“May they not forget to keep pure the great heritage that puts them ahead of the West: the artistic configuration of life, the simplicity and modesty of personal needs, and the purity and serenity of the Japanese soul.”

Albert Einstein,1921.

Ending war and making a better future is not a responsibility we can say belongs exclusively to the government, each one of us must play our part.”

Leonard Cheshire

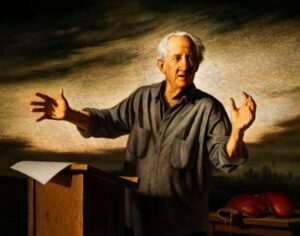

I met up again with Tom Uren, Gough Whitlam’s Minister for Housing, in Balmain Hospital after my stroke when he came to visit his cousin in the bed next to me. I had met him on a number of occasions on buses and while walking around and shopping in Balmain.

Born into the poverty-stricken Balmain community, Tom helped shape every transition it has seen. Through the artistic and political hub of the 1970’s to the beautiful harbourside destination it is today. Touch wood!

His mouth, set above a fighter’s chin, seemed ready, given half a reason, to smile at any time. I was riding the 433 bus with him one day when a guy said to him, “Heyyy, I saw you on TV.”

Tom stood up, bowed his head and said, ‘Thank you,’ with a big smile. He had reason to feel good. He had a love for people with all their eccentricities and all their shortcomings. Then the guy turned to someone else on the bus and said, ‘Heyyy, I saw you on TV.’

Tom enjoyed something that most rich people would always lack-the joy of being widely respected and loved.

‘That always made me feel aIl right. I wouldn’t have missed that for the world.’

I said to him, ‘You’re looking tip top despite your legacy of beri-beri and malaria.’

‘Ah that gift that keeps on giving.’

‘So Tom, what keeps you so sprightly?’

‘Walking down the street, I see the beauty of peoples’ faces. Nothing can beat the joy that people give me,’ Tom confided to me. ‘I don’t have to buy it. People give it to me.’

His cousin, Alan, had lost the first of his two legs and sang constantly in our Balmain Hospital ward to distract himself from the pain. He was happy when I joined in, being well versed in the golden oldies of his generation. When Tom approached, Alan burst into something very personal:

‘I’ve been working on the railroad

All the live-long day.

I’ve been working on the railroad

Just to pass the time away.’

Tom joined in with another verse:

‘I’ve been working on the trestle,

Driving spikes that grip.

I’ve been working on the trestle,

To be sure the ties won’t slip.’

‘You know that song for sure, Tom,’ said Alan.

‘I suspect I had a part popularising it in Japan. Their troops listened to us singing it. It’s now a very familiar nursery rhyme there. Same melody but different title and lyrics.

‘What do they call it, Tom?’ I asked.

‘It’s known as “Senro wa tsuzuku yo doko made mo”. It means “The railroad continues forever”. It’s used at certain railway stations to announce arriving trains. Their lyrics describe the happiness of the journey.’

‘It wasn’t such a happy journey for you, Tom,‘ said Alan. ‘Slaving on the Burma-Thai railway. A captive of the Japs.’

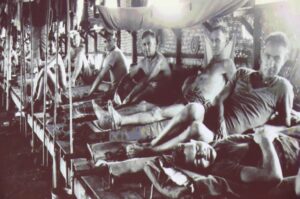

‘It was certainly no holiday camp. This was me, ’he said showing me a photo of him and his fellow prisoners in their sleeping quarters. ‘I’m the skinny one third from the right.

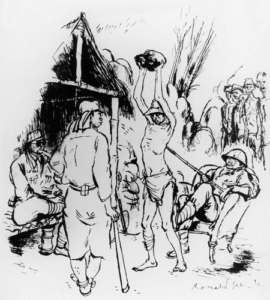

We were starved, beaten and worked close to death. I was forced to swing a heavy sledgehammer, a mate holding a drill, to form holes for dynamite. This was to carve the deep mountain cutting known among the slave gangs as “Hammer and Tap” and, more descriptively, as “Hellfire Pass”.

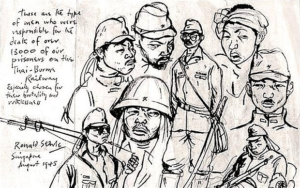

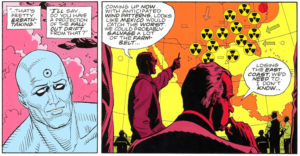

I showed Tom some illustrations by artist Ronald Searle, a fellow survivor.

‘It certainly seemed it would continue ‘til Doomsday.

As Ronald says, they were like the Nazis. Especially chosen for their brutality and ruthlessness. Many of my mates didn’t make it. I’m happy to have survived.’

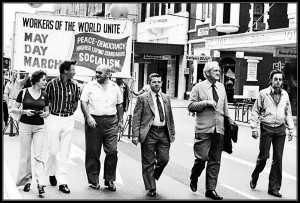

So too were most Australians. A veteran of Changi, Tom packed a punch providing affordable public housing to many lower income families and putting land on the block for young home owners at a price within reason. An inveterate idealist and confirmed socialist through and through, he carried the torch so his ideas would not be forgotten. Tom retained his position of moral standard bearer in Australian society.

