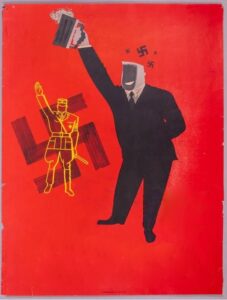

‘Ernst starred in the original 1928 production of Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, until the criminal government applied a chainsaw to this atmosphere of tolerance and many of the great works of art and literature.’

‘Let’s have a toast, ’ I said, ‘to the end of all nationalist and nuclear madness. I drink to you and your health, to the health of your leaders and the health of your people, because if you die, we die. If you survive, we survive. We’re all in this together.’

On one occasion, twilight dimming the sky above, returning to Friedrichstrasse to catch my train, we passed the neo-Baroque Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. “Another treasure saved from the flames,” I said.

‘Let me lift the veil of some it’s delights for you,’ said Jochen. It was just as he said it was. A confection of Wilhelmine frippery, overloaded with columns, arches, statuary, and red plush, the epitome of bourgeois opulence. ‘In this intimate space, behind this gilt-swirled proscenium and its pleasantly zaftig figurehead, is where Brecht’s questing theatre reached its final flowering,’ declared Jochen.

‘Given his austere theories, which insisted that drama ought to be didactic, I expected something more like the auditorium of a high school,’ I said.

‘The brechtian world is full of contradictions and ironies, Allan. Just like the real one. After the War when the city was wallowing in political and economic chaos, the Berliner Ensemble Company, which the theatre housed, gained international kudos for its brilliantly directed political plays. Keep in mind that theatre and politics have a long history of close association in Germany.’

‘It is firm in my mind. I’ve read ‘Mephisto’.

‘The roman a clef. Then you’ll know what I’m talking about. This is a thinly-disguised portrait of one of our principal actors during the Third Reich.’

‘I remember how he ingratiated himself with his mephistophelean minders. All to keep and improve his job and social position.’

‘Have you heard this one about the devil and the actor?’ asked Jochen. Lucifer appears before this narcissistic actor during ‘The Thousand Year Reich’: ‘I have a proposition for you. I’ll satisfy your every wish. I’ll give you Rolls Royces, beautiful women, money to burn. All of these if you sell your soul to me. The actor thought about this for a moment, then asked ‘So what’s the catch?’

‘The Theater am Schiffbauerdamm must hold special memories for the German people.’

‘For me personally as well,’ said Jochen.

‘In what way?’ I enquired.

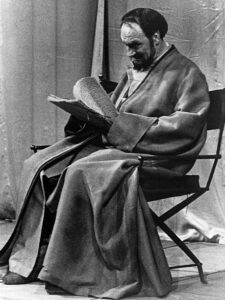

‘I had the good fortune to audition here for Brecht’s hallowed classic “the Life Of Galileo”, a play about the responsibility of the scientist.

I got to be handpicked by the great man himself.’

‘You worked with the venerable Berliner Ensemble. ‘That must have been the chance of a lifetime.’

‘Was it ever. I Worked alongside the likes of Ernst Busch who played the title role.’

‘It must have been challenging working with creative minds of such stature. How did you rise to the occasion?’

‘If you want to walk with giants you must take giant steps. What you have to keep in mind is that these productions were team work , not personal in the bourgeois or individualistic sense”.

‘Laurence Olivier remarked that the Ensemble was more than a theatre, it was “a way of life”,’ I added.

‘It certainly was, Allan. Our troupe went on a European tour at a time when even West Germans faced tight travel restrictions.’

Keen to find out more about this episode, I commented ‘You must have been overawed to be in the presence of this master of drama.’

‘Not really’, Jochen replied, ‘As I have suggested, he was no stuffed shirt – very down to earth, simple, scruffy, unshaven, speaking straight from the shoulder, chomping away on his fat cigar, not bothering to keep up appearances. He lived loudly and unconventionally. His sign of approvals in rehearsals was laughing even about very sad things. He wasn’t writing very much in those, his later years.

‘I believe at the time of his death he was contemplating a play in response to Beckett’s Waiting for Godot,’ I said.

‘That would have been eagerly received, I daresay.’

‘How did you find his directing?’

‘Anything but forgettable, Allan. That’s how he wanted it. He was always opening up more possibilities of how the stage could be used and for what purpose, challenging the tenets of traditional theatre, replacing them with his concepts for a theatre of the scientific age.’

‘Some say he was unbending in imposing his ideas. Was this true, Jochen?’

‘Without a word of a lie, Brecht as a director was anything but doctrinaire. For him practice was paramount. He never discussed theory. Once he had an actual theatre to run, the polemics and the jargon of his youth disappeared. He never used terms like “alienation” – one of his key ones – with us. As did Erich Engel, his collaborator, who carried on his work with us.

People came in to watch rehearsals. Of course, Brecht’s lifelong informing principles, his own unorthodox staging and performance techniques remained the Company’s guiding force.’

‘What were these,’ I asked?

‘Brecht undid the usual associations between the elements of a play. He called his way of disassociation the “alienation effect”. The ‘Verfremdungseffekt”, or more simply the ‘V’ effect”,’ he said, holding up his two fingers.

‘Like Churchill did,’ I said, disassembling the word, identifying the stem word for ‘foreign’. ‘Only for him it meant keeping those ‘ruddy Huns’ at a permanent distance.’

