Worlds Apart.

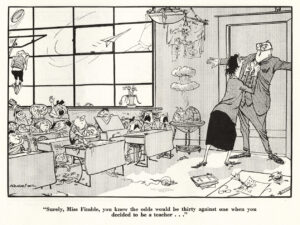

I put in the next several years except one jobbing as a supply teacher with the Inner London Education Authority, the largest public education administration in the world. This gave me a very wide experience as I taught children from infants to lower secondary. The schools were mostly secularly administered while some had Anglican or Catholic affiliations. Not having a a contract meant I could fit in travel and study for my post graduate degree.

As a circuit rider I worked in schools all over West and North West London at short notice- sometimes for a day, sometimes for up to a year. I moved on when I was all out of party tricks. As well I spent many hours in the old schoolyards, not just as a teacher but as a relieving school caretaker and an after school and holiday time play care assistant. I observed how children respond differently than adults to the same stimuli.

What kind of school I worked in depended on what was available.

My first foray into a secondary school proved rather disconcerting. The boys I was assigned to weren’t particularly up to no good. They just wouldn’t give me the time of day.

The headmaster introduced me, saying,’ Boys, this is Mr. Davis. He’ll be taking you for the rest of the term.’

‘Our condolences,’ said one boy.

Another commented to his mates, Look what the cat dr—,

‘I heard that. That’s enough !’said the headmaster looking their way, ‘would you like to elaborate—perhaps in detention? If I hear anyone talking like that, they’ll be straight to a two hours stay after school. Clear?’

After he left I stood at the front of the room patiently waiting for the fidgeting and showing off to dissipate:

‘OK, class, I don’t know if you’ve noticed but I’ve been standing here five minutes waiting for your attention. Now could you put a lid on it and direct your eyes to the front. How about it?’ I need an auditory response. Don’t answer all at once,’ I told them.

‘Say what?’

‘What,’ I replied, trying to break the ice.

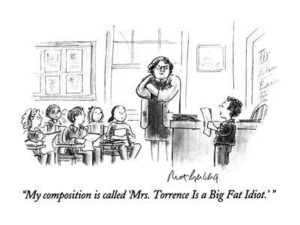

‘Who’s this clown?’ one of them said, pushing my buttons, not caring if I heard, ‘ Where do they find them ? When are we gonna get a real teacher?’

‘When you get to make the fast progress I aim for, you’ll hopefully say I’m unreal.

‘What would you know?’

‘If you’d like to know, I’m more than sufficiently trained to get you through your exams. You over there in the turtle neck sweater,’ I said, pointing to one boy who had been pulling rude faces, ‘name me two pronouns.’

‘Who, me?’’

‘Correct. You know more than you like to let on. And did you know using double negatives implies a positive.’

‘We’ve already learned that. We don’t disagree with that.’

‘Well done. But never does a double positive imply a negative.’

He said, ‘Yeah, right.’

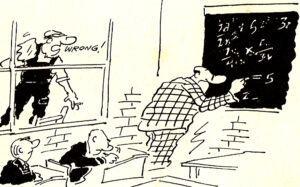

As soon as they knew I was a supply teacher, they tried to take advantage of me. Like offering me forged absentee notes. They started humming and making noises when I turned my back to write on the board.

I could talk to these tearaways individually but as a group they were past caring.

‘Come on now guys,’ I said, urging them to interact with me one mondayitis morning, ‘Tough weekend? What’s the deal here? Football? Are you coming to school to learn or just to have fun?’

‘Mr. Davis, You’ve got it at last. We’re only here for the beer.’

’They strained to get out of the classroom like greyhounds in the slip. They thought they were too cool for school. These Crombie boys, like other wayward youths throughout the country wore Crombie coats, Harrington jackets, with silk hankies and tie pins in their top pockets. The principal told me they were all alike in so many disrespects. I was advised, seeing I was the next victim, neither to get too close nor go too hard on them but to just hold the ring :

‘‘ Welcome to the jungle. ’said one department head, ‘I’m sure I’m not the first to tell you this, but don’t feed or tease the animals. Don’t even think of it. They bite. Never raise your hand to them. It leaves your groin unprotected. Let your ribs take the brunt if you get a beating. Use your arms to protect your vital organs. Lower your chin. Protect your carotid artery. If that doesn’t work wait until Detective Smithers can come and sort them out.’

‘I’ll make sure I keep them on side.’

‘Keep yourself to yourself. They’re not among the top sets. Undoubtedly you’ve seen people like them, but you would have had to pay admission.

Some should carry a ‘Warning’ label. We don’t want a bear garden here.

Our task is to tame the beast.’

‘They’re going through the pangs of puberty,’ I suggested, ‘that awkward age’.

‘Too true. Too old to say something cute and too young to say something sensible.’

‘There seems a high turnover of children. Yet their numbers are maintained. They come and go.’

‘Actually they go and come. Every time these mannerless young pups bunk it they are dragged back. Like stray dogs, they’re here one day, gone the next. If they keep this up we’ve half a mind to issue them life membership.’

‘Why do you think they behave like this? Is it innate or environmentally determined?

‘They’re born bad, I reckon, though liberals see these bell-heads as victims of social oppression.’

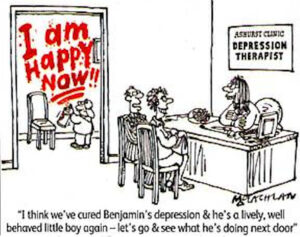

‘Nobody’s born bad,’I replied. ‘ Like anything, it just takes a lot of practice. Anti-social behaviour is something that people learn. If you can learn to treat others with disrespect you can learn to be kind. Teachers have to understand the conditions in which children learn.’

‘Just don’t fall for this modern nonsense about emotional problems. Broken homes and so on. Delinquents play up to this. They come up with such excuses as, ‘My family don’t understand me. It’s not their fault though. They’re poor. My old man’s a drunk. My sister makes love for a pound note. My mother, well I don’t know if she’s really my mother. That’s why I’m disturbed. It’s on account of I’m deprived. But don’t let me put you off. Gird you loins and stick it to them. We need you to stay here at least until the school holidays. Changing teachers unsettles them.’

‘Gotcha.’

I asked one teacher, ‘To what do you attribute this violent delinquency among the boys.’

I believe they pick it up from films. I took one boy to see the newly released ‘Clockwork Orange’ and he cried all throughout it.’

‘You’re not serious.’

‘No fooling, But maybe that’s because he didn’t know who I was.’

I accompanied these backstreet kids unleashed on an excursion to the tranquillity of the countryside. This was a good opportunity for them to escape the murky greys and browns of their home surroundings.

‘Have a care, children. You had best behave yourselves,’ warned the coach driver as the kids chattered away. You had best behave yourselves. So put a sock in it. On a coach trip we sit quietly in our seats and we don’t do do anything else. Do you read me?”

This, as it proved, was optimistic. A trio of boys started smoking at the back of the coach within minutes of the coach’s engine starting up. As they drove off a show of hands were raised in two fingered gestures to anyone who was passing. The driver had to pull over to rant explosively at the three stooges for disrespecting him by constantly singing about him.

‘O.K. You’ve had your fun. Now pack it in or we’ll go straight back to school.

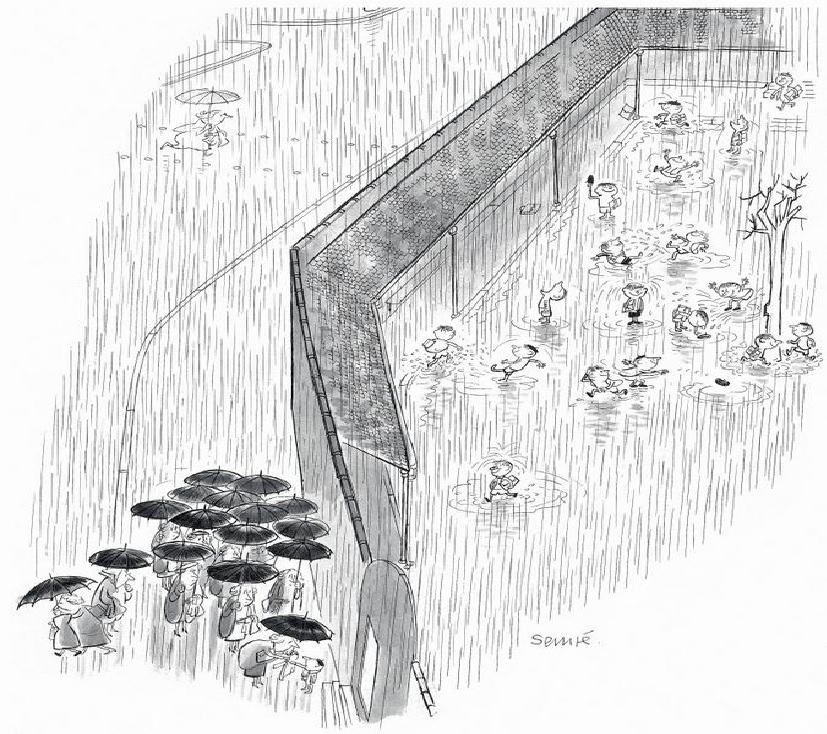

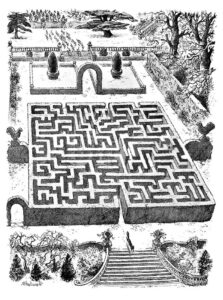

Once they had settled down I proceeded to give them a commentary on our destination. ‘The elegant house we’re going to visit is is one of the finest stately homes in England. It’s set in impressive historic gardens featuring a hedge maze. These mazes used to be all the rage for the wealthy to show off.’