His was one of the most instantly recognisable faces in Australian politics. To sit with him on a bus or train or in a restaurant was to witness a steady stream of admirers of all ages and all political persuasions coming up to shake hands or exchange a few words. In an age where politicians gleefully degrade themselves and their office for a smidgen of reality TV attention or bend over backwards for the smallest sprinkling of stardust, it was a relief to consider Tom’s dignity. He showed that it’s not necessary to sell out one’s good values and become morally corrupt as part of the machine if one is to succeed in politics.

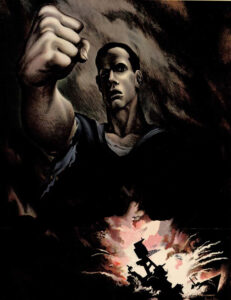

Unlike most of his parliamentary colleagues, this former boxer with his dynamic southpaw punch stood firm and spoke out in support of peace and nuclear disarmament.

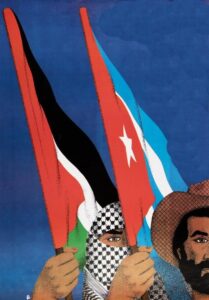

He demonstrated publicly that he backed Cuba, Vietnam and a Palestinian homeland.

‘Who better than the Vietnamese to pass on the torch of resistance to colonialism than the Vietnamese, Tom?’ I put it to him.

‘We have to hand it to them, Allan. In our own lifetime they’ve seen off the French, the Americans, the Pol Pot regime not to mention the Chinese.’

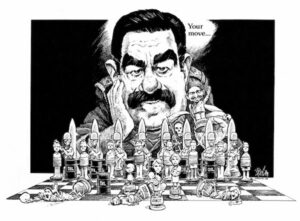

Tom opposed the invasion and occupation of East Timor by Indonesia. Like Tony Benn during the Gulf War he travelled to Iraq to negotiate the release of Australian hostages, the ‘guests’ of Saddam Hussein.

‘You weren’t helped much by Mrs. Thatcher’s bellicose rhetoric were you?’ I said to him. ‘She really got her claws out.’

‘Her aggressive stance didn’t help our effort one little bit. In fact She was a bloody menace. To make her mark in a male-dominated political environment, she overcompensated by acting even tougher than male PMs. had been and would be.

Thank goodness that there were not many other world leaders that were saying similar things. We didn’t need anybody to enrage issues at that stage,’ he said.

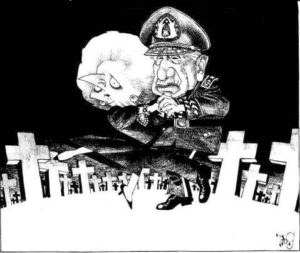

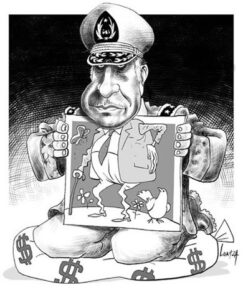

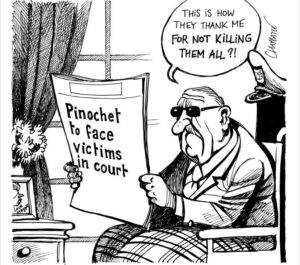

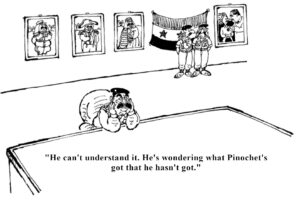

‘And who was she to talk of Saddam’s cruelty when she had been hand in glove with the Chilean terrorist for many years. She fully embraced this Chilean mass murderer’s dance of death. ’

‘Let’s not be too harsh on the poor man’s memory, Allan, ’Tom said sarcastically. ‘He became very frail and was happy to be seen as a peacemaker by his financial backers.

‘You have to admit many people were very ungrateful for all he had done for them.’

‘How do we explain the different way the Empire treated him compared to how they dealt with Saddam Hussein?’

‘The thing is Pinochet always stayed true to the Empire whereas Saddam was no longer dancing to it’s tune .’

Don’t forget Saddam had failed them in the war against the Islamic Republic.’

‘He failed it even after he’d accumulated a huge supply of weaponry.How do the US and the UK know this?’

‘What do you think?’

‘They kept the receipts. Did you see any signs of military build up when you were there?’

‘We were limited in what we could see but I imagine they were preparing their stock of Scud missiles.’

In the exercise to secure the release Tom was helped by the persistence and co-operation of the Vietnamese envoys.

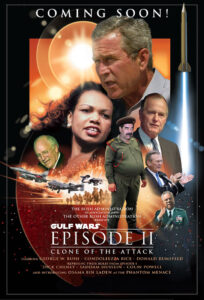

‘They know better than anyone the worth of American government declarations,’ I said to him. ‘The White House keeps announcing the end of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan,’ ‘They still declare ‘Mission Accomplished’ but the body bags say otherwise.

‘It’s all over bar the shooting. This continuing anarchy creates its own rationale for returning.’

‘They’re always planning on shooting yet another sequel to their horror franchise.’

‘Their logic being : ‘We have to go back to Iraq to rid it of the Al Qaeda that wasn’t there before we got there to rid it of Al Qaeda.’