‘It guaranteed them both the supply line to Havana remained open. Anyway, Bertholt trained us to keep a distance from the audience, to encourage its members to retain their critical detachment. His plays are not the classic unfolding of a drama based on the motivations of a particular character, but rather so-called “epic theatre” which removes viewers from the spectacle, theoretically giving them room for reflection.

‘How did this affect the way you acted?’ I asked.

‘We had to prevent the audience becoming too emotionally involved, too swept up in the stories that they didn’t focus on the message. We had to encourage them to see us merely as actors, to discourage them from identifying with the characters we were portraying. This meant we too couldn’t identify with our roles or become the character.’

‘Suffering Stanislavski! How were you expected to produce realistic actors?’

‘We were instructed merely to present them believably, to demonstrate their actions. We would frequently address the audience directly out of character and play multiple roles. Brecht thought it was important that the choices our characters made were explicit, and tried to develop a style of acting wherein it was evident that the characters were choosing one action over another.’

‘What about the sets and lighting?’ I asked.

‘These were designed to prevent the traditional make believe of the theatre from gaining sway. Nothing was hidden. The stage was a stage and nothing more.’

‘That’s like Shakespeare’s. He made the best theatre on an empty stage with nothing, a few hand props, maybe a few costumes. He doesn’t rely on just illustrating things but on creating images in the mind of the people listening though the power of language.’

‘For our part, we used all kinds of devices – placards, songs, and stark white lighting, narrative, montage, self-contained scenes, and rational argument to create a shock of realization in the spectator.’

‘So this was the underlying aim?’

‘It was indeed. We had to encourage the audience to rise above the immediate experience, to keep them aware they were watching a play, to give them a more objective perspective on the action – in short we had to awaken their minds, to force them to make a critical appraisal. You see Brecht was determined to destroy the theatrical trompe l’oeil, and thus, that dull trance-like state he so despised. His plays are not entertainment.’

‘You know, most people go to the theatre to be entertained. They don’t want to see plays about violence, cruel heartedness and warfare. They can get all that at home.’

‘Brecht wasn’t about entertaining. He envisioned a new theatre, more of a debate hall than a place of illusions, where a dynamic between players and spectators was set up, with participants rather than a passive audiences, where underlying themes of social and class conflict could be emphasized.

‘So it’s a very politically conscious politically theatre?’

‘None has been more than the Berliner Ensemble. It’s where Brecht could demonstrate his beliefs in dramatic terms. He wanted to challenge unquestioning obedience and the influence of military routine on people’s ability to judge events independently. He wanted to challenge in particular assumptions about immutability . He argued against the charge that human nature cannot change.’

I suggested some examples of such fallacies. ‘Germans are fundamentally anti-democratic. A German in sheep’s skin is a German, no less.’

‘Once they have tasted blood, people can’t stop killing others, Once a killer, always a killer. Born a whinger, he’ll die a whinger.’

‘Indeed, Bertholt argued things could indeed be different. By putting things in relief, one could see them for what they are – the corollaries of particular historical circumstances, not of universal human nature.’

‘What are the implications of this view for the individual wanting change?’ I asked.

‘As for the individual wanting such change, himself included, Brecht likened him or her to a swimmer – only as fast as the current and one’s own strength and stomach allow one to. He or she has to reckon with the current of society and when one wants to swim against the current, it requires more effort than to swim with it.

‘What about Erich Engel?’

‘Erich Engel, in spite of being a self-proclaimed “Marxist to the core,” took the low key path of minimum resistance, weaving his way through the traffic. avoiding obstructions, swimming along in a winding course, moving from side to side.’

‘He must have done some training in India’, I said.

‘He has been fittingly described as a “wanderer between political systems.” He kept up his friendship with Bertolt Brecht and, living in West Berlin, he managed to continuously build his career as a director without his work ever being banned, whether working under the Nazis, in the G. D. R., or for West German productions’.

‘How did he manage to keep working under the Nazis?’ I asked.

‘Not unexpectedly, he had to be very heedful of circumstances. Like anyone in public life seen to be mildly critical, he walked a tightrope between exile and the gallows. In 1935 he produced the film … ‘Nur ein Komödiant’ in Vienna. Set in the 18th century, this film was opposed to militarism and authoritarianism. You can tell this in the scene when a military officer refuses an order to fire indiscriminately on a crowd of rebellious peasants.

‘How in blazes did he get it passed at that time?’

‘Probably because of the film’s period setting, a royal court of the 18th century.

It seems to have veiled its political stance. It was passed by both the Austrian and the German censors. In order to avoid being commissioned to make propaganda films for the Reich he concentrated on witty, ironic comedies.’

‘What kind of swimmer was Brecht? I asked.

‘As one of the “Generation of 1914” – what you call the “Lost Generation” – he was quite experienced, swimming against some strong currents. He was impacted by the challenging circumstances of early 1919.

That was just after the end of World War I.’ I said.

‘Yes, Soldiers coming back from the front joined up with workers inspired by the revolution in Russia to demand better conditions and security.’

This Spartacist uprising by the German Communist Party was put down in Berlin.

He was always at odds with the prevailing official affirmative notion of culture,’ Jochen said, ‘and continuously sought to challenge, undermine and transform it. He understood art to be more than simply a superstructural affirmation of reality. It was something to forge as a means of transforming society. Brecht defined its role as active and critical appropriation of reality, with the artist confronting, exposing and acting upon real societal contradictions with a view to bringing about social change. Needless to say, this overtly ran counter to the fascist agenda whose agents chopped off his productions.’

