At UNE I attended classes given by Isabel McBryde, lecturer in Prehistory and Ancient History.

While developing courses and providing the first formal training of students in archaeology in Australia,

this trowelblazer was conducting a pioneering regional study of the New England region of New South Wales based on Australian archaeological fieldwork.

Isabel’s research was being focused on her studies of stone tools.

She concentrated on their distribution through trade and exchange.

Her activities involved stone sourcing, experimental tool manufacture and use,

faunal analysis, the careful and rigorous consideration of linguistics, ethnographic and archival records. She researched how fire was harnessed for land management and various purposes.

At the beginning she stated her professional mission statement: ‘We have to understand the past as a human reality.

‘It helps us understand who and what we are.’

One of the most inspiring things about Isabel’s research was its social nature. She was interested in a holistic, peopled past combining archaeological and ethnographic research in a manner that no-one before her had done.

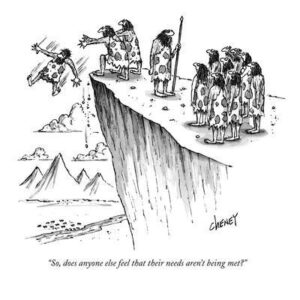

There was opposition to her work at the get-go. They said, ‘There’s nothing for you there, you should be in Athens or Egypt.’

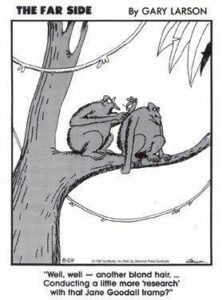

It was coming from the same male dominated academically restrictive mindset that discouraged Jane Goodall from becoming a professional primatologist.

There wasn’t much interest in things aboriginal. The prevailing view at this time was that everything was all finished, that contemporary aboriginals knew nothing. Why waste time and resources on ‘stones and bones’.

She put to us the conventional view of her area of knowledge: ‘The majority of the public view archaeology as being something only available to a narrow demographic, wouldn’t you agree?’

‘You took the words out of my mouth,’ I said. ‘It’s done mostly by upper class, scholarly men like Max Mallowan and Mortimer Wheeler attempting to uncover spectacular artefacts and features, or to explore vast and mysterious abandoned cities. ’

‘The job of archaeologist is depicted as a ‘romantic adventurist occupation’. To generalize, the public views archaeology as a fantasized hobby more than a job in the scientific community. The audience may not take away scientific methods from popular cinema but they do form a notion of who archaeologists are, why they do what they do, and how relationships to the past are constituted. The modern depiction of archaeology is sensationalized so much that it has incorrectly formed the public’s perception of what archaeology is. The public is often under the impression that all archaeology takes place in a distant and foreign land, only to collect monetarily or spiritually priceless artefacts.

Much thorough and productive research has indeed been conducted in dramatic locales such as Mohenjo-Daro and Ur, but the bulk of activities and finds of modern archaeology are not so sensational. Archaeological adventure stories tend to ignore the painstaking work involved.’

The Sacred Sites Survey she directed was about finding and connecting things. It was about bringing Aboriginal people into contact with their own culture and ones that have gone through similar development.

It was about a much more holistic understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal culture.

‘They enjoyed making music a great deal, didn’t they?’ I said.

‘It was and is central to the lives of everyone.’

‘Where did those before industrialisation get their instruments?’ I asked.

‘In constructing their instruments, Aboriginal Australians, like others in pre-industrial societies, used the resources at hand.

Where did those before industrialisation get their instruments?’ I asked.

‘In constructing their instruments, Aboriginal Australians, like others in preindustrial societies, used the resources at hand.

‘What musical groups do the instruments we retrieve from such societies?’

‘Most of their instruments fall into the idiophone class, where instruments consist of two separate parts which are stuck together to give a percussive sound. Throughout Australia, this kind of instrument takes many different forms. Of the membranophones, or skinned drum types, there is only one example. There are no chordophones, or string instruments; however in the aerophone, or wind instrument class, one example provides an outstanding exhibition of musical ingenuity.

In pursuance of her mission she and volunteer students drove four-wheel land rovers round across the bush on survey missions excavating and looking for sites. They could be found there knapping on the job. Mapping out those sites of likely significance, pondering the connection between ceremonial sites, stone circles, inscribed trees, and stone resources, and rock art sites all of which had to be carefully dated.’

Her documented findings were bringing aspects of the Australian past alive to a contemporary audience.

Our class got them first hand.

‘Archaeology combines many fields, doesn’t it, Ms. Mcbryde?’ I asked, employing this revived honorific as Isabel was still working on her doctorate.

‘In broad scope, archaeology relies on cross-disciplinary research. It draws upon many subjects.

For example a physicist can measure for us the efficiency of a bow drill, the prehistoric form of drilling tool, which was used to produce fire.’

‘Does it draw upon palaeontology, the work being done by Louis and Mary Leakey?’

‘It most certainly does, although as a field it is distinct from the study of fossil remains.

In my research petrologists are important colleagues.’

‘Because of their faults, not in spite of them, I trust.’

‘Sedimentary, My dear Watson.’

‘And other geologists?’

‘They help us understand such formations as quicksand that we come across where creeks and rivers flow into the sea and along riverbanks.’

‘Have any of your team ever been swallowed up by it?’ I asked jocularly.

‘Fortunately that only happens in old Hollywood movies.’

In her approaches to teaching and her wide research at New England Isabel stressed the importance of a regionally focused archaeology.

‘Through detailed field surveys and site recordings we aim to provide significant context for the investigation of key sites by careful excavation.’

I asked, ‘Considering you must be working on a tight budget, how do you explain the success you achieve?’

‘We use a lot of local people – field naturalists, historical societies, local groups and aboriginals. We’re committed to developing strong, mutually beneficial relationships with Aboriginal communities.’

‘This is the first time that I’ve ever met and talked to Aboriginal people,’ one of her volunteers told me. This was a different world to now. People at that time were very unfamiliar with aboriginal culture and aboriginal people.

Isabel said, ‘It’s imperative to talk to Aboriginal people about sites. This contact is based on recognition of their concerns about the places holding significance for them. As with other native peoples, natural features such as lakes, mountains or even individual trees have cultural significance. We respect and welcome the sharing of traditional knowledge about such places, and how they should be treated. Within these interests we are developing and promoting approaches to research based not only on prior consultation with indigenous people and other stakeholders, but on their active collaboration and involvement in the research. We are extending our network of informants.’

‘What exactly are you looking for at these sites sites of the cultural landscape?’ I asked.

‘What we’re really looking for are the remnants of the ‘pristine’ ‘untouched’ ‘uncontaminated’ culture, that was here before 1788.’

‘The pure Aboriginal culture prior to European invasion,’ I said.

‘Yes, what we see as the ‘good stuff’ – the sacred sites, the totemic places, the last initiation places, all of those places.’

‘Where does this view arise from?’

‘It arises very much from the whole eighteenth-century view of the noble savage and the idea that if you could just look at aboriginal society as it was, you will find out something about the development of human society.’

‘What are your main concerns, Ms. McBryde?’

‘What we are really worried about is not so much encroaching development, but the activities of curbstone collectors who are, to some extent, going around exploiting sites and trading in stone artefacts and such things. We’re worried about remnants that are being destroyed not so much deliberately or looted, but through the ignorance of the non-Aboriginal people of what might be a sacred site.

We’re really worried by the long term dislocation of communities, the movements of people, children being taken from their families which all take their toll. And of course we may run into some strong headwind over excavation of human remains.

Our immediate job is to make sure that we archaeologists get permits to excavate. There’s a wealth of information out there that needs to be obtained.’

‘What is the official response to your line of investigation?’ I asked.

‘There’s a lack of interest. The powers that be say that they believe there is very little left in New South Wales – that really there isn’t anything to find. They think that basically there’s no connection between aboriginal people living in New South Wales and aboriginal sites.’

‘That’s a difficult baseline for you,’ I commented.