‘It’s like the up and coming ISIS, the ones to watch now. ISIS is itself a product of American presence and occupation in Iraq — it’s been hatched in the U.S. military prisons.’

‘The Americans promised so much yet that’s what they delivered. They said if Iraq got rid of Saddam Hussein, they would help the Iraqi people with food, medicine, supplies, housing, education – anything that’s needed. Isn’t that amazing? The White House finally came up with a domestic agenda – and it was for Iraq. Maybe they could bring that stateside if it ever works out’.

Tom’s instinctive reaction to the forced end to the Canberra Spring, when his Labor administration was overthrown, he told me, was to call for a national trade union stoppage. His colleagues, like their counterparts were more cautious.

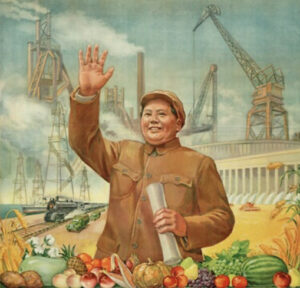

There was a real carry on in Parliament over Tom’s visit to China in 1960. Tom had perambulated around the cities, even the back streets. He saw no food queues. He deemed the administration as effective, having restored a country ravaged by civil war and secured the basic necessities of life to its people. ‘Things may not have been as rosy as Mao portrayed.’ he told me, ‘China was undergoing the birth pains of rapid industrialisation and collectivisation, but like every government it pointed to it’s achievements rather than it’s problems.

After his return, advocating recognition, he prepared a slide show travelogue which he took all over Australia. My father took me to one in Sydney where Tom used a hand clicker to advance to each slide: ‘Here I am at a market crammed with fresh produce. As you can see it’s exotic fruits and fresh spices form a kaleidoscope of colour.’

His secular convictions never stopped him building an alliance over social issues with the Sisters of St Joseph, the Catholic order who admired his humanity and called him an honorary Josephite.

‘Since you’ve been out of politics, you’ve had a lot on as ever, Tom.’ I said to him once on the 433 bus heading for Balmain.

‘I’m not out of politics, Allan, I’m out of Parliament.’

‘Like Tony Benn.’ I said aware of the distinction. ‘Freer to put up a fight for social justice, human rights, and the world environment. Not exactly the cardinal rule for the typical politician.’

They have a much simpler rule: ‘Never get caught in bed with a live man or a dead woman.’

‘Whether it be here or in the UK parliament, they also have another rule: Never admit your goal to carry out nationalisation of industries,’ I said.

‘ A conversation that supposedly took place in the House of Commons bears this out.’ Churchill is said to have encountered Clement Attlee at the urinal in the Members’ toilets in the House and shuffled as far away as possible. Attlee said: “Feeling standoffish today, are we, Winston?” to which Churchill replied with characteristic wit: “That’s right. Every time you see something big you want to nationalise it.”

‘Parliament’s not the most edifying arena is it, all those lies and compromises.’

‘Don’t I know it!’

How can anyone justify its existence with all that?’

‘The best its defenders can come up with is that it somehow works, that it’s contained.’

‘By what?’

‘Contained by precedent and procedures. And small threads of goodwill.’

‘There wasn’t much of that shown to a man of your dimensions at one time by some who should have known better,’

Fighting the good fight involved a long battle to successfully clear his name after being accused in the Packer media of being a treacherous stooge, of being privy to Soviet intelligence.

I paid my respects to him at his home in Balmain after my hospitalization.

‘You’ll have to excuse my bias, Tom, I said as he took my arm. ‘My right side is more developed than my left.’

‘That’s all right,’ He replied. ‘We can strike a balance. As my doctor observed after I returned from my Japanese working holiday, my left side is more developed than my right. Everything I had been doing with my left arm.’

Sitting at his table, I thanked him for promoting restoration and re-use of derelict inner city areas.

‘Your department did a great job in renovating the Glebe estate, ensuring a broad social mix. I admire the way this included housing for those women who squatted two properties and set up a refuge for abused women.

Tom said ‘Oh my godfather, I wouldn’t want my mother or wife to live under such difficult conditions.’

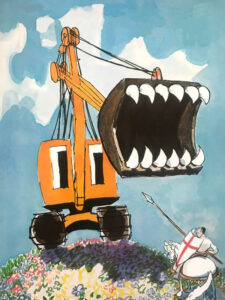

All his life Tom combatted environmental degradation, and urged reclamation and protection of Sydney’s priceless foreshores.

‘Much obliged for helping preserve Sydney’s beauty and public spaces, Tom, for all Australians and all who follow us. It made getting a roof over my family’s head more possible’.

‘In what way?’ he asked.

‘By seeking a freeway system out of the city westwards, alternative to that planned which would have cut through many heritage properties, you blocked the destruction of what was to be our house.’

‘Allan, did you know that the giant silo it passes, the pinnacle of which offers a magnificent view of this tract, was built by my father, a builders labourer. Whenever I pass it, I think of him.’

‘When I pass it, Tom, I think of my boys who, I found out later, used to climb up it to enjoy that view.’

Tom’s own house has a magnificent outlook facing due north with a picture frame view of Ball’s Head and a 160 degree view of Sydney Harbour. ‘Sometimes I wake in the morning with a tanker in the front yard.’