‘He had his fair share of enemies in the U. S. too, Jochen,’ I said. ‘I saw newsreel footage of his appearance before The House of Un-American Activities Committee.’

‘Yes,’ replied Jochen, ‘calling him to account for his alleged Communist activities. Like Paul Robeson he refused to bow to it in the intensely intimidating atmosphere. Who could forget the masterful performance Bertholt put on before it, wearing overalls, cracking jokes, and straining his conversation through an acrid cigar. It put some on the Committee on the sick list.’

‘Uh huh, and he managed to outwit his investigators,’ I added, ‘not really answering them, making constant references to the translators who transformed his German statements into English, ones he could not comprehend, convincing the Committee with half-truths and skilful innuendo that he was no threat.’

‘Mindful of the past, he was not going to take any chances,’ said Jochen. ‘He decided to escape this baneful state of heightened irrationality. He didn’t even wait to see the opening of ‘Galileo’ in New York.’

‘How did he go down with the local arbiters of taste?’

‘He often found that his political theories – or even his appearance – did not mesh with those of our own cultural dictators. On one occasion he was refused entry by security guards to a function in his honour. Needless to say, he walked a fine line, couching his suspicions about the regime elliptically, obliquely, in cryptic phrases, and with innuendos that make exegesis a dubious affair.’

I visited Jochen’s home and met his mum and dad. Sitting in his loungeroom we talked about records.

‘What about you, Jochen. How do you see your own swimming track record?’

‘Like anywhere no one annoys you here if you go with the flow.’

‘As do dead fish,’ I pointed out.

‘So long as you conform with what the socialist regime allows on sufferance. Dissidence, in contrast, can result in all kinds of penalties. These begin with the mild, involving the sidelining and withdrawal of patronage for high profile icons like Ernst Busch who fell out with the party. He was untouchable, protected by his impeccable socialist credentials, recorded in posterity for all to hear. Listen,’ he said as he put an album on the turntable, ‘What you’re about to listen to is the unique sound of history in the making. ‘This is “Six Songs For Democracy” recorded by Barrikaden-Tauber.’

‘Who’s ‘Barrikaden Tauber’? I queried. ‘I know Richard Tauber, one of my Mum’s favourites. Are they related?

‘Not really, laughed Jochen, but they were both singers who needed no introduction. Ernst Busch was nicknamed after the Viennese tenor, but not until these wartime songs of his were recorded in 1937, ’38 in Barcelona. He had answered the call to join the International Brigades fighting against fascism in Spain.

You can hear a chorus of soldiers in the men’s barracks. Listen carefully and you’ll catch the noises of wartime activity in the background. The records were cut and broadcast by Radio Barcelona and Radio Madrid.’

Picking up later from where we had been – the topic of penalties in the Democratic Republic, Jochen continued: ‘For lesser dissident mortals, they face being silenced, treated harshly physically, restricted in career choices and socially marginalized. These flagrant violations of human rights are forbidden constitutionally. Because of this concrete experience the question of power is never far beyond the shallow veneer. We are always confronted with it openly and nakedly. In advanced capitalist society the movement of capital determines all questions of power, but it’s much more invisible.’

‘How do they go about flouting the law in such ways?’

‘Those who get away with these transgressions can only do so by hitting below the belt.’

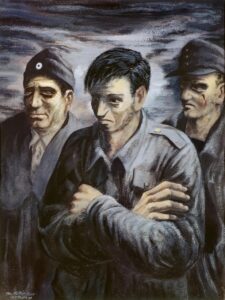

Jochen knew a thing or two about intrigue, and not just from the theatre. A soixante-huitardor “sixty-eighter,” he had found himself in troubled waters that year, his career suddenly and violently interrupted. A physicist by training, he was one of 300, 000 people imprisoned for their political persuasions during the forty year period of the German Democratic Republic. He was a ‘political’, one officially disapproved of or strafed for being involved with an opposition group or attempting to defect to the capitalist states.

He recounted his Orwellian trip to me: ‘I was arrested for giving out leaflets.

‘What was your message, Jochen?’

‘I was protesting against the brutal Soviet crushing of the Prague Spring reform movement. All I was doing to exercise my right as set out in our constitution: ’Every citizen has the right to express his opinion openly and freely.’

‘The Ministry of State Security obviously disagreed.’

‘They reacted strongly to the movement. It was trying to breathe new life into the torpid system. It was calling for ‘socialism with a human face.’

‘What form did your demo take?’ I asked.

‘We used all kinds of devices – placards, songs, and arguing rationally to shock spectators as to the consequences.’

‘What did this mean for you? As well as the stark white lighting what did you experience?’

‘It was clear that the Wall stood on more solid foundations than we had imagined’, he said. ‘Hardliners both in Prague and Moscow feared it might take the country out of the Warsaw Pact. I was incarcerated not ‘self-contained’, mind you, at the Hohenschonhausen prison in East Berlin. They held me for a long period in solitary confinement. We were checked all the time through a spyhole. I spent seven months without knowing my sentence, without newspapers, without visitors, without anyone to talk to, without seeing the sky.’

‘They inflicted sensory deprivation on you,’ I said.