My mother always gets in a rage when I don’t keep my things tidy. She says, ‘How do you expect me to find my way through this maze?’

‘Are we there yet? ’asked one of my boys who I noticed had been been swigging a bottle of soft drink and was now shifting restlessly in his seat.

‘Not yet, Michael but it won’t be long now. I didn’t realise you were such an eager student of architectural history. I sure the wait will be worth it.’

As we got closer I continued my commentary to the boys , ‘Now some of you might feel like a bit of action after inspecting the grandeur and opulence of this mansion. As your reward after our inspection indoors you’ll have a lot of fun outdoors in the maze.’

Are we there yet?’ Michael kept asking constantly, going red in the face.

‘Not yet, Michael. Hold tight. No need to get anxious. Just be patient.’

‘Boys,’ I continued, ‘ the “walls” or dividers between the passages in a maze are made of vertical hedges. The maze has more than one possible route between the outside and the centre. There are as many dead ends and paths as possible to confuse you.’

‘Sir, are we there yet?’ Michael asked again.’

‘It won’t be long, lad. Just hold your horses. Now where was I? Yes, visitors can lose themselves in their attempts to find their way to the centre. It is very easy to get lost in a maze. Of course in getting through some are very clever and can easily outfox others. ‘

As we got close to the manorial estate, Michael cried out, ‘Stop, let me out here. I can’t hold it in any longer.’

‘Hold on, lad,’ said the driver, pulling up. ‘Here’s what you’ve been waiting for.’

When he jumped out of the coach and raced headed towards the maze, it became clear what Michael had been holding. He had been holding his water but from fear of embarrassment hadn’t let on. He had been holding nature’s call.

After we inspected the house, we went back to the maze. The maze-keeper said, Be careful, boys, the maze still confounds visitors. We once lost an entire party of schoolchildren within its hedges. We even lost a number of gardeners. After that we took steps to prevent that from ever happening again.

After we left the estate we pulled in at a roadside motorway service station they were robbing it of their lollies, rendering it’s cash register seriously unwell.

The driver told them scoldingly, ‘I’m banned from stopping here any more. I trusted you lot and this hoo-hah is the way you repay me. You don’t deserve to get out like this. Trust is something you blessed lunks don’t understand. It has to be earned. Is it any wonder people won’t do anything for you. The moment we start to treat you like grown ups, what happens? ‘

I told the boys, ‘ That was uncalled for. You’re lucky to have a driver like ours. Why do you think he’s here? Who do you think he is? An accomplice? By treating him like this you make it harder for the groups who follow us. Future outings may be cancelled. Everyone would be penalised. You know your limits. No more cock-ups. Please do the right thing.’

The boys looked around at each other and one of them made a quick whip-round to bring back some health to the sweet counter’s till. They collected more than enough to make up the shortfall which the driver passed on to the station manager. They parted with a handshake.

‘OK boys, times-a- wastin’,’ I called out. ‘After that holdup we can finally head back to town. Please no more shenanigans.’

In the predominantly white area of the school, I had one lad who was the only black in the class. The chocolate chip in the vanilla ice cream. It was tough for him. It was so hard for him to be absent.

‘Are you working hard or hardly working? I asked one frizzy haired, lazy eyed, likely lad, George Ramsbottom, all knees and elbows, protruding teeth, luxuriant peach fuzz above his upper lip.

‘Before too long you’ll be sporting a full beard, Georgie.’

“We Ramsbottoms are a hairy lot. I was talking to my mum about how quickly it takes us to grow a beard, and she agreed.”

He usually looked spaced out. Some days that boy seemed as if he was on another planet. In fact this serial chiller’s head was always somewhere else.

He was like a solar eclipse. You didn’t see him often but when he appeared it was something special.

‘Where is George today?’ I asked one of my colleagues.

‘He’s fifteen. That’s where he is. He thinks he’s his own boss.’

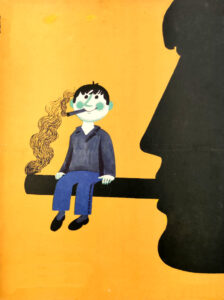

He was brought back to school by his father after he sprung him smoking hashish.

‘I came home and lit upon my son rolling a Camberwell Carrot,’ he told me – from my very best stash too!’

‘George did this behind your back?’

‘Well, let’s just say this. He didn’t do it in front of it.’

‘You should be happy at least he’s not buying it himself and getting mixed up with dealers.’

‘He learned the hard way not to try that. What he thought was hash turned out to be pellets of rabbit shit.’

‘That goes to show, doesn’t it. I guess it was about as useless as smoking mellow yellow,’ I said, referring to the fallacious belief that smoking dried banana peel would get you stoned. ‘Your boy always has his head in the clouds. Did he manage to get any higher?’

‘All he got was pinkeye.’

‘It’s not good for children to smoke,’ I said. ‘He should give it up before it becomes a habit. Parents should set the right example.’

George’s sister also picked up the smoking habit.

Her father confronted her and said ‘A little bird told me you’re smoking cigarettes…’

She replied “All right , I smoke tobacco, what do you smoke that makes you talk to birds?”

‘Was George able to kick the pastime?’

‘He promised his father he’d stop but then he postponed it.’

‘At least father and son have something in common,’ I told the colleague.

‘He gets all his looks from his father. Mostly the look of disappointment.’

‘If you’re thinking of smoking my supply, ’the father told him… ‘don’t’.

I find that confusing,’ replied George. ‘Do you mean don’t smoke your gear or don’t think?’

‘I’ll leave that to you to work out.’

‘Well, what if I don’t want to give over smoking your gear?’

‘Son, I can’t make you stop, but I can sure make you wish you had!’

I got to meet the father on Parent’s Night, ‘Mr. Davis, I’ve heard lots of things about you.’

‘Good things I hope.’

‘Thanks for looking out for my favourite son.’

‘I’m your only son, Dad,’ George pointed out to him.

‘Who’s counting? Mr. Davis. You may have heard some weird stuff about me and my excitable boy, but I wish to tell you they’re all true. George is nothing like me. He’s worse. I suffer the indignity of him telling me he is not my slave every time I ask him to pass the salt.’

‘What do you do when he behaves like that?’

‘I usually say to him,’ When are you go…’

‘Go on,’ George replies.

‘When are you going to let me finish my questions?’

Do you listen to what your father tells you, George?’ I asked him.

‘Always. Dad was complaining last night that I never listen to him. Or something like that…’

‘ George is clearly an intelligent boy, Mr. Ramsbottom, I told the dad. ‘He has his moments but he’s not applying himself consistently. He’s often lost in hs own thoughts. He learns the material I prepare only when the spirit moves him. How do you explain his slap happy behaviour?’

‘I’ve raised him as an only child, which has really brassed-off his sister. My overriding aim now is for him at least to get a better job than I’ve ever had.’

When I asked George, a leaky fountain pen redecorating his clothes, what his father did for a living, he told me, ‘He plants chickens.’

‘You mean he plants vegetables, don’t you.’

‘He told me ‘chickens’.’

It turned out the father worked in a chicken plant. He smoked dope to handle the monotonous, infernal tedium and exasperation.

I said to the dad on parent teacher night, ‘How’s your family?’

‘I spend more time with the little birds. They don’t ask for so much.’

‘So you go running for the shelter of a father’s little helper.’

‘It helps me on my way, gets me through my long day pickin’ pullets.’

‘Aren’t you afraid you will become addicted?’

‘Cannabis isn’t habit forming. I should know, I’ve been taking it for years. And I only smoke it in the late evening. Or occasionally the early evening. Or occasionally the mid evening. That’s it. Except occasionally the early morning—or the mid morning. Maybe the late morning or the mid early late morning. But I assure you, never at dusk. That’s when the little weed fairies come.’

He asked me to help keep his lad in check. ‘Try to talk some sense into him. Mind you, he’ll try anything to put one over you. I won at the races and offered him ten pounds if he didn’t tell his sister. She disapproves of betting so I couldn’t offer her any. He said, ‘It’ll cost you more than that.’

He tells all kinds of porkies. He came home from school last week and said to me, “Dad, today in school I was punished for something that I didn’t do.”

I said, ‘But that’s terrible! I’m going to have a talk with your teacher about this … by the way, what was it that you didn’t do?’

George replied, “My homework.’

’I told the father, ‘I already brought this matter up with George. I said to him, ‘You haven’t turned in your essay.’

He replied, I’m no snitch. If you want a pigeon, go to the park. OK.’

‘Georgie speaks a lot about you.’

‘All good I hope. What kind of things does he say?

‘He says he told you if you gave him ten pounds he’d be good.’

‘He did that. And what did he tell you was my reply?’

‘He told me you said, ‘When I was your age I was good for nothing.’

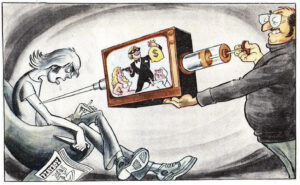

The kid was the kind who’d give an aspirin a migraine. The kind you’d send to the fish and chips shop and you’d expect no chips left when he got home. It did his father’s head in. The father put it down to him watching too much telly.

