Perhaps we could have a translation, I could not quite follow.

Harold Macmillan, after Khrushchev banged his shoe on the desk at the United Nations

A Matter of Principle

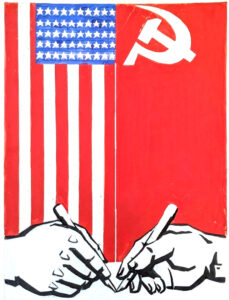

The global contest of ideology and power between the Soviet Union and the Western parliamentary democracies set the tone for the conduct of international relations during a large part of the twentieth century. For successive Western leaders it did much to establish the context within which their foreign policy had to be constructed and implemented. Many of them alternated between policies of confrontation and co-operation as they struggled to contain what they saw as the twin threats of Soviet power and Communist ideology, while maintaining a working relationship with the Soviet government.

After World War Two, British leaders had to consider the abandonment of armed intervention and the first unsuccessful attempt to draw the new Soviet state into the international world order. Churchill, his imagination fired throughout much of his political career by the threat and the challenge of Russia, moved from the anti-Bolshevik tirades of the twenties and thirties to the wartime military alliance, the sterile nuclear confrontation of the Cold War years and the final attempt to forge some new understanding after the death of Stalin.

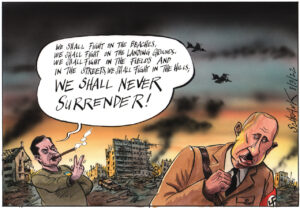

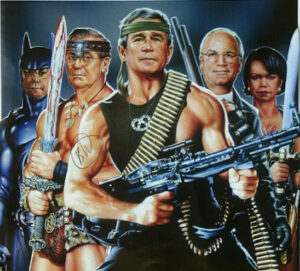

At the same time hardline Cold War politicians deployed the rhetorical device of comparing any adversary with the Nazi dictator for arrogating whatever extreme measures they wished to implement, including military action.

They conflate negotiations with appeasement as they do with post-Soviet Russia regarding it’s invasion of Ukraine.

Putin’s actions took them by surprise and appear to have been a spontaneous reaction to the coup against the pro-Russian government in Kiev.

Throughout the Cold War, the US defended its nuclear stand-off with the Soviet Union by constant references to the Hitler and Munich analogies although the Warsaw pact forces never expanded anywhere.

.It feared the Soviets appeared amenable to negotiations but really wanted to get the upper hand.

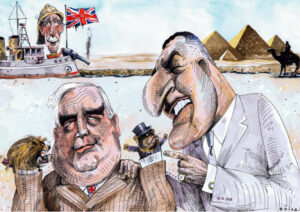

Claiming Egyptian leader Colonel Nasser was a new Hitler, the British, French, and Israelis occupied the Suez Canal in 1956.

I believe it’s always necessary for leaders to negotiate with their adversaries to avoid or stop hostilities. That includes Chamberlain’s daring flight to Munich to negotiate tensely, face to face with the moody, volatile Hitler.

No one could have foreseen the genocidal proportions of the man he called ‘The commonest little dog I have ever seen’.

Chamberlain’s mistake was to base his announcement on what might have been be pleasing to imagine and to go along with the strong popular sentiment against another devastating war. This, it was argued, lulled the populace into a false sense of security.

It can also be argued if the British and the French had gone to war earlier, Hitler might well have survived a lot longer and been much more triumphant.

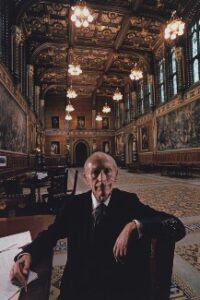

While reflecting on these matters of war and peace, I considered the experience of Harold Macmillan whose repugnance to war had been shaped by his baptism of fire in the trenches. His involvement in much of Britain’s decision making would reflect this. As a progressive back bench member of the House of Commons in 1930’s, he criticized Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and the Munich Settlement in 1938. He was one of the small group of Conservatives prepared to face political suicide for chivvying their government into changing it’s foreign policy. In particular they tried to persuade it to drop it’s quiescent acceptance of the Francoist forces in Spain and Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia – an issue on which Macmillan resigned from the parliamentary party. When sanctions against Italy were abandoned in 1936 he was one of only two conservatives to vote with the Labour opposition against the Government, supporting the motion ‘that His Majesty’s Government by their lack of a resolute and straight forward foreign policy, have lowered the prestige of the country, weakened the League of Nations, imperilled peace, and thereby forfeited the confidence of this House’.