‘It was a world of silence. The only thing I got to hear was the banging of the cell door and the knocking of it’s bolts.’

‘What else did they do to you? I asked.

‘ We had to sleep facing upwards with our hands by our sides. They kept the lights on night and day.’

We had to sit on our hands for hours while being interrogated.’

‘They must have been afraid you might overpower them and bust out the prisoners in all the blocks.’

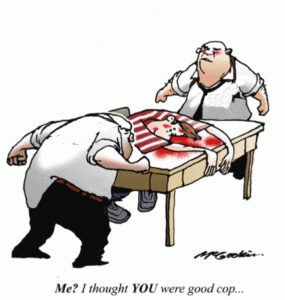

‘This was no blockbuster. They just wanted to keep us in a state of passivity. Like other prisoners, I was subjected to a variety of psychological punishments by the Stasi, alternating between hostility and friendliness. One minute they’d be coming down hard on you.’

‘Look, we can do this the easy way or the hard way,’ I said, suggesting what they might have proposed . ‘We could initiate you in the Holy Sacrament of Confession.’

‘The next minute they’d be all matey, trying to soften you up. You’d feel like saying anything they’d want you to out of gratitude.’

‘The old ‘good cop, bad cop’ schtick, in reverse’ I said.

‘Their perverted version of the ‘alienation effect’.

‘With alternating current,’ I suggested. ‘Did you encourage them to look upon your motivations not as those of a particular character, but rather of one involved like them in an epic moment. Did you encourage them to retain their sense of critical detachment, to have lots of room for reflection? Did you try to keep some distance from them?’

‘Not as far as I would have liked – namely a thousand kilometres.’

‘So it was a prison and nothing more,’ I said. ‘No shock of realization on the part of the screws at what they were part of’.

‘Hardly’, said Jochen. ‘They were actors in this same drama but under a different directorship. How do you awaken the minds of the comatose? We needed a transparent process, the people as the audience watching how the state mistreated its citizens.’

‘Lay out more details for me,’ I asked.

‘They aimed to dehumanize us by not calling us by our names. I learned to respond to “number one”.’

Then all of a sudden by way of contrast we would be treated humanely during their interrogation sessions. This created immediate sympathy for the interrogators. “By the end of isolation, you were willing to spill your guts out about anything”, said Jochen. ‘I became so desperate during this period I faked a suicide attempt. I was moved straight away to a two person cell. Eventually came our formal sentencing. The sentences were overstated to lower our morale. This would allow the offer of shortened sentences in exchange for ‘rehabilitation’. After being sentenced to 30 months imprisonment, I was placed in a cell containing 33 prisoners in the Commando X section of the prison. These prisoners were a hodge podge of political and common prisoners. The head prisoner in the cell was a 25 year old murderer. I saw a 20 year old thug break down a 68 year old professor. There was an atmosphere of fear”.

‘So the other prisoners were very much used to get back at you?’

‘The screws created an environment of mistrust by rewarding stool pigeons. We ourselves became responsible for our behaviour through a system of collective punishment. That’s when we felt the heat. ‘Politicals’ were dished out additional punishment by being put in the ‘the hot room’, a special cell kept at extremely high temperatures. At roll call you could usually tell who had spent the night there by the paleness of their faces’.

‘What advice would you give to anyone to make all these humiliations bearable?’

‘I would advise them never to match rudeness with rudeness, never to be provoked, never to score, never to be witty or superior or intellectual, never to be deflected by fury, or despair, or the surge of sudden hope that an occasional question might arouse. To match dullness with dullness and routine with routine.’

‘What happened when you were eventually let out? Did it all stop there?’

‘After I was released I was not allowed to pursue my PhD in physics. My career should have been on an upward trajectory. Instead, the Stasi discouraged employers from giving me work. On several occasions I had agreements with professors to work in physics labs. Only then I received a letter just before I was about to start informing me that another candidate had been selected’.

‘What does the State consider you are lacking in?’

‘I need only 1.5 grams for employment as a scientist or professor. This is the weight of the Communist Party sticker.’

It was apposite that Jochen explain to me the contradiction of his country – it’s support for countries like Vietnam and Cuba fending off foreign assault, at the same time as its abuses of the civil rights of its own citizens – as we walked along Karl Liebknecht Street.

‘This block was named after the martyred Spartacist leader of the 1918 attempt at a Bolshevik style revolution . He would be turning in his grave if he knew how his ideals were degraded so. Starting with the German fleet’s rising in Kiel – in which, incidentally, Busch took part – the rebellion at least ended the Kaiser’s rule and to the series of republics.’

Dies ist unser land.

‘Let’s face it, our little republic has been up against it from its very inception’, I remember ‘Number One’ saying as we tucked into some grilled chicken in a restaurant.’ It was based on fear—‘

‘Tell me about it,’ I said.

‘Are you sitting comfortably?’ Jochen asked. ‘Do you have a fortnight spare?’

‘Jochen, this expression means ‘I understand what you mean’. While our recent history is not as traumatic as yours, it too has been blighted by this irrational fear.’

‘It was based on scarcity. You couldn’t get these goldbroilers when I was little. They were as rare as their mothers’ teeth.’

‘A knife and fork don’t get all the precious flesh easily. This brings up a point of etiquette. Can fried chicken be eaten with the fingers?