‘So we have the big problem of people saying, ‘Well, we’re not going to waste money on New South Wales’. Settled Australia is considered not to be really relevant. ‘What do you see as most relevant, Ms. McBryde?’

‘We on the other hand stress the importance of people’s historic memories wherever.’

‘What qualities do you look for in those key individuals in the aboriginal community who take part in forging these connections?’

‘We need those who have the requisite connections with the community and who also have the requisite know-how to be able to work with the sites. We encourage those taking part to go to the reserves and put out feelers as to where the old people are. This can help gain an entrée into the community.

‘What places are of most value to aboriginal people?’

‘Any places that have evidence of Aboriginal occupation, that is basically archaeological sites, have a contemporary value to Aboriginal people. They must be consulted.

Their family and kin obligations have to be understood and respected.

No sites should be excavated or damaged without Aboriginal agreement or discussion. They must be conserved.

‘What is the effect of this involvement on aboriginal people?’

‘When aboriginal people are asked to be involved, they feel a sense of importance. A heightened understanding of their heritage leads to a greater sense of cultural identity. Often for the first time in their lives they can get some recognition. This way we reconcile archaeological and Aboriginal interests.’

‘It sounds like every prehistoric hunter’s dream. Killing two birds with the one stone’

This was the period of assimilation, you must remember. For a long while aboriginal people had been encouraged, even by progressive aboriginal people, to forget their heritage.

‘So by locating, recording and protecting the physical places, the sites and stories of Aboriginal culture, this can help lead to a cultural ‘renaissance. Do you lend any credence to this idea?’

‘What this survey does is to fill in pieces of the Dreamtime jigsaw. The elders can help us interpret our finds and see the whole picture. It can help lead Aboriginal communities to cultural revival.’

‘Haven’t aboriginal communities been thoroughly researched over the years?’

‘They’ve had researchers before. The ‘oncers’ who just came once and asked about their culture and knowledge but gave nothing back in return. Nothing went back to the community. So they were reluctant to give information. They’ve never actually had anybody previously making really practical, on-the-ground efforts aimed at producing site reports, specifically talking about landscape and also rules, initiations and so on.’

‘So you have to win the people’s trust.’

‘Our survey team’s view is if we get something, we’ve got to give something back.’

These communities have their conservatives just as we do. They can say, ‘No, you can’t go there. You can’t do this’. Those people possibly have a grudge and don’t want to work with a white person. There’s always a certain amount of suspicion and caution and conservatism towards the work that we are doing that’s expressed most typically in something like, ‘No, these places should be kept secret’.

Then there are the very open-hearted, open-minded who really enjoy taking us to these places, and speak with a great deal of pride about these places, that are so special to them. I’m talking about some of the very proud old men and women. They are the experts and they tell their story. These elders are relieved that the story of their people is being recorded, to be passed back to the communities and to the children, the next generation. They want all to appreciate their culture.’

‘And the younger people?’

‘The younger people, who have a little bit of knowledge, know where we are coming from. They have a bit of their own knowledge but not much, and they are much thirstier for knowledge.’

‘Knowledge about what kind of things specifically?’

‘We want to get everything that people are be good enough to tell us, and we want it documented. Our focus of interest varies between magnificent mountains, strips of coastline or islands or whatever, right the way down to small rocks. To single graves and to a scarred tree that may or may not have been a canoe tree.’

What do you do when people don’t want to deal with you?’

‘Our view is – well we know it’s there, they don’t want to talk to us, but just as constant dropping wears away a stone, we’ll persist in gaining their trust.’

‘We press for signs to be made up saying ‘Sacred sites’, ‘Aboriginal burial’ and ‘Aboriginal sites protected under the Act’. These signs are very visual and the elders can say, ‘Well there, if anyone destroys this, they can get prosecuted. – there is an Act to prosecute’. They saw something positive with us. They see we conserve their heritage and their culture. The reports we write up can be taken back to communities saying, ‘Is this right? Does it need to be changed?’

If we target a community and we knew the information is there, we’ll go back and back. They might say, ‘Oh no, we’ve got no sites’, ‘No, we don’t know nothing’. So we’ll come back and we’ll and say, ‘What about your old mission cemetery?’

‘Oh yeah, they’re important, yeah.’ Once we start working with a community to protect some of the sites, it might be one of the old mission cemeteries, then they might open up and say , ‘Oh we’ve got this other site here’, and it might be a story site about a hill or a mountain, a river, a creek. They start slowly, not giving too much information out, but small, slight wrinkles. Then we’ll go to another community and build the relationships up with the tribal groups and communities elsewhere. It’s a slow process but it’s the only way.’

Dr. McBryde is today recognised as one of the founders of archaeology in this country. In the process she won the affection and respect of Aboriginal people. Isabel’s pioneering approach to community archaeology would lead to her involvement with the famous find of Mungo Lady, the earliest known anatomically modern human inhabitant of Australia, and the negotiation of the return of her remains.

The cremated bones were returned and there was extensive negotiation about the management of and compensation for the World Heritage site. Isabel’s quiet, but insistent and continuous negotiation through her personal, moral and humane understanding of Aboriginal people and their culture was successful. Her empathy with those strong Aboriginal women was so different to the rivalry and ego-driven views that still underlies so much academic research.

Isabel would be largely responsible for the shift of research into the archaeology of Aboriginal Australia from the museum to the university sector.

The tests she set were very rigorous but I managed to scrape through.

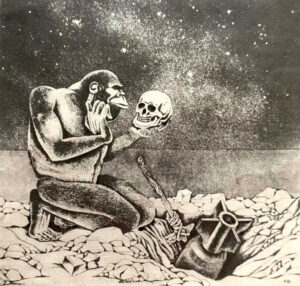

Out of Africa.

Taking time out from digging Louis Leakey wrote to me on Christmas Day 1968 to wish me a joyous holiday season and to clue me in of developments in his life and work. He had had an operation on his hip and was getting around walking on two sticks.

The Leakey family of archaeologists, anthropologists and palaeontologists made many contributions to the study of the origins and ascent of man.

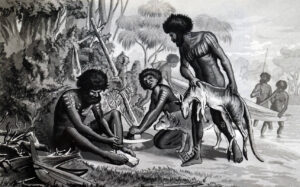

Louis and his wife Mary, who had attended Mortimer Wheeler’s lectures at London University, conducted excavations at various fossil sites in East Africa. From 1931 to 1959 they worked at Olduvai Gorge reconstructing a long sequence of Stone Age cultures dating from approximately two million to 100,000 years ago. They documented the early history of stone technology from simple stone – chopping tools and flakes to relatively sophisticated multipurpose hand axes. Louis experimented with techniques of knapping stone tools and attempted to understand how prehistoric hunter-gathers gained their food.

In 1959 the Leakeys discovered the skull of Australopithecus boisei, a species of the pre-human genus Australopithecus.

Dubbed “Nutcracker Man” because of its huge molars, indicative of a vegetarian diet, It was dated at about 1. 75 million years of age.

. They also discovered at a deeper level some pre-human remains representing an older less robust species – ‘Homo habilis’.

‘Handy Man’ is possibly ancestral to modern humans.

Both new fossils were associated with stone chopping tools. Soon they would fall upon the Homo erectus cranium that is about a million years ago.

Dr. Leakey’s fossil discoveries proved mankind’s roots were African, not Asian, as had previously been supposed.

They revealed how relatively short early men and women were, a fact people today can find so surprising.

He told me of an exciting discovery he made – a lump of lava which was used by Kenyapithecus wickerei.

This ‘very early ancestor of man himself’ used it to break open bones in Upper Miocene times.

It was associated with bones exhibiting depressed fractures and some skulls broken open to obtain access to the brain. These discoveries date back to about ten or twelve million years ago.