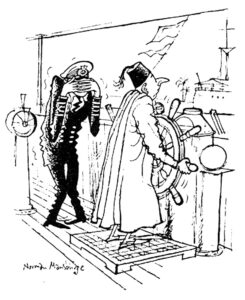

As Prime Minister between 1957 and 1963 he proved to be an extremely able diplomat gaining respect in Russia.

He helped considerably to lower the temperature of the rhetoric at the summit conference with Russia. This followed the U-2 incident in 1960 in which an American aircraft was shot down over Russia.

The first British prime minister to get to grips with sound-bites and photo opportunities, he had a penchant for the flamboyant. As well as flying off to meet up with leaders across the world in serious talks, nothing gave him more pleasure than singing and dancing with them.

The climax of Macmillan’s stylish performance came in his double act with President Kennedy, himself no stranger to razzmatazz. These personal touches, his nonchalant elegance, did more for Anglo-Soviet relations in minutes than diplomatic exchanges did in a month.

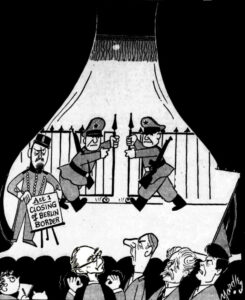

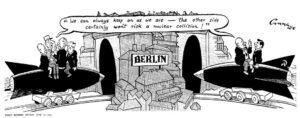

He took a pragmatic approach to the erection of the Berlin Wall, noting in his diary: “There is actually nothing illegal in the East Germans stopping the flow of refugees and putting themselves behind a still more rigid iron curtain. It certainly is not a very good advertisement for the benefits of Communism – but it is not (I believe) a breach of any of our agreements.”

The crisis found Macmillan, celebrating, as he did every summer, the opening of the grouse-shooting season.

He was engaged in appropriate use of firearms against indigenous bird-life rather than against the Soviet forces in Germany.

During discussions about contingency plans in case of another Soviet blockade of Berlin, Macmillan had declared rather sourly that Britain ‘should make it clear that we will pay nothing’ toward the expenses of any new airlift.

Suez And Beyond.

‘To my mind Britain, is exactly like the hypocritical school-master who says “this is going to hurt me more than it does you” and finds out to his horror that he is telling the truth. ’

Peter Ustinov on the plan to attack Egypt.

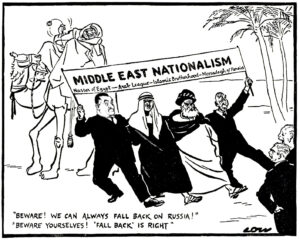

Mr Macmillan encouraged the move to independence among the former colonies in Africa in response to the rise of nationalist fervour. Of course it wasn’t out of the imperial powers’ kindness of heart. They had no choice but to let the colonies go. This was in case they fell into the ‘wrong hands’. In case they drove them into the Soviet camp.

I thanked him for his prudence in not allowing the crises over Suez and Berlin to get out of hand.

He backed Britain out of the joint military operation with the French to regain control of the Suez Canal . An ardent proponent of the adventure in 1956, It was he who pressed the financial necessity of bringing the operation to an end.

As Chancellor of the Exchequer, he had taken a fire-eating stand in urging the overthrow of Nasser. Daring to the point of recklessness, he was fascinated by the nature of the game down to the last throw of the dice. This error of judgement could have led to a nuclear confrontation. It had united the various Middle Eastern nationalist forces that he and his Prime Minister had discussed three years earlier..

Churchill had helped the Americans remove Mossadegh from the picture but then it was Nasser’s turn to upset the imperial apple cart. And this time the Americans weren’t going to get involved.

Robert Menzies had been chosen to lead a five-nation delegation to Cairo to negotiate with Nasser. However despite all his efforts to win over the Egyptian leader, his appeals were unsuccessful.