‘No. Fried chicken should be eaten by itself. The fingers can be eaten separately.’

‘There wouldn’t have been many chickens eaten during the war, I guess.’

‘That’s true but for some there was no shortage of fingers.’

‘Shortages are not just a feature of the planned economy. Let’s not forget it was like that not that long ago in the U. K. Rationing for food there only ended only in 1953.

Even when people did get their hands on a prized morsel, it was hardly a delicacy worth eating. ‘What was the worst here?’ I asked?

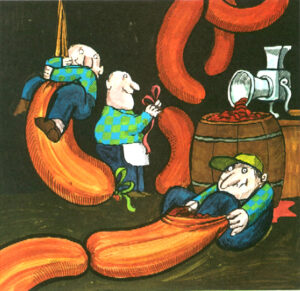

‘For many the ‘wurst’ was ten years ago. We had the great sausage shortage.’ Plenty of apples and red cabbage for sweet and sour cabbage and sauerkraut. All very well and good but you need some sausage to go with them.’

‘The British people didn’t know what they got in theirs. Butchers added leftovers to make ends meat. ‘Sweet mystery of life’ people called them. They contained more bread than meat. ‘Why queue for them?’ they asked. ‘You can get bread without queueing, the other side of the street. They didn’t know whether to put mustard or marmalade on them. How did people cope with this here?’

‘Most were patient and adjusted their diet. They made light of it.

A man walked into a butchers shop. He asked the assistant, ‘You don’t have any lamb?’

The assistant said, ‘No, here we don’t have any beef. The shop that doesn’t have any lamb is in the next street.’

Another man asked in the shop for a large sausage.

‘Sure, it won’t be long,’ replied the butcher’s assistant’

‘Then I certainly hope that it’ll be wide then’.

Others got fed up queuing in lines for them. After a particularly long and cold wait one wintery day, it proved too much for one hard core sausage addict waiting for his fix. I’ll tell you the story of his ordeal. He needs to make contact with Joe. This is the ballad of Porno Joe who pops up wherever you need a hit but there are shortages. He’s your average Joe, an antikonformist. He’s as racy as a Thüringer Rostbratwurst. If you want any sausages all you need is to talk to him. He’ll find some for you. He He knows some small business operators .They’ll busily grind any meat they get their hands on and stuff it into casings.

He’ll find a way to fix you up. ’

‘Good day, my fellow citizen, ‘excuse me but are you a colleague of The Sword and Shield?’ said the addict to a man beside him in the queue, referring to the Stasi.

‘No I’m not. Otherwise, why would I be here queuing? They know who is to get something and who has to wait.’

‘Are you a former Stasi comrade?’

‘Hasn’t that become clear?’

‘Among your relatives and close circle of friends, are there any Stasi comrades?’

‘None that I’m aware of. Otherwise, they wouldn’t be doing their job.’

‘In that case, please move your foot. You’re stepping on my toes.’

Once freed of this burden, he waited and waited and waited, day dreaming of some beautiful bangers. He finally lost his cool when the line came to a complete stop,

crying out, ‘I’m fed up! I’m not going to wait in line any longer. I’m going to the General Secretary’s office to throw a snowball at him.’ Then he turned around and left. But a short time later he was back.

‘You’ve thrown it already?’ asked another.

‘Gottverdammt!’ he replied. ‘The line over there is longer than the line here!’

‘I don’t see many lines for fruits and vegetables’, I said to Jochen. ‘In fact, I don’t see many kinds on offer.’

‘They’re almost impossible to buy in decent condition and only come in dribs and drabs.’

‘Why so?’ I asked.

‘Variety and freshness are certainly not among the virtues of the DDR food regime. Our over centralised transport and storage systems can’t effectively make short work of perishable goods. It’s not the workers’ fault.’

‘There’s an old saying, Jochen: ‘a fish rots from the head down’. If the servant is disorderly, it is because the master is so.’

‘It’s labour – the servants of the state – that we are short of. Our political masters don’t know how to attract sufficient workers from elsewhere. However, we get by with our plain tired fare. There’s no absolute shortage but getting a good assured supply of pleasant food is a constant source of worry. You’ve got to go to a lot of trouble to find those occasional opportunities and windfalls. Waiting on lines, struggling with the personnel of the state food stores, getting access to western currency, going through complicated barter improvisations and rescuing marginal vegetables. You get what you can when you can. People tend to hoard and stockpile.

Nevertheless our per capita food consumption and caloric intake is good enough. We live on the pig’s back. We like our meat and we get it. The main problem is a lack of variety.’

‘What kinds don’t you get?’

‘It’s easier to say anecdotally what we do get.

I once went into a butcher’s shop along with Porno Joe to get some pork-as usual. The old guy ahead of us asked ‘Half a kilo of beef, please.’

‘We don’t have any beef today,’ came the answer.

‘Never mind, I’ll take a leg of lamb instead’.

‘Our lamb is all sold out’.

What about some venison?

‘You must be joking.’

So this customer just shrugged his shoulders and walked out. The butcher turned to his colleague and remarked ‘Hasn’t that guy got a fantastic memory!’

Then Porno Joe says, ‘I’ve got a party coming up and I want to barbecue some chickens. Can you get me some?’

The butcher said, ‘I can get you two.’

Joe said, ‘Alas, I’ve got twenty friends coming, and Jesus isn’t one of them.’