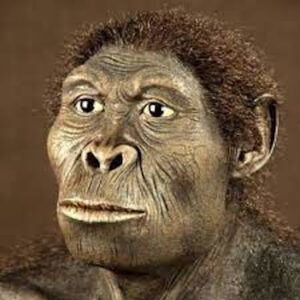

Louis, the son of English missionaries, was a pioneer into the study of primates – the highest order of mammals – including man, monkeys and apes. Louis Leakey’s interest in primate ethology stemmed from his attempts to recreate the environment in which Proconsul, an extinct primate ancestor who lived in the Rusinga Island region of Lake Victoria. He saw similarities between this environment and the habitat of the chimpanzees and gorillas. He believed that these studies would increase understanding of embryonic humans. After unsuccessfully trying to find an observer, Leakey was considering taking the job himself when Jane Goodall brought herself to his attention.

What was about this young English woman that proved so providential for Dr. Leakey? I tried to visualise ‘Jungle Jane’, this hazel eyed white woman living rough in the jungle, and rate her alongside some of the fictional heroines I was familiar with. As a child I had followed the adventures of a whole string of young romantic heroines in deepest, darkest Africa, ‘The Multimates’ you could call them, who’d swing into the hearts and minds of beardless boys like me, coming back monthly for another issue. They caught my imagination just as Tarzan had caught that of young Jane Goodall.

This raised certain questions. Did Jane fit into the Jungle Girl mould because of her background, character, costume and the content of her stories? How did she measure up to the Multimates? Was she a feminist icon or would she end up a scantily clad damsel in distress? Who and what did she confront? With which native companion?

Was she brought up in Africa or had her missionary parents brought her? Was she like Taanda, The White Princess of the Jungle, raised from a crawling, helpless she-cub and schooled in the ways of the wild? Or was she like her namesake, the American Jane who went on to become Rulah. Jane was a bored American girl with no home, no family, just money and a yen for adventure. While flying solo one day, she crashed into the African jungle. This of course tore her clothes to shreds . ‘Tsk, tsk! I’m like Eve in the Garden! What’ll I do for clothes?’

Fortunately for this Jane her plane beaned a giraffe on the way down – it’s lying dead in the next panel with its tongue hanging out- so Jane wisely skinned it to make a bikini. She saved a native tribe from the trickery of an evil white villainess named Nurla, and the natives were very grateful. ‘We acclaim you! You rule us!’ But first she had to prove herself in combat, so the natives unleashed a starving leopard on her. ‘One must die. You or hungry cat’.

Jane got slashed up pretty badly with lacerations on her arms and legs and blood drops spilling out, but eventually killed the cat with her knife. Having proven herself, the natives name her Rulah the Jungle Goddess: ‘We will serve you forever!’ and Jane decided to stay because she liked the attention: ‘A Goddess, eh?… I like it!’.

Was Jane Goodall like Princess Pantha, a former circus animal trainer and Ju-jitsu expert as well?

Did her name disqualify her? Most jungle girls had exotic names like Sheena, Cave Girl and Nyoka,

But then there was just plain Ann and Jann. And that fictional namesake Jane renamed Rulah. Not to forget of course Tarzan’s jungle companion Jane.

For the Jungle Girl her garb was a matter of great importance. A Jungle Girl just never knew when she was going to get captured and tied up. Normal jungle girls like Sheena wore the smallest fur and leopard skins and spoke broken English.

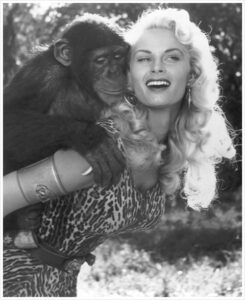

Our Jane was like Nyoka, civilized, dressed in safari gear and interested in studying apes.

Like Sheena, our Jane was blonde.

Was she a strong character like Sheena, Nyoka, ‘Cave girl’ and Rulah?

With her ape companion named Chim, Sheena was always rescuing her useless male companion from whomever had caught and tied him up that month. The villains ranged from slave traders to Nazis. She was a very tough heroine able to take on crocodiles, gorillas, lions and natives. Her knife was her weapon of choice and she was known for corny one-liners in broken English like ‘My knife is swifter than your claws, killer‘. Sheena was conceived as a female version of Tarzan, with overtones of H. Rider Haggard’s ‘She Who Must Be Obeyed’.

Rulah was a heroine in most issues and was the dominant character. One of the biggest differences between Sheena and Rulah was that Rulah relied more on dumb luck than actual skill to survive.

In most of her stories Nyoka is knocked out and tied up at least once. She is also usually the rescuer of her almost useless fiancé, Larry.

‘Cave girl’went skinny dipping got beaten, whipped, tied up, trapped in a net and of course saved the day. She had a monkey as a pet named Nikki who responded to everything with ‘cheeka-cheeka’.

Not to forget Jungle Jann who was always fighting the same hunters and poachers.

Unlike Ann, Jungle Jane obviously didn’t fit the classic damsel in distress stereotype. If it were not for her male companion Kaanga, Ann would have been a slave, killed by wild animals or the main course of savages a hundred times over. She was tied up in every issue and tied up on the cover of almost every Jungle Comic. Her character did little other than find herself in precarious situations.

So how did Jane Goodall size up to the Multimates’? This intrepid female, who lived in the jungle, never fought wild lions barehanded, wrestled with giant pythons or saved native tribes but called out the worst kind of poachers and hunters. And in her favour, she added immensely to our knowledge of nature. Her discoveries were one of the great achievements of 20th-century scholarship. It worked for me! Jane stole our hearts in the early 1960’s as National Geographic’s star of the forest, fighting entrenched ideas about primates, wrestling with basic ideas about the species, recruiting people around the world to help prolong life on our planet. It amazed and delighted me that a person could sit so calmly with these magnificent, wild creatures.

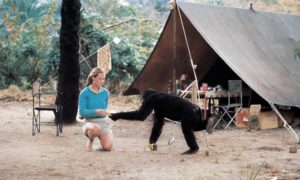

She started working with Louis and Mary digging up fossils in the Olduvai Gorge. Dr. Leakey was taken with Jane’s briskness, general knowledge and avid interest in animals.

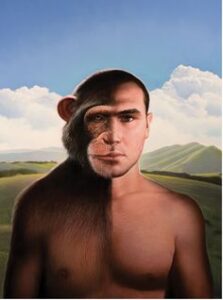

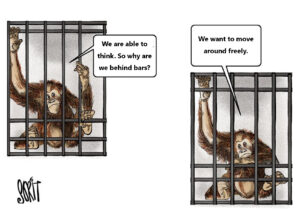

He hired her as an assistant and eventually asked Jane to undertake a study of a group of wild chimpanzees living on the lake shore in Tanzania. Previous studies of primates had been confined to captive animals but Leakey believed, presciently, that much more could be learned by studying them in the wild. He reasoned that knowledge about free living chimpanzees, who were little-understood at the time, could help scientists answer some questions about our evolutionary past.

He believed an understanding of chimps in the wild could lead us to understand how our ancestors may have behaved. He wanted to find evidence of shared ancestry between humans and the great apes.

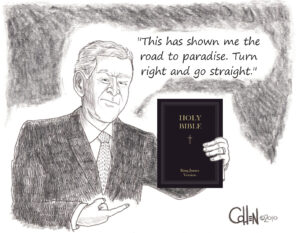

I had first become interested in this question after watching ‘Elmer Gantry’ played by Burt Lancaster. Gantry, a confidence man selling fundamentalist religion to small-town America, shares the stage with a chimpanzee to decry and dispel the “idea” of evolution.

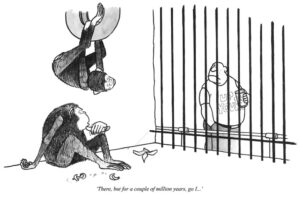

Jane Goodall based her work examining the relationship of humans and chimpanzees on the idea of evolution . One day in 1960 she was walking through a rainforest reserve at Gombe, in Tanzania, when she came across a dark figure hunched over a termite nest. A large male chimpanzee was foraging for food. So she stopped and watched the animal through her binoculars as he carefully took a twig, bent it, stripped it of its leaves, and finally stuck it into the nest. Then he began to spoon termites into his mouth.