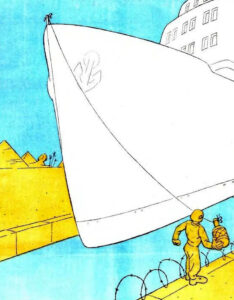

Under Nasserist rule, there was an expansion of the state sector which provided employment- a large army, an expansive bureaucracy , nationalized industries and construction of the Aswan Dam .All this needed funding and nationalizing the Canal, owned primarily by British and French shareholders, was Nasser’s solution.

The canal was strategically important as a conduit for the shipment of oil. France and Britain felt their supplies threatened.

There was an overriding concern that the Soviets were behind this.

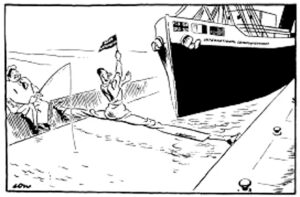

Before the Egyptian .forces were defeated, they had blocked the canal to all shipping.

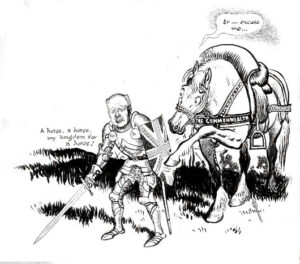

The decision over the Canal had led to the charge of the right brigade that his was a policy of cutting and running.

The decision over the Canal had led to the charge of the right brigade that his was a policy of cutting and running.

They could never accept the position of British as a second-rate power. For them Britain would always ‘stay in the big game’. They believed that only force, and nothing but force, is understood by the lesser peoples whom they ruled. In this game the Egyptians were seen as subordinate.

When the revolutionaries in Cairo dared to suggest that they would take charge of ‘ The Ditch’, the naked prejudice of the imperial era bubbled to the surface. The Egyptians, after all, were among the original targets of the epithet, “westernised (or wily) oriental gentlemen. They were the Wogs, regarded as too backward to operate the canal.

It was the Americans then, fearful of alienating Arab opinion, who were urging restraint and negotiations with the U. N. Posturing as friends of Arab nationalism, they tried to gain credit by disowning their belligerent junior allies. The crisis allowed them the opportunity to cosy up closer to Saudi Arabia.

The British cabinet conceded in private that Nasser’s action was technically legal – especially as he claimed he would reimburse the shareholders and Canal traffic flowed smoothly under Egyptian ownership.

I reminded Macmillan that the plan of invasion was contrary to the ideals that Britain said it was fighting for during the War-the rule of law and national self-determination. It was a violation of the U. N. Charter and all that Britain claimed to stand for. Of course, the Arab on the street and the new Commonwealth members understood that employing an Israeli strike force allowed a cover for the British and French ‘good guys’.

It allowed them to intervene as ‘peacemakers’ and force some sort of international control. The attack led to France and Britain being condemned at the United Nations, the Commonwealth cleaving along racial lines, and the Western alliance almost ripped apart. It was realization of all the opposition to this gunboat diplomacy as much as noble considerations that led to the plug being pulled.

Macmillan needed to have the Commonwealth more at his back, not on it.

India’s takeover of the Portuguese colonial enclave of Goa in presented Macmillan with another awkward situation. Jawaharlal Nehru had advised the big powers to abjure force and work towards disarmament but decided to use force to liberate Goa from its Portuguese colonialists. It was an agonising decision for a person who adopted the Gandhian approach in international affairs. Nehru justified his action using the UN, saying resolutions denouncing the Portuguese colonialism had passed in 1960 and 1961, asserted and legitimized Indian claim on Goa, arguing his action was a police action, national liberation, and not an international invasion.

Britain was pulled in two different directions. On one hand, it wanted to preserve its close long term alliance with Portugal, its fellow NATO member, and on the other didn’t want to be seen promoting colonialism. Britain also sympathized with the Indian cause and decided to stay neutral. Macmillan’s administration followed a policy of concerned detachment.

Macmillan, in his ‘Winds of Change’ address before South Africa’s parliament, in February 1960, had called for a more enlightened European response to the upsurge in the awareness of nationhood sweeping across Afro-Asia. As he put it that day: ‘The wind of change is blowing through this continent and, whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political fact’. The speech is today remembered as an official statement in support of the swift decolonization of the British Empire in Africa and a rebuke to the intransigence of white settler politics and South Africa’s system of apartheid. Britain wished other European powers to follow suit and give up their colonial possessions,

However Portugal rejected Macmillan’s counsel and retained its possessions. ‘It was absurd of the Portuguese’, Macmillan recorded, ‘to try to hold onto it [Goa]’. Canada, Australia and other Commonwealth members were also eager to maintain their relationship with India.