‘The ghost of Menzies coming back to haunt you’, I joked. Ming had told Tom back in ’62, ‘I’m not lazy. I would rather be a tanker than a canoe.’ Tom had said in a speech that Ming was overfed, overweight and lazy.

Ming was heading that corpulent way when he came across me back home.

‘I have to give Menzies credit where credit’s due. He was without dispute a good captain of his ship. He kept it on an even keel, the crew in line. though he never generated the engine room.’

‘How do you mean?’

‘He wasn’t one to generate policies with visionary programs. Ones like those put forward by Malcolm Fraser towards the First Nations people.’

As we gazed out at the water, a rowing boat came into view.

‘Did you ever row, Tom?’

‘No never. I didn’t go to a Great Public School. Just your regular lowercase public school. Rowing was Gough’s preferred sport. He pointed out it’s an extraordinarily apt sport for men in public life because you can face one way while going the other.”

‘That’s a a good line, but it cannot be applied to the man himself.

‘True. He has always kept going forward, and his eyes have always been fixed on the stars.’

‘And it couldn’t have been applied to Russel Ward.’

‘The historian?’

‘The very one. Another perceptive commentator on the place of rowing in the ruling class mystique—

‘—And the place of religion in the fooling class psyche—

‘— And their attendant bags of tricks.’

I brought Tom up to speed with what I knew of Russel.[See ‘Halcyon Days’]

‘So ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ went to a posh school too.’

‘He did. And like Gough, he became steeped there in religious knowledge.’

‘Fellow travellers on the road from Canterbury. Getting through somehow.’

‘By speaking in tongues. And like Gough and like you becoming steeped in all kinds of unholy things.’

‘You can say that again- but then you have to fight your way out of that mire and consider holier things.’

‘As for holy things, Tom, one of the great passions of your life has been beauty. Could you explain how that evolved in you, that love of things beautiful?’

‘As a youngster, starting school at 13 and then working at thirteen and going on the Manly ferry every day, I had a great opportunity to absorb this beautiful Sydney Harbour. I’ve had a lifelong love affair with Sydney, I mean it just captures you and the more you look at Sydney the more I love it. It’s national parks on the south and the west and the north and the beautiful angophora trees.

Take a ferry from Palm Beach up to Bobbin Head, there’s that lower part of the island where you should go in January when those angophoras peel their bark and they show that lovely salmon bark trunks. There’s something about the beauty of our city and the beauty of Australia. The east coast of Australia is a paradise, and really, we should be very, very careful that we don’t over-exploit it, that we really do feel, all of us should say, it belongs to all of us, it just doesn’t belong to any individual, and we should be very protective of our beaches and our mountains. It’s such a beautiful serene environment and we should do something about — make sure that we do protect it properly.’

Tom’s home reflected this love of his environment, man made yet in the raw. His simple open plan single story house has a central room with an expansive atrium and a high open ceiling. As soon as I entered I got a sense of openness and freedom.

‘Both internal and external walls are made of solid blackbutt from northern N.S.W.’ he pointed out, embracing them. ‘The ceiling is Tasmanian celery top. There’s no nails in this house except in the flooring.’

‘So, what stops the wolf huffing, puffing and blowing it down?

‘The remainder of the house is kept together by screws and bolts, mostly brass. This way the house can be re-cycled. It’s designed to capture the maximum amount of light in winter as you can see. In the summertime or on pleasant days in winter the house opens fore and aft with sliding glass doors, floor to ceiling, concertina-ing into one another. This magical house gives me a special serenity and is a joy to live in.’

Tom showed me his lithograph and watercolour of Ball’s Head with the loving inscription on the back from Lloyd Rees.

He proudly showed me a beautiful painting by Clifton Pugh called ‘Early Spring’. ‘This is very precious to me. I’ve been in the bush with Clifton, and when you went into the bush with him his eyes observed things that you’d never see. He’d just pick that up and talk about life through a little flower there or some such thing, and it was this ‘Early Spring’, this beautiful piece of abstract painting he did, that I couldn’t help but buy even though it stretched me for every penny I had at that time.’

‘You wouldn’t have been able to afford Blue Poles,’ I said referring to the composition that does not make visual references.

‘One young female Liberal philistine expressed annoyance to me about it. She’s said it’s nothing but wallpaper. Then again she complained tirelessly about all abstract paintings.

‘What a lot of rubbish! I don’t know much about art but I know what I don’t like. I’m sure a chimp could do better. It’s nothing more than the indulgence of a artistic minnow dripping and pouring paint around.

‘Cry me a river. How can you dismiss his work as unimportant?’ I replied, ‘It’s hanging in the National Gallery.’

‘Well, Tom, so is toilet paper.’

‘Don’t look such a gift horse in the mouth. It’s now worth hundreds of times more than what we paid for it. Now who’s your sugar daddy?’

‘Not everyone gets abstract paintings, Tom. Take Bob Hawke for example. He has had difficulty understanding the cubist portrayal of his friend and rival, Paul Keating.’

‘ Hawkie has to keep in mind how much Paul developed over his career. He was originally a very narrow-minded young man who later matured and became far less socially conservative.’

‘He certainly did. He passed Australia’s first national native title legislation.’

‘I had some questions to put to Tom. ‘You worked as a manager for Woolworths, Tom. How did your socialist ideals take shape there?’