Thus Jane made one of the most important scientific observations of modern times in that remote African rainforest. She witnessed a creature, other than a human, in the act not just of using a tool but of fashioning one. ‘It was hard for me to believe, ’ she recalls. ‘At that time, it was thought that humans, and only humans, used and made tools. I had been told from school onwards that the best definition of a human being was man the tool-maker – yet I had just watched a chimp tool-maker in action. I remember that day as vividly as if it was yesterday. ’

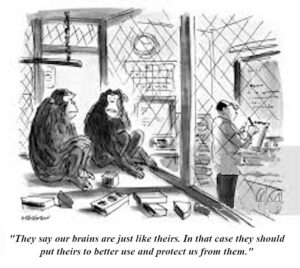

Up until that point, anthropologists saw tool-making as a defining trait of mankind but here was evidence to the contrary! When Jane Goodall telegraphed Louis Leakey with the news of her discovery, his response has since become the stuff of scientific legend: he wrote: “Now we must redefine ‘tool, redefine ‘man’ or accept chimpanzees as humans.” Dr. Leakey was exaggerating but not by much. He was was ecstatic. The distinction between man and ape was blurring.

Also in her first year at Gombe,

Jane observed chimps hunting and eating bush pigs and other small animals. This was an important discovery because scientists thought that chimpanzees were primarily vegetarians.

Jane’s subsequent observations found that not only did Pan troglodytes – the chimpanzee – make and use tools but that our nearest evolutionary cousins embraced, hugged, and kissed each other. They experienced adolescence and developed powerful mother-and-child bonds.

They used political chicanery to get what they wanted.

.Through the decades, Jane and fellow researchers continued to look at chimpanzee feeding behaviour, ecology, infant development, aggression, as well as other primate species. They also were able to document details of chimpanzee “consortships” — periods in which males take females away from other community males for unchallenged mating time. Jane suggests that chimpanzees thus show a latent capacity to develop more permanent bonds similar to monogamy or serial monogamy.

Chimpanzees are well known for being loud, noisy animals. Film depictions of chimpanzees usually show them whimpering, hooting, screaming and generally making a ruckus . However, chimpanzees are also well known for being intelligent, and by using field experiments and naturalistic observations we have found new evidence that chimpanzees know when to keep quiet. Such as during a simulated intrusion by a foreign male.

It also became clear that chimpanzees had a dark side just like human beings. They also made war, wiping out members of their own species with almost genocidal brutality on one occasion that was observed by Jane. They may be capable of cruelty but they also demonstrate cooperation, affection, happiness, sometimes even seem to help each other just for the sake of helping, not to get a reward.

This work has held up a mirror, albeit a blurred one, to our own species, suggesting that a great many of our behaviours, once thought to be uniquely human, may have been inherited from the common ancestors that Homo sapiens shared with chimpanzees six million years ago before both lineages went their separate ways. There is no “missing link” between apes and us. Chimpanzees (or other apes) didn’t evolve into humans. No matter what some postulate there is no missing link there.

.At the same time the researchers were alarmed to realize how widespread and urgent were the threats facing wild chimps.

The message was clear: We understand chimps much better now. They are more like us than we ever imagined. But now we must help save them.

Louis told me of her continuing success and that of Dian Fossey. Jane and Dian were the first of The Trimates, sometimes called Leakey’s Angels, the name given to three women sent by Louis to study primates in their natural environments.

They studied chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans.

In the eyes of Louis, the Trimates had two important virtues. For one none of them had too much specialised training, minds uncluttered and unbiased with theory. The second was their gender. He thought women were better than men when it came to studying wild primates. The payoff came from the women’s capacity to empathise with their subjects, seeing them as individuals whose life histories influenced the structure of the group. It would take time for the significance of the individual personality in primate groups to be recognised.

Jane began her first field study of chimpanzee culture in the Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania. Before Jane, naturalists rarely came into close contact with the animals they wrote about in their scientific reports. Before Jane they were astir even if all they saw was an arm or backside disappearing into the bush. To sit with animals as she did without them running away was unthinkable.

She had to contend with male chauvinist academics who tied up her progress with their hidebound thinking. She had no academic training, having grown up in the middle-class gentility of Bournemouth in the post-war years, a time when women were expected to be wives and little else. Other male primatologists were quick to dismiss the results derived her way as untutored female sentimentality. They pulled Jane’s predilection for giving the chimpanzees names to bits; it would have been more scientific to give them numbers, they said. Jane had to defend an idea that might seem obvious to laymen – that chimpanzees have emotions, minds and personalities.

At this time scientists were particularly sensitive about giving human attributes to animals. Anthropomorphism was simply not on, they told Goodall when, in the early 60s, she took a PhD at Cambridge at the insistence of Leakey – who was desperate for his protégé to gain academic respectability. ‘These people were trying to make ethology a hard science,’ Dr. Goodall recalls. ‘So they objected – quite unpleasantly – to me naming my subjects and for suggesting that they had personalities, minds and feelings. I didn’t care. I didn’t want to become a professor or get tenure or teach or anything. All I wanted to do was get a degree because Louis Leakey said I needed one, which was right, and once I succeeded, I could get back to the field.’

As for me I would take Louis Leakey up on his encouraging me to increase education and public understanding of human origins, evolution, behaviour, and survival.

I decided to study chimpanzees not in the field but in their captive habitat.

I saw myself as possessing the qualities Dr. Leakey saw as essential: someone with an open mind, with a passion for knowledge, with a love of animals and great patience.

Along with the other expeditions into space I had followed the flight of Ham the astrochimp, with great interest.

I became interested in anthropomorphism, the attribution of human characteristics or behaviour to an animal.

I also became interested in it’s reverse, zoomorphism, how chimpanzee attributes in particular are assigned to humans .

So much so that I could imagine some hybrid hominids swinging from the trees.

I have long wondered whether one day chimpanzees could evolve to attain the powers of speech that enable us humans to perform highly complex functions.

The stumbling block is their lack of neural control over their vocal tract muscles to properly configure them for speech.

Chimps at Taronga.

With a magnificent panorama of the city skyline and the construction site of the Sydney Opera House, the ferry ride was a treat on its own. Once I docked, there was a five minute hike up to the zoo entrance.

I was dropping in on our closest relatives. I wanted to learn about what the chimpanzees were really doing. My mission was to get close to them, for them to get used to me and for us to communicate with each other.

I got closer physically than Jane Goodall had initially in her contact. The metal bars helped of course. They didn’t run away from them which was a good omen. It meant I could study the details of their behaviour.

I was there soon after a big event in the late sixties was being celebrated. A little bundle of joy had arrived. The story arose that the stork had come from a nearby aviary to make a special delivery. Some people have all the luck. Mine was to observe the new-born chimpanzee. A miniature version of its mom, with fluffy black hair covering most of it’s body plus a a little white tuft on it’s rump, it was being carried out into the open compound by mama whilst cradled in her arms. Once seated, she started grooming it and vocalizing soothingly, calming and reassuring the little one.

‘Is it a boy or girl?’ I asked a keeper.

‘It’s a male. We were able to identify the sex of the healthy new chimp within a matter of hours. after an eight-month pregnancy and a smooth birth, Mother Bessie was so proud to show off her new arrival. As you can see, she has shown her great experience since the birth, confidently carrying her youngster out into the the open. Her first baby had to be taken from her and bottle fed but now after having given birth to more babies, she’s relaxed, certain and easeful with her role,’ he said.

‘How’s he doing?’

‘The little baby boy is doing really well spending his time feeding and sleeping. At four pounds, he’s very healthy and very alert and it’s really great to have the latest member of the new generation on the ground. For a three-day-old baby he’s aware of what’s going on around him and this doesn’t usually happen until they’re a few weeks old.’

‘What kind of things do you have to watch for?

‘We watch for chimps to reach milestones similar to those of human babies. There shouldn’t be any problems with him reaching them. In no time he’ll be holding his head up on his own and beginning to teethe. He’ll be learning vocalizations and facial expressions. He’ll be using his long fingers and toes to grasp, hold on and walk properly.’