‘It must get boring eating pork all the time, Jochen. Can’t you get around this?’

‘Sometimes a butcher will try to pass off pork as beef.’

‘That sounds like a recipe for trouble.’

‘ For sure. There are some loins you just can’t cross.’

‘Well, there’s certainly no shortage of humour about shortages, are there?’

‘Picture this now. Four guys were waiting on the platform for their train: a standoffish Party functionary, a North Korean student, a bumptious high ranking Stasi party official, and of course, Porno Joe. A reporter from ‘Neues Deutschland’ comes up to them and says, ‘Excuse me, I’d like to know your opinions about the shortage of veal for our newspaper?’

The North Korean replies, excuse me, what’s an opinion?’

‘And you, Comrade?’

The party functionary, well connected, who knows everyone in meat, says, ‘Excuse me, what’s a shortage?’

‘It’s what led to the decision made to import so much from the west.’

‘It’s important to realize that the greatest shortcoming of capitalism is overproduction.’

‘And you, Comrade worker, excuse me, what do you think about the veal shortage?’

Porno Joe says, ‘Excuse me, what’s veal?’ ‘

‘Are you a regular reader of our newspaper, Comrade?’

‘Of course. Otherwise how would I know about the happy life we live today’.

‘What is the main advantage of our planned economy?’

‘It’s ability to successfully overcome difficulties that don’t exist in the other system. In our system planning is everything.’

‘Do you have an opinion about it?’

‘I do have one, but I don’t agree with it.’

The Stasi official, in his turn says, ‘Excuse me? What’s excuse me?’

‘Secret intelligence agents are not known for their manners are they.’

‘Listen to this. A German worker gets an engineering job in Siberia. Aware of how all mail will be read by Stasi censors, he tells his friends: “Let’s establish a code: if a letter you will get from me is written in ordinary blue ink, it is true; if it is written in red ink, it is false.” After a month, his friends get the first letter, written in blue ink: “Everything is wonderful here: stores are full, food is abundant, apartments are large and properly heated, movie theatres show films from the West, there are many beautiful girls ready for an affair — the only thing unavailable is red ink.”

‘‘Yet you get by in spite of such hold ups and attitudes?’

‘And spiced up by our humour. We don’t have all the ingredients that you have in the West. With nothing to speak of, one manages to be very creative. We get by. There’s a whole category of things we consider “nicht schön, aber brauchbar – not beautiful, but servicable’.

‘You should be getting beautiful food, ‘ I said. You need to be doing something different here. Not marketing mass produced industrial food as gourmet ingredients.’

‘We can do better than Tempo-Linsen lentils. They’ve been chemically-treated for quick cooking. Then coming in a cooking bag we have Instant KUKO-Reis.

‘That’s cuckoo.’

‘And then for dessert, we’ve got Rote Grütze. It’s not from berries, like in the West, but from powder and tastes more like chemistry.’

‘You shouldn’t be trying to catch up with the West, but leading it in something better, more natural. Not a mediocre knock-off of what we’ve got. We’re lagging behind ourselves in what we should be providing for our diet. What vegetables we have we boil away the goodness. We’re far too heavy on grease. We’ve got our own ersatz food. We’ve abandoned fresh orange juice as a drink in favour of cordial. We’ve substituted plastic cocktail frankfurts for real sausages, canned pineapple for fresh fruit, processed cheese for the wonderful range of fresh cheeses.

If they can be stuck quickly on a toothpick, all the better.’

‘We’ve had a shortage of toothpicks and pins. People have used them as barbeque skewers.’

‘We’ve forsaken fresh coffee for instant coffee.’

‘Our coffee, ‘Rondo’, ’said Jochen, is like a neutron bomb? You die, but the cup stays intact.’

‘We ourselves are going through a big reaction against mass-production of food.’

‘La nouvelle cuisine’, said Jochen. ‘More emphasis on quality and minimalism.’

‘A revival of local foodways, regional identity and artisanal techniques,’ I added. ‘producing delicacies like Stilton cheese to set off the olfactories .’

‘Hopefully it will take off here and get underway’, said Jochen. ‘Our leaders hit us over the head with the directive ‘Produce more!’ but don’t know much about quality.’

‘I’ve noticed that with the grey toilet paper. It’s as hard as that in English schools. And I’ve also noticed that government offices are supplied with softer more two ply product.’

‘That’s because officials have to send a copy of everything they do to Moscow.’

‘They’re totally into quantity, aren’t they.’

‘Officials like to cite how many pounds of meat, how many kilos of sugar and how many eggs we consume. And how far our little republic has come in its twenty five years existence .’

‘It wasn’t an easy start, was it, ’I said.

‘All things considered it had little going for it. We need to look at the historical context. It’s rationale for being was as a buffer against another attack by the West on the Soviet Union. “Stalin’s unwanted child” began life at a great disadvantage compared with the Federal Republic.

‘I’m sure it preferred to be an orphan.’

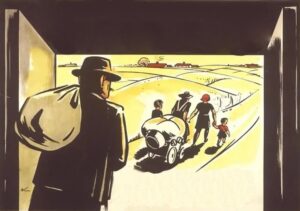

‘It wasn’t given a choice. Comprising only a third of German territory with a population of 17 million, as against 63 million in the west, it was considerably poorer. It had little heavy industry and few mineral resources. It also had an influx of literally millions of German refugees from lands further East.