I said to him, ‘George, a word in your shell like ear. ‘TV is a narcotic. Do you want me to paint you a picture? It induces fake dreams. It induces lazy habits. Many of it’s programs are rubbish.

It drains away your manhood if you watch it all the time. This drug of the nation breeds ignorance and feeds radiation.

You’re also sitting too close. Look at your eyes, they’re turning into headlights.’

‘I flip through all of the channels. And still there’s nothing worth watching. But it gives me phone numbers to ring. OK.’

‘That doesn’t sound such a good idea. I have to advise you against it. That doesn’t mean you have to colour me a spoilsport.’

‘That’s alright, Mr. Davis. I don’t think of you at all. OK.’

‘George, Please stop saying “OK” all the time! OK?

‘OK.

‘Good.’

It’s believed his parents’ separation led to his naughtiness. One of the differences between his father and mother was over how he should be educated. His mother wanted him to be brought up at Eton. His father said: ‘Why go to that trouble? He already looks as if he’s been eaten and brought up.’

I asked Georgie was that the only reason behind the separation. He told me, ‘When I was in primary school, I asked my mum what a couple was and she said, ‘Oh, two or three’. And she wondered why her marriage didn’t work.’

His phone pranks started when he was in primary school. So as to extend his field of attack he had yet to brush up his act.

‘You say George has a cold and can’t come to school today? said the school secretary to the voice on the other line. ‘To whom am I speaking?

The other voice replied, ‘This is my father.’

‘You’ll have to do better than that,’ I warned the cheeky chappy, ‘It’s the little things that get you caught.’

In secondary school, he upped his mischief with the corny call, ‘Is your fridge running?’

With the phone balanced between the shoulder of one arm and ear, his mates gathered around him, he’d put his other arm on their shoulders. He’d be answered predictably by someone at the other end of the line caught unaware answering affirmatively. George and his gang got the satisfaction of getting to drop the “Well, you better go catch it!” before banging down the receiver and cackling away into the sunset.

‘Do you have pickled pigs feet?’

Having recently got some from the butchery, some unsuspecting respondent would eventually reply, ‘I do.’

George then offered, ‘Just keep your shoes on and maybe no one will notice,’ whilst becoming the centre of attention among his peers.

Another of his exhibitionistic tricks was to pretend to be from the telephone company and try to get the answerer to do something, like blow in the phone to “fix” it.

In one variation, George warned them not to answer the phone for fifteen minutes “because if they did, the telephone repairman would receive a fatal shock. Then he called over and over again in the next fifteen minutes, and if they answered he let go a blood curdling scream.

In executing this prank, he was able to assume a position of authority, make demands and have the majority of these demands carried out. This was particularly satisfying for kids, who usually carry out adults’ demands.

For George and his low stakes rebels, it was a chance to embarrass without retaliation the adults that in the normal run of things had power over them.

‘You know, we have something in common,’ he would put on the person on the other line, ‘You don’t know know what I’m going to say next and neither do I.’

George was in the habit of being late for school or bunking it.

‘What’s your excuse today?’ The Headmaster asked him one day when George arrived at lunchtime.

‘I was kicking the ball around in the park and lost track of time.’

‘So you suddenly decided to become an idiot.’

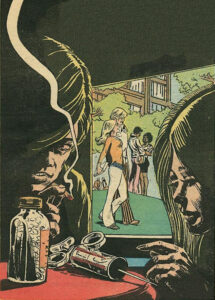

One day he skipped lessons and went to a strip club in Soho.

When word got to the principal he said to George, ‘ ‘A little bird told me you’ve been to the red light area. I’ve got a good mind to inform your father about that. Did you have a good reason for having been there, boyo?’

When George shrugged his shoulders, he asked, ‘Did you have a bad reason?’

Worried as to the effect of this exposure, The principal asked , ‘George, Did you see anything there that you were not supposed to see?’

‘Yes, I saw my dad.’

One morning he arrived at class well into term and well after the morning bell went. As usual he was on his own clock.

‘ Ah you’ve decided to grace us with your presence. Wonders will never cease. I’m sure we’re all thrilled to have our little lost lamb among us again as we begin this great second term adventure. Drum roll, please. However, I had hoped you were turning a corner in your attitude, George. Your father wants you to do well rather than coast along. He wants you to stop smoking for his sake.’

‘I don’t do it for his sake. I do it for my own sake.’

‘George, I want you to sort yourself out, to rise above your name, to act your age.’

‘I don’t know how to act my age. I’ve never been this old before.’

‘You have to consider your father and do what he asks you to do. Are you receiving me?’

‘What of it, I don’t have to jump every time he snaps his fingers.’

‘The same goes for these people you phone many of whom are seniors. You have to have respect for your elders.’

‘Who do you think I’m living with ,a Navajo tribe?’

‘Whenever your name comes up, students ask me, ‘George Who?’ Who is this George?’ Why are you late this time?’

‘My dad lost a ten pound note.’

‘This makes sense now. So you were helping him look for it?’

‘No. I was standing on it.’

‘Aren’t you being rather mean to your dad?’

‘Last week he said to me, ‘Here’s five pounds – don’t tell your sister,’

I said ‘why not?’

‘She’d say ‘it’s hers’.’

You should be more respectful to your father by being punctual. He has made a lot of sacrifices for you,’ I said.

That’s easy for him what with his religious beliefs. He’s a druid.’

By the way, what did you do with the ten pound note?’

‘On the way to school I came across a homeless man begging, Knowing full well this money would be used for buying drugs, I thought ‘What should I do?’ So I gave it to him.’

‘If ever you’re late again, make sure you have the right kind of note. It had better be good. You don’t want detention, do you?’

The next time he did have a note. ‘There’s a sort of greatness to your lateness. What’s your sob story this time?’ I asked. ‘Don’t tell me. You took the scenic route?’

‘My bus was delayed. You know what I mean. I waited for it so long, someone just stapled this to my chest.’

I looked at the flyer. Giving phone details underneath, it read in bold letters, ‘Have you seen our cat ?’

‘A likely story! Is that the best you can come up with? Having had to ring his home several times to check on his whereabouts I said, ‘Hey isn’t that your home number?’

‘Is it? I forget. I don’t call myself that often.’

Then he got taken in himself. One day he read in a flyer, ‘Send me ten pounds and I’ll tell you how to make money. He sent the writer the amount asked for. He got a postcard back that said, ‘Thanks for the tenner. This is how I make money.’

The next time he was late, I realised his social consciousness was coming along all too slowly.

‘So what was it today? For whom did the bell toll this time?’ I asked.

‘I had to ring 999 on my way.’

‘The emergency number?’

‘That’s the one. I had to wait twenty minutes to get through. When at last someone answered, I asked them ‘What’s the big hold up? I was just about to hang up. You’re very, very lucky this is a hoax’.

The next time late he rushed in puffing and talking too quickly.

‘Pump those brakes, son,’ I said, ‘You’re talking far too fast.’

‘You’re not listening quickly enough, Sir.’

‘No one’s rushing you to say anything. Now explain yourself in your own time.’

His excuse turned out as follows: ‘On the way here on the bus I seen a sign that said, ‘Have you seen this man?’

So I got off right away, called from a pay phone and said, ‘No.’

‘ Oh come on, that’s yet more waste of people’s time. Yours and that of others who’ve got important things to do.’

‘That’s just what the guy at the bookshop said after I rang it. He asked, ‘Can I help you?’

I said, ‘No thanks, I’m just browsing.’

‘‘Oh my days, George, a complete list of your indiscretions would make a best seller. Unfortunately they could be seen as harassment or interference. You might get rumbled. However, it’s never too late to mend your ways..’

‘I’ll think about it.’

‘Thinking is for those who have a choice. You don’t. You’d better outgrow your habit of making unsolicited calls.’

‘So I’m told. The last time I rang the phone service, I said, ‘I want to report a nuisance caller’.

Getting the hump, the operator cried, ‘Not you again’.

Another time he rang asking for directory assistance. Hello operator, I would the telephone number for Tommy Bragg in Birmingham.’

There are multiple listings for T. Bragg in Birmingham,’ replied the operator. Do you have a street name?’

He hesitated and then said triumphantly, as if he expected a gold star on his report card, ‘Well most people call me ‘The Telephonic Terror’.

‘What about T.A. Bragg?’ he went on.

‘That number I can give you. It’s Bir 123.’

‘I think I can remember that.’

Are you sure? Would you like me to write it down and send it to you?’

When those he phoned insisted on picking up the receiver and saying their home number, he would ask ‘Why are you doing that?’ What a complete waste of time. 020766944! I know that, I’ve just dialled it! The last thing I did on earth was dial those numbers. Do you open the front door and say your address? It’s the same principle.’

He rang the school several times to report sick. After this eventually proved unconvincing, he called in dead.

This quirk of his was eventually brought to a halt. He had started reversing the charges.

One guy he’d been pestering once too often now had his number and rang George: ‘So you’re the bloke who’s been wasting my time. Well whatever you’re playing at, the game’s up. I could smash your bloody head in.’

‘You wish to make an appointment?’ replied George.

‘What?’

‘I have some time on Saturday afternoon if that is convenient for you.’

‘You’d be laughing on the other side of your face when I’ve finished with you!’