‘How long will he stay with his mother?’

‘For at least four years she will nurse and care for her offspring before cycling into estrus again. For the first several months of life, the little one will be pressed constantly to its mother’s body. He will cling to her and she will carry him around, never putting him down, only gradually allow her offspring to venture away.’

‘Do the mothers ever not accept their babies?’

Maternal rejection is not uncommon in captive chimpanzee populations. In those cases we need to hand rear them.’

‘What effect has this one’s arrival had on the chimp community?’

‘The arrival of any new chimpanzee has a profound effect on the social structure of the primate community. The newborns are very important for the stability of a community of chimpanzees. Everybody loves kids and infants are good for reconciling and dissolving tension between all the members of the community,’ he said. ‘With this new generation of chimps coming through, we’re seeing a lot of altruistic behaviour to the new arrival from other chimps. From the first moment they laid eyes on the little one, our chimps have been keenly interested in him. They’ll soon be playing with him, and mentoring him as well which will be very nice to see. We know from experience that safe social interactions with each member of the chimp troop will be key to his eventual introduction. ’

‘Was Bessie born here too?’ I asked.

‘Bessie is in her mid teens. Like most chimps back then, Bessie, Bess Bess, Bessie Ann, Princess and all the other names she’s been affectionally given was wild when she came. Many chimps in zoos were captured from the jungles of Africa at a young age. It’s a sure bet that they were traumatized, brutally ripped by poachers from the arms of murdered mothers.’

‘How has this activity affected the species?’

‘It has endangered it. It almost always means chimpanzee death – for the mother who won’t give up her baby, and for the males who try desperately to protect the females and infants from the hunters. As you can see, mother chimpanzees are very protective of their young, just like human mothers, and would never allow their babies to be taken from them.

Zoos are more aware today of where their animals come from and so are taking fewer baby chimps from the wild.’

Another female, a juvenile, her hind legs slightly flexed, body inclined forward, the backs of her fingers placed on the ground, approached Bessie and sat next to her. She was tiny. Big ears framed a light-brown face, and her wide, honey-colored eyes made her seem perpetually surprised. She swatted the flies away from Bessie while trying to get a closer look at the newcomer.

‘Let me introduce Lulu.’ said the keeper. She goes by many names: Lulu, Lulu bell, Sweetheart, Darling. The list goes on. She has led a fascinating and globetrotting life so far. After being caught in the wild, she was initially hand-raised in a family home in Florida USA, but when she was unable to stay there she was moved to a roadside circus. She performed on a bike wearing a tutu that she could dress herself in.

After that she was transferred to St Louis Zoo.’

Lulu came over to the side of the cage and stretched out her arms. Then holding her hands together, she pulled them towards and away from her repeatedly. The keeper then pulled a toy rake out of his bag and gave it to Lulu . She set about sweeping a pile of sawdust and wood shavings on the concrete floor.

‘What we do know is that she arrived at Taronga in early 1965. Like all chimps, she has her own distinct personality and characteristics. As you can see, she likes to keep on earning her keep. There are tales of her finding scrubbing brushes in the exhibit and using them to scrub the walls. She’s super smart. This was first spotted shortly after she arrived at Taronga. One of the gardeners had left a rake inside the enclosure. Lulu decided to finish the job and raked up leaves.

Because of her background, Lulu had to learn to be less of a human and more of a chimp. She continues to display human characteristics, such as walking on two feet and eating daintily.

‘Aba, daba, daba, daba, daba, daba, dab, it’s bedtime for Bonzo,’ I said to the alpha male chimpanzee lying on top of a rick of hay yawning repeatedly and grunting softly.

‘Bonzo’ as I called him was in a sterile steel cage with access to the outdoor compound. I had a a good view of the cage and I could even get up close to feed him. The big musky smelling chimp came out of his lethargy as though some thought had awakened in his brain. As I approached, he tracked my movement. He got up, stamped up and down the cage and finally peered through the cage at me with bristling curiosity. Looking into his flat freckled face, at his big, bare ears and pronounced brow ridge, I could see the extraordinary similarity with some of the Alpha males back in Wright College.

And what was it with chimpanzees and that middle parting, I thought? Stuck in the Twenties, aren’t they? I gave this one a handful of nuts mindful that that was what Dr. Goodall had fed them. He gave a series of grunts which I took as a sign of gratitude.

When the keeper came towards him and bent down, Bonzo took off his hat and posed in it. Just like a baby he put his arm around him and hugged him, chattering all the time. I could see the very real bond between human and animal. The keeper had brought him a tin mug of water which Bonzo employed his opposable thumb to hold and empty in one gulp.

Another male knuckle walker who had been heading the morning patrol around the troop’s habitat charged up and got into a tug of war with Bonzo over who should hold the mug. His thick mottled hair bristling, he tipped his head, slapped his hands together, panted, standing upright on his short, slightly bowed hind legs, stomping his feet, and threw hay at Bonzo. He let out a full throated scream, his lips bunched in ferocious scowls. He made himself look as big and dangerous as he possibly could.

Bonzo responded by crouching, presenting his rump, holding his hand out. He accompanied this by pant-grunts, squeaks and then grins by baring his teeth. This was a nail-biting moment between a more dominant and a less dominant member of a group. The latter was the one who smiled leading to the aggressor becoming more friendly. Bonzo wasn’t showing off any weapons. He was making a sort of display of submission to the more dominant member.

‘His bark is usually worse than his bite, said the keeper. ‘It’s not the signal for the beginning of a fight. The alphas do this in order to show their aggressiveness without actually having to prove it in a fight. This way they stay boss for longer. Chimps communicate so much to each other through bodily gestures and postures. Physical contact is essential as it can relate emotions.

Ahead of his time as usual, Charles Darwin made a number of observations on the similarities between human smiling and laughter with facial displays found in chimpanzees.

Just looking at their display of facial expressions I too observed what seemed to be feelings in common with humans:

Excitement

|

|

Quizzicality

Thoughtfulness

Contentment

‘We call the teeth baring grimace the “Grin of Fear”, said the keeper.

It’s easy for newcomers to chimpanzee behaviour to misinterpret some of the expressions of chimps seemingly grinning happily. You can compare this ‘grin’ closely to a human’s tremulous smile when laughing at an awkward joke or feeling uncomfortable in a scrape.’

Just then Lulu put her arms around the guys which had an immediate visible effect calming them down. In response, the dominant individual made gestures of reassurance, touching, kissing and embracing the subordinate Bonzo. This reflected wisdom.

‘Older females such as Bessie and Fifi , ’said the keeper, ‘are the lynch pins of a successful community. Their maturity and life experience are often called upon by other members in order to alleviate altercations and facilitate reconciliation. It is the mutual respect shown by antagonists to these senior females that can prevent conflict. Females in our zoos take on a more active role than their sisters in the wild. Because of the restriction on their movement, the females can’t hide and end up directly confronting situations they wouldn’t have been party to in the wild. They keep more to themselves there. Females in zoos seem to be less fearful of males than those in the wild.’

‘How do the males respond to this assertiveness?’

‘To achieve longevity in the alpha male role, the smart alpha will form alliances and coalitions with the females and their offspring.

He does this by grooming the females and by allowing the infants of those females to play with him, to take food from him and generally to interact with him.

This scenario is often seen halting potential problems caused by squabbling infants. In other words individuals like Bessie have important roles in a healthy community. ’

‘Does Bessie ever get involved in fights herself?’

‘Bessie herself is an extremely amicable individual. Those of us that have known her for a long time cannot ever recall her starting a fight, or indeed committing any act with malicious intent. And that goes for Fifi and Lulu.’

‘With respect to conflict resolution, do chimps in captivity behave differently to those in the wild?’

‘In the wild it’s definitely a male-dominated society. Interestingly when a male comes into captivity you may have a female who’s been there longer and the male will tend to respect the females more, ’ he said. ‘Chimps in a captive situation are also better at resolving conflict quickly than in the wild because they have to be. ’

‘Do the fights between males ever lead to bloodshed?’ I asked the keeper, looking behind him to make sure he’d locked the padlock gate securely.