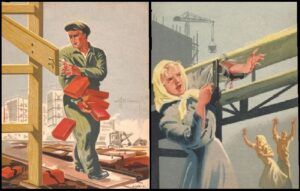

Homes and workplaces had to be built to accommodate them. This was part of the process of rebuilding after the destruction endured during the War.

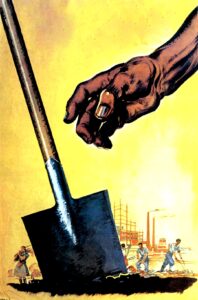

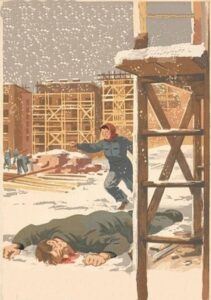

Because of the push for rapid construction, accidents and slip-ups were commonplace with workers suffering from corners being cut. Insufficient care and neglectful positioning of materials often led to skin tears.

Too many things–and people–fell down in the rush for work to be finished.

These accidents could be fatal.’

‘They were dark, difficult times indeed. Moreover you had to pay compensation for the damage the Nazi military had caused to other countries.’

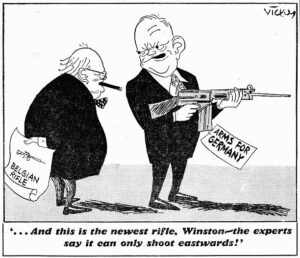

‘We had to pay disproportionate massive reparations to the Soviet Union devastated by the Third Reich, representing all Germany. Compare this with the FRG.’s economy, underwritten by The United States, former armourer to the Allies, bursting at the seams with war industry proceeds.’

‘The U. S. downplays this. Having remained on the sidelines through a good part of the war, they largely avoided the damages that ruined their rivals.’

‘Our main trading and technological development confederates were to be the relatively poorer and less developed nations of Eastern Europe and the USSR, whereas the opposing FRG has had as its economic allies the richest and most technologically advanced countries in the world. While the U. S. injected capital and provide technology transfer into the F. R. G., there was a transfer out of our Soviet occupied zone. The U.S. displayed it’s wealth to impress on our people that life in the West was easy and full of pleasure.

The F. R. G. benefitted as part of an economic bloc profiting from it’s investments of resources in those poorer countries integrated with the international capitalist system. It’s never been a straight fight. This imbalance in possibilities for economic development continues to this day. That’s about the size of it.’

‘What about the political flow-on of this imbalance, ’I asked.

‘Anyone who expected a superior democracy to grow out of ashes and rubble by a bitter defeated disillusioned starving people manipulated by an authoritarian Russian overlord and forced into a crazy arms race is naively mistaken.

I resent the glorifying hypocrisy of our dear leaders who hymn the virtues of our ‘workers paradise’. Because our eyes give the lie to this claim, it’s counter-productive.’

‘It’s not as if socialism can flower in a siege mentality or be imposed by tanks. I would be the last to whitewash, gloss over or apologise for our human rights abuses. They are inexcusable. At the same time, this is not to deny our genuine achievements, hidden from the casual observer. We have forged a distinct collective identity. From cradle to grave, everyone has access to free fine health and educational facilities. People have jobs, crappy or not and a roof over their heads.’

‘Aren’t these comparable in the F. R. G.?’ I put to Jochen.

‘Indirectly we’ve helped boost the wages and social welfare benefits of West German workers. Competing against us as its ideological rival, the West German ruling class has been pressured to make concessions. You might say that one of the most lasting effects of Communism has been to save its antagonist both in war and peace – that is to say, by providing it with the incentive, fear, to reform itself.’

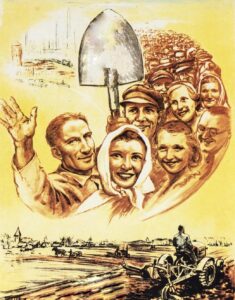

‘In any case, in spite of the balls and chains we’ve carried, we’ve managed to build a standard of living higher than that of the USSR, of millions of inhabitants of the American ghettoes, of countless poor white Americans, and of the population of most Third World countries. We’ve got flatlining crime, and women –who, by the bye, make up half the workforce, are safe at night on the street. Work is so much more than a source of income; life revolves around the workplace. Companies often have their own singing or sports clubs, and their own childcare and health services. Workers and farmers can spend holidays at subsidised prices. In spite of the state as much as because of it, people act cohesively, look out for each other, depend on each other.

‘Living under a paranoid, mind manacled bureaucratic dictatorship and standing in long food lines has created a feeling of solidarity’, I suggested.

‘There’s always been the will by a good many to build a new society, to make a clear cut with the past’, Jochen continued. ‘Despite problems, there’s always been some air of optimism about the future and the belief that it was possible to create a new and better society on the basis of socialism. The first GDR government contained cadre returned from exile with a track record of active opposition to the Nazi regime.

They genuinely cared about the welfare of the people. Many had spent years in concentration camps and prison.’

‘And we are now aware that some former Nazis have been reinstated into West Germany’s government.’

‘Some of the defeated Nazis were used as allies of convenience by both sides at the end of the war. It’s believed Klaus Barbie, ‘The Butcher of Lyon’, was recruited by the West German foreign intelligence agency Bundesnachrichtendienst –the BND. He came recommended by the CIA.’