‘Ah, the Resurrection! Where’s your homework? I asked him when he reappeared once. ‘This is a requirement, not a request .’ I knew he didn’t have a dog so he couldn’t claim it had eaten it. This was the reason he gave.

‘As I was leaving home this morning, I said to myself, ‘the last thing you must do is forget your homework.’ And sure enough, as I left the house this morning, the last thing I did was to forget my homework.’

‘What do you want me to do to remind you – write it on your forehead?’

At last he brought in his take away assignment completed perfectly.

I say, George do you mind if I ask you how you came up with such a great effort.’

Mr. Davis we just had a burglar drop in. When we got back we found little taken – we have little to take – but my homework completed and our furniture rearranged.’

‘That’s weird. What did the police have to say?

‘Their theory is the intruder is a a gay Asian.’

‘All right. You have two hours.’ I announced to him and his class at exam time,

‘Please turn over your paper and begin.’

All those hold ups in his classes led to George falling behind. I asked him why he had failed in mathematics.

‘I hate maths,’ he said. I wanted to fail. Everyone tells me I’ll never be a success, so why not?’

‘Think about the consequences, Georgie. If you try to fail, and succeed, which have you done?’

He fell into the temptation of cheating – unsuccessfully I might add. I had expected him to come through in his English test, his best subject, but it turned out otherwise.

‘Why did you get such a low score?’ I asked him after marking was complete.

‘Absence.’

‘But that was one day I remember clearly you weren’t absent.’

‘I wasn’t, but the boy who sits next to me was.’

Before another exam, Georgie and a friend decided to go to peep shows in Soho. They were having such a good time they decided not to worry about the English exam that they had scheduled for that afternoon. Called onto the carpet, they decided to tell the deputy principal that their bus got a flat tyre and if they could therefore take the exam at a rescheduled time.

‘Not you two again, ’he said to them, ‘birds of a feather. Well you won’t be hatching anything here. The jig is up. Is that nicotine stains on your fingers, George? I hope not. Now tell me the truth. I don’t want any tears, I don’t want any lies. Above all, I don’t want no alibis. So get your story straight.’

Hearing their brief explanation over again , the deputy wondered at first if this pair of brass necks were pulling his plonker.

‘Some story that is. You know that’s the third version you’ve told me. You’re a right one. Do you really expect me to fall for that?

‘What do you expect? ‘Gone with the Wind’?’

Then the deputy gave them the benefit of the doubt and accepted that it really was just bad luck, and of course they could take the exam later. At the appointed time, the deputy greeted them and placed them in two separate rooms to take the exam.

The few questions on the first page were worth a minor percentage of the overall grade, and were quite easy. Each student grows progressively confident as they took the test, sure that they have gotten away with fooling the deputy. However, when they turned to the second page they discover that they really hadn’t.

The only question on the page, worth most of the exam, read: ‘Which tyre was flat?’

Seeing him let down by his failure, I advised him, ‘Try harder and resist temptation to do the wrong thing, there’s a good lad.’

‘That won’t be a clean break. I’d like to be delivered from temptation but would like it to keep in touch.’

After I finished supervision of another test in which he looked furtively beside him, I brought up my suspicions to him: ‘I hope I didn’t see you looking at Brian’s exam paper ?

‘I hope you didn’t either..’

‘You mind yourself. You don’t know enough yet to know better. Always remember that during exams you are permitted to look down for inspiration and up in exasperation, but you are not permitted to look side to side for information. What have you got to say for yourself? Were the exam questions so difficult?’

‘They weren’t tricky at all,’ he replied. ‘It was the answers that gave me all the trouble.’

‘Please George, be a good boy. Listen to what I tell you. Don’t be pig-headed. Use your loaf and follow the regulations for exams.

He walked into a final exam very nervous. But when he received the test, he was relieved to find out that it was a True or False exam. Immediately, he reached into his pocket and pulled out a coin. Each time he flipped the coin he would write down an answer.

‘What are you doing?’ I asked him.

‘I’m figuring out the answers,’ he replied.

I remarked to him, ‘You know, Georgy Porgy, I really miss you doing everything you’re told.’

He looked at me quizzically, ‘but I’ve never done everything I’m told.’

I nodded and replied: ‘Yes, I know. I just said that I missed it.’

‘Mr. Davis. I can’t change the way I am. I always leap before I look. It’s too late to turn around. As my friends tell me, I have to be myself.’

‘Anyone who tells you to be yourself couldn’t give you any worse advice. It wouldn’t do you any harm to be a little more hesitant before you take decisions.’

‘It’s too late for that. I used to think I could be indecisive, but now I’m not so sure. I’m afraid I just can’t change.’

‘You just won’t let go, huh? You’re like a dog with a Frisbee. Now be on your way.’

I never saw this young, thrill seeking hotspur again. A friend dared him to take part in a physical contest.

‘That would be unfair,’ said George full of boyish confidence.

‘Are you that afraid?’

‘Hah, I’ll show you!’

‘Pinky promise,’ said the friend, linking their little fingers together.

George did a stretch in hospital after that friend bet him he could lean farthest out a window: ‘Five pounds says I can bend better.’ George —the jammy blighter-won with an own goal.

‘What did he say before he went down?’

‘Hold my Coke and watch this.’

‘ Where was his head? What was he thinking?’ I asked another teacher.

‘He wasn’t thinking.’

When he finally returned to school his leg was in a cast.

I said to him, ‘You’ve had a bad break, George.’

He replied, ‘If it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have any luck at all.’

All the kids wrote on the plaster.

His cousin wrote ‘Do you know how hard it is telling people we’re related?’ He was adding insult to injury.

The Primaries.

For a break I plumped for working in primary schools. They were easier to handle discipline wise, needless to say. I encouraged the small ones to regard learning as a voyage of discovery that, with me as helmsman, would take them to other places and parts of of the the natural world.

I could cover for other teachers on a short term basis easily enough, but after a spell my box of tricks was empty and I started to run out of hocus pocus, I was less of a novelty and moved on. It didn’t take long to learn the ropes in a new school. By and large these schools were remarkably uniform from the range of personalities among the teachers, to the books and materials available. I’d walk into a school, along the freshly mopped corridors, smell that institutional smell of the tomato soup, peanut butter, disinfectant, and boys room. Past the lunchrooms I’d see the familiar lunchroom ladies with nets on their hair.

‘School Dinners,

School Dinners.

Concrete chips

concrete chips.

Semolina pudding,

Semolina pudding.

I feel sick.

Bathroom quick’

Sung to the tune of Frere Jacques, this witty ditty was about something many found not so pretty.

The lunchtime meal which I shared, the main one for many, looked like feeding time at the zoo. All you needed was a chair to start with and bicarbonate of soda to finish. It sharpened the figurative powers of these young food critics.

‘‘Time for slops, Sir. Do you bags a spoon ? Or a hammer and chisel? I was asked. ‘I’ve got some in me schoolbag’ .

‘I’ve got some in my schoolbag,’ I corrected.

‘You still carry a schoolbag, Sir. At your age!’

The food got the kids creative juices going. The mince, knobbly mash or chips, soggy cabbage and mushy peas were followed by squidgy semolina pudding-called ‘gloop’. ‘clag’ or ‘wallpaper paste’ – with a blob of jam in the middle. Or glutinous sago pudding. ’Oh, goody,’ I would exclaim, ‘Frog spawn, the glue that holds us together. Now we’re really living!’

No one had to make up a novel name for ‘Spotted Dick’. Served with custard, it inspired the following question. ‘Why didn’t the Chinese invent custard, Sir?’

‘I give in.’

‘Chopsticks’.

‘And how do they eat when they’re on a diet?’

‘With just one chopstick.’

‘And with what do they feed their infants?’ I came back triumphantly.

‘Toothpicks.’

‘I must have Chinese in me,’ observed another, ‘I love it when we have rice. Rice is great if you’re really hungry and want to eat thousands of something.’

I asked one boy who lay his head down on the table looking at his plate with it’s cauliflower remainder.

‘What are you doing ? I asked him?

‘I’m imagining I’m up in the clouds.’

Simon said everyone had to finish what was dished out. And if they couldn’t, the leftovers were passed on to those odd Billy Bunters who would gorge themselves silly on anything. Like Oliver they couldn’t put their hand up for more. Seconds were not allowed.

Except when they were issued as a punishment.

You had to make sure you got your fill first time around.

“One serving lady asked a boy, ‘How many potatoes would you like, Tommy?’

He said ‘Ooh, I’ll just have one please.’

She said ‘It’s OK, you don’t have to be polite.’

‘Alright,’ he said, ‘I’ll just have one then, you silly moo.’

Those were the days my friend – before soft tissue. The toilet paper was waxed, smooth and shiny on the front and rough on the back, not what you would call absorbent. Choosing it was scraping the bottom of the barrel. Printed on each sheet was the reminder ‘Now wash your hands’. A cross between sandpaper and greaseproof paper, no-one would pilfer it. Ah well – all things bright and beautiful.

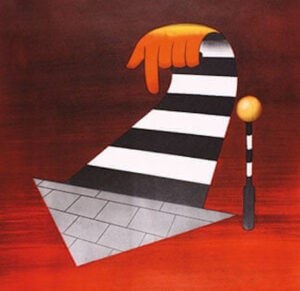

Outside the school, I was always impressed by the lollipop men and women, holding up their sign, shepherding the children safely across the road.