‘You have to remember I started there after making tyres as a trainee cleaning the floors and windows. As with other activists of the time, I improved my position in Australian society as the opportunities presented themselves. But as my material position improved, I still believed that it was right and good to lend my financial and physical support to the causes I believe in.’

‘Where would you say these ideas sprang from, Tom?’

‘They derived not from book learning but by an everyday rule of thumb approach based on my experience. I draw my ideas from my own philosophy and personal feelings and they reflect those of great socialists in the tradition of William Morris.’

‘Even your home reflects his thinking, Tom. He said ‘Have nothing in your home that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’

‘My mum was the very picture of both these qualities. She was a great influence.’

‘Every child needs a great deal of love for the first five years of their life, don’t they. To give you a sense of emotional security about who you are and where you are.’

‘My mother gave heaps of warmth and love and affection to me. I can remember her talking, even as a very young boy, about the poorness of our house because we used to have to pawn. The old landlord, who was a pillar of the church, used to come round and ask, ‘Mrs Uren, is there anything else you could pawn to pay for the rent?’ And I might tell you that all we had left in the bedroom was the normal bed and butter boxes each side and, so, it was very, very grim conditions.’

‘I might say that that in those days, you know, there were no unemployment benefits or anything at all like that. If you really wanted to get welfare, you had to go before the ‘nice’ people of the community, to see whether or not you were worthy of welfare. And those things always stayed with me. Because my mother had told me about it. But normally my mother worked with my Aunty Mary as a barmaid, between having children, because you see in those days the society wouldn’t accept a pregnant woman behind the bar, and that’s why at the most needing period of our lives was the most difficult because my mother couldn’t go out to work, my father being out of work.’

‘And then there was the war as your university of life.’ I said.

‘Needless to say it was my experience in the War, Allan, as a prisoner of war, where my deepest ideals grew. I explained this in my maiden speech in the House. Our men, my soldierly comrades, were held together by team work. We expected everyone to work to the best of their capacity. And that meant carrying those who were unable. I’d say to the men, listen, come on. We’ve got to help so-and-so. He’s a bit crook. I would always try to help the bloke who was a bit smaller or wasn’t quite so well. We always knew who was genuinely crook, and would try to help as best we could.’

‘In our camp the officers and medical orderlies paid the greater part of their allowances into a central fund. The men who worked did likewise. We were living by the principle of the fit looking after the sick, the young looking after the old, the rich looking after the poor. By the way, would you like some refreshment, Allan?’

‘What about some pap, old chap?’ I asked, mentioning the rice flavoured water passing for his breakfast that had to sustain him for walking six or seven kilometres to work.

‘I’d be cruel to offer such gruel. You would wee and you’d wee but with hardly no stool.’

‘I’ll give it a miss, I need to make crap,

I can do without such a lousy bum rap.’

I settled for some coffee and cake.

‘How do like your coffee, Allan?’

‘Like my women. Bitter and murky,’ I joked.

‘A few months after we had arrived at Hintok Road camp’, continued Tom, ‘a part of a British ‘H’ force arrived. They were about 400 strong. As a temporary arrangement they had tents. The officers selected the best, the non-commissioned officers the next best and the men got the dregs. Soon after they arrived the wet season set in, bringing with it cholera and dysentery. Six weeks later only fifty of those men marched out of that camp, and of that number only about twenty five survived. Only a creek separated our two camps, but on one side the law of the jungle prevailed and on the other the principles of socialism.’

Tom put down the difference to that of leadership. It was our commander ‘Weary’ Dunlop who made all the difference.’

‘Tell me about him, Tom.’

‘A courageous leader and compassionate doctor, ‘Weary’ restored morale in those terrible jungle hospitals and prison camps.

He defied our captors, gave hope to the sick and eased the anguish of the dying.’

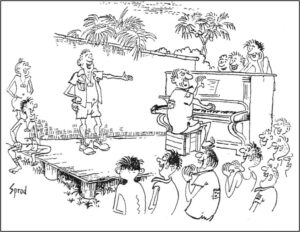

‘He organised the men to hold concerts to lift their spirits, my father told me.’

It was his hope that their musical talents would transport both their audience and the performers singers beyond the confines of the camp and help to give them some of the strength they would need to survive the nightmare of captivity’.

‘This must have been a vital source of spiritual and musical sustenance to his fellow prisoners.’

‘It meant that ‘Weary’ became, in the words of one of our men, “a lighthouse of sanity in a universe of madness and suffering”. His example was one of the reasons why Australian survival rates were the highest.’

‘Their treatment didn’t increase your chances of reaching old age, did they.’

‘I endured the sadism and brutality of the Japanese military in their prison camp, on the railway, and in Japan.’

‘What did they do as a rule, if I might ask?’

”Let me just say they weren’t those of the Marquess of Queensberry. I was hit with open hands, closed fists, pieces of wood, iron bars and bamboo about two inches in diameter. I was sent to a place called Saganoseki and forced to labour in a copper smelting works. There I came into contact with ordinary Japanese people. Working alongside them, I found them to be comradely and considerate.’

‘Some would find this hard to believe, Tom. Some hate them with a passion.’