‘How could this have happened?

‘The goodwill between the Allied victors had dried up as quick as a flash. This gave the old unapologetic Nazis the opening they’d been waiting for. The C. I. A. made contact with them in the bombed out backstreets of our cities, recruiting them into their clandestine war against the Soviets.

There were always those elements in the American military who saw the Soviets as the biggest threat to civilization.’

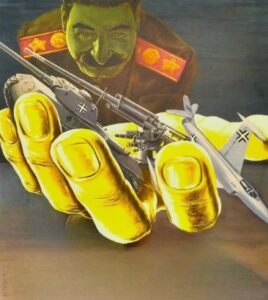

‘Hence the network of stay behind “secret armies” the CIA set up. Some former officers of the Wehrmacht were selected to become officers in NATO.

Working with various Western European intelligence agencies, the “secret armies” were the most powerful armies you’ve never heard of.

‘Their members may have discarded their uniforms but they maintained the old ideas.

.

They have engaged in subversive and criminal activities in several countries and been responsible for a series of terrorist atrocities we have read about. They pursue a “strategy of tension” with the aim of preventing a rise of the Left in Western Europe . Let’s look at their exploits. In Turkey in 1960, the stay behind army, working with the army, staged a coup d’état and killed Prime Minister Adnan Menderes; in Algeria in 1961, the French stay-behind army staged a coup with the CIA against the French government of Algiers, which ultimately failed; in 1967, the Greek stay-behind army staged a coup and imposed a military dictatorship; just recently in Turkey, after a military coup, the stay-behind army engaged in “domestic terror” and killed hundreds.’

‘In keeping with this policy the Americans use Nazis like Barbie in the belief that they are the most valuable experts on fighting the Soviets and can get the job done the most efficiently.’

‘Some kind of experts,’ I said, ‘Them having been defeated by the Russians. Another case where the means are used to justify the ends. A thoroughly totalitarian concept from some very nasty people. They’re selling it to dictatorships in Latin America which reminds me of a black joke told by an Argentine in exile: ‘Hitler, who escaped his ‘farterland’ on the ‘ratline’ is alive in his Andean aerie, pursuing the quiet life. A group of neo-Nazis on The Company payroll come the same way to talk him out of retirement They begged him to lead them in their quest for world domination. He refused point blank insisting it didn’t work last time. However after their persistent imploring, their hero, with many a weary sigh, finally agreed to give it one more try – but on one condition: ‘OK, ‘ he said.’ but this time – no more Mr. Nice Guy!’

‘The more agents like this have inflated the threat from our side of the Curtain, the more they’ve justified their work. And the more our intelligence service has been able to justify theirs. Because our destiny became bound up with that of the Soviet Union, this also meant party hacks and antediluvian apparatchiks, controlling from the top, dug in behind their mental walls – ‘Mauer in den Köpfen’. Growing up, I embraced this connection as only a child would – I bawled my head off when Stalin died. We had a firm conviction that were making progress towards a better future and higher purposes, towards the New Man – that’s what shaped us. I rest my case.’

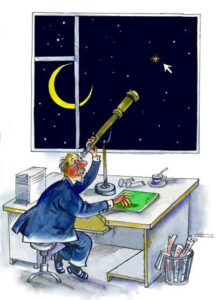

‘Was it the Soviet space flights such as that of Gargarin that inspired you to study physics?’, I asked Jochen.

’Not so much. More it was in the spirit of Galileo that I chose this path. Galileo’s argument being that “the only purpose of science is to relieve the hardship of life”, I set about embracing this reality , taking refuge in science. I put together my very own telescope. Have you ever had one?’

‘I’ve never owned a telescope, but by Jupiter it’s something I’m thinking of looking into. They can help you discover celestial objects invisible to the naked eye.’

‘I used mine like Galileo to observe such marvels as the moons of Jupiter, the mountains on our moon and sun spots. Familiar sights to us now, but seen by no other person than Galileo at his time. I wanted to understand the laws of the universe. How its order contends with hellfire, chaos and planetary pinball.’

‘As for exploring it we haven’t taken off as we should have back here on earth’.

‘In our case we’ve failed to create a genuine socialist country in every sense of the word. Where people run things openly and democratically, not just on paper with empty phrases, without fear of unjust treatment. This is the only bedrock on which we can defend our gains, compete with and edge out the F. R. G. We have to create a model worth copying, learning from or adapting for use elsewhere. One where people will clamour to get past the cordon sanitaire – in the opposite direction.’

I learned a lot from my year in the divided city, enjoying the thrill of living in such a strategic geopolitical location. Then it was high time for me to up and make tracks again for the Disunited Kingdom. Birds in the winter sky were heading for the sun. My aim was to sock away some nicker to get homeward bound. I fretted for my family and was anxious to catch up with my parents. Torn between staying and returning emptyhanded, I became more highly strung than usual.

As a hireling, I was happy enough making my way along a non-career path while young and venturesome, but I remained fully intent on advancing professionally. I wanted to do something with my life, to get somewhere, to find the best avenue for my talents and lifestyle. Back in Blighty I would widen my teaching experience and advance just around the corner to new fronts, politically, my solidifying beliefs becoming evident, moving beyond seat of the pants decision making to planning, and at long last – wonder of wonders – romantically. No more living out of a bag. No more rovin’ an’ wanderin’.