I reinforced their message in the classroom reminding the little ones to always look out for the guards and the zebra crossings.

In the fully asphalted playground I got to know the inner and outer workings of the British child. Skipping by themselves on the tarmac or using a longer rope while chanting skipping rhymes. They played chase and catch games, piggy in the middle and other ball games. What time is it Mr Wolf? hopscotch, farmer’s in his den, oranges and lemons and dipping rhymes to find out who would be “it” or “on”.

‘Would you like to play hide and seek?’ I was always invited.

‘I’m not very good at that, I think you’ll find.’

It is astonishing how varied forms of ball-play were. That simple piece of technology afforded kids fun in an apparently infinite number of ways by simply throwing, kicking, hitting, catching and bouncing a small spherical object. The mere presence of a ball of any size triggered the need to play.

One boy stood out for having positionings and movements designed for maximum soccer efficiency. I believed he could start his athletic career by becoming a ball boy. These teenagers are trained to supply the players with spare balls prior to loose balls being retrieved. The boys are typically positioned crouching behind advertising boards surrounding the football pitch.

I recommended to the principal he apply through the school for selection by tournaments.He had to go through to go through a number of selections and tests. These determine their fitness, endurance, their ability to concentrate and stay alert .

The children played lengthy series of games in which each has the hard shiny dark brown nut of a horse chestnut tree on the end of a string, each taking turns in trying to break another’s with it.

The fondness for the game would last a lifetime for some who improvise by smashing whatever’s at hand.

Are you planning to introduce this sport to the Olympics?’ I asked a group of children.

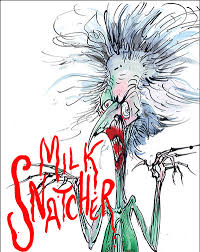

‘It’s our plan to conker Mrs. Thatcher.’

Death by a Thousand Cuts.

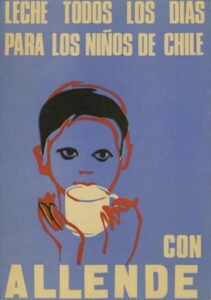

One day, I heard the children singing a new rhyme. Taunting the Education Secretary for cutting off their free milk, they chanted: “Mrs. Thatcher, milk snatcher!”

Sure enough this pillorying made it into the school concert with one of my classes overhauling the hit by Herman and The Hermits.

‘No milk today, she’s taken it away,

The bottles stand forlorn, a symbol of her scorn

No milk today, it seems a common sight

But children passing by, they know the reason why.’

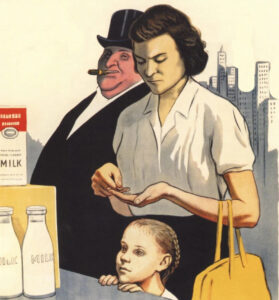

The issue was the loss of one of their benefits. And one of my daily duties. Escorting the children and lining them up to receive their third of a pint ration. Since the war, all milk toothed children had been provided with this in aid of their nutrition, as I had been back home.

Now Thatcher, the minister who’d become notorious for her public-spending cutting zeal had abolished free milk for schoolchildren aged seven to eleven.

She demonstrated overweening pride in weaning less affluent children off this nutrient rich food.

In one staffroom one of my colleagues held up a copy of The London Sunday Express. The headline read “The Lady Nobody Loves.” ‘Hardly surprising,’ he said. ‘Matron Thatcher’s a tight one if ever there was. How low can one go pinching pennies?’

‘Scrapping milk is the stingiest, most unworthy thing I’ve come across in all my years. This harpy holds that few children will suffer if schools are charged for milk. We’re not all shopkeepers. Has she ever seen how the other half live? For many of our pupils, it’s their only source of calcium. In terms of building bones it’s absolutely key.’

‘One child in three in our schools comes to school without breakfast.’ I said. ‘That glass of milk in the morning provides a much-needed fillip. There are so many pressures on parents and I think understanding from some parents about nutrition is so poor that many children are just not getting it.’

‘What she wants to evaporate completely is “a nutrient dense food”. It provides bushels of nutrients essential for growth, yet with relatively few calories. It’s the “original fast food”, being a quick and nutritious snack.’

‘Surely as a mother she would have gotten wise to this. As a chemist she did research on ice cream, I believe.’

‘Before making such hard policies, she worked on manufacturing such soft ice cream. It’s less dense than the more natural, adds air, lowers quality arguably and raises profits.’

‘That’s the political precipitate extracted. She’s not part of any solution.’

‘I don’t see better-off children running for Mr. Whippy. Children with the highest dairy intakes come from wealthier families and eat better diets overall. As a source of calcium, milk itself is the most practical one for children who do not get a balanced diet from foods like fish, fruit and vegetables.’ On the noticeboard in the staffroom was a picture of Mrs T. beside the phrase “Flying Start”. The first letter of each word had been crossed out.

‘That reminds me’, said my colleague. ‘There’s a joke doing the rounds where Thatcher is seated in a restaurant with a group of ‘wets’ from her department.’

‘Those she considers soft, indecisive and ineffectual. Broken reeds.’

‘Yes. Weak sisters lacking in bloodlust. The waiter recommends to Mrs. Thatcher, who is treating her minions to the meal, the ‘Soup de Jour’.

When she receives it almost immediately Mrs. Thatcher is a bit dismayed. “Good heavens,” she says, “ “What day is the soup from? And what kind is it?”

“Why, it’s bean soup.”

She replies. “I don’t care what it has been,” she sputters. “What is it now?”

She then makes the following resolution: ‘I’m sick of ‘Soup of the Day!’ It’s time we make a decision. I want to know what the soup from now on is.’

Asked what she would like as the main course, she replies: ‘Steak Tartare, please, fresh.’

‘Slay the beast, dehorn and mince it, then wheel it right in.’

The waiter replies. ’What about the vegetables?’

‘Oh, they’ll have the same as me.’

While waiting for the main course, Mrs. Thatcher’s choice of side dish, a Caesar salad is placed in front of her. As the waiter is walking away, she quickly calls him back to her table.

‘Please taste this salad.’ she says to him.

‘Why, Mam?’ asks the waiter. ‘Is there a problem with the salad? It’s the same salad you always have.’

‘Please taste it,’ she says again to him.

‘With all respect Mam, I can see nothing wrong with your salad. The lettuce and apple are fresh and crisp. The walnuts are top quality. It’s been prepared the same way we always do it .’

‘For the third time, Waiter, I ask you to please taste the salad,’ says Thatcher.

‘All right then… if you insist, he says, looking around the table, ‘but where’s the knife and fork?’

‘Ah hah,’ shouts Thatcher with a big smile on her face. ‘Set the table properly, Waiter. It’s not rocket salad.’

Procuring the beef for her and preparing it on the hoof proved a huge challenge for the restaurateur. ’How would you like it prepared? He asked the Minister.

‘Just tell the beast it’s going to die.’

The restaurateur got his kitchen hand to drive all the way to an abattoir to get the required order.

Becoming rather impatient, Mrs Thatcher said meanwhile , ‘Where is that waiter of ours? Has he died or something?’

After he came up at last with the goods, Mrs. Thatcher complimented him on her meal. The restaurateur replied. ‘Oh that just the regular steak tartare we serve here every day.’

‘What!’ thundered Mrs. Thatcher, ‘you mean to say you don’t serve anything special when the Minister of Education comes to dine?’

After the meal was over the waiter laid the check on the table and hovered around expectantly. He had refrained from turning on the charm, had remained consistent throughout his service and was now trying carefully to make eye contact.

‘You can clear the table now,’ said the Honourable Minister, ‘We’ll settle up at the register. What are you waiting for?

‘I was hoping for a tip,’ confided the waiter quietly.

‘Do you think money grows on a tray? Well here’s a good tip. Get a better paid job!’

‘Attila the Hen mightn’t like any additions to her own basic food prices but she wants to jack up charges for school meals.’

I said facetiously ‘I’ve heard she wants to have printed on each sheet of government issue toilet paper: ‘ Use both sides’.

I hear she wants schools to start using old newspapers like we did during the war,’ added one older teacher. ‘The Times are rough!’

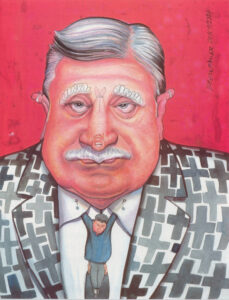

Her unacceptable decisions provoked a storm of protest from the Labour party and the press. My friend, geography teacher, Keith Morton commented ‘She’s bad news – Colonel Blimp with a handbag – the face of the growing reactionary ideological movement opposing Keynesian economics.’

‘It’s like a bad smell, it spreads,’ I said.

They actually believe it’s weakening Britain.’

‘Millions wouldn’t,’ I said. ‘People are very divided over her. Laud her or loathe her.’

‘How can they laud her? People weren’t inherently selfish in the postwar years. But now, many are becoming so.’

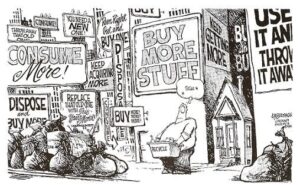

‘That tame aspiration of the fifties to “Keep Up with the Joneses” is giving way to an aggressive consumerism of a new and much uglier and more cynical strain. Mrs. Thatcher encourages that.’

‘Her reported comments don’t endear her to everyone. She was asked by one dowdy, roughly spoken party supporter, ‘Mrs. Thatcher, do you think English class barriers have broken down?’