” I always point out to them what Dr. King said, “Hate is always tragic. It disturbs the personality and scars the soul. It’s more injurious to the hater than it is to the hated. So many people are crook on their fellows, but I just look for the love in people,’ said what some see as a sensitive new age guy, long before there was such a thing.

‘Did you find any such love amongst these people brainwashed to act so cruelly?’

‘The older people were the more gentle, having been spared the dehumanizing indoctrination of this oriental fascist state.

After each shift all workers from the factory would bathe in the traditional communal bathhouse. Before, I would willingly have exterminated the Japanese race from the face of the world. In the factory the human feeling in my relationship with them came back. I developed forgiveness and understanding.

The Nukes of Hazard.

The Japanese were as much victims of militarism and fascism as anyone else, ’I said.

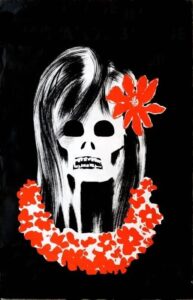

‘They suffered so terribly from those atomic bombs, that’s for sure. Such large numbers died from the effect of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. People have to be educated about these so it never happens again. Teachers can play an important role in conveying this message. How did you approach this Allan?’

‘I used the story of Sadako to get this lesson across. This story that has become familiar to many school children all around the world.’

‘The Japanese schoolchildren I have spoken to know it off by heart. How does the story go down with our children?’

‘Children find it hard to relate to the suffering of many thousands but can to the suffering of one. My approach was while reading excerpts aloud to have the children making paper cranes. I showed them how to simply transform a flat sheet square of paper into a finished sculpture.’

‘There’s a thought. You kept their hands busily folding so they could concentrate and not become distracted and fidgety.’

‘The advantages of this artform are manifold. To begin with the children knew I had a black belt in origami. Plus, there’s plentiful supplies of paper available. You’ve just got to ask any school secretary for recycling paper.’

‘It was less abundant for the young Japanese child. She used whatever paper she could get. She used the paper from medicine bottles, sweet wrappers, and left-over gift wrap paper.’

‘They make very simple, modest economical gifts, Tom. And being non-commercial, people appreciate them all the more because of the personal thought and effort put into making them. In fact, I brought along one I kept from long ago,’ I said reaching into my sample bag in of education materials. It’s only a little thing but I hope you will accept it with my warm compliments.’

‘I appreciate that, Allan. It might be little but it’ll be a little treasure to remember you by.’

‘Tom, as you well know Sadako made a vast series of the cranes.’

‘The Japanese believed that when accompanied by a wish they can lead to a cure.’

‘So, what would be your wish if this one alone could do the trick?’

‘I wish that the longterm effects of the malaria the Japanese High Command exposed me to would go away. Of course, they’ll be with me ’til I’m carried out of here in a box. On a more realistic level, I wish that Japan never ditches it’s pacifist constitution which revisionist forces there are pushing for.’

‘After all the suffering they’ve been through, you’d expect the lesson to have sunk in completely.’

‘They cling more tightly than ever, especially in their textbooks, to the myth that the war was a noble if mistaken undertaking. It’s about time that the Japanese people and the Japanese government examine the crimes they committed in the thirties and forties.

They should at least let their school children know in their education system so that they understand the crimes that were committed in that period. It doesn’t help that the U.S. is aiding and abetting them in this revision.’

‘Tom , from where you were, you saw the crimson glow of the sky, of that second bomb dropping. You’re like Leonard Cheshire, one of the relatively few people on earth who knows what a nuclear bomb exploding on people looks like. What impression did it leave you with?’

‘It reminded me of those beautiful crimson skies of sunsets in Central Australia, but magnified about ten times stronger, oh so vividly. It’s never left me. In the long term, I saw the dropping of the atomic bomb on them as a crime against humanity.’

‘What about the argument it was necessary to shorten the war?’ I put to him. ‘We had to, because the Japanese resistance was fanatic, and we would have lost many lives taking Japan.’

‘It was morally indefensible, I repeat, but also militarily unnecessary The Japanese were already beaten hollow. They were looking for a way out of the war. The United States knew they had got the best of them. It had already been bombing Japanese cities. It had firebombed over a hundred cities.’

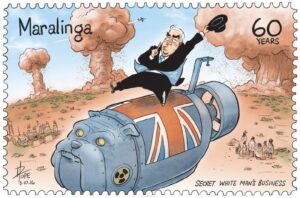

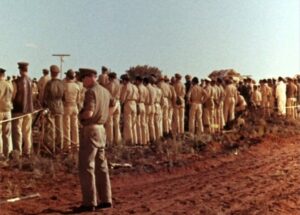

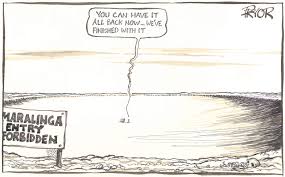

‘You got up on your hind legs in Parliament on the question of the Maralinga atomic tests carried out by the British.’

I asked many questions on this matter and called for a full enquiry into what had gone on there. The more I asked the more it appeared like a Pandora’s box. Public concern has been answered with a series of untruths and half truths about what testing took place and slick assurances about the nuclear waste which now remains and the hazards at present. The Liberal government simply would not or could not give straightforward answers to the most basic questions.

I agitated about the cover up of the secret tests at Maralinga in the fifties and sixties. Very little consideration was given to the inevitable aftermath of the tests on Australian soil.’