The Portuguese had appealed to Great Britain to bring pressure on India. Foreign secretary Alec Douglas-Home made it absolutely clear that the NATO alliance did not extend to Portuguese entanglements overseas, and that it should not expect anything more than a mediating role. He also warned that if Portugal invoked the old Anglo-Portuguese Alliance, Britain’s response would be constrained, as she had no intention of engaging in hostilities with a member of the Commonwealth. It had to contend with a Commonwealth that was determined to have the whip hand for once over ts former imperial master. It wanted an apology and a commitment to reparatory justice for Britain’s barbaric role in slavery and mistreatment of its colonial subjects.

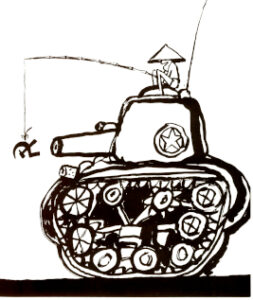

Mindful of Lisbon’s importance to NATO, Dean Rusk, Kennedy’s secretary of state, differed. He acceded to a Portuguese request that American officials refrain from any public comment on the colonial dimension of the Goa dispute. He issued the Indian government with a firm warning against launching a military assault on Goa. For the US however, Goa was ultimately too unimportant compared to the action in other places such as Indo-China .

Matchpoint.

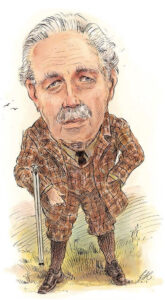

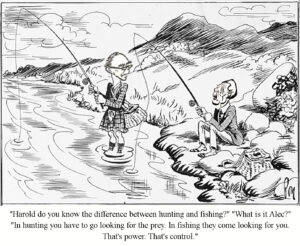

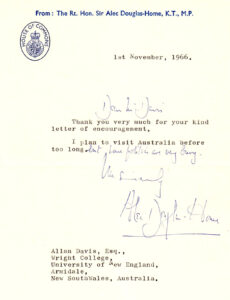

‘Grouse’, I said, writing to Macmillan’s anointed successor as Prime Minister, Alec Douglas-Home .

I meant ‘grouse’ in the Australian sense of ‘excellent’. This Tory grandee was to the manor born .

Unobtrusive and undemanding in manner, detached from normal party rivalries which his birth and training secured for him, he gave the impression of being ‘all of a piece’. Macmillan famously described Sir Alec to the Queen as ‘steel painted as wood’.

A great Scottish landowner, he was taken with the gentlemanly pursuits of hunting, shooting and fishing.

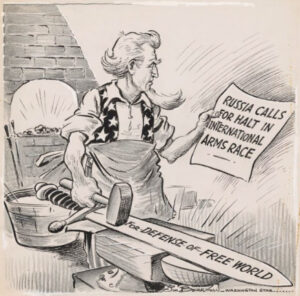

The grouse he stalked on the the fields and babbling brooks of the Scottish lowland moors were top of the range. Of the game this toothy somewhat mousy, serious outdoorsman hunted in , this was the one he most admired most: “… the mountain and moorland scenery in which the grouse lives is beautiful, romantic and often spectacular, while the challenge presented to the shooter is incomparable.” I wrote to him about the even more incomparable challenge presented to the shooter. Facing off much bigger game in a contest which we’d all quail at, I complimented him on working towards the signing of the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in Moscow in 1963.

Khruschev looked on as Home, the Soviet Foreign Minister and Dean Rusk ratified the Treaty.

The treaty retricted nuclear testing to those conducted underground.

Its success was limited by the reluctance of France and China to come on board.

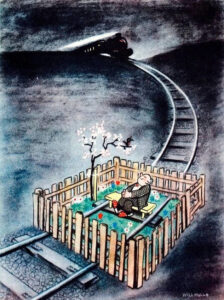

I was hoping that the treaty would be extended so that nuclear weapons could be converted for peaceful civilian applications. That the swords be beaten into ploughshares.

Unfortunately both camps were suspicious of the others’ intent.