‘Of course they have, otherwise I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to someone like you.’

‘Can I help you in any way during your electoral campaign?’

‘Yes, ’replied Her Haughtiness, concerned the lady would show her team up, ‘Stay at home.’

‘As a grocer’s son, Allan,’ asked Keith, ‘how do you feel towards the grocer’s daughter?’

‘She’s very shrewd, but also shrewish. She will mow down ideas, people and situations with a comment which holds no place for sentiment or human sensibilities. She is used to getting what she wants when she wants, brooking no wavering or opposition, She bases her activity on a clear, if narrow set of principles. She stands by them and does not duck or weave. She says “We must treat our adversaries as they are, not as we would like them to be.”’

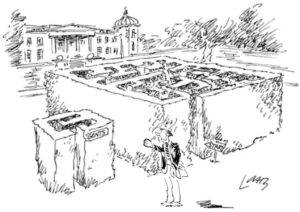

‘So let’s look at her ideas. She sees society as no more than an assortment of self seeking individuals – the most intelligent of whom, like the cream in her coffee, rise to the top.’

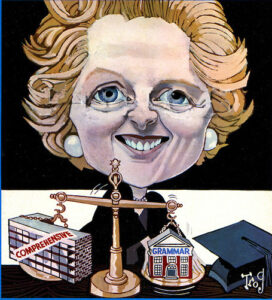

‘By tipping the balance of funding towards grammar schools at the expense of comprehensive schools, she can facilitate this.’

‘I know. And she expects us to be entrepreneurial. We could practice like lawyers, put up a brass plate in front of our houses and wait for clients.’

‘Yes I’m sure all the street children would queue up. Obviously this appeals to her Low Tory constituents – the nouveau or not-so-nouveau riche, those in trade, self-made men and women who work for a living in industry, publishing, marketing, City of London finance, the sort who buy their own furniture as opposed to inheriting it.’

‘ Self made men and women who worship their creator. And who just coincidentally think their wealth and rank derives from their congenital intellectual superiority.’

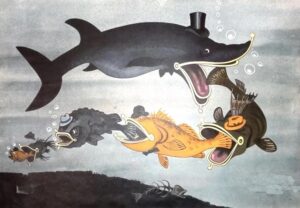

‘They believe that they are genetically constructed to be greedy, or as some call it, ‘financially ambitious’. This quality isn’t just good. It’s unavoidable. They believe they were born with their predatory instinct to accumulate which is healthy and natural.

The weak exist to be devoured by the strong.’

‘Sharks are born swimming, aren’t they.’

‘And they are not past consuming the suckerfish who keep them clean.’

‘Financial ambition is the mental engine that powers the world. Without it we would go back hundreds of years in time. Without capitalists our standard of living would be much lower. It’s what separates us from the animals. An animal just wants food for a few days or to last through winter. Man is the only species that can project the idea of the future.’

‘We understand that a life isn’t limited to a few days. It’s years and we have to make that life good for all it’s worth. We’re also the only ones who can imagine our own deaths. This leads to an existential anxiety which gives us a need to compensate. And because we understand that we can’t avoid our own mortality, it’s more important for us than any other species to enjoy our time here. And those of us go-getters with the best financial ambitions drag the others along.’

‘What if those others just have social ambitions and want to enjoy their time being happy with their friends?’

‘How necessary are friends? You don’t have to outswim sharks, only the friends you are skin diving with.’

‘How does that attitude bring society forward?’

‘You don’t make friends stepping over others on their way up but you can contribute to making the world a better place to be. Without this financial ambition students wouldn’t need to try their very best. People wouldn’t need to go to work or develop technology.’

‘You snooze, you lose.’

‘ Exactly. if you do not pay attention and do something quickly, someone else will profit. Money will allow you to do finally exactly what you want to do. So when people talk about capitalism with contempt, they have to think about it. Whether you like it or not, capitalism can’t be judged by motives. It can only be judged by the rewards it has given us. Not just as individuals but as a species.’

‘The ‘self made’ also believe they got where they are through hard work.’

‘When a man tells you that he got rich through hard work, ask him: Whose? To live you have to work, to get rich you have to do something else.’

‘ Yes, and we know what involves. Behind every great fortune is an equally great crime. Just remember the sweat and blood wrung out of working people to raise the level of wealth of such individuals as Krupp, Rothschild, Lady Astor, Du Pont, Rockefeller, Mellon, Ford and Harriman.’

They were against equality in every shape and form.’

‘ Thatcher, their greatest admirer. thinks the emphasis on equality of access to education brings everyone down to the same mediocre level. She has an abiding hatred of those teachers who she says ‘pound’ every ‘decent value’ out of students’ minds, of ‘trendy’, woolly minded teachers who don’t inculcate the three Rs. That’s when standards slip. She says socialists think if you’ve got any brains, you can’t show it ‘cos that’ll put other people off. I think myself if you’ve got any brains, rather than boasting of it, you should use them to bring others up to your level.’

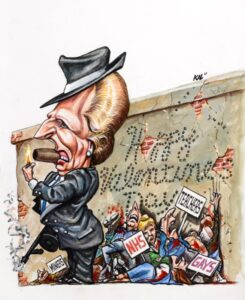

‘She’s certainly spoiling for a scrap. ‘I’ll give them the old one-two,’ she assures her followers, ‘I will, right up to the number ten!’ She’s going to impose savage public expenditure cuts on the state education system – not just nips and cuts.

She sees government regulation and what she sees as confiscatory taxation as neutering the animal spirits of capitalism.

‘This is a gross injustice to animals, who generally protect their own species.’

She doesn’t hide her ambitions for the top job. She calls her mission one of ‘national recovery’. To comfort the comfortable and to afflict the afflicted. This is how she wants to make Britain ‘great again’.

If she ever makes it to Number 10, others on her hit list will include health workers and the miners.

‘Surely she she would expect to outrage many people by acting so.’

‘She is prepared to ram through her controversial scheme without regard to others’ feelings. She has no concept of what she might be doing to others . I believe she’s entirely devoid of empathy. And so, she doesn’t try to disguise her agenda. She doesn’t try to wrap it up in platitudes. For her business is business. If people object it’ll be a case of ‘Off with their heads!’ Begrudgers like her know the cost of everything and the true value of nothing. She keeps the best whisky in her antique cabinet. ‘Let them eat cake’ she says – just like Marie Antoinette.’

‘What message is she and her fellow ideologues sending people? I asked.

‘She’s telling the masses: ‘Lock your doors, turn the other cheek, tug your forelocks, doff your caps. Money is the key to end all your woes, your ups, your downs, your highs, your lows. She’s telling them: Improve your life by yourselves, fend for yourselves, dig for your dinner, don’t rely on the government. Do your own thing. Pull yourselves up like I’ve done.’

‘It’s convenient for her to overlook that not all women are blessed with the privileges that had been available to her. She has domestic help and a wealthy and supportive husband who’s given her a hand up.’

‘The Good Lord will help those who help themselves. Socialism saps the foundations of our society.’

‘The barbarians are waiting outside with chaos, anarchy, and worse!’

‘Socialism promotes a false sense of equality,’ he said, taking off the Iron Maiden, his mouth puckered into a rosebud of disapproval. ‘It makes it impossible for the country to get anything really done. It undermines the rewarding of ability and exertion. It makes it so people lack respect for their betters. People must do what they need to do to get what they want. Being enterprising means making moves. Many employees want someone else to do what they should be doing. Macmillan said they’ve never had it so good. The fact is they have it far too good.’

And yet they tear down our efforts to create a better Britain-anything we ever build or achieve, anything with the slightest whiff of magnificence. As for themselves they make everything so second-rate.’

‘What do you put that down to?’

‘They don’t follow the accepted set of rules. Discipline’s gone. You’ve just got to look at the National Health Service. Any malingering snowflake without any redeeming defects can knock on a doctor’s door, moan, ‘I’m sick. Please treat me,’ and be issued a sick note automatically. Bosh! The state doesn’t exist to mollycoddle their weaknesses.’

‘What kind of state would you like to see ?’

‘One in which the people are led by someone strong. When you’re dealing with mediocre people, you need to govern them with a strong hand.’

‘What should the state do to restore the health of the NHS and other public enterprise operations?’

‘They have to be severely excised. The medicine is harsh. but the patient requires it in order to live. People think they have the right to live forever in perfect health at the taxpayers expense: ‘Doctor please, some more of these,’ while outside his door, these frequent flyers take even more.’

‘Not that the doctors are much better. Do you know how many doctors work in the NHS? Half. Do you know an NHS medico can earn in a year what it takes a chartered accountant to earn in a whole week. Common sense tells us people must put their shoulders to the wheel.’

‘But it must pay’, she doesn’t stop saying. ‘It must be rewarded so enterprising individuals enjoy the fruits of their labour. You know when a wealthy man walks into a room he knows exactly what everyone’s looking at, and he knows exactly what they want. So when did it become a crime to succeed in this country? Britain used to salute the successful swell in the Rolls Royce. They wanted to be the swell in the Rolls Royce. They still want to. But now they scratch the Rolls’ body with keys and coins. ‘

‘So how can they expect to make it themselves?’

‘Every earner should be an owner. There is no alternative. Hard work pays off in the future for those who abide by and uphold the laws of the land, without which, I should add, we are beasts that want discourse of reason. For those chasing their own tails, those whom it’s fashionable to call the disaffected and disadvantaged, laziness pays off now.