‘It will cost the Australian taxpayer for policing the waste for the 300, 000 years before it loses it’s toxicity. How much are we talking here? ’I asked.

‘‘Heavens knows, and that’s only part of the bill. Apart from our own aborigines and the native fauna, the radiation would have affected the health of troops nearby.

It would have affected the airmen flying through the atomic clouds.

It would have affected observers.

‘It will cost the Australian taxpayer for policing the waste for the 300,000 years before it loses its toxicity. How much are we talking here?’ I asked.

‘‘Heavens knows, and that’s only part of the bill. The fallout would have affected our food chain. The tests raise big concern about our national sovereignty. There are many unanswered and unresolved problems.

Many of the issues I raised were addressed in the Royal Commission .

‘You never forgot your fellow POW survivors, did you. For many years you fought for them to be granted extra benefits.’

‘How could I forget them. They died younger and suffered greater illness than other returned servicemen. Important things came to the fore in the prisoner of war situation.’

‘The question of our future as a species.’

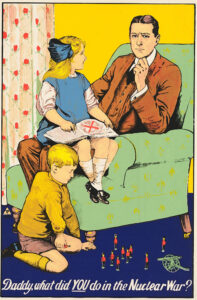

‘The effort to halt the nuclear arms build-up remains more important than ever.’

‘Especially now the nuclear torch has been passed on more widely.’

‘‘We have a duty to pass on the torch of disarmament for everyone to carry so as to stop such a conflagration.

In the great anti-nuclear marches I’ve been privileged to take part in, I have seen that collectivism of the human spirit. If we don’t act together, we won’t survive. We have to rid ourselves of the rat race in which we’ve become bogged. We have to start coming together as human beings to try to prevent the terrible threat to our planet and ourselves. I don’t have to tell you about that of course, do I.’

I had helped organize the annual rally through Sydney in the early 1980s as a member of the Hiroshima Day Organising Committee and remember well Tom’s place at their head. Our tasks as a committee were to co-ordinate the various contingents of thousands to march through the streets under the slogan ‘Hiroshima Never Again’ and to focus on the many issues related to this, such as the push in Australia to talk up nuclear energy. Our demand was to prohibit the development, testing and possession of nuclear weapons, especially in the South Pacific.

We wanted to ban using or threatening to use these weapons. Our demand was for the dismantling of existing ones.

‘We have to not just ban nuclear weapons but the very idea that our freedom somehow depends on the fear of annihilation.

An absurd and obscene idea.

It makes me want to get my shirt out.’

‘I share your anger. People have been accepting nuclear weapons as legitimate tools for providing security for, you know, over sixty years now.

Since they came into being, there has been an impulse to embrace them and see them as saviours, that prevent war, keep the world going, maintain authority on the part of the nuclear weapons-possessing nations. This extreme nuclearism is a kind of embrace of the weapons to do everything that they can’t do. They’re no safety blanket. We have to keep trying to change that mindset, really. It’s not acceptable to threaten to level entire cities, destroy countries, human beings, just to keep yourself secure.’

‘It hasn’t deterred North Korea and Iran from trying to go nuclear.’

‘In each nuclear-armed states right now, all of the nine ones are constantly pushing to upgrade and modernize. But the rest of the world is going in another direction. Over 120 countries have negotiated and concluded a treaty that prohibits nuclear weapons. So we see these two parallel trends in the world, where a few countries, the outliers, are clinging onto these weapons of mass destruction, while the rest of the world is moving beyond that, towards a new type of security policy that doesn’t involve threatening to indiscriminately murder civilians.’

‘What about the peaceful use of nuclear power?’

‘How peaceful was it in Chernobyl?

How peaceful was it recently in Fukushima ? It was part of a triple threat to the poor Japanese-a major earthquake followed by a fifteen metre tsunami, the disabling of the power supply and cooling of three nuclear reactors, causing the melting of all three cores in the first three days.

‘These ‘accidents’ raise many, many issues I’ve become concerned about, particularly the problems of nuclear waste and uranium mining in Australia. It’s relation to nuclear weapons is inseparable. The role of Australian uranium mining in the world nuclear fuel cycle created problems relevant to our sovereignty, our economy and the rights and welfare of the aboriginal people whose land is affected. Until all the problems in its use are figured out, we should ensure it stays in the ground.’

I asked about his feelings on A.S.I.O. He discovered back in the sixties it had supplied the misinformation ‘linking’ him to Russian intelligence. ‘The sickness of their allegations hurt, exposing the depravity of their minds. They set about to destroy my character and my life.’

‘That must have been so depressing. How did you get out of that?’

‘To get out of that depression I listened to a recording of Paul Robeson, talking when he was in Paddington Town Hall in 1960. I’d play this back and coming through was the compassion of this man’s voice, his soul. He really put it in. Not only was he struggling for justice for himself, but for the oppressed people of the world. With guts and determination. I said to myself, “Get up and fight the bastards, Uren.” I know that Paul went overboard with some of the Soviets. A lot of other people did at that period of history, but I have so much respect for him.’

‘What were the tactics of those A.S.I.O. scoundrels?’

‘They condemned me by using their journalist operator and a backbencher to carry out their smears and allegations. The first in a major national newspaper, the second in the House, protected by parliamentary privilege.’