‘Back in the twenties, a chimp named Casey, following the natural instincts that chimpanzees exhibit in the wild, killed a Japanese macaque that was in the enclosure next to him. He tore down the bars between his cage and that of the Japanese ape, which he seized, trampled and strangled. He then smashed the body about until every bone in it was broken. Spectators said the rage of the chimpanzee was the worst exhibition of animal rage they had ever seen.

‘So they’re like humans in that respect.’

‘Recent research by Dr Jane Goodall has revealed that chimpanzees do hunt and kill other species in the wild.’

‘Why do you think Casey behaved like that? Is it because of some inherent streak or because of human interference?’

‘We can’t rule out the way in which the chimps were kept then. Little was known about the biology of chimpanzees then and what was needed to house them in a captive setting.

During the nineteen thirties serious welfare concerns were raised about the poor conditions the animals in the Taronga menagerie were being kept in. The chimpanzee enclosure was described in one newspaper as being small dark huts. This was not likely to sweeten the temper of unfortunate animals whose only outlook on life was through iron bars. This applies to all captive apes.’

‘Presumably even when you’re looking after them well here,’ I said, ‘they cannot experience the situations that their nomadic relatives experience. They can’t travel distances, or forage for their own food. They are eating without expending the energy normally needed to acquire food or shelter. I’ve heard when they get really bored, they will pace up and down or pull out their hair.’

‘It goes to show that just as with humans, if they’re forced into intolerable conditions, something can snap. They can explode into a rage or attempt to move forcibly somewhere else. That’s why we have to provide them with ideal conditions. Chimpanzees born and raised in reputable zoos and sanctuaries don’t differ much physically from those in the wild. The zoo diet, while less varied than the wild diet and occasional meats, has the benefit of consistency and can enhance a chimp’s growth. In addition, basic foraging skills seem to be either instinctive or learned without tears in captivity. Given adequate space and environmental enrichment here, they cover nearly as much ground and burn approximately as many calories as they would in the wild.’

‘And importantly here they can receive protection.’

‘‘Degradation of forests by human economic activity means that remaining habitat patches are often small and unconnected. Fewer trees, sinkholes left by mining and fences erected by ranchers can hinder movement and make it risky.

Loss of habitat or food can create ever greater competition for resources. It’s the same with us naked apes. I don’t think either chimps or humans are natural born killers but circumstances can push members of both species over the top.’

‘Just like Cain and Abel, ’I said.

‘Just like Cain and Abel, ’I said.

‘When some hominids go ape there is a terrible potential for destruction. The world is painfully reminded of this again and again.’

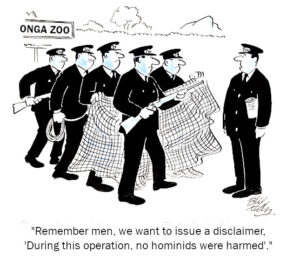

‘ Is it common for chimps to escape?’ I asked.

‘Contrary to what you would reasonably assume, most zoo animals are very reluctant to leave the security of their enclosures. At the same time it comes as no surprise that monkeys and apes are the zoo animals most frequently implicated in escapes. This is due to their dexterity and volatility and intelligence.

‘They can’t make fire, can they?’

No, but they have an understanding of it’s behaviour under varying conditions. This allows them to predict its movement, thus permitting activity in close proximity to the fire.

And remember chimps like ours are much stronger than a person. Though a chimp is a human’s closest genetic relative, it is nonetheless an animal we have never been able to fully tame. Even one hand-raised among humans with familiar, close and emotional bonds will, at some point in time, transform from a tame and predictable animal to a dangerous one. If loose in the zoo grounds, this necessitates either shepherding the public into ‘safe houses’ or the complete evacuation of the zoo. Luckily for the zoo’s Mosman neighbours, most zoo escapees rarely stray far from the home territory and security represented by their enclosures. ’

‘What have been the most memorable breakouts?’

‘Lulu once escaped from the original chimp exhibit she was in.

Her head keeper found her, took her hand and quietly walked her back into the exhibit.

More seriously, back in the mid-1950s Koko, another ex-circus chimp, escaped from her enclosure. After sprinting through a thankfully deserted zoo she leapt into the office manager’s little Ford Prefect car parked inside the grounds. Now chimps are smart animals. Koko herself had spent a lifetime in close contact with people before her increasing age made her unpredictable and dangerous, so opening and then closing behind her a car door presented no problem.’

‘Surely no chimp is quite smart enough to start a car and joy ride it through the zoo. ‘ I said.

‘That probably explains what happened next. Koko, at the end of her rope due to her lack of driving skills-or maybe she was a Holden girl at heart- decided to trash the Ford’s interior. One of the keepers present at this demolition told me of a surprising discovery. The number of car parts you’d normally expect to be non-detachable became, in the hands of an excited and determined chimpanzee, quite the opposite.’

‘She could have got a job with Whelan the Wrecker, ’I said. How did they extricate her?’

‘Luckily, the window had been left wound down a fraction, which enabled the contents of a bottle of chloroform to be surreptitiously poured into the car. Although the window gap had been sealed with a cloth, more chloroform had to be obtained from the local chemist before Koko was finally declared to be well over the limit. Comatose in fact. ’

‘And Casey. Did he ever make a run for it?’

‘In 1934, Casey managed to escape from his captive state by slipping the chain that was around his neck. He was recaptured a short time later and secured by a keeper. ’

‘A chain around his neck,’ I repeated. That says it all, doesn’t it.’

Bit by bit, piecing together something of their way of life, the Taronga chimps were getting used to the sight of yet another strange white ape.

‘Daddy’,said a little girl standing next to me, ‘these chimps look so much like us.’

‘Many years ago, dear, there were apes from which the human race evolved.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘It means we grew out of these ancestors gradually to look and act like we do today.’

The girl looked a little confused and turned to her mother and said, “Mum, how is it possible that you told me the human race was created by God, and Dad said they developed from apes?”

The mother answered, “Well, dear, it’s very simple. I told you about my side of the family and your father told you about his.’

I spent a few hours more hours that visit in front of the chimps seeing a selfsame replication of human behaviours. Looking into their eyes, I saw a thinking, reasoning personality looking back. This was at a time when many scientists still believed only humans had minds and were capable of rational thought. As I looked into each yellowish brown iris, I experienced the overwhelming sense that there was a someone in there who was looking right back at me. It felt like looking into a mirror and seeing a part of myself in the reflection.

There are a lot of analogous behaviours between us and our our closest living ancestors. I couldn’t help but be amazed watching the chimps grooming themselves and interacting.

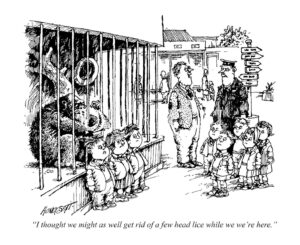

Grooming among our fellow apes is not only a means of social bonding but also a useful way of controlling those irritating blood sucking guests, nits and lice .

The link between us and chimps is intriguing.

These fellow beings showed me they were as capable of fear and jealousy as we are. I could see a reflection of human society and its social networking, the joys and pains of relationships and a parent’s devotion to duty.

As with us, it’s all about who’s friends with who, who wants to go out with who, who isn’t talking to you today.

I learned that though they are much stronger than us physically, they are no match for us in our capacity to apply our technological superiority for destructive purposes.

Before I left I asked the keeper, ‘Do you see someone like Bonzo or Casey as his brother’s keeper or his keeper’s brother?’

Both. I believe The Bible and The Origin of the Species both shed light on our fraternal closeness and need to protect each other.’

However Darwin showed that we and the chimpanzees are descended from common ancestors, winnowed by natural selection – and not independently created.

Conga at Taronga.

The next time I came back to Taronga Zoo with a class from Annandale North Public School in 1980.

‘Miss’, one boy asked the class teacher, ‘will we be seeing the dinosaurs?

‘I doubt it very much,’ she replied.