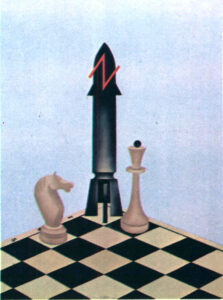

Nuclear disarmament would hinge upon the nuclear adversaries, suspicious of the others’ intent, being able to carrying out checks on each other.

Even if Home had pushed for such a conversion, he would have been swimming against the tide. Powerful men in both capitalist-particularly the American- and Communist camps, poised as superpowers unprecedented in world history, believed that nuclear war was inevitable.

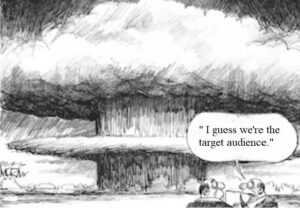

Stretching and flexing, each had the capability to do massive devastation or even totally annihilate the other, with the power to wield such forces and to do so quickly in the hands of a few leaders. The only question was who would push the button and strike first .

This question was the item of discussion when he and Harold Macmillan met with Kennedy and Rusk in 1962.

‘Your people, the British people, ’I reminded him, ‘are told they shall receive four minutes’ warning of any impending nuclear attack.

That’s not a very long time even though there are some people in that great country of yours who can run a mile in four minutes.’

I encouraged Home not to hesitate to use another button, the one on speed dial, to continue his country’s role as ‘honest broker’-what some cynics called the ‘Brutish Umpire’- between the US and the USSR. He thanked me for this

With nothing to lose he could seek to tone down the rhetoric, to reduce the decibel level on the part of the superpowers, reduce the risks without upsetting the balance of power.

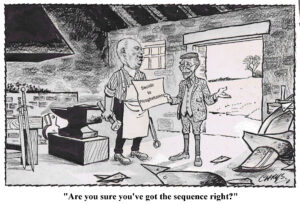

In encouraging him to take an independent stance for Great Britain in his preparation for reprising his role as Foreign Secretary, I made reference to wooden matchsticks. Douglas Home had said in an interview that he liked to use a box of matches to help him in his economic calculations. I put it to him that the matchsticks could be arranged in two piles to represent nuclear warheads of both the Soviet bloc and those of the NATO. I pointed out that unlike in a game when one side needs only more points to win the contest, in a nuclear face-off, one more warhead didn’t ensure victory.

Simple calculations would bear out what he obviously knew – that both had the capacity to wipe each other out many times over.

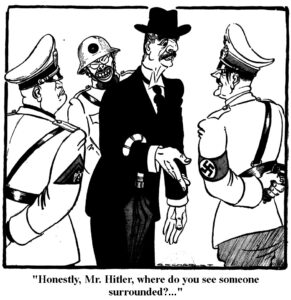

A letter of last resort is one sent to British nuclear naval vessels in case of nuclear attack setting out how to respond. My letter was one of first resort, urging disarmament so that that the others never have to be sent. I encouraged Home to look at the moves and counter moves of the Kremlin in a long perspective and to consider the nature of its ambitions as being very different to those of Nazi Germany. We had to look at its intentions rather just it’s capabilities. I didn’t believe the Soviet Union would take the first step in launching a nuclear shootout.

It had too much to lose and nothing to gain. Things were more likely to come to a head with its Chinese Communist rival than with the West.

The Soviet involvement in the Missile Crisis was a reluctant one. This view would be confirmed years later by its agonizing over military intervention in Afghanistan. It’s behaviour was cautious, defensive and fatalistic, whereas Hitler’s push for a military conquest of the world had had its logic in Germany’s need to catch up once and for all in the great race for empire building.

Douglas Home had witnessed first-hand Hitler’s subterfuge during the Munich negotiations.

He accompanied Neville Chamberlain there as his personal secretary.

Made against Home’s advice, Chamberlain’s comment on their return that ‘there will be peace in our times’ was one of the most indelible moments of the century. Though Home was not tainted by the fallout, the failure to stave off World War II would be cited by militarists in their infinite wisdom to provide justification for a pre-emptive strike on any totalitarian state in disfavour, such as the USSR or better still, a weaker one such as Iraq post Gulf War.

As Iraq went up like the fourth of July, the long, slow slide from The Asian Butcher’s yard into barbarism would quicken.