‘Bjelke Petersen mastered these arts of damaging reputations, didn’t he.’

‘He appeared to be a buffoon but he learnt a thing or two from Joseph McCarthy. He accused political opponents of being covert communists bent on anarchy. He observed: “I have always found you can campaign on anything you like but nothing is more effective than communism … If he’s a Labor man, he’s a socialist and a very dangerous man.’

‘He appealed to a very uneducated base.’

‘Phillip Adams nailed it when he compared him to politicians like Reagan. He called them ‘grotesque garden gnomes’, their visions as limited as their vocabularies, who are seen as colossi by their deluded followers. The louder we laugh at them, the more powerful they become. The more improbable their careers, the more certain their ascendancy.’

‘All based on intimidation. You can’t challenge them. All carried out through secrecy’, I said.

‘Repression feeds on secrecy. The state of secrecy overawes people. This reached its height in Queensland when they banned street gatherings. No more than three could march together and only with police permission. They refused this to groups who wanted to protest against uranium mining and other contentious issues.’

‘Some would say as you’re from N.S.W. you were interfering in the affairs of another state. Without so much as a by your leave.’

‘I’m an Australian and I don’t need permission to defend its laws. Laws be they just or unjust that apply to one of us, apply to all of us. And the struggle against these laws when they are unjust is the struggle of all.’

‘I remember hearing Bjelke Petersen questioning the relevance of human rights: ‘What’s the ordinary man in the street got to do with it?’

‘His street is a narrow dead end. I cannot sit by in Sydney and not be concerned about what happens in Brisbane. To paraphrase Dr. King, all communities are inter-related, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly.’

‘You were arrested on one of these illegal Queensland marches, weren’t you?’ I asked.

‘The Bjelke Peterson regime was giving us a small taste of what could happen in the future. Such forces of tyranny want people to go soft, to go quietly when asked, to keep things out of the media.’

The Hillbilly Dictator saw no role for the media in making government accountable, did he?’

‘He told the Australian Financial Review whilst in office: ‘The greatest thing that could happen to the state and the nation is when we get rid of the media. Then we would live in peace and tranquillity and no one would know anything.’

Bjelke Petersen said what happened there is nobody’s business but their own. This allows them to consolidate their position. I saw first hand the brutality that the Japanese soldiers inflicted on our troops. The sadism and vindictive manner that fascism brings out in people.

I saw this amongst the Queensland police. Me and sixty six others were jammed into a small cell like battery hens for seven hours.

When I put to the policeman in charge my queries as to the ethics of this, he indicated in his master’s voice that these queries were unwelcome. ‘Don’t bother asking for a bigger one. You won’t get one.’

I asked him if we had the right to have these conditions inspected.’

‘I can guess his response.’

‘The same catchphrase used by Joh, ’Don’t you worry about that’.’

‘You’ve been arrested more than once protesting. Why did you choose—‘

‘–that form of civil disobedience?’

‘Well, first of all, it encourages others to become involved, and it stops people from seeing you and distinguishing you as anything other than part of a broader movement. Sometimes you just do it because no one else will. Sometimes you do it because many others will. I think it’s important, because you bring energy to the community. Everywhere I go, people tell me, “Thank you.” So, there is a—there is a connection with a broader movement.’

‘What was your response to the coup against your government?’ I asked.

‘I felt that the proper response was a mass based action by the people. I backed calls for a national strike and demonstrations that would have made it impossible for anyone to think things were back to normal. We needed to make it clear such an act was opposed.’

‘If only that had happened,’ I said.

‘Alas everyone went quietly and anonymously to the ballot box to a time and tune decided by the coup’s engineers. This allowed the national commentariat to focus on accusing our administration of economic incompetence while ignoring the central issue of the democratic process.’

Before I left Tom’s home, I needed to go to the loo.

‘Never mind about flushing it’ he said. We have to reduce water consumption in every little way.’

‘To flush or not to flush. That is the question.’ I said, reminding him of the turn of events in government priorities. He was Minister for Urban and Regional Development in the first flush of the Whitlam government.

A task force headed by Dr. Coombs had recommended Tom’s department provide such basic services and amenities as sewerage facilities to the outer edges of the sprawling cities.

Replying to my rhetoric, Tom quoted the compliment of another Labor polly: “It was said of Caesar Augustus that he found Rome brick and left it marble. It will be said of Gough Whitlam that he found the outer suburbs of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane unsewered, and left them fully flushed.”

‘In this effluent society a lot of water has gone down the gurgler since, a flow that has to go.’

‘Gough had epic visions – national, international and, some believe, interplanetary, but they had their origins in a firmly grounded policy of improving the quality of life: he began with the outhouse, and reached for the sky.’

On hearing in early 2015 that Tom had been admitted to St. Luke’s Hospital in Roslyn Gardens, I asked his wife Christine for his whereabouts there. ‘He’s in room 1 of the second floor of Lulworth House, Allan.

‘When I arrived at the facility where Gough had spent his last days, Tom’s nurse Anne, told me ‘I’m afraid you’re too late, he’s sinking fast. Only family are allowed to see him now? Do you have any message for him? ’

I asked her to pass on my wishes to him and to tell him I’d be pursuing his vision to the best of my ability.