‘Did the cavemen kill all the lumbering dinosaurs?

‘Gee, Peter,’ I don’t know. It’s a little before my time’.

‘Actually, Peter,’ I explained, ‘the dinosaurs were dead millions of years before humans showed up. In fact, if the world were twenty four hours old, the dinosaurs would have lived in the last hour, and humans and other primates would have lived less than two seconds of that twenty fourth hours. We’re going to see some of these other primates.’

The children wanted to observe at close hand a troop of our closest relatives, not many pages back in the family album.

In their ‘show and tell’ activity one of the girls had brought a chimp doll from home and explained to the class why she chose that particular item, where she got it, and other relevant information.

I had coached them to sing the song from Dr. Dolittle, ‘If I could talk to the animals. Just imagine it. Chattin’ with a chimp chimpanzee. Think of the amazing repartee. What a neat achievement it would be.’

For these infants adults like myself were the first outside of their home with whom they’d spend a large, emotionally intense part of their day. And for them this day would prove exceptional.

After our arrival at the marvellous menagerie, as we approached their enclosure, this wild laughter rippled across the park .

‘Stop, hey children what’s that sound, everybody look what’s going down. ’

The sound was like dogs panting or someone having an asthma attack or hyperventilating. This made me imagine the first hoots of laughter from our common primate ancestor. When hearing it I can’t accept the view that laughter is a uniquely human trait. It’s just a different kind of laughter. Humans make it as they exhale, chimps make it as they breathe in as well. I visualised the facial expressions they were putting on.

I sensed from these expressions of excitement or arousal that it must have emerged long before humans split from the evolutionary path we shared with those who went another to become our primate cousins.

I feel that laughing has a pre-human basis, emerging earlier on than we did.

I was delighted to find that Bessie and Lulu still in the pink of health although that skin colouring on their bare faces, hands and feet had darkened with sun and age. They were seated together relaxing with Lulu running her fingers through her white beard. A male lay nearby on a nest of cardboard, basking in the sun. Several chimps engaged in grooming each other. One invited this procedure by offering his arm. One asked to groom another by quietly clacking his teeth together and inching towards the chimp he had in mind.

Others, their upper lips covered, lower lips drooped, played with each other, jumping around, capering and cavorting with abandon, wrestling, tagging and tickling, jousting with rope swings, just having a good time. All the time they were letting out this fast breathy laughter. They made soft ‘hoo hoo’ sounds that built into a loud ‘wha’ sound as they greeted each other. They pretended to bite and chase each other, playing keep-away. In a game that my children copied, one of them would sit with a stick or piece of grass sticking out of their maw while the other tried to grab it with their lips. In these japes of the apes one of the little ones casually stuck out its leg, tripping another one walking by. Another in a corner by himself let out a giggle when he decided to lean forward onto his head and elbows and propel himself along with his hind legs.

My pupils had come from one schoolyard to another, watching similar games and hi jinks that they got up to themselves. Like theirs, this yard was equipped with similar large sturdy outdoor playthings. The big attractions were the ones that rotated as well as the climbing structures .

And like our children, the chimpanzees liked to destroy things. They had cardboard boxes that they safely wrecked while playing in, squashing, ripping, and chewing.

‘Mr. Davis,’ one boy said to me, ‘do little chimps do dangerous things?’

‘Yes. You can imagine they can hurt each other or themselves jumping, swinging and breaking. Little chimps are very curious and are always investigating what they find around them. They have to learn not to wander to places where other bigger aggressive chimps might not welcome them. You kids also have to learn never to wander off without your parents. In the wild little chimps might see a snake on the ground and poke it with a stick, thinking its dead. That might not be the case and if its alive they could get bitten. They might investigate a fire and risk getting burned. Their parents will push them away from these dangers. It’s like when children like you come across matches or medicines. Matches can be very dangerous.

Only grownups can handle these so please leave these risky things alone.’

It only takes a few seconds for a fire to start and burn out of control. Tell a grown-up when you see matches and keep well away from them.’

And never, never try smoking cigarettes. Animals would never allow their youngsters to get smoke in their lungs during a bushfire.’

‘Or from cigarettes,’ said one boy.

‘ Of course. All these risky things are locked away by grownups for good reason.

Be very careful with things you’re not sure about.’

Some of Taronga’s resident chimps fossicked for fruit and nuts hidden in the logs and other knick-knacks. This exploratory exercise is a popular school playground activity. Then one young hirsute hero got on top of a log and jumped onto another below who tried vigorously to shake him off. At times it did seem like they were fighting but they did not hurt one another. Just like kids in a school, their laughing was a social sign that all the hair pulling, limb gnawing, face slapping and roughhousing was just for fun.

‘The big ones look very fierce,’ observed one boy.

I told him how ferocious they could be under certain circumstances.

‘Mr. Davis, if the adults got out and tore you to pieces …’

‘Yes, Tim?’ I asked, ready to console him.

“ …how am I going to get home?’

There were ongoing bouts of play, during which the chimps grappled, swung punches and occasionally tickled each other. They presented their backs to the tickler, scrunching their shoulders up to their ears, and raising their hands as if to shield their necks from the almost unbearable pleasure of it all. Some were tickled on their armpits, while others offered their feet to be tickled. One lay on the ground under a sheet. ‘What’s that lyin’ there,’ asked one boy trying to make it out.

‘To which another answered, ‘That’s not a lion. That’s a chimpanzee!’

When one ape displayed a gaping mouth, the equivalent of laughter, a second one adopted the same expression less than a second later, suggesting the mimicry was an involuntary display of empathy.

‘Oh my God!’ cried one of our kids, making the same face. ‘Aren’t they funny.’

We observed one cheeky chimp stealing a titbit – a dried apricot – from another with its back to him.

He restrained himself when it came to another who’d just been facing him. He would take from another whose eyes were averted, rather than one who had met his full gaze.

Looking furtively, he was accurately considering the visual perspective of others in his group.

The residents performed by acting silly in front of the children. They made a noisy show of banging, snorting, hooting, rocking back and forth, running, hitting and kicking things as they went.

‘This is what’s called a ‘display’, I explained, ‘and it’s normal for them. They do this because their emotions are running high and they’re trying to impress you. Displays are common when chimpanzees meet new chimpanzees or people. They are part of the many ways chimps have of communicating. Facial expressions, calls and gestures reflect how they get on with other chimpanzees and with people. Watch how they accept the keeper amongst them.

He demonstrated how they could handle a range of instruments and appliances such as pencils and locks. His verbal message that it was “time to eat” led to their excited chattering and assembly.

‘Understanding these methods of communication is essential for having a good relationship with them and staying in their presence with guardrails.’

The children in turn imitated the kind of sounds they heard them making. This little piece of pantomime attracted a crowd in a moment and the munchkins were shrieking with delight.

‘You should live here, too,’ one pupil said to another.

‘Look he’s smiling too’, one of the kids cried. The lazy sunbather was grinning from ear to ear.

‘It looks like he’s doing a funny smile, but it may not mean he’s happy,’ I said. ‘He might be afraid. Like some of you were on your first day of school. Away from your mum for the first time. He might be annoyed, just like you are when someone gets in your way.

It’s like when you watch a very funny movie or a scary one. If someone watched you through a one way window and didn’t know what you were watching, it might be hard for them to know if you’re filled with fun or fear. Under the right circumstances, weeping can sound like laughter and joy can look like fear. Or it could be mocking. Perhaps our emotional state can give rise to just a limited number of physical responses automatically, and it is only context that can make a grimace or a convulsion look positive or negative.’

Some of the chimps stuck their tongues partly out between their lips and gave us the bronx cheer.

‘Look, Sir, ’said one pupil, ‘he’s blowing raspberries.’

‘That’s all right. If they were angry they’d be spitting.’

‘What do we do then, Sir?’