These skivers like to warm up their seats.

It’s because of all those union rules. We all know their motto: ‘Never put off ’til tomorrow what you can avoid altogether.’

‘These slackers, dossers and double dippers are disinclined to take responsibility for their actions and their lives. They think they’re hard done by. These sad little people moan, ‘I’m poor. Then the government tells them, they’re not poor, they’re needy. Then it tells them it’s self-defeating to think of themselves as needy. They’re deprived. Then it tells them that this term is overused, that what they are really are is underprivileged. How moving. The poor things.’

‘They still remain indigent but at least are provided with a voluminous vocabulary.’ I commented.

‘Even then they’re not satisfied. They whinge, ‘I have a problem, it’s the Government’s job to cope with it!’ or ‘I have a problem, I will go and get a grant to cope with it!’ ‘I am homeless, the Government must house me!’ They don’t look after the homes they’re already in. They leave their Council estates in such a mess throwing rubbish everywhere. They’re trashing the whole country.

But of course they say it’s not their problem. It’s someone else’s. The government’s. These parasites have been given everything.’

‘It’s the old shame and blame game aimed at those who fall short.’

‘All these loungers can do is take, take, take and contribute nothing to the community. ‘What’s yours is mine. Excuse me while I help myself.’ They think money from the Exchequer grows on trees. They think pennies fall from heaven. They don’t. They have to be earned here on earth. Can you blame them when Labour has never stopped it’s profligate distribution of public monies raised from taxes and rates?’

‘For some in the very prime and flower of their youth, getting out of bed in the morning is a career move. They live in the government’s basement, focussing their energies on obtaining a larger allowance rather than getting a job and moving out. These malcontents, unsatisfied with their miserable existence, spend half their day loafing in bed and the remainder selling, using drugs and stealing from each other.’

‘They’re too gutless to go out and make money for themselves honestly. Everything’s been given to these useless creatures, yet they’re never satisfied. What will they want next? First they whine saying they must have more leisure. Now these moaning minnies are complaining they are unemployed.’

‘The socialist ‘nanny state’ robs people of initiative. It penalises talent and industry. It’s debilitating culture of dependency robs people of responsibility. They become like sheep.’

‘There to be led astray and stripped of their coats.’

‘If God didn’t want them shorn, he would not have made them sheep. They think they’ll prevail because there’s more of them. The world’s about winners and losers. Only one in a hundred of those losers is going to get on that ark. The rest of those poor wretches are going to drown. Listen, the plebs don’t grant the least value to work. That’s not sweat on their palms it’s envy, it’s resentment. If you want to live in this country, you must pay for the privilege.’

‘We all have to pay our way in life, to make our own place in the world. It’s like good housekeeping. Bills have to be paid and books have to be balanced. When I’m short one week I have to make economies the next. This state wants to change our time zone. At 9AM every Friday the clocks would go forward eight hours. What I want to say to workers is otherwise, ‘If you’re on time, you’re too late. ’Their job is to be in front and look into the future. They need bosses who will never be envious when they make a fortune. It’s the opposite. The real boss will push them to get as much as possible out of it. Not just for his sake but for everybody’s. He won’t come from the public sector. This state drives a great many of our decent men and women to to get a good little earner, to do a bit ‘on the side’ to avoid taxation. And the worst sin of all. It disrupts the market.’

‘Rhubarb, rhubarb, we’ve heard it all before,’ I said, taking over from Keith. ‘The world doesn’t owe you a living. You’re on your own. Every man and his dog for themselves. Life wasn’t meant to be easy. We all have to find our own way in the world. There’s no such thing as a free lunch. The meek won’t inherit the earth. The winners take all. The market should have the final word on everything. Don’t expect something for nothing. Be like me. Me first,’ I said, thumping my chest.

‘Stop carrying the burden of the world yourself,’ said Keith raising and lowering his shoulders. Shrug this weight off like Atlas! Be self-reliant. Pull yourselves up by your bootstraps.’

‘’That’s an absurdity of course. The concept of bootstrapping is an impossibility. You cannot pull on — you can barely pull your boots on by your bootstraps; you certainly can’t pull yourself up by your bootstraps.’

‘Work for your own benefit, not that of others. Push down on them so you can rise up. Do only what is useful for yourself. Sacrifice nothing for others. That way you will ultimately create more value for the world. Then you’ll truly be Number One.’

‘He or she who thinks only of number one must remember, it is next to nothing.’

Then I could hear it, the Sound of Music spouting forth from within me. Not the light and fluffy movie but the satirical Broadway gem about egocentrism, amoral political compromising and sense of inevitability, all excised along with it’s class and political tensions.

The sound came from within me but not in the smoother, softer notes that Laurence Olivier would coach her to produce.

Perfectly adapting pitch, diction and delivery to suit a particular mood and role, Olivier’s voice was his not-so-secret weapon.

My sound came in the earlier strident, hectoring, piercing tones of the aspiring Tory grand dame. I went up an octave to put on the voice of a woman who sounded like she was putting on a voice, singing:

‘That all-absorbing character,

That fascinating creature,

That super special feature,

Me!

Why not learn to put your faith and reliance

On an obvious and simple fact of science?

Every star on every whirling planet

And every constellation in the sky

Revolves around the centre of the universe

That lovely thing called, I.

And there’s no way to stop it.

No, there’s no way to stop it,

And I know, though I cannot tell you why.

Just as long as I’m living,

Just as long as I’m living,

There’ll be nothing else as wonderful as I.

I! I! I!

Nothing else as wonderful as I!’

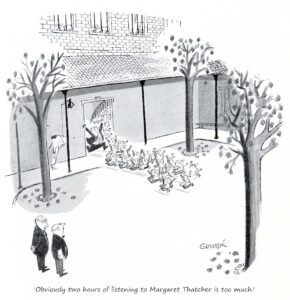

‘ For style I’d give you an Oscar, Allan.’ said Keith. ‘Her style of government,’ said Keith, ‘is similar to running a corner shop, a small business with balanced books, in which she says those who wish to beaver away 20 hours a day leave in the shade the inconstant, slothful sods who drag their feet. Giving an appearance of working 9 to 5. ‘Hard work never killed anybody’, she attributes to them, ‘but why be the first!?’ ‘why take the risk!?’ ‘If a job’s worth doing, it’s too hard’. ‘I just work here.’ ‘That’s the attitude.’ She sees the public service which delivers the protective social umbrella as an infernal nuisance. She never needed a social worker so why should anyone else: ‘We’ve become a nation of deserving cases’. She believes everyone should be able to run their own lives by themselves. She’s down on affirmative action. Her self centred approach is shaped by monetarist theorists from the other side of the pond. They reject Keynes’ theory about inflation. They argue it’s hardly worth anything now. ’

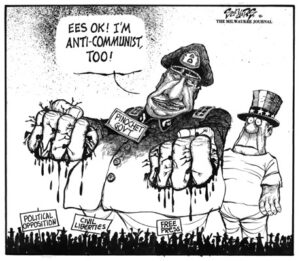

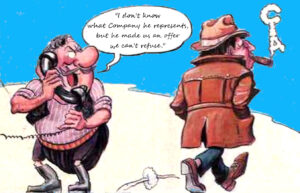

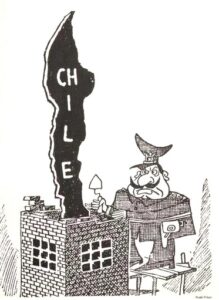

‘These monetarists are disciples of Milton Friedman who set out his ideas in ‘Capitalism and Freedom’. Describing Chile as an economic and political “miracle, they are applying their ideas in Chile now that Pinochet has U.S. backing .’

Milton Friedman met with Pinochet to convince him that Chile’s economy required ‘shock treatment,’ primarily in the form of a drastic reduction in public spending. The general, Friedman noted, “was sympathetically attracted to the idea of a shock treatment but was clearly distressed at the possible temporary unemployment that might be caused.” In the wake of his visit, Friedman wrote to Pinochet to stiffen his resolve: “There is no way to end the inflation that will not involve a temporary transitional period of severe difficulties, including unemployment.”

Friedman wrote to Pinochet to assure him that Allende’s government represented the “terrible climax” of a trend toward socialism, and that the general had been “extremely wise in adopting the many measures you have already taken to reverse this trend.” He and his fellow neoliberals helped devise Pinochet’s economic agenda and endorsed the brutal repression that was needed to force it through.

The neoliberals in Chile mobilized a stark dichotomy between politics as violent, coercive, and conflictual, and market relations as peaceful, voluntary, and mutually beneficial. It was in Chile that a neoliberal human rights discourse was consolidated. This neoliberal version of human rights justified constitutional restraints and law as necessary to preserve the individual freedom that only a competitive market could secure.

If human rights were a product of a functioning market, as the neoliberals consistently argued, they were also necessary to protect the market from egalitarian political movements. Rather than protecting individuals from state repression, neoliberal human rights operated primarily to preserve the market order by depoliticizing society and framing the margin of freedom compatible with submission to the market as the only possible freedom.

‘It’s an open secret that the CIA provided strike benefits and other means of support for anti‐Allende businesses.

The truck strike it subsidized seriously disrupted Chile’s economy.’

Thatcher believes to the contrary it was a small minority of communists who nearly wrecked Chile’s economy through their chaotic collectivism and that Pinochet stopped them setting up a dictatorship. She is convinced his regime is now building a prosperous, democratic country. The Lady believes she can learn from his example.’

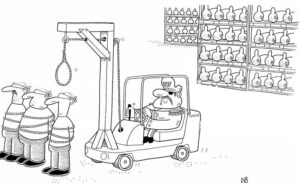

He would become what she’d call a ‘staunch true friend’. He might have violently overthrown the democratically elected government.

He might have quarantined the country from outside influence and prevented opponents departing.

He might have brutally tortured and murdered thousands of people, but he had a great grip on economics!

‘He has greatly accelerated disassembly line production rates.’

‘She’s heartless’, continued Keith. ‘She’s the kind of person that if you were drowning fifty feet off shore, she’d throw you a thirty foot rope. Then her publicist would go on TV the next night and say that she had met you more than half-way.’

‘Ethics teaches that virtue is its own reward, in monetarist economics we get taught that reward is its own virtue. To fit in with this they aim to bring in a host of big changes.’

‘Toll roads, electronic tagging of offenders, the privatisation of prisons, the return of ‘calm and sanity’, of capital punishment, the scrapping of the National Health Service, childcare provision, you name it’

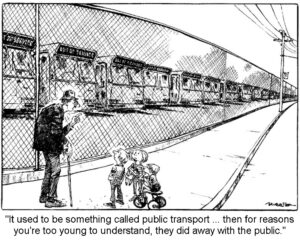

‘Her party has it’s sights set on the coal industry. Private operators will profited handsomely, but passengers dependent on buses to get to work, access services and visit loved ones will suffer greatly.

You mark my words, it’ll be privatizing the bloody air next. ‘Yes, hold your breath, Sir, that’s government property!’

‘She says if we don’t cut spending we will be bankrupt. She likens her cuts to harsh medicine which the patient requires in order to live.

She believes if workers are more insecure, that’s very healthy for the society, because if workers are insecure they won’t ask for wages, they won’t go on strike, they won’t call for benefits; they’ll serve the masters gladly and passively. And that’s optimal for corporations.’

‘They’re not worried about paying for somewhere to live ,are they?

‘She says the homeless should save to buy their own house.’

‘That figures. The last homeless person she had any time for was the baby Jesus.’

‘She says there’s no such thing as society. She’s sowing the seeds for the dismantling of the welfare state,’ I said, ‘and replacing it with an even colder tighter company rule. There’s no telling to where this is going to lead.’

‘Heads will roll. She and the monetarists want to build a New World Order. A citizens’ wasteland. No regard for the poor. No regard for the indigent. No one to pick up the slack for you if you get sick. Cater for those with deep pockets, keep the wealthy happy and the others—-?’ he said, stretching his arms outwards.

‘Punch down the vulnerable. Climb on their backs. Push them aside. But will it work?’

‘This might work well in a frontier society with boundless natural resources and no resistance from anyone but not here where most people hang their hats on selling their labour power. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and we as a country are only as strong as our poorest families. Unchecked, such politicians will destroy our social fabric and weaken the country. ‘

Mrs. Thatcher Bumps Into Me.

Mrs Thatcher visited several schools under her administration.

At some she was welcomed warmly . At others all didn’t go so smoothly. At one school I was at she chose to enter by the back door past dustbins and through the kitchens to avoid placard-waving student protesters.

Having gone to the kitchen to order my lunch, I found myself pressed against the scullery door as the Minister brushed hurriedly past me .

‘Excuse me, ’she cried out to me in that shrill, high pitched, strangulated voice she had before elocution lessons.

‘Be my guest…’ I said, giving way to her.

I recognised her from her wardrobe which had become her suit of armour at that time. The bright blue shift dress, the pearls and ear rings, that coiffed hair swept back from her face like a helmet, and the ever present square black handbag swinging from her gloved arm.

While the children found her talk rather long, at the end there was much whooping and cheering.

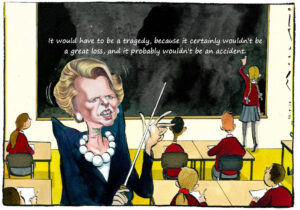

One of the many apocryphal stories going round the staffrooms was about the day when Attila was visiting one of the a junior secondary school under her administration. After the platinum blonde in the pussy bow blouse, garden-fête hat and chunky jewellery had talked down to the welcoming party, she was taken into the room of a class discussing words and their meanings. The teacher asked whether she would care to lead a discussion on the word ‘tragedy’, so she asked the class to give her an example.

A boy stood up, and said, ‘If my best friend was playing in the street, and a truck ran over him and killed him, that would be a tragedy’.

‘No,’ said Mrs. Thatcher, ‘that wouldn’t be a tragedy. That would be an accident’.

A girl raised her hand: ‘If the school bus had fifty boys and girls in it, and it drove over a cliff, killing everyone inside, that would be a tragedy’.

‘I’m afraid not,’ explained Mrs. Thatcher. ‘That is what we would call a loss of some proportion.’

The room went silent. No child volunteered.

Mrs. Thatcher’s eyes searched the room. “Can no one here give me an example of a tragedy? At the back of the room, a girl’s hand went up, and a quiet voice said, ‘If a plane carrying you and Mr Thatcher was struck by lightning and crashed, that would be a tragedy’.

‘Magnificent!’ exclaimed Mrs. Thatcher, ‘You’ve got it in one. And can you write on the blackboard why would that have to be a tragedy?’

‘Sort of,’ said the quiet voice as she commenced moving the chalk across the board.

The girl was living proof of the saying, ‘It’s always the quiet ones’.

Who would have known at that time that anyone would ever be so enraged as to consider putting the third possibility into operation at Brighton – and accepting responsibility.

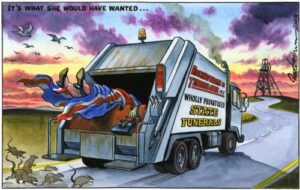

Upon her eventual death many would mourn and honour this privatising Queen of Hearts.

Many others would declare ‘good riddance to bad rubbish!’

I try to be very careful, very restrained, whenever somebody dies, independently of my opinion of the deceased, to respect the people who are in grief. I didn’t celebrate her passing but I’m under no illusion about the destructiveness of her policies and divisiveness of her legacy.

I excused her for my being pushed against the school’s kitchen door but her defence of Pinochet was inexcusable.

He not only did away with the distribution of free milk to schoolchildren. He did away with Salvador Allende who had brought in the scheme.

Now back to her attendance at the school. At the end of the visit Mrs. Thatcher and the children were all photographed, and she encouraged them each to buy a copy of the group picture. ‘Just think how nice it will be to look at it when you are all grown up and say, ‘There’s Mary. She’s a lawyer, ‘ or ‘that’s Peter. He’s a doctor.’

Then that small voice at the back of the room rang out, ‘And there’s Mrs. Thatcher. She’s dead.’

Two Different Worlds.

Most of the schools I worked at were in working class areas. I always learned something about the local customs and habits to make my lessons more meaningful.

To make addition simple and understandable I put it to one class, ‘ ‘If I have six bottles in one hand and five in the other hand, what do I have?’

The answer, ‘A drinking problem.’

At another school I incorporated the children’s love of pets into arithmetic. ‘ If I give you two rabbits,’ I asked one small boy, ‘ and then I give you another two rabbits, how many rabbits do you have?

‘ Five’ he answered.

‘ No, listen carefully again. If I give you two rabbits and then I give you another two rabbits, how many rabbits have you got?

‘Five.’

‘ Let’s try this another way. If I give you two guinea pigs and then I give you another two guinea pigs, how many guinea pigs have you got?

Paddy: Four.

‘Good! Now, if I give you two rabbits and then I give you another two rabbits, how many rabbits have you got?

‘Five,’ he insisted.

‘How on earth do you work out that two lots of two rabbits is five?’

‘ I’ve already got one rabbit at home, Sir.’

I learned of their most popular reading, one they really got their teeth into. Those sticks of sticky, sugary rock dreaded by dentists. A ring of bright red letters spelled out the name of the seaside resort where bought.

I asked a class to write a composition describing their seaside holiday. One pupil, a boy with badly chipped incisors delighted me by spelling ‘Weston- super- Mare’ correctly every time he used it.

Eventually I asked him to the front of the class and said, ‘Show the class how well you can spell, Tommy. Write ‘ Weston -super-Mare ‘ on the blackboard.’

‘Please, Sir, I can’t any more,’ he pleaded, ‘I’ve eaten all my souvenir rock.’

Some of the children needed help in writing more diplomatically what they wanted to say . One class were asked to write a piece about someone they knew from a tongue in cheek method. One boy wrote instead from a foot in mouth approach.

One school was located in an area called Worlds End, a pocket of poverty, little worried about being tidy and well-behaved enough for its trendier cousin, Chelsea.

I had to go to a school in Chelsea and was told it was near an upmarket pub. I asked the bus conductor when I got on, ‘Do you stop at ‘The Chelsea Potter’?’

He replied, ‘Not on my salary I don’t.’

In Chelsea they bought clothes described as ‘vintage’. In World’s End they were described as second hand.’

It’s houses brought to my mind the Pete Seeger ditty “Little Boxes’. These small single-storey cottages were built as temporary public housing stock after the Second World War during which the area was blitzed.