‘Overreacting to such behaviour will only encourage it. If you jump away or yell at the chimpanzee, this will only encourage it. If you walk away slowly or ignore this behaviour, it will discourage it over time. It’s probably best to add a smile to your dial. It’s important to make the appropriate response to the environmental cues. An angry chimpanzee pressing its lips together tightly is a warning to stay out of reach. That’s when you smile and move calmly away. When danger threatens, we might smile trying to convince everyone, even our attacker, that nothing’s wrong. If we notice someone is dangerous, it’s probably best trying to appease them. We start smiling because we recognize that we’re in a hairy situation, and we want to signal the person who is dangerous that we have no wish for escalation. We are openly acknowledging fear and this may well be all he or she wants.’

‘Maybe he’s not happy because he didn’t want to be disturbed, ’suggested one pupil. ‘He may just want to be left alone. How would it make you feel if you were in your room or backyard and lots of people kept watching your every move?’

‘You’re very astute’, I said, giving him a pat on the back. ‘They’re on exhibit day after day in a controlled environment Chimpanzees, forced to live together daily, with no break from one another, are never fully able to relax alone in their space. It’s not natural for three or four adult chimpanzees to spend each and every day together. This must cause a a great deal of anxiety. We have to be respectful and keep these cousins of ours calm and happy. Even though we may love to see chimpanzees in zoos we really need to think about what is best for the animal. They need choices. ’

Enjoying the day out too was a big, burly man who played his flute for the residents. One of the male chimps began moving spontaneously, swaying rhythmically, hooting and even tapping his foot.

This suggested to me that dancing to music isn’t an arbitrary product of human culture but a response to music that arises when certain cognitive and neural capacities come together in animal brains.

As a child I had observed mirthfully a similar response from my pet sulphur crested cockatoo. It’s moves were much richer than just head bobbing and foot lifting.

I asked the flautist, ‘Have you been playing here long?’

‘Not here so much. However I used to play for the Wallabies.’

‘How old are the big chimps?’ one of the kids asked.

‘They are older than you. Lulu here is fifteen years old, ’I said pointing to her, and Bessie has a decade on her. ’

‘So why are they playing with little wheel barrows and throwing balls?’

‘A chimp has about the same mental capability as a 5 year old human. They think very much like you. And like you they are very clever and inquisitive. Chimpanzees need to be mentally stimulated. Think about what you or your brothers and sisters would do if you got bored and didn’t have any toys to play with. This means that they need all sorts of items to play with to keep them busy. ’

One pair of parents held their girls while looking at a chimp lazing in a hanging rubber tyre. The father explained to the elder one, ‘Chimpanzees are great apes like us. She wasn’t impressed.

I noted that the zoo now had an artificial termite mound. When the chimps plunged sticks into them, the reward was not termites but treats such as seeds, nuts raisins and apple slices.

‘Mr. Davis, ’said one little boy, ‘this chimp looks like our neighbour, Mr. Jones. ’

‘Maybe they were separated when they were born’ said Peter.

‘Peter, it’s not polite to talk like that,’ said another.

‘Why not? Peter replied. ‘The chimp doesn’t understand. ’

‘They have such funny little bums,’ said little Sarah .They’re not big like ours. Why is that?

‘These butts were made for walking,’ I said slapping mine. ‘The big muscles we have there connect to our bones to help us walk upright. The smaller ones in chimps help them to climb trees. But they get tired quickly standing, They need us to hold onto when walking upright.

‘That way we should stay good friends.’

‘I hope it will always be the story , Sarah.’

‘Mr. Davis, do the chimps have school?’

‘They learn from the word go. Chimpanzees learn from birth how to get along in a group and to follow the rules of social etiquette. They learn body language. They watch their mothers and other members of the group. Having an infant in the group allows other females to learn vital mothering skills.It doesn’t come instinctively.

Chimps learn everything from others and their keepers: how and what to feed, where to sleep, how to groom, how to ‘read’ other chimps’ behaviours, and how to interact with others. They are just as likely to imitate humans as the other way round. Remember the painting I showed you of of the chimps’ auto outing.’

‘Show me your shoulder, Tommy, ’the keeper asked the male who’d been jumped on and was now moving slowly. Tommy obeyed. ‘Good boy, ’said the keeper, giving Tommy a pat on the head.

‘They enjoy learning a variety of commands. They want to fit in. Only by learning appropriate behaviours will a chimp be tolerated by other members of the group and survive. The small ones are leaned on when they get out of line. Are you listening, John?’

‘Look at that one with the stick, Sir, ’said John. Is it trying to dig something up?’

‘It’s probing the ground with a twig, looking for whatever it may turn up. Chimps learn to use and modify a wide variety of objects in their environment for tools. In the wild they use a whole range purpose designed sticks. Some to dig up roots. Others to get honey from hard to get into bees’ nests. It’s now believed they fashion spears to hunt bush babies. It’s now believed they use logs to crush things with. They make sponges by chewing leaves to make them more absorbent. Then they dip for water. You see our residents here. Those cocktails they’re sipping up with their own homemade ‘straws’ include fruit juice as an incentive. In the wild they use stones and branches as hammer and anvils or as weapons. Using stones is off limits here in case one of them throws them around. ’

‘The keeper would have to discourage monkey business like that, wouldn’t he?’

‘He or she would try to encourage them instead with rewards for good behaviour, ’ I said, referring to positive reinforcement. He or she aims to link the desired chimpanzee behavior to something the animal likes. People can make them act the way they want them to by ‘catching’ them doing something desirable, for example sitting down in the right place, going where asked, and praising or treating them with a small food reward. By using a specific word or gesture when the chimpanzee performs the desired behaviour, people can eventually use the word or gesture to ‘ask’ for the behaviour. Letting chimpanzees know what is needed of them, and giving them a chance to cooperate, gives them some control over their lives.’

The way we treat apes had come a long way since my visit in the mid-sixties.

Our treatment would come a long way still, developing from a sideshow of exhibits into a wildlife sanctuary.

Along the way they would be used for research in laboratories. According to Sir Colin Blakemore, professor of neuroscience and philosophy at the University of London and a long-time defender of the use of animals in research, discoveries in the 1950s and 60s revealed how chimp brains were ‘uncannily’ like those of humans.

‘The structures, the folds, the similarity was amazing,’ he said.

Great apes were used as models for humans, but the model came back to bite the researchers because of that shocking similarity.

It became harder to justify conducting experiments on chimps. A ban became the inevitable outcome.

Before my class and I left, the primate keeper gave us a summary of developments in the care of chimpanzees.

‘A good zoo recognises its limitations in what it can hold,’ he said, ‘and the need to change and improve.

The zoo recognises that chimpanzees should be kept in a large community situation. Cages are morphing over time into lush enclosures that try to resemble the natural habitat. These enclosures now aim to keep humans and chimps more distant from one another. Increasing the distance between humans and chimps means that feeding the animals in zoo has been discouraged. This decreases disease transmission as well as giving the chimpanzees a place to lie doggo if they do not wish to be viewed by us. Chimps are very social and live in multiple family communities, a bit like a suburb. They like to know who is in their community, and who’s who in terms of ranking. While they are happy to meet up, they’re also pleased to be able to get away from each other. The latest enclosures being built are being purpose-built to cater for all these behaviours and requirements.’

‘Larger enclosures allow the ability for multiple chimpanzees to be housed together, their mothers’ milk when we consider that in the wild chimpanzees could always sit with a friend if they wanted to. Chimps, like humans, are social creatures and need social groups to live in.’

As he spoke several of his charges formed a processing line, moving rhythmically one behind the other, turning into a circle. All were plainly getting a kick out of it.

‘Do they eat well compared to before?’ asked one pupil.

‘Efforts to improve captive welfare in apes have become increasingly focused upon the need for fresh fruits and vegetables, variety in the diet. Modern zoos like ours employ the knowledge of zoo nutritionists who plan the diets of all animals in the zoo. We are always working out more types of enrichment activities. All this is very important for their health and well-being.

As a result of these improved conditions chimpanzees have been more successful in zoos. By learning more about how to take care of the chimps in zoos people have become more aware of the need to protect the chimps in the wild. More and more often zoos promote conservation efforts to try and help wild